Hello and welcome back to Beyond the Charts. A series where we break down what's happening in the world of finance and the economy through charts in a way that's easy to understand.

A tale of two markets

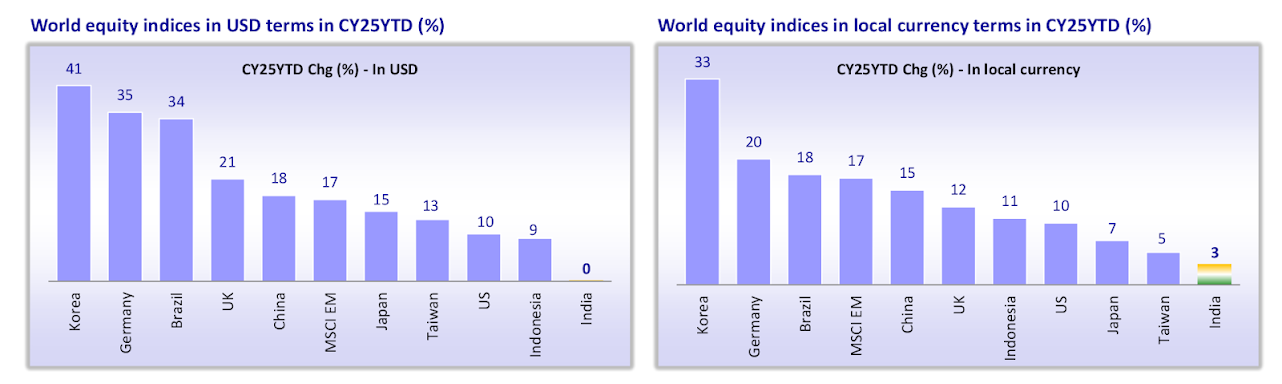

2025 has been a tale of two markets. Globally, equities are enjoying one of their strongest runs in years. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is up 17%—its best run since 2017. The S&P 500 has gained nearly 15%. Korea has surged 41%, Germany 35%, and Brazil 21% in dollar terms.

India, on the other hand, has barely managed 3–4% gains this year. That puts it near the bottom of the global leaderboard, as this chart from Motilal Oswal shows.

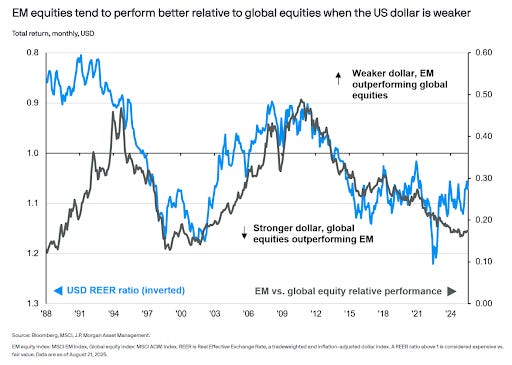

A lot of it comes down to the U.S. dollar. The dollar index has fallen 8% this year, and history shows emerging markets usually shine when the dollar weakens. JP Morgan notes that investors poured $16.3 billion into EM equities in July alone—the biggest monthly inflow in over a year.

The weaker dollar has also boosted returns through currency effects. Roughly 7% of Korea’s gains and 12% of Latin America’s this year came purely from dollar depreciation.

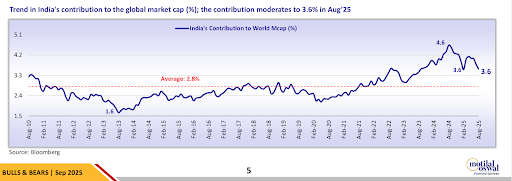

India, though, hasn’t captured the same upside and has seen its contribution to the global market cap slip to 3.6% from a peak of 4.6% in February last year.

So why hasn’t India shared equally in the global rally?

The simple answer is valuations and flows.

