Why is global waste trade going down?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why is global waste trade going down?

A world in need of better jobs

Why is global waste trade going down?

We talk a lot about trade at The Daily Brief. We talk about tariffs and industrial policies, sometimes both, that quietly block trade. We talk about free trade deals that try to keep it flowing. We love talking about how trade touches the things we use every day.

But there’s one corner of global trade we’ve ignored: trash.

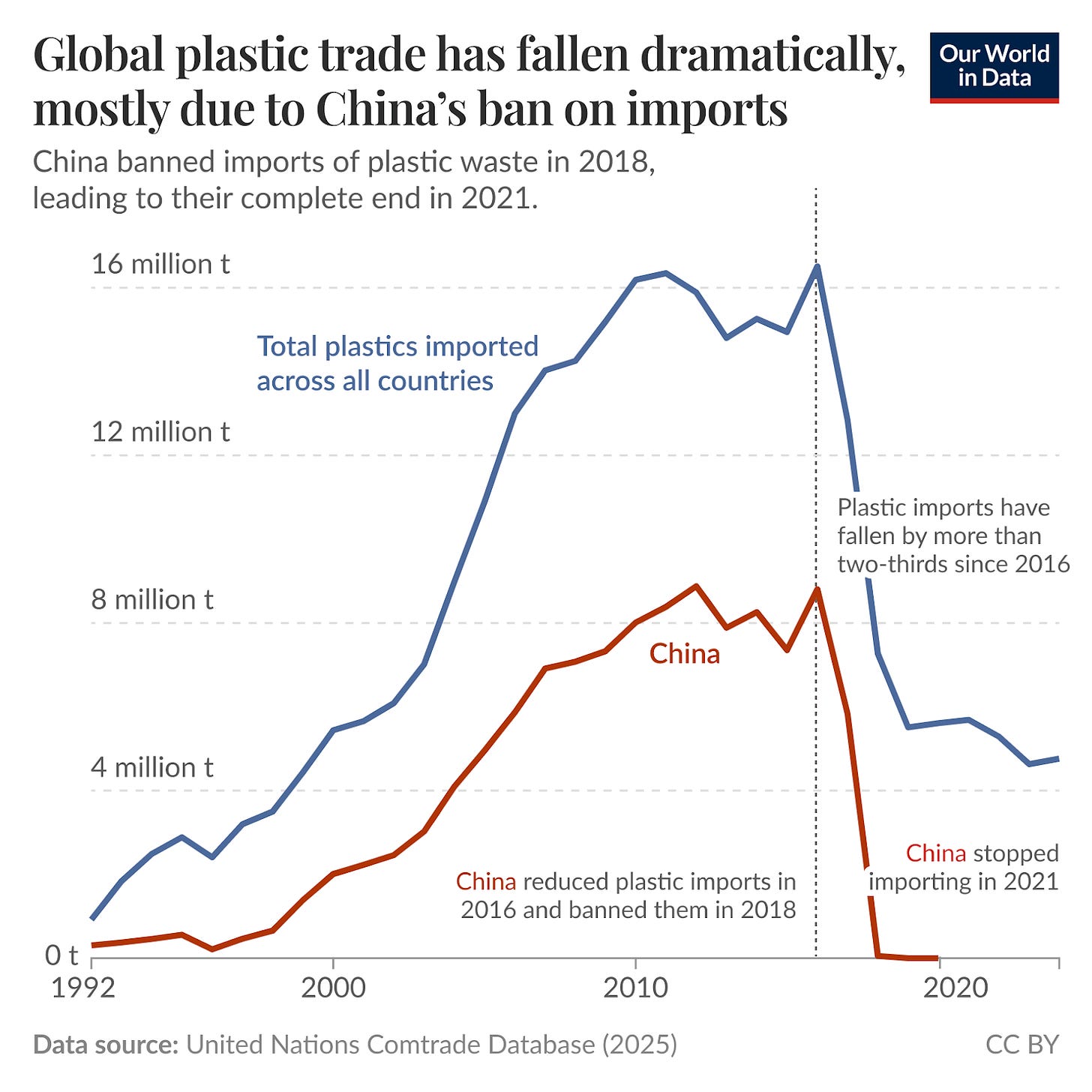

For years, there was a thriving industry that moved literal waste across borders. Then, early this decade, something broke. Our World in Data shows global plastic waste trade falling sharply — from about 12.4 million tonnes in 2014 to 5.8 million tonnes in 2023. That drop caught our attention.

