Between industrial policy and trade imbalances

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Between industrial policy and trade imbalances

Breaking India’s corporate bond chakravyuh

Between industrial policy and trade imbalances

Industrial policy is back in fashion. Governments across the world are intervening in their economies with a vigor not seen in decades.

The US, for instance, has the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, pouring hundreds of billions into semiconductors and clean energy. China’s “Made in China 2025” programme has evolved into an even more aggressive push to dominate electric vehicles, batteries, and AI. Even India, with its Production Linked Incentive schemes, is firmly in the game.

But a question that doesn’t often get asked about these programmes is: what happens to the rest of the world when one country’s industrial policy succeeds?

A new paper by economists Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Andrea Ferrero, Luca Fornaro, and Martin Wolf tackles exactly this. They look at how national industrial policy reshapes not just the nation itself, but structurally distorts the entire global economy, while also shifting technological power between nations.

We covered a previous paper by Fornaro and Wolf on how tariffs are being used to chase technological hegemony. This new work goes deeper one level, analyzing how governments choose to re-industrialize.

A world of siloes

The first important thing to understand is that industrial policy alone doesn’t create global imbalances. A government can subsidize its semiconductor industry or its green energy sector all it wants. If domestic consumers spend enough to absorb the increased output, the rest of the world is largely unaffected.

In other words, as long as national demand keeps pace with national supply, all is fine.

The trouble starts with what the authors frame as an “unbalanced policy mix“. Here, the way a government chooses to boost production and install more factories is by ordering policy in such a way that people consume less themselves.

Governments can suppress demand in many ways. For instance, the state can keep interest rates on deposits artificially low. This, in turn, subsidizes businesses and infrastructure projects that need borrowings, at the expense of the common person’s bank deposit. Or, through tight fiscal policy, the government can also limit the issuing of government bonds where household savings can be invested.

As a whole, this results in people having little choice but to accept low interest rates. Broadly, this is called financial repression.

In the authors’ framework, the outcome of financial repression is that, at a national level, income gets shifted away from consumption. This raises savings, which get directed in favor of factories, infrastructure projects, and so on — but those investments aren’t enough to absorb all the savings. There are many debates regarding this framework, but we’ll save those for another day.

So now, you have excess savings, and not enough domestic safe assets to park these funds. In that case, the country often turns to foreign assets. This flood of funds into global markets pushes down interest rates worldwide. At the same time, since the host country keeps buying more foreign assets, there is sustained downward pressure on its exchange rate.

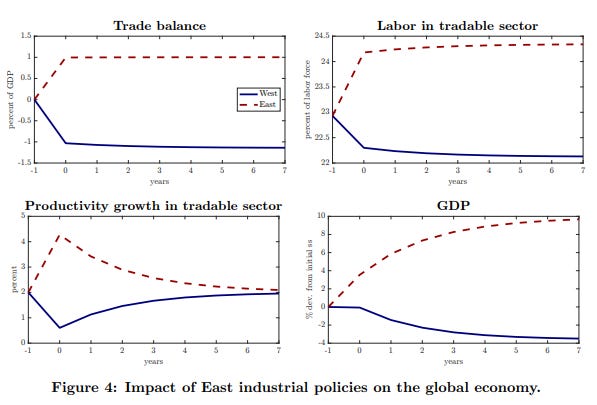

Most importantly, if the industrial policy succeeds, the host country begins producing massive volumes of goods, raising GDP. It might even achieve leadership in some technologies. However, since domestic demand is low, production often exceeds consumption.

In the short run, this looks great for the rest of the world. Lower interest rates mean cheaper borrowing, so other economies can finance consumption on easy terms. Cheap, subsidised goods flow in from the surplus country. Global consumers get inexpensive electronics, solar panels, and EVs. This effect is made even stronger by a relatively low exchange rate, which makes the host country’s exports more competitive.

But, as the paper says, this gift might just give way to a more painful period for the importing country.

The long-run trap

See, households in regions with large trade deficits — say, the US or Europe today — can import cheap tradeable goods from the surplus country. But they can’t import non-tradeable goods. You can’t import a house, a haircut, or a construction project. Those have to be produced locally.

So when cheap foreign capital floods in and interest rates fall, consumption booms — but it does so disproportionately in the non-tradeable sector. More money flows into real estate, construction, and local services. Resources migrate out of the tradeable sectors (like manufacturing) and into these domestic industries.