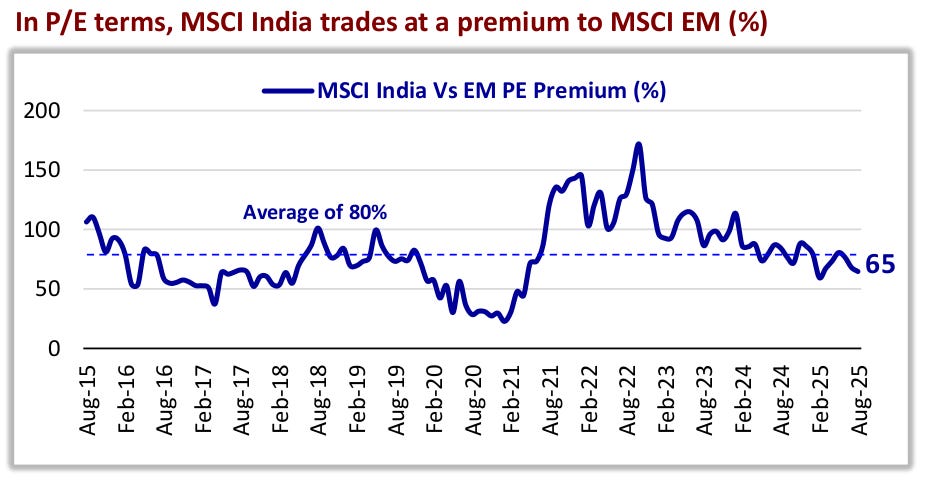

India has long been one of the most expensive markets globally. The MSCI India index trades at a 65% premium to MSCI EM on P/E. When cheaper opportunities opened up in Korea, Taiwan, and Brazil, global investors rotated money there instead.

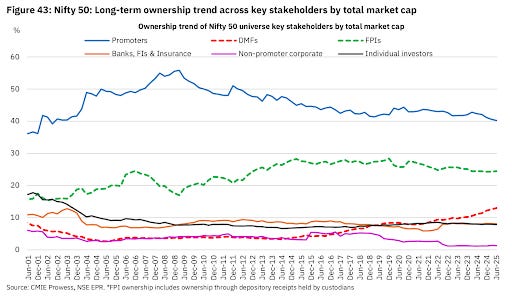

At the same time, foreign portfolio investor (FPI) positioning in India is at its weakest since 2000. Domestic investors—through SIPs and mutual funds—have stepped in to fill the gap. Households now own 18.5% of the market compared with 17.3% for FPIs. But the lack of fresh foreign flows has kept India’s relative performance muted.

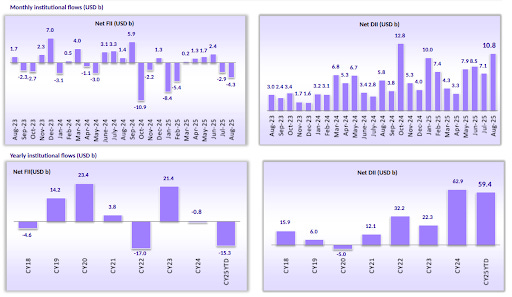

In dollar terms, DIIs have infused a record $83 billion since September 2024—more than offsetting FII outflows of $27 billion. August 2025 alone saw the second-highest monthly DII inflow ever at $10.8 billion, even as FIIs pulled out $4.3 billion.

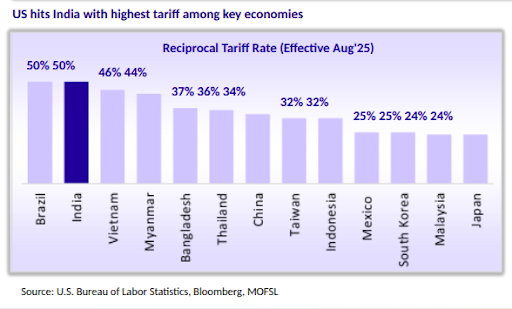

On top of valuations, trade frictions have added to the headwinds. The U.S. has imposed a 50% reciprocal tariff on India, among the steepest faced by any major economy.

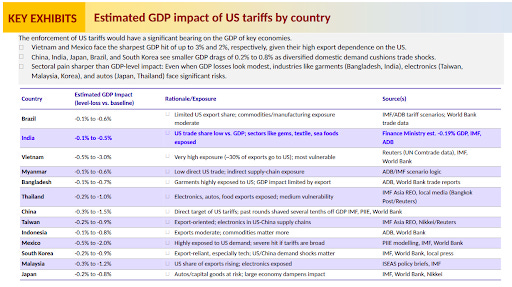

The GDP-level impact of these tariffs looks modest at –0.2% to –0.8%. But sector-level damage is sharper, with textiles, gems & jewelry, and seafood exports taking a hit, as per the Motilal Oswal report.

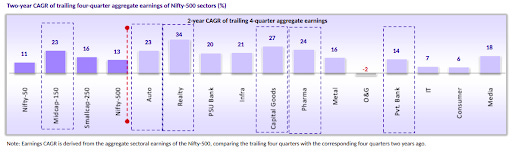

Market performance has been uneven across segments. Over the past 12 months:

Large caps fell 3%.

Midcaps slipped 6%.

Small caps dropped 11%.