How do we read this? Is this real environmental progress — with countries learning to handle their own waste better? Are countries learning to turn it into useful raw material for their industries? Or is this yet another industry done in by regulation?

To answer that, we need to rewind to the original logic of how this system worked.

Why trade trash?

Most people hear “waste trade” and picture rich countries simply dumping garbage on poorer ones. That does happen, no question. But there are layers to dig through.

Fundamentally, this is a story about basic industrial economics. The global waste trade existed because it solved real cost problems for both sides. For years, buyers and sellers both benefited from this — it made economic sense.

See, “trash” is not one thing. You might discard all sorts of things into your trash bin — used plastic bottles, food waste, electronics, metallic objects, corrugated paper, and so on. To you, they all have the same worth — zero. Markets, however, see them differently. Some of these are simply contaminant-heavy liabilities. A soiled paper plate, for instance, really is worth nothing.

Some things, though, are valuable industrial inputs. Take aluminum. Making it from recycled scrap uses about 95% less energy than making it from scratch. It’s incredibly valuable.

For decades, this created room for a simple arbitrage. Rich countries produced huge volumes of mixed waste. Sorting that trash was expensive, because it carried high labour and compliance costs. But putting it out of sight was politically inconvenient as well. Landfills and incineration were politically unpopular. Exporting that trash, meanwhile, was a convenient pressure valve. Even after paying for shipping and handling, it was cheaper to send waste abroad than to clean it up domestically.

Meanwhile, in many middle-income manufacturing hubs, labour was cheap. It was feasible to put people at work, sorting and processing that trash. And then, it could become cheap feedstock for their factories — often competitive with or cheaper than virgin raw materials. As the saying goes: one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

This was the heart of global trash trade.

Historically, China was the giant node in this system. By 2016, it handled more than half of globally traded plastic waste. That kind of concentration shaped global behavior: if China could absorb the volume, exporters could make their trash disappear, even when their own waste systems were weak. And for China — a country racing to become the factory of the world — this “foreign garbage” was a cheap and steady supply of plastics, metals, and paper for its factories. It would all become the stuff that the West would happily buy.

Clean veneer; messy reality

The trash trade allowed each side to tell a plausible success story. Exporters could claim to send material for “recycling”, without much effort. Global brands could market their “recyclable” packaging, as feeding a circular economy. Importing countries, meanwhile, could claim to create jobs and extract value from secondary raw material.

In many cases, that story was true. But it lived alongside a messier reality.

Start with contamination. A lot of so-called “recyclable” waste is mixed with food scraps, dirt, labels, glue, and the like. Some materials, like multilayer plastics, simply can’t be recycled. The higher that contamination is, the less usable a shipment becomes. There’s only so much contamination one can deal with. If recovery rates are too low, or processing costs too high, the underlying economics breaks. “Recyclable” waste just becomes waste.

Some trash is nobody’s treasure.

A big problem with the trash trade was that often, importers found the waste too contaminated to work with. Many of them had solid rules, on paper, about contamination rates. But they had little capacity to enforce those rules — with limited port inspections, poor tracking systems, and patchy local monitoring. Low-quality shipments would routinely still slip through.

So what would importers do? Well, if the waste they imported wasn’t fit to work with, they would let it leak into informal channels — open burning, crude melting, unsafe washing, or just dumping. Commercially, this cost them next to nothing. But those costs were borne by the entire country, in the form of pollution, along with health risks for workers. These trades were officially logged as “recycling,” but in reality, they were just somebody else’s problem.

So, what looked like a nice “circular economy” was much darker. It wasn’t always pure dumping, but often, it wasn’t “green” either. What happened varied widely, depending on the type of waste, how strict the importing country was, and how well rules were enforced.

Passing the (trash) parcel

In 2018, China began cracking down on trash imports, in a series of measures commonly grouped under “National Sword”. Too much of its trash was contaminated, and that was adding to its air and water pollution problems. So, it banned 24 categories of solid waste. It also stopped importing plastic waste with a contamination level of above 0.05%, which was significantly lower than the 10% that it had previously allowed.

Until this point, China was taking in the bulk of the world’s recyclables. That door was suddenly shut.

But the flows of trash didn’t disappear. They began moving elsewhere.

Trash shipments first began re-routing to Southeast Asia. Countries like Malaysia and Thailand saw plastic waste imports jump 273% and 640% respectively after the ban. Soon, they too were overwhelmed, and moved to tighten their own import rules. India briefly became a potential destination, but we too banned the import of plastic waste in 2019, although we actually relaxed it a bit in 2022.