This is where the long-run damage happens.

In the paper’s framework, the tradeable sector is the engine of growth for any economy. It’s where the bulk of innovation and R&D happens. In the US, for instance, the manufacturing sector alone accounts for ~70% of total R&D spending, despite representing only about 10% of value added. When you account for high-tech services, like Big Tech, the tradeable sector is overwhelmingly where productivity gains come from.

As resources shift away from this sector and towards construction and services, firms have fewer incentives to innovate. The profits that reward successful innovation shrink as the tradeable sector contracts, and as a result, R&D investment also falls. The impact of reduced innovation on productivity takes time to materialise, so nobody notices the damage for a while.

The authors call this a “financial resource curse“. This is a deliberate comparison to the “natural resource curse”, where oil-rich countries often see their manufacturing sectors wither because they become too oil-dependent. Except here, it’s not oil, but cheap foreign capital causing the damage. This only gets strengthened by a foreign exchange rate that is structurally kept lower through the surplus country’s policies.

The endgame, as per the paper, is that the deficit country de-industrializes. Its innovation engine slows, and its productivity growth stagnates. The surplus country, meanwhile, sees its tradeable sector expand and its technological capabilities compound. The balance of technological leadership — who controls critical supply chains, who has bargaining power in global negotiations — shifts in its favour.

None of this means that a trade surplus or a deficit is inherently bad — countries can grow healthily even while running deficits. Nor does it mean that industrial policy is undesirable at any level.

But, what matters is the nature of the surplus or deficit. If one country achieves higher productivity while also causing imbalances, certain importing regions must also be absorbing those imbalances. This could be anything from less GDP, to more unemployment, etc. This is a yin-yang situation.

Textbook cases

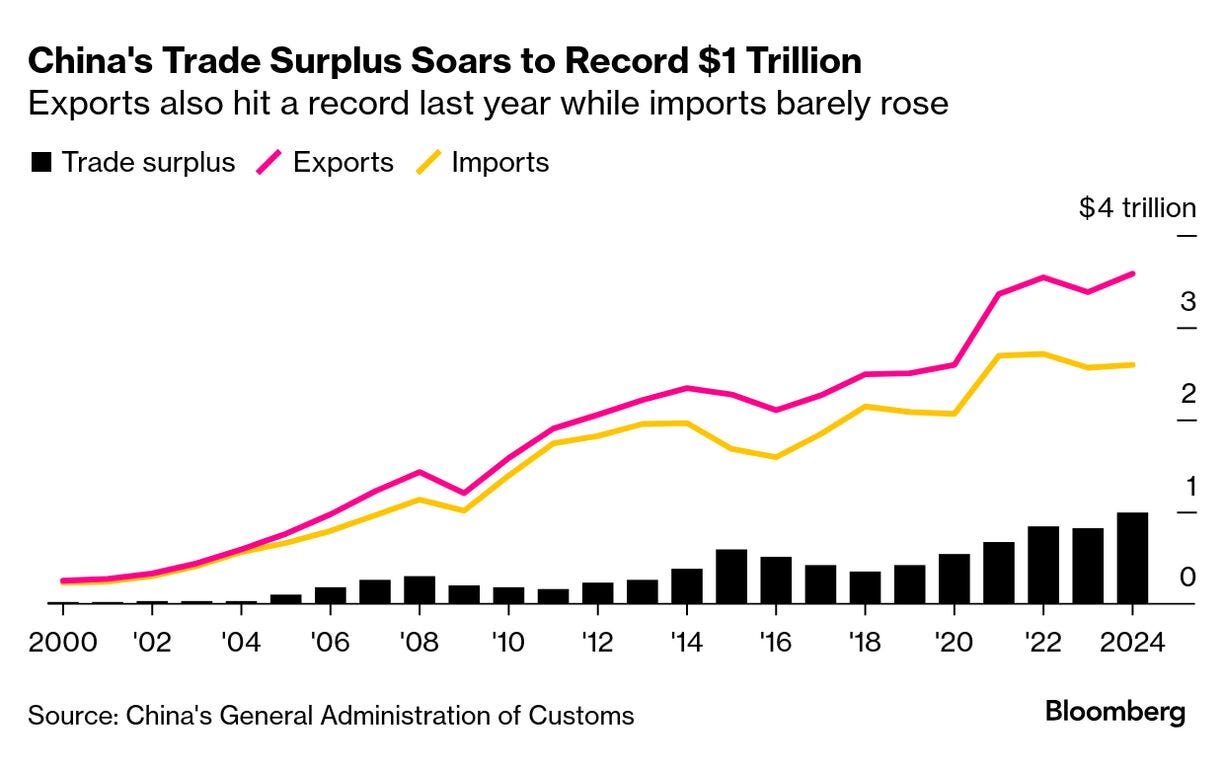

If all of this sounds familiar, it should. The authors hold China as the classic example of an unbalanced policy mix.