Earnings, however, tell a different story. Midcaps have delivered stronger earnings growth than prices suggest, led by real estate, capital goods, pharma, and private banks.

On the policy side, the GST reforms announced on 3rd September didn’t move the markets much at first. But they could support consumption and earnings in the months ahead. The new structure simplifies rates into three slabs: 5% for essentials, 18% for most goods, and 40% for luxury and sin items.

For a deeper breakdown, check out Friday’s edition of The Daily Brief.

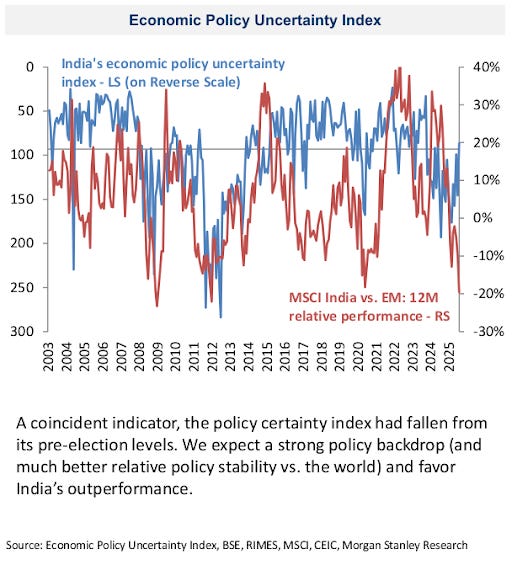

To add some structural context, Morgan Stanley calls India a “low-beta” market. It falls less during global downturns but lags during bull runs—exactly what we’ve seen in 2025.

At the same time, India’s policy stability stands out against its peers. On their index, India has among the lowest “policy uncertainty” scores, supporting its long-term case even if short-term flows remain volatile.

To sum up: Indian markets have lagged global peers, held back by high valuations, weak foreign inflows, and tariff-related uncertainty weighing on sentiment. Domestic investors, however, have stepped in to keep markets stable in the absence of FIIs. With GST reforms likely to boost consumption, it might help improve the sentiment.

Rural India: From stagnation to signs of a comeback

When we talk about India’s economy, the spotlight usually falls on cities. But nearly two-thirds of Indians live in villages, and what happens there shapes everything from company earnings to government policy.

The last few years, though, have been tough for rural India. Ambit Asset Management’s August 2025 newsletter calls the past three years “particularly challenging.” Wages barely moved, prices of essentials shot up, and demand for two-wheelers, soaps, and packaged food weakened. Families cut back to just the basics.

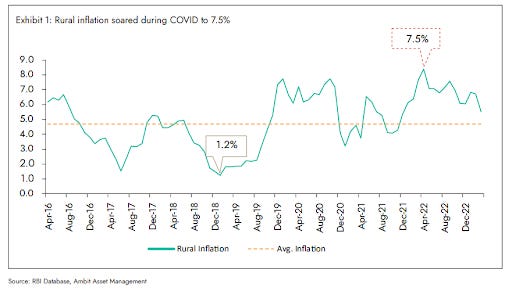

Take inflation, for example. During COVID, rural inflation soared to about 7.5%, much higher than the long-term average.

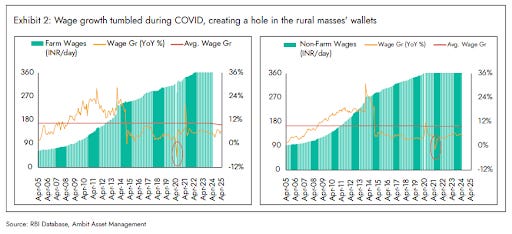

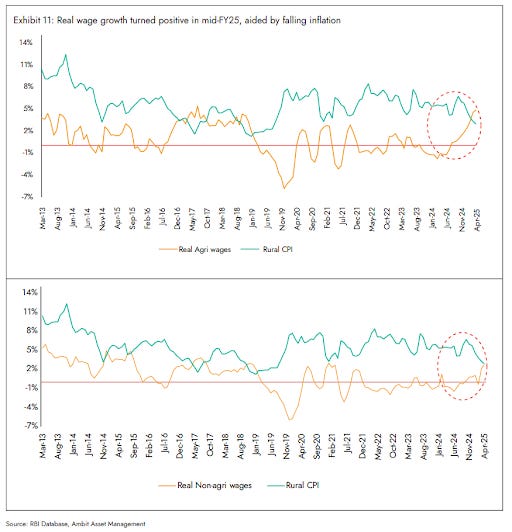

At the same time, farm and non-farm wages stagnated. For many workers, real wages—basically, income after adjusting for rising prices—actually fell. That meant less money left in pockets, smaller savings, and lower spending.