Then, Turkey emerged as a key destination for European Union waste, receiving nearly half of all EU plastic waste exports by 2020. But even there, restrictions followed.

The world’s trash trade, in essence, relied on one giant buyer. Once that buyer stepped back, everything began to falter.

And then came a second institutional break: the Basel Convention’s plastic waste amendments, starting from January 2021.

The Basel Convention, in a sense, is the global rulebook for shipping trash. It’s a treaty signed by over 190 countries to control how hazardous waste moves across borders. The new amendments created clearer categories for plastic waste and made it harder to pass off dirty material as recyclable. They also expanded what’s called the “Prior Informed Consent” process: if a country wanted to export mixed or contaminated plastic, it had to notify the receiving country before shipment. It was only if the importer gave their written consent could the shipment leave the country.

That changed the math. If the trash trade were a matter of looking the other way when contiminated shipments came in, that was one thing. But few countries could commit, on paper, to take complete waste into their borders.

And now, there’s a third break coming. The EU has put out revised waste-shipment rules, which include a ban on plastic waste exports to non-OECD countries starting from November 2026. That will likely push even more regionalization, and force capacity to adjust again.

In essence, the trash trade was hit by multiple shocks, one after the other. That’s why it is increasingly infeasible.

Is falling waste trade good news?

At first glance, this sounds like… progress. If trade volumes are down, maybe countries will finally handle their own waste? That would be a nice end to this story.

But that conclusion deserves a pause.