For decades, China’s growth has been driven by financial repression. The state has kept borrowing costs artificially low for manufacturers, which, in turn, constrained the income available to consumers. Wages have historically not kept pace with productivity gains — a deliberate transfer of wealth from households to the industrial sector. China’s excess savings regularly get directed towards buying US treasuries.

China runs a whopping trillion-dollar trade surplus, flooding the world with manufactured goods. Meanwhile its own consumers under-spend relative to what the economy produces — even if, in absolute terms, they consume a lot.

China is not the only example of this, though. In the late 20th century, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan followed similar policies, which were instrumental to their economic rise. Germany, too, shared some of these traits in their post-World War II rebuild.

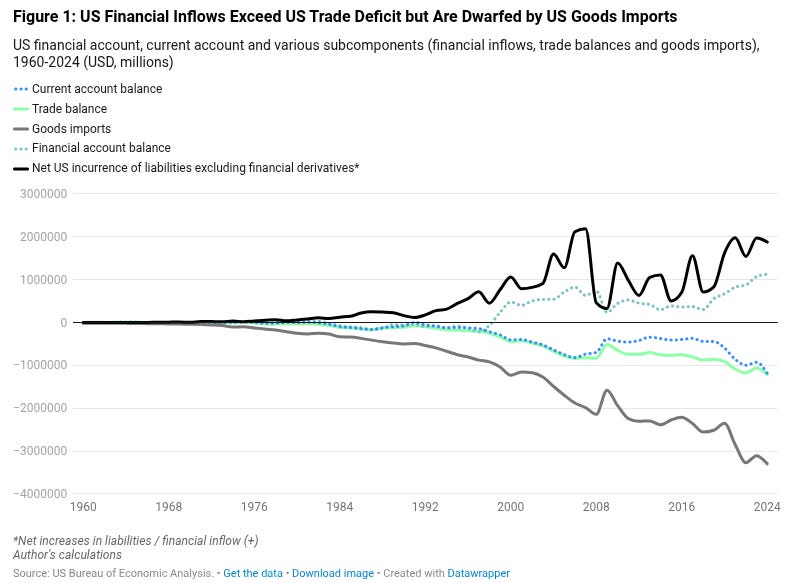

But it’s important to recognise the other side of this ledger, too. For every country that under-consumes, there must be someone who over-consumes.

That’s where Western countries, led primarily by the US, come in the story. The US runs persistent trade deficits while being financed by capital outflows as the largest recipient of FDI in the world.

Much of this global imbalance is as much the result of America’s own economic policy as it is of China’s — this is a topic for another time. Either way, while Western consumers enjoyed cheap goods, Western industry weakened.

This imbalance cannot be solved by one side alone. China suppressing consumption and the West absorbing the excess are two sides of the same coin. Rebalancing requires action on both ends.

What actually works?

So, what should countries on the receiving end of these imbalances do? The paper evaluates several options.

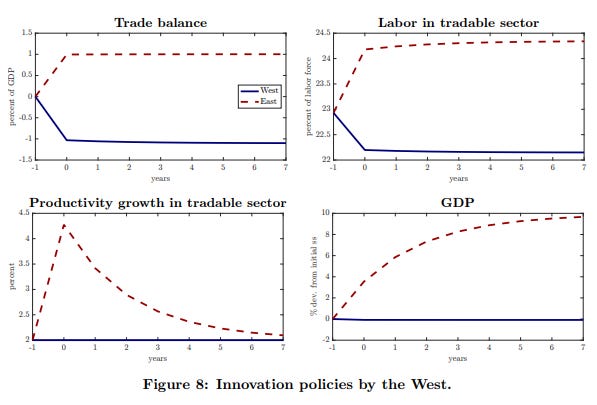

One such tool is innovation subsidies, and the logic behind them is simple. If the problem is that cheap foreign capital is flowing into low-productivity sectors like construction, redirect it. By subsidising innovation in manufacturing, the government makes those sectors more lucrative to compete that capital away from non-tradeables. Instead of cheap credit fuelling a housing boom, it finances productivity-enhancing research.

