Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna.

For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about. The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

For all the sources mentioned in this video, don’t forget to check out our newsletter; the link is in the description.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Why is cement demand so strong?

Today, I’ll start by talking about cement. UltraTech’s results came out last week, and the management sounded extremely bullish about the economy. I wanted to understand why. What I found was a larger story about public infrastructure and private capex — and the gap between them.

Let me start with what UltraTech’s CFO, Atul Daga, said on the earnings call:

“Let me get to the core topic for discussion: demand. That is the most important aspect of our business. Everything else becomes secondary and falls in line.”

For the next several minutes, he proceeded to lay out an exhaustive, region-by-region catalogue of infrastructure projects across India. Punjab is spending Rs 16,000 crores on road development. Delhi Metro is announcing new corridors worth Rs 12,000 crores. And, the list went on.

One analyst joked that it sounded like a Union Budget speech.

But he wasn’t just listing projects for effect. He was making a specific argument about what these projects mean for cement demand. Elevated metros for example require 11,000 metric tons per kilometer. So, when you read that a city is adding 80 kilometers of elevated metro track, that’s potentially 880,000 tons of cement.

And he was explicit about where this demand is coming from:

“As we see the progress, government’s focus on infrastructure is translating into a robust pipeline of new projects nationwide, with several marquee investments announced across every region, translating into solid demand.”

Government’s focus on infrastructure. Remember this point. I’ll come back to it.

See, if UltraTech is seeing the demand picture from the cement side, JSW Steel is seeing it from the side of steel — a material just as important to infrastructure. And what JSW Steel described in their latest results was similar. When asked which sectors would lead this growth, management’s response echoed UltraTech’s thesis:

“We are seeing growth across sectors in the India story. This includes construction, infrastructure, and commercial real estate. We are seeing strong growth in industrial sectors and, post-GST, in consumption sectors like automotive and appliances. Another major area is renewable energy.”

JSW Steel also provided a useful piece of context that explains why October and November were weak for both cement and steel:

“Central government capex was low in October and November but is up 28% from April to November due to a strong H1 performance. The annual capex target appears to be on track.”

Government spending was front-loaded in the first half of the fiscal year, then slowed in October-November. When government projects paused, contractors stopped ordering materials, demand softened, and prices fell. But with the full-year capex target still on track, both companies expect a strong Q4 as spending catches up.

So far, this is a straightforward story. India’s two largest building materials companies are seeing strong demand, driven by government infrastructure spending. Both are confident about the future. Both are investing heavily to capture it.

However, when it comes to private capex, the confidence isn’t as strong as for infrastructure or real estate. Now, JSW Steel seems to indicate otherwise when they said:

“Conditions for private capex are increasingly conducive, supported by healthy balance sheets, the RBI’s recent rate cuts, and lower inflation.”

Now, conditions may be conducive. But is private capex actually picking up?

Before I answer that, let me explain why private capex matters a lot.

See, there’s a meaningful difference between an economy powered by government spending and one powered by private investment. When the government builds a highway, it creates demand for cement and steel and labor. But once the highway is built, that demand stops. The government has to keep announcing new projects, and keep borrowing to fund them, just to maintain the same level of activity.

Private investment works differently. When a company builds a new factory, it does so because it expects to sell products for years. That factory employs workers who earn steady wages. Those workers spend their wages on goods and services. That spending creates demand for other businesses. Those businesses then invest to meet that demand. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle that doesn’t require the government to keep borrowing.

Projects Today is a firm that tracks new investment announcements across India. Their CEO, Shashikant Hegde, highlighted his concerns on private capex to Business Standard. Private sector investment intentions have fallen for two consecutive quarters. Government investment announcements, meanwhile, rose sharply — the public sector’s share of new investment proposals climbed from under 30% to nearly 36% in just one quarter. The government is stepping in to compensate for private sector hesitancy.

He explained what’s happening:

“While domestic macro conditions remain supportive, often described as a Goldilocks phase with stable demand and manageable inflation, the willingness of private promoters to commit to large new capex may remain cautious in the near term. Global headwinds, including renewed tariff-related risks, geopolitical uncertainty and a softening export environment, are likely to keep risk appetite restrained and delay final investment decisions in private-led sectors.”

This is worth unpacking. By the textbook metrics, conditions look good — it’s a “Goldilocks” environment, not too hot, not too cold. But private companies aren’t investing anyway. They’re in wait-and-watch mode, uncertain about global trade, worried about geopolitical risks, and unconvinced that demand will be there when their new capacity comes online.