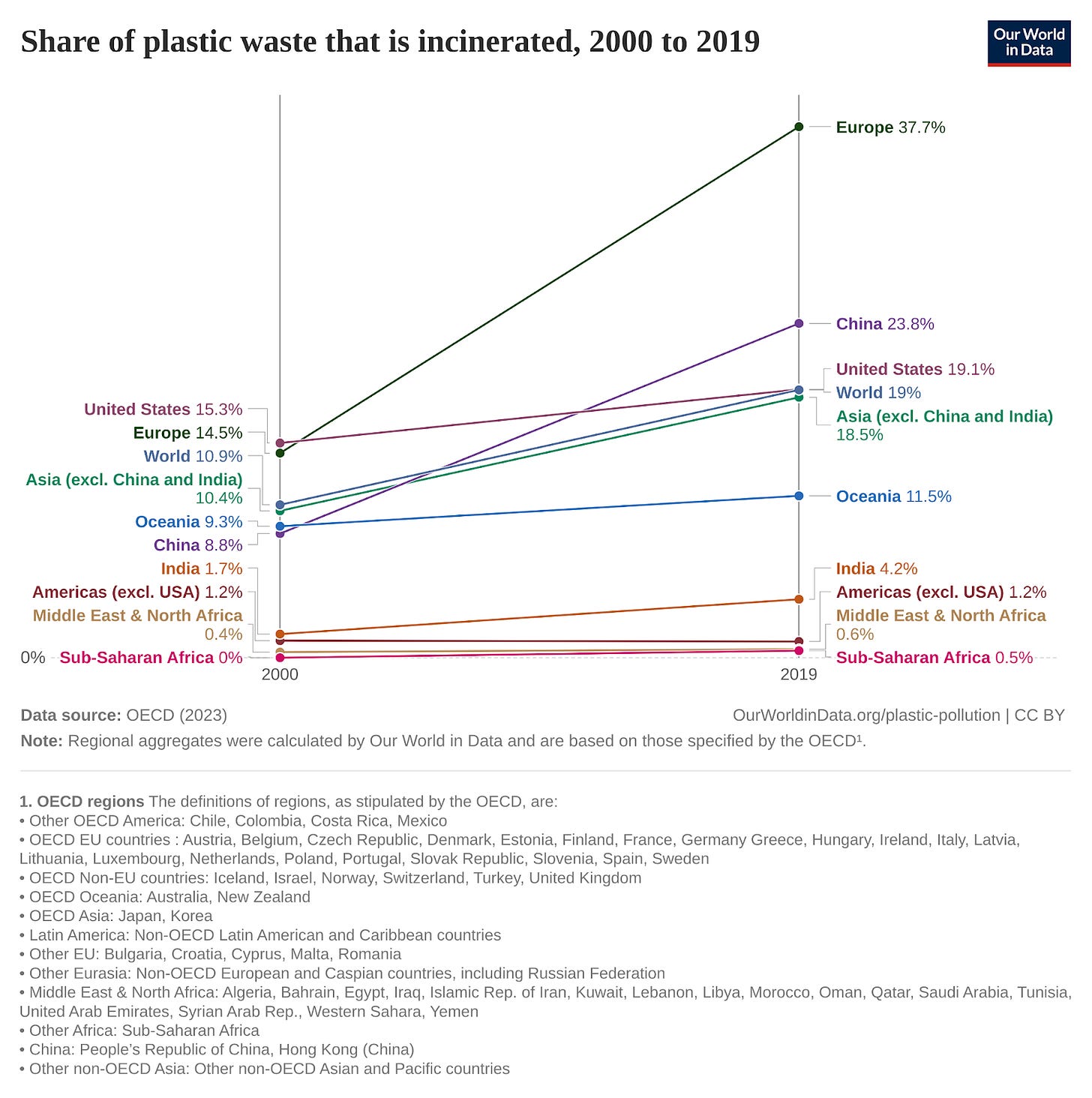

Less trade doesn’t always mean better recycling. Often, it has meant more incineration and more landfilling. OECD data shows that recycling rates in “mature” systems like Germany, the US, and Japan have largely stalled. In 2000, the average recycling rate among the top 10 OECD recyclers was 27%. By 2018, it had only edged up to 32%. That’s a marginal movement over nearly two decades.

Increasingly, a chunk of the excess waste has gone to “Waste-to-Energy” plants: where trash is burnt — like in poorer parts of the world — but that heat is used to make energy. In European OECD countries, incineration rates rose from 14.5% in 2000 to 37.7% in 2019.

Meanwhile, the headline that “trade is down” may not be clean either. Data can be messy. A lot of the supposed “progress” is clouded by gaps in reporting.

In fact, some material just started moving under different labels — like cleaner scrap, “fuel,” used goods, or straight-up mislabelled shipments. For instance, you can ship plastics “converted into fuel” under a different Harmonized System (HS) Code, not the usual plastic-waste code. On paper, then, its no longer “plastic waste trade” —- even if it’s the same material wearing a different badge.

Scrap metal: the opposite story

While plastic waste is getting boxed out, however, scrap metal is moving in the opposite direction. It’s starting to look like a strategic climate asset.

You can see it in trade flows. In 2023, Turkey imported 18.67 million tonnes of ferrous scrap. India was next at 9.81 million tonnes. Then came Vietnam, Italy, Korea and others. In a decarbonizing world, scrap is fuel for “green” production.