The paper’s simulations show that with well-targeted innovation policies, a deficit country can actually benefit from the trade surplus of the other — enjoying cheap goods and cheap credit while maintaining its own innovation engine. A win-win is indeed possible.

But there’s a crucial caveat. These innovation subsidies don’t address the underlying trade deficit or excess capital inflow — they just redirect it. In fact, economist Michael Pettis, who the authors often reference in their paper, says that subsidies will only help a few sectors. As long as the US trade deficit remains as big as it is, he says that US manufacturing will mathematically be limited.

Another tool the authors address is trade tariffs, which they call ineffective for fixing global imbalances. The paper is blunt about this: tariffs might lower imports, but they also cause the currency to appreciate, which hurts exports by roughly the same amount. The net effect on the trade balance is negligible.

What you get instead are distortions in the economy — like higher prices and misallocated resources — without solving for what actually drives the deficit. Tariffs are a blunt instrument for what is fundamentally a macroeconomic problem.

On similar lines, the authors advise against copying the other side’s playbook. If the West responds to China’s unbalanced industrial policy with its own such policy, the result could be catastrophic. Both sides would be reducing global demand simultaneously. The paper warns this could push the world into secular stagnation. Here, everybody suffers from chronic weak demand, persistent unemployment, and lower growth.

To a large degree, we’re already seeing this play out with the US and China’s trade war today. In a race to the bottom, countries compete to export their economic problems to the world rather than cooperate to grow together.

The hardest answer

The paper’s preferred solution is multilateral coordination, where the countries work together and use industrial policy in a controlled fashion. This would, in theory, reduce global imbalances without crushing global demand.

In practice, though, it looks tougher with each passing day. The two largest economies view each other with suspicion bordering on hostility. Asking China to restructure its growth model to consume more is asking it to give up the very strategy that has fuelled its rise. Asking the US to consume less might involve getting them to accept a lower standard of living in the short term. Both of those things look difficult even without the enmity between them.

And so, we’re left with a fragmented world, each country pursuing its own industrial strategy, each trying to gain an edge over the other, and the global economy absorbing the scraps.

Breaking India’s corporate bond chakravyuh

A few days ago, we mapped out the many structural problems that keep India’s corporate bond market underpowered.

It’s a bleak picture. Issuing debt publicly is expensive and cumbersome. The investor base is narrow, with large buyers either mandated or nudged into buying government paper instead. And once you do buy a bond, there’s barely a market to sell it in. Every link in the chain is compromised.

These problems can’t all be solved at once. All you can do is chip away at them.

Last week, the RBI unleashed its most significant attempt at doing so in years. It proposed a range of amendments to its rules on credit derivatives, permitting a range of new instruments to draw in more interest. The regulator is accepting comments through February, after which it will announce its final changes. Separately, it also rolled out the red carpet for more foreign funding.

How far can this take us in improving our markets? Will this still leave us with problems we haven’t solved? Here’s what’s in the package, and why it matters.

The building blocks: credit indices

The RBI wants to bring indices into the world of credit derivatives.

Just as the Nifty 50 bundles together the shares of fifty major companies into a single basket, a credit index would bundle together debt instruments — corporate bonds, debentures, money market instruments, and notably, even unrated infrastructure bonds — into a single basket.

That basket, then, allows one to take bets that are more abstract than any one entity’s debt. It might capture the debt of a particular credit grade, or of an entire sector. You could have an index that tracks, say, the debt of India’s largest infrastructure projects, or one that reflects the borrowing costs of AA-rated firms. The index turns a fragmented universe of bonds into a single, coherent idea.

A new generation of derivatives

With an index in place, you can create instruments out of that idea.

The RBI proposes two additional instruments: credit index futures and index-linked credit default swaps (CDS). Both will be exchange-traded, with guaranteed settlement — which means, unlike with a private over-the-counter contract, you aren’t afraid that the other side won’t come through.

In a credit futures contract, two parties are basically betting on how someone’s credit risk might look like tomorrow. An index-wide future, by extension, bets on the credit risk within an entire portion of the economy. If you think there’s a recession scare coming, and it’s going to get harder to get cheap credit, a futures contract lets you take a bet on the index going down.