Remember JSW Steel’s comment that conditions for private capex are “increasingly conducive”? The Projects Today data suggests that conducive conditions aren’t translating into actual investment. The ability is there. The willingness isn’t.

This gap between conducive conditions and actual investment is not new. In fact, it has persisted for over a decade.

We wrote about this a few months ago.

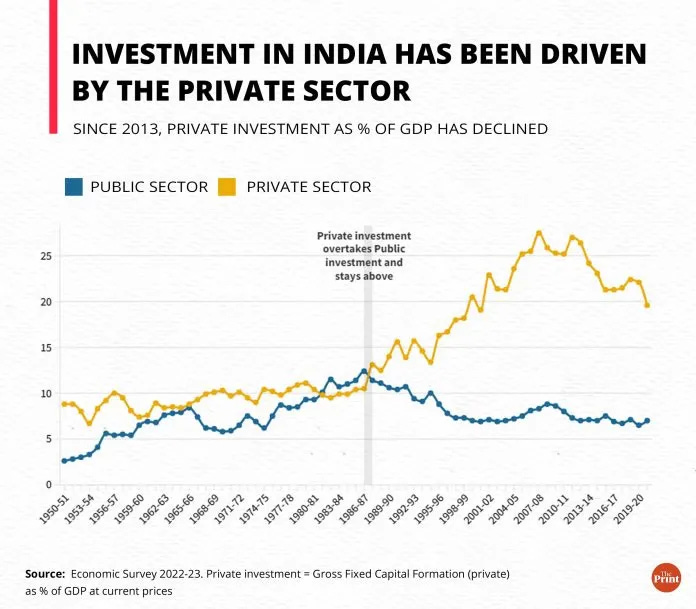

Private investment as a share of GDP peaked at around 27% in 2007-08, during India’s pre-financial crisis boom. Even after the global crisis hit, it recovered to about 27% by 2011-12. But since then, it has been on a steady decline — sliding to around 21% by 2015-16 and hovering there ever since.

The government has tried everything to revive it. After the NPA crisis that peaked in 2018, it cleaned up bank balance sheets and recapitalized public sector banks, hoping that freely flowing credit would unlock investment. It didn’t. In 2019, it slashed corporate tax rates — one of the steepest cuts in India’s history — hoping that higher profits would translate into more investment. They didn’t. It launched Production-Linked Incentive schemes to directly subsidize investment in targeted sectors. And when none of that worked, it ramped up public capex to historic levels, hoping that government spending would eventually “crowd in” private investment.

The result?

The private sector’s share of total fixed investment has actually shrunk — from over 40% in 2015-16 to just 33% in 2023-24. Not only has overall investment as a share of GDP declined, but the private sector’s slice of that shrinking pie has gotten smaller too.

The problem, as we noted in that piece, was never liquidity or incentives. It was demand and confidence. Companies invest when they believe customers will be there to buy what they produce. If they’re not convinced that demand will materialize, no amount of tax cuts or cheap credit will get them to build new factories.

Writing in the Financial Times earlier this month, Ruchir Sharma put it bluntly:

“It is no coincidence that domestic private investment in India has also been anaemic over the past decade, held back by the same regulatory maze and overzealous bureaucracy that foreigners complain about. And boosting investment, both domestic and foreign, is the key to creating jobs and stemming the exodus.”

These aren’t problems that government infrastructure spending can solve. You can build all the highways you want, but if companies don’t trust that the rules of the game will remain stable, they won’t invest.

None of this means UltraTech and JSW Steel are wrong about what they’re seeing.

But the composition of that demand matters. When Ultratech lists dozens of government infrastructure projects and says demand is everything, he’s describing an economy where the government is doing the heavy lifting. When JSW Steel says conditions for private capex are conducive, but the data shows private investment falling, that’s telling you something about the sustainability of this growth.

The infrastructure wave is real. But for it to translate into durable, self-sustaining growth, private investment has to follow which hasn’t happened yet.

And governments, unlike private companies, eventually run out of room to borrow.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Private capex is stagnant because the private capital knows what the the literal public does not want to know rather not even to acknowledge that the capacity will not be utilised if it’s built because the purchasing power and the per capita income has not grown in a decade.

Forget new capacities old capacities built a decade ago are not being utilised at their potential.

Risk of starting late.... we need futuristic companies like in USA or China who can think ahead of time