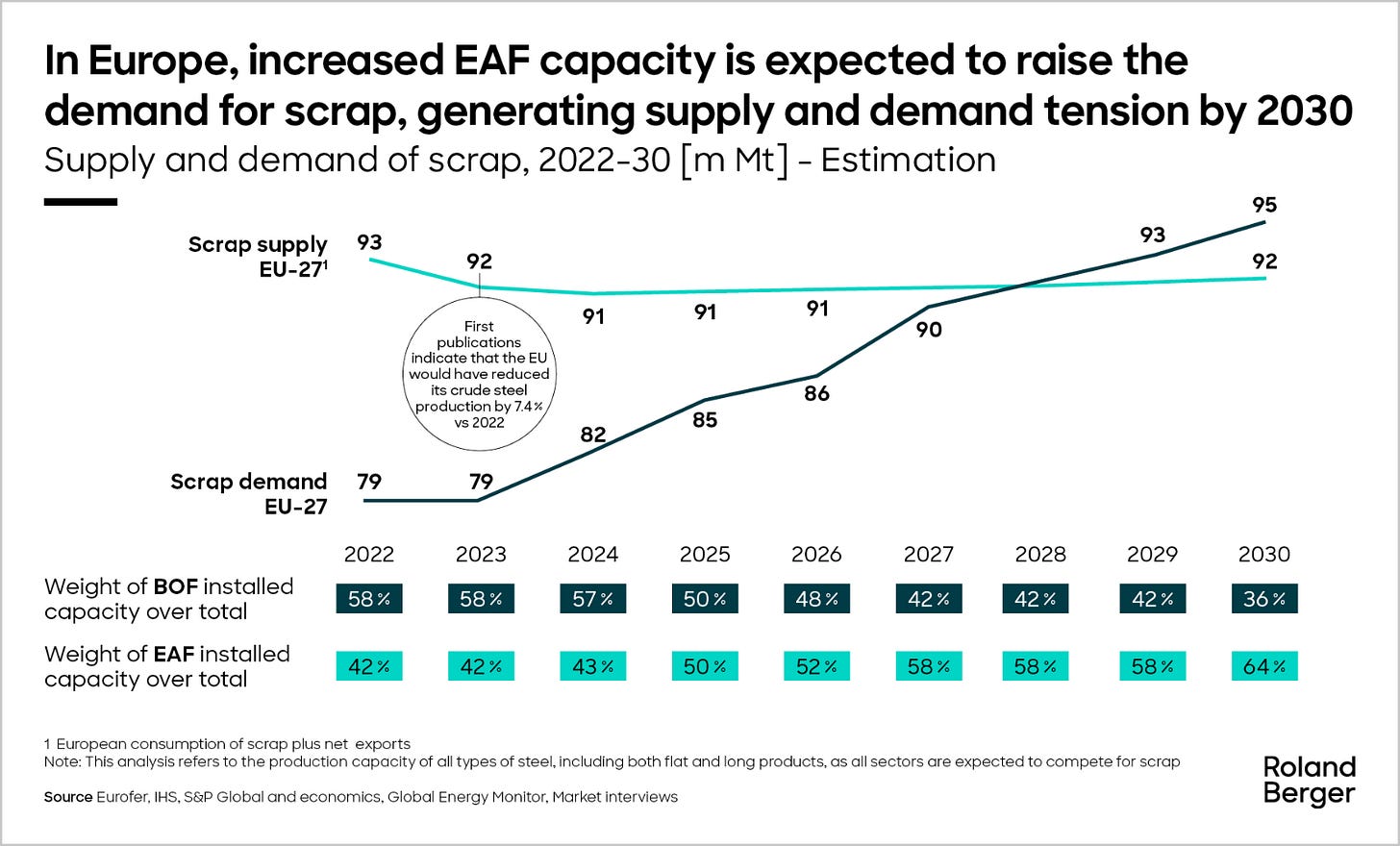

Take steel. Traditional blast furnaces burn coal and emit heavily. Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs), which largely run on scrap, are far less carbon-intensive. In Europe, EAF’s share of steel production has risen from 30% in 1990 to 45% today. That only works if scrap is available.

But there’s a problem: getting your hands on that much scrap is hard, especially if you’re exporting trash. And so, countries are bringing in export controls. In the US, for instance, the Aluminum Association has pushed for a ban on exports of used beverage cans, to support domestic manufacturing. The pitch is simple: recycling aluminum saves massive amounts of energy. Why ship that advantage abroad?

In Europe, similarly, the proposed Metal Action Plan includes the possibility of restricting recycled steel exports to ensure local EAF plants have enough high-quality feedstock.

We may be heading into a new kind of trade fight. Not over oil or rare earths — but over scrap.

A world in need of better jobs

Last month, the International Labour Organisation released the 2026 version of its Employment and Social Trends report — a sweeping look at the entire world’s jobs landscape.

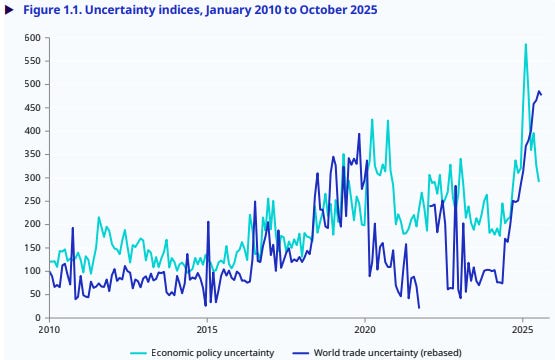

At the aggregate level, its findings seem heartening. The world’s economic activity is growing. Its labour markets are resilient. Unemployment is low. If one feared a crisis, given all the trade-related sabre-rattling of 2025, things are reassuringly normal. And yet, the ILO’s tone is one of alarm, not reassurance. The stability at the surface, the report argues, is concealing a deterioration underneath.

This is the central paradox that the report unpacks.

The paradox of resilience

There are roughly 186 million people, across the world, that are currently unemployed. That might seem like a lot, but with an unemployment rate under 5%, it’s historically low.

That should be good news. But it’s worth understanding what it means.

“Unemployment” is a tricky term — it looks at the number of people without a job that are actively seeking work. For every such person, however, there might be others — those who have given up on ever finding a job, or those who have other responsibilities, like parenthood, who can’t find a job that they can balance alongside.