A CDS, meanwhile, works more like insurance: if you have given someone a loan, for a premium, you can “give away” the risk of default to someone else. In case the borrower does default, you still get paid. India had these on the books since 2013. But they only covered individual bonds. Naturally, there was little demand for bond-wise insurance — especially since most bonds are rated AA or above anyway.

With an index-wide CDS, however, you can buy insurance against defaults across an entire section of the economy. That’s a more interesting bet to take.

By introducing derivatives on indices, RBI is essentially opening the doors to far more sophisticated forms of hedging than before. Imagine a bank that’s heavily exposed to infrastructure lending. It can change the amount of risk it’s taking, at a high level, by taking a position on infrastructure credit broadly.

Think about it, a single issuer’s bond draws few natural counterparties. An index stitches these fragments into one market, where the universe of potential trading partners expands by orders of magnitude.

If it trades, it also becomes a live price signal for credit stress. Every shift in prices carries information — about how the market collectively views credit risk, how conditions are shifting, and where stress might be building. That is extremely useful information — for lenders, borrowers, investors, and everyone else.

Total return swaps: a new animal

Alongside these index-based products, the RBI is introducing something new: the “total return swap”, or TRS.

Where a CDS is essentially default insurance, a TRS isn’t strictly about risk mitigation at all. It doesn’t kick in when something goes wrong. Instead, it lets a party trade away its economic exposure to a bond — its price movements, its coupon payments, everything.

Imagine a bank that holds a five-year corporate bond, paying 8% annually. The bank wants predictability. It doesn’t want changes in the bond’s market price sending its own balance sheet swinging. It could enter into a TRS with a counterparty — perhaps an investment fund looking for exposure to corporate debt. The bank would agree to pass along everything the bond generates (interest payments, any price appreciation) to the fund. In return, the fund would pay the bank regularly, based on the benchmark rate. The bank technically owns the bond, but economically, it has handed it off. The fund, meanwhile, gets to experience the bond’s returns without ever buying it.

More interestingly, though, you can customise how the swap works. You’re no longer beholden to the original terms a bond was issued at. You could, for instance, take on the returns of a bond for just six months. You could take exposure to one-fifth of it. You could combine several bonds into a diversified package. You could adjust the frequency of payments. As long as someone is willing to own the underlying bond and structure interesting configurations around it, you can create anything the market demands.

Last time, we talked about how India’s corporate debt markets lack market makers. It simply isn’t attractive to be a wholesaler of bonds. In an illiquid market, it doesn’t make sense to stockpile debt instruments that nobody wants. But if you can take the exposure off your books and repackage it into bespoke products others might want, those inventories no longer weigh down your books. The case for being a market maker is suddenly much stronger. Even if there isn’t always a market for buying and selling whole bonds, there may be appetite for custom, synthetic slices of their risk.

TRS can’t be offered to individuals. But for everyone else — companies, banks, insurers, mutual funds — there’s no restriction in purpose. Domestic participants don’t need to justify a hedge; they can enter a TRS for any reason they choose.

A red carpet for foreign capital

The more sophisticated instruments in RBI’s package aren’t fully open to foreign investors. While a domestic investor can buy a TRS for any reason, for instance, a foreign investor can only use one to hedge existing exposure.

But the RBI has signalled some major moves, at its most recent MPC meeting, that could draw substantially more foreign capital in.

Until now, foreign investors faced a thicket of restrictions on how much Indian debt they can accumulate. They couldn’t buy bonds maturing too soon, they couldn’t concentrate too much in a single issuer’s debt, and so on. In 2019, the RBI offered a bargain: a programme called the Voluntary Retention Route, or VRR. If foreign investors were willing to lock their money into India for three years, these other restrictions would fall away. But the VRR came with a hard cap. Only ₹2.5 lakh crore could enter India through this route in total, of which just ₹35,000 crore could go into corporate debt.

The RBI held auctions for these limits, asking investors to bid for the right to invest.

By early 2026, over 80% of this limit had been utilised. The route was, in effect, full. Foreign investors who wanted in simply couldn’t get through.

In its most recent meeting, though, the RBI decided to uncap the programme. The VRR is now effectively a flexibility upgrade: if you invest in India with a horizon of more than three years, most of the usual restrictions on where you deploy your money simply fall off. There are no more quotas and no more auctions for access.