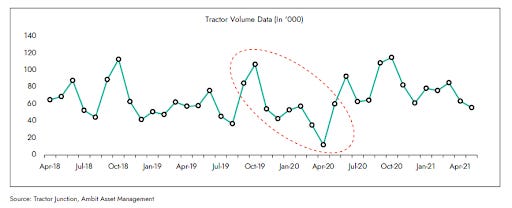

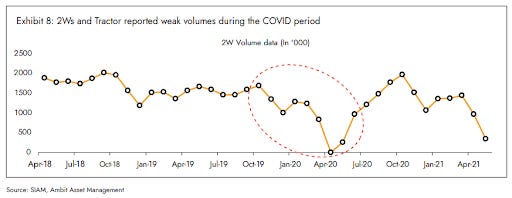

Two of the best indicators of rural prosperity are tractor and two-wheeler sales. Together, they tell a clear story: a rough patch, followed by early signs of recovery.

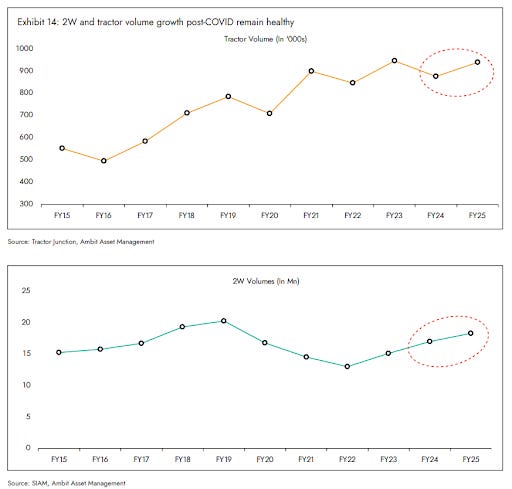

From FY19 to FY25, tractor sales grew only ~3% annually, well below the ~7% long-term trend. There was a brief jump in FY21–FY22 after good monsoons and post-COVID pent-up demand, but it didn’t last.

Two-wheelers show the same pattern. Around 56% of them are sold in rural India, mostly in the sub-110cc entry segment. But this segment still hasn’t returned to FY19 peaks. Prices for entry bikes are up ~35–40% since then (due to emission upgrades, safety norms, and higher costs), while rural wages barely budged, making upgrades harder.

The good news is that this downbeat trend might be changing. By FY24 and FY25, volumes have started picking up again. Tractor sales were up 9% year-on-year in June 2025 and 8% in July. Two-wheeler sales also saw mid-single-digit gains. Early signs suggest rural households are beginning to loosen their purse strings again.

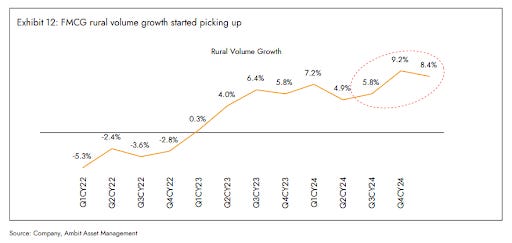

FMCG companies like HUL and Dabur, which saw weak rural demand in FY22–23, are reporting some recovery as consumers move back to larger packs. Rural housing construction is also showing signs of life, helped by easing input costs.

The monsoon this year has been kinder—rainfall has been slightly above average and better distributed. By July-end, Kharif sowing was 8% higher than last year, setting the stage for stronger farm output and incomes.

Wages, too, are improving. After years of stagnation, real rural wage growth turned positive in mid-FY25, thanks to lower inflation and more government spending on rural infrastructure. Demand for MGNREGA work has even dipped, which usually signals better job availability elsewhere.

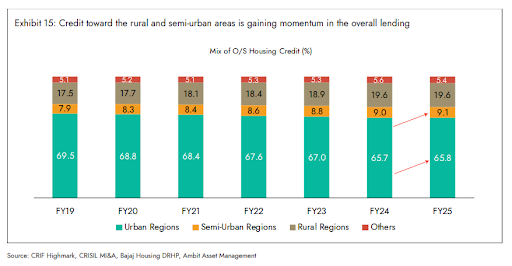

Credit is flowing more into smaller towns and villages too. Between FY19 and FY25, the share of outstanding housing credit going to rural and semi-urban India has edged higher.

So it looks like the rural economy, which had been stuck in a slowdown, is finally turning a corner.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading and do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Thanks for Great Article . Up to the point . Clean and crisp 👏