And so, the ILO looks at another, fuller measure — what it calls the “jobs gap”. This includes people who want to work, in general, but aren’t actively seeking a job. That figure is over 400 million. More than one in ten people who are willing to work don’t have any.

That gap is where our story begins.

The broken elevator

Over the last few decades, we ran on a comforting economic assumption: that growth lifts all boats. As economies expanded, the theory went, their informal sectors would shrink. Workers would graduate from precarious, badly-paid work into the formal economy. The elevator of development, in other words, would keep moving.

The ILO’s report, however, suggests that the elevator has broken down.

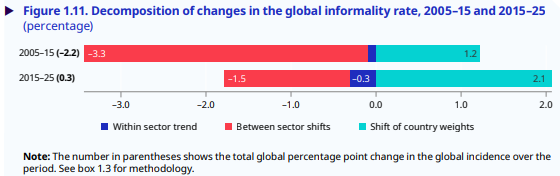

After a long period of decline, the global rate of informality — the share of workers in unprotected, unregulated jobs — is rising. Consider this: between 2005 and 2015, global informality declined by 2.2%, even though the period that included the Global Financial Crisis. Over the last decade, however, that progress not only stalled; it reversed. Informality is now inching up, and might reach 2.1 billion workers by 2026.

This is, in part, a matter of “composition effects”. Countries with very high levels of informality, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, also have the world’s fastest-growing populations. Even if most countries are making slow progress, these growing populations pull the world average down.

But there’s a deeper problem here: unlike growing economies of the past, these growing populations are stuck in informality. They aren’t seeing what economists call a “structural transformation“ — or the process by which workers go from low-productivity to high-productivity sectors. In fact, the rate of this transformation has slowed to roughly half its speed in the previous decade. A generation ago, many countries were making rapid leaps from agrarian poverty into industrial modernity. That engine of development is now sputtering.

This has terrible consequences for those who can least afford it. Because increasingly, work alone doesn’t guarantee a better life. In 2025, 284 million workers globally lived in extreme poverty — earning less than $3 a day — despite having jobs. In low-income countries, the share of workers in both extreme and moderate poverty actually increased between 2015 and 2025.

Two worlds, two dead ends

You can think of the world as being stuck in two tracks, both of which face different employment problems. Neither, sadly, has a clear path out.

Waithood: The paradox of being too educated

The lower-income parts of the world face what the report calls “waithood.”

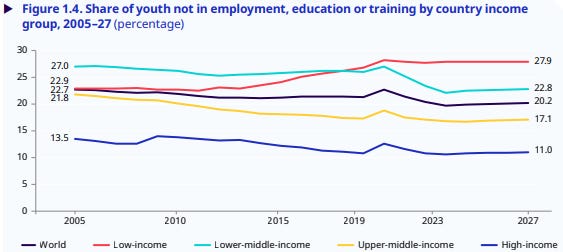

In an ideal world, education would lead to better employment. Increasingly, however, in low- and middle-income countries, the opposite is often true, at least for young people. Youth with advanced education in these countries face unemployment rates of roughly 36.6%, compared to 11.3% for the youth average overall.

In these countries, educated young people hold out for formal-sector or government jobs — which offer stability, legal protections, and a living wage. They can afford to wait, because their families can support them in the interim. Meanwhile, young people with less education cannot afford to wait; and so, they take whatever informal work is available. In that perverse sense, they are more “employed” — even if they’re in low quality jobs.

This creates a “NEET crisis” — in these countries, a surprisingly large number of young people are “neither employed, nor in education or training”. A university degree can, paradoxically, make you more likely to fall into that category.

The way out, ideally, should lie in an upgradation of these economies — the structural transformation we mentioned earlier. But that seems increasingly difficult.

This is, in part, a matter of debt. To create better high quality jobs, countries need to invest in their economies. And for that, they need to borrow capital. Only, at this moment, debt servicing costs are at historic highs. At a moment like this, its only countries that can promise a good return on their debt are still borrowing heavily. That’s happening in the gulf region, for instance — where countries are borrowing heavily to diversify away from oil and build new industries. On the other hand, those that can’t — like much of Africa — are being forced into austerity.

Aging out: The rich world’s shrinking workforce

The higher-income world, meanwhile, has the opposite problem.