There’s more in the works. Authorised dealers — entities licenced to deal in foreign exchange — will likely get more flexibility in the products they can offer. The details aren’t fully clear yet, but the direction is. If you’re a foreign investor putting money into Indian bonds, one of your biggest fears is that a sudden move in exchange rates wipes out your returns. Armed with greater flexibility, authorised dealers could now offer better insurance against that risk.

What these changes do — and don’t do

When we examined India’s bond market last time, we saw a series of interlocking problems. It was difficult to publicly issue debt. There weren’t enough buyers for it anyway. And if you bought debt, there was no market to sell it in. Creating an active bond market from this foundation is an exercise in piercing a chakravyuh.

This package of reforms attempts to begin with the last of those links: the market itself.

The biggest benefit of an index, to our minds, is that it consolidates liquidity. If participants were previously trying to hedge their exposure bond-by-bond, they can now all enter the same common market. The pool of potential counterparties grows. And if TRS work well, they give market makers a reason to actually hold inventory.

Meanwhile, in a country that runs on deficits, the government’s appetite for debt can be large enough to consume most of the savings our economy generates. We need capital from outside. And the removal of VRR caps cleans out the pipes for it to flow in.

It’s worth noting, though, just how contingent all of this is. Well-intentioned regulations, by themselves, can’t create a functioning market. The test of a market, ultimately, is whether anyone wants to trade in it.

Getting this right is a matter of nailing both the design and the execution.

There are many reforms that sound excellent in principle, only to fall apart upon contact with the real world. When India first introduced credit default swaps in 2013, for instance, there were simply no takers. The market just wasn’t attractive enough for anyone to actually use them. There could be something else we’re missing this time around — some friction or misalignment that only becomes apparent once the machinery starts running.

The risks could be more banal as well. The new indices need to be well-designed and robust. The settlement infrastructure for this needs to work smoothly. We could have the perfect regulatory conditions for a market, but if the execution isn’t right, it might end up for nought.

And finally, there are significant issues with India’s corporate bond market that these changes don’t touch at all. They don’t make it easier to issue debt publicly. They don’t loosen the constraints on insurance companies or pension funds that restrict them from investing in anything below AA-rated paper. They don’t reduce the state debt that crowds out corporate borrowing.

This is just the first move in a long campaign.

The flywheel

It’s hard to deny one thing, though: these measures may well be the most coordinated attempt India has made, so far, to give life to its corporate bond market. Underneath all of them is a simple bet — that liquidity will chase liquidity.

The self-reinforcing problems we described last time — where thin markets discourage participation, which keeps markets thin — have a mirror image. When flipped, they’re a flywheel.

If derivatives and synthetic markets take root, they create secondary market activity, because institutions now have tools to manage risk. That activity, in turn, generates more demand from investors, when bonds are issued. And more demand, eventually, encourages more issuance, as companies find that the bond market is finally worth the trouble of accessing. Each turn of this wheel makes the next one easier.

There are no guarantees that this will happen. But if it does, it may well transform how India’s economy is financed.

Tidbits

Carlyle bets big on Edelweiss’ Nido Home Finance

Carlyle is putting ₹2,100 crore into Edelweiss Financial’s housing finance unit Nido Home Finance. The deal includes buying 45% and adding ₹1,500 crore as fresh money into the business. After this, Carlyle-linked funds will control roughly 73% of Nido—basically taking the driver’s seat in a lender focused on housing loans.

Source: Reuters (via Mint)Jubilant FoodWorks Q3FY26: Profit jumps 65% as demand stays strong

Jubilant FoodWorks’ Q3 profit rose 65% YoY to ₹70.9 crore, helped by strong festive demand and more orders. Revenue grew 13.3% to ₹2,437 crore. India growth stayed healthy, Domino’s showed ~5% like-for-like growth, and Popeyes kept gaining traction. The company added 114 net stores, taking the total network to 3,594 outlets.

Source: Reuters (via Business Standard)Adani enters nuclear power with a new subsidiary

Adani Group has set up Adani Atomic Energy, a wholly owned subsidiary of Adani Power, marking its formal entry into nuclear energy. The new unit’s job is to generate, transmit, and distribute electricity made from nuclear/atomic sources—signaling Adani’s interest in being part of India’s next phase of power expansion beyond thermal and renewables.

Source: NDTV Profit

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