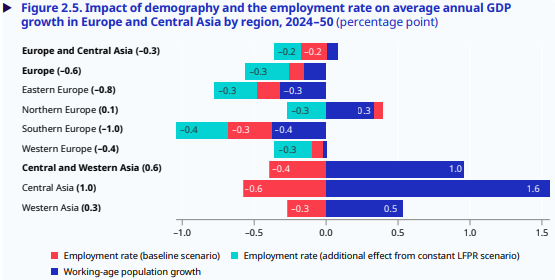

Its challenge isn’t too many young people without good jobs; it’s too few young people, period. These countries are seeing their populations age rapidly, and that is contracting their workforces. The workforces of these economies are contracting at around –0.1% a year — shaving roughly 0.2% per year off their growth rates.

And it is in this state that they’re entering a time of technological disruption.

Manufacturing is no longer an escape hatch

Most countries that escaped poverty, in recent years, had one playbook: manufacture for the rest of the world. Manufacturing jobs are unique, in that they absorb large numbers of low-skilled workers, promising them a decent livelihood. It isn’t hard for a farm hand to get a job on an assembly line — even as it pays much better.

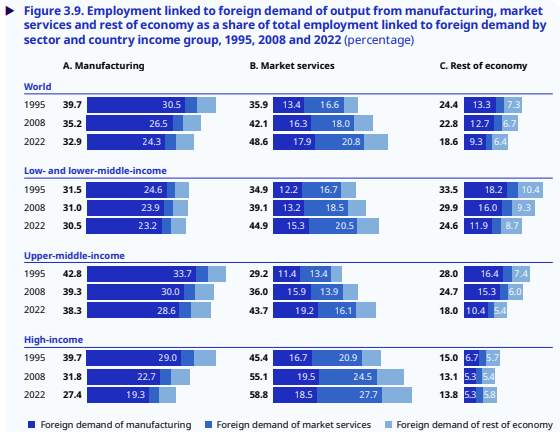

The best manufacturing jobs were all oriented to foreign markets. By and large, only the least competitive industries focused solely on their home markets. And these offer worse jobs — with more informality, worse pay, and worse working conditions. And so, to develop, poor countries would connect to global supply chains, and lean on their cheap labour for foreign exports. South Korea, Taiwan, China — all of them mastered this template.

Recently, however, two forces have dismantled this playbook.

One, in recent years, the world, led by the United States, has drawn away from foreign trade. As a result, the world’s manufacturing powerhouses — China and various East Asian countries — are facing severe headwinds. In fact, we may not even have seen the worst of it. Through much of last year, businesses tried to beat Trump’s tariff deadlines by “front-loading” their imports. That created a short-lived spike in demand. In the long term, things could become worse.

The same wave has also hit India. As the report notes, our part of the world has 6.3 million jobs that are directly linked to the market for exports to America, in industries like textiles.

But Trump did not begin this decline. The truth is, over the last few decades, manufacturing has increasingly been automated. The world can produce more goods with fewer workers. That might make it easier for us to make things, but it also reduces the sector’s job creation capacity.

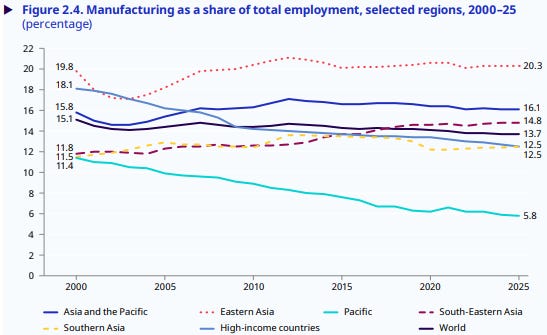

The decline is particularly visible in the world’s richest countries. There, the share of manufacturing jobs that cater to foreign demand has dropped dramatically — from roughly 40% to a little over 27% in the last three decades. In low- and middle-income countries, meanwhile, manufacturing makes up a relatively flat 30% of jobs catered to foreign trade. Manufacturing is still a part of these countries’ development playbooks, but the structural transformation — new people pouring into these jobs every year — has stalled.

Many manufacturing jobs are, now, indistinguishable from services jobs. Factories that once employed armies of assembly-line workers now run on robotics, sensors, and a small, technically skilled workforce — engaged in tasks like research, design or marketing.

Let’s say you set up a business selling cars to the world. Most jobs you offer, now, will have little to do with bolting or welding those cars together. Your workers will design those cars on computers, or analyse data on how your cars handle different conditions.

So, even if a country incentivises lots of factories, they might no longer create a lot of low-skilled employment. Instead, trade-oriented jobs increasingly lie in the services sector. These jobs, almost by definition, require the kind of education and skills that low-income workers don’t have. You can’t transition an agricultural worker into a data analyst in one step.

The AI Question

In 2026, it’s hard to talk about labour markets without looking at the elephant in the room: artificial intelligence.

As the ILO sees it, at this moment in time, artificial intelligence is a source of labour uncertainty. We do not know precisely what it will do. While it feels like a revolution, the productivity changes it brings aren’t visible in any large-scale data. At the moment, businesses are just trying to understand how AI will alter their operations. As the report argues, generative AI has “not yet fundamentally reshaped employment patterns”. From what we know, it doesn’t yet seem like entire occupations, at least, will disappear instantly.

But while businesses watch for what’s happening, they’re hesitant to hire and expand. As a result, even though AI hasn’t brought about a complete displacement of workers, it has cooled job market vacancies substantially.

There’s one cohort that’s become a “canary in the coalmine”: the highly-educated youth.

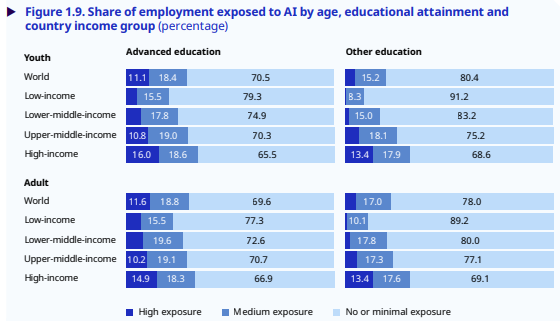

There used to be a traditional career ladder: young people would enter the workforce doing routine cognitive tasks, and would slowly move, from there, to more responsibility. These tasks, however — coding, drafting, data work etc. — is precisely what AI is best suited to replace. AI has, in fact, reversed the traditional advantage that people got from high education. Better educated youth are at a higher risk of displacement than their peers with less education.

There’s an extra complication: the parts of the economy that face the most disruption in the short term will also see the largest productivity boost over time. There is no clean safe harbour. Any part of the economy where jobs are relatively secure, at the moment, could well end up on the wrong side of a digital divide — with a risk of being left behind entirely as those AI-augmented sectors accelerate away.

An era of uncertainty

The picture that emerges from the ILO’s 2026 report is not one of crisis in the conventional sense. Unemployment remains relatively contained. Economies are, broadly, still functioning.

Behind that apparent stability, however, the assumptions we once held behind growth and employment are losing their grip. We’re no longer on a clean arc towards progress — the informal economy is growing; structural transformation has decelerated; the manufacturing playbook is faltering. And on top of all this, technology has added to the confusion.

This is a time of uncertainty. We aren’t in a crisis, but all bets are off.

Tidbits

Cochin Shipyard wins $360 million order for LNG container ships

Cochin Shipyard has bagged a $360 million contract from French shipping giant CMA CGM to build six LNG-powered container ships. This is the first time “Made in India” container ship orders have gone to an Indian shipyard. The first vessel will be delivered in 36 months, with the rest coming every six months after that.

Source: MintHUL to spend ₹2,000 crore to expand premium manufacturing

Hindustan Unilever will invest ₹2,000 crore over two years to expand production in premium beauty, personal care, and home care liquids. The company says it’s doubling down on “fewer, bigger bets” in fast-growing categories like skin care and hair care. A big focus will be automation and a more tech-enabled supply chain across multiple locations.

Source: Financial ExpressBangladesh blocks SpiceJet flights from using its airspace

Bangladesh has stopped SpiceJet from overflying its airspace due to unpaid navigation charges, forcing longer routes for flights to Northeast India. The detour adds around 30 minutes of flying time and increases fuel costs, hurting the already cash-strapped airline. SpiceJet says it’s in talks with Bangladeshi authorities to resolve the issue quickly.

Source: The Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Krishna.

We’re now on WhatsApp!

We’ve started a WhatsApp channel for The Daily Brief where we’ll share interesting soundbites from concalls, articles, and everything else we come across throughout the day. You’ll also get notified the moment a new video or article drops, so you can read or watch it right away. Here’s the link.

See you there!

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

You guys maybe need to publicise Sierra Energy’s FastOx gasifier here. This is essentially a repurposed blast furnace of the kind so common in the steelmaking industry, and can transform an incredible variety of waste streams into syngas and slag stone. The operator can choose what to turn that syngas into — electricity or hydrogen or synthetic fuels. Sierra has had a demo plant running at the US Army’s Fort Hunter Liggett training base for many years now.