Why India Can’t Build the Next Apple or Tesla

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why we struggle to innovate

Delhivery added Ecomm express to its cart

Why we struggle to innovate

Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal just struck a raw nerve in the Indian start-up ecosystem.

Speaking at the ‘StartUp Mahakumbh’, he claimed that Indian start-ups needed a ‘reality check’. The sorts of businesses that Indian start-ups are entering — most of them consumer-focused, from quick commerce to healthy ice creams — weren’t really start-ups, he said; they were closer to simple, traditional businesses that didn’t push us forward as an economy. He contrasted our start-ups with the sort of deep tech startups that you see in China. We need more innovation, he said, so that it could take its businesses across the world.

His clincher was this comparison:

Ouch.

This sparked a huge social media flame war, because of course it did. Start-up founders returned his charge with their own counters: Indian start-ups are doing important work; India’s economy doesn’t yet have room for deep tech start-ups; the Indian government is sclerotic and unconcerned; and its unending appetite for bribes and licenses kills businesses.

Our view? Many things can be (and often are) true at the same time.

India does lag the Chinese economy; as does our deep tech ecosystem. We’re nowhere close in a head-to-head match (check out Finshots for examples of where we stand). We’ve spoken before about how China’s innovation ecosystem came about, though, and isn’t always pretty. China’s innovation strategy is deeply inefficient and frequently gamed. It pits hundreds of start-ups together in a bout of what some call “hunger games capitalism”. It is a strategy that is meant to create national champions, but at the expense of its traditional economy.

At the same time, we are serial laggards in the realm of innovation. This is a sphere where we routinely punch well below our weight. We are simply absent from some of the world’s most dynamic industrial sectors, and serially under-invest in research and development.

But why? What’s actually holding us back? For answers, we’re digging through a recent paper by Sarthak Pradhan and Pranay Kotasthane from the excellent Takshashila Institution. Here’s what we learned.

Why do countries innovate?

First, let’s flip the question — instead of wondering why we don’t innovate enough, let’s ask: why do countries innovate?

The answer, as you might expect, is complex.

There’s no single thing that guarantees innovation. There are, instead, dozens of things that matter at the same time — from what a company’s leadership is looking for, to the quality of its workforce, to the networks it’s embedded in. Here’s an indicative list of the kinds of things you should look for:

This list is only a beginning. The truth is that these factors usually play off against each other in a variety of ways. Pranay and Sarthak have this fascinating, if somewhat confusing, chart that lists out all the ways in which these different ingredients come together:

Now, they do point to specific, less-confusing problems that India has, and we’ll get to those soon enough. But if there’s one thing to take away from that intimidating web of connections, it is that there are no easy answers when it comes to innovation. There’s no single ingredient that can suddenly make us an R&D powerhouse. Simplistic answers won’t get us very far — because there are many other things that will naturally stop our progress.

If we open more IITs, for instance, but don’t have an industrial base to absorb their graduates, we’ll simply create more workers for foreign companies.

If we set up government schemes to subsidise deep tech companies, but those same companies then struggle with archaic land and labour laws, we’ll end up wasting a lot of money for nothing.

And so on.

A smarter way of going about this question is to try and understand the various relationships between everything that goes into making an innovative economy. Among other things, this lets us find points of leverage — small interventions that set off large chain reactions, all of which collectively allow innovation to bloom.

So what’s holding us back?

With that, let’s get into the specifics — with all the bad loops India is stuck in that is stunting our innovative potential. These problems aren’t specific to our inability to make AI models or EVs; they’re deeper problems with our economy. Our poor innovative capacity is just one more symptom of these problems.

There just isn’t enough investment

Let’s start with the obvious: innovation requires money. And India doesn’t have much to offer.

To create innovative products, India needs investors that are willing to take big bets on ideas that could easily fail, and then hang in there patiently. Sadly, India isn’t there. If anything, India’s private investment has fallen — from 27% of GDP in 2011–12 to under 20% by 2020–21. Our inability to draw private investment, as we’ve mentioned before, is the Achilles’ heel of our economy.

Innovation is yet another place where this problem plays out. As our overall investment levels fall, so does our investment into innovation. The result is clear: our R&D spending is a limp 0.64% of GDP — far behind China (2.4%), Germany (3.1%), or South Korea (a massive 4.8%).

For a more vibrant innovation ecosystem, then, we need to have a better investment ecosystem in general. What can we do better? There are many answers to this question, and we’ve pointed to some of them before. Pranay and Sarthak train their focus on taxation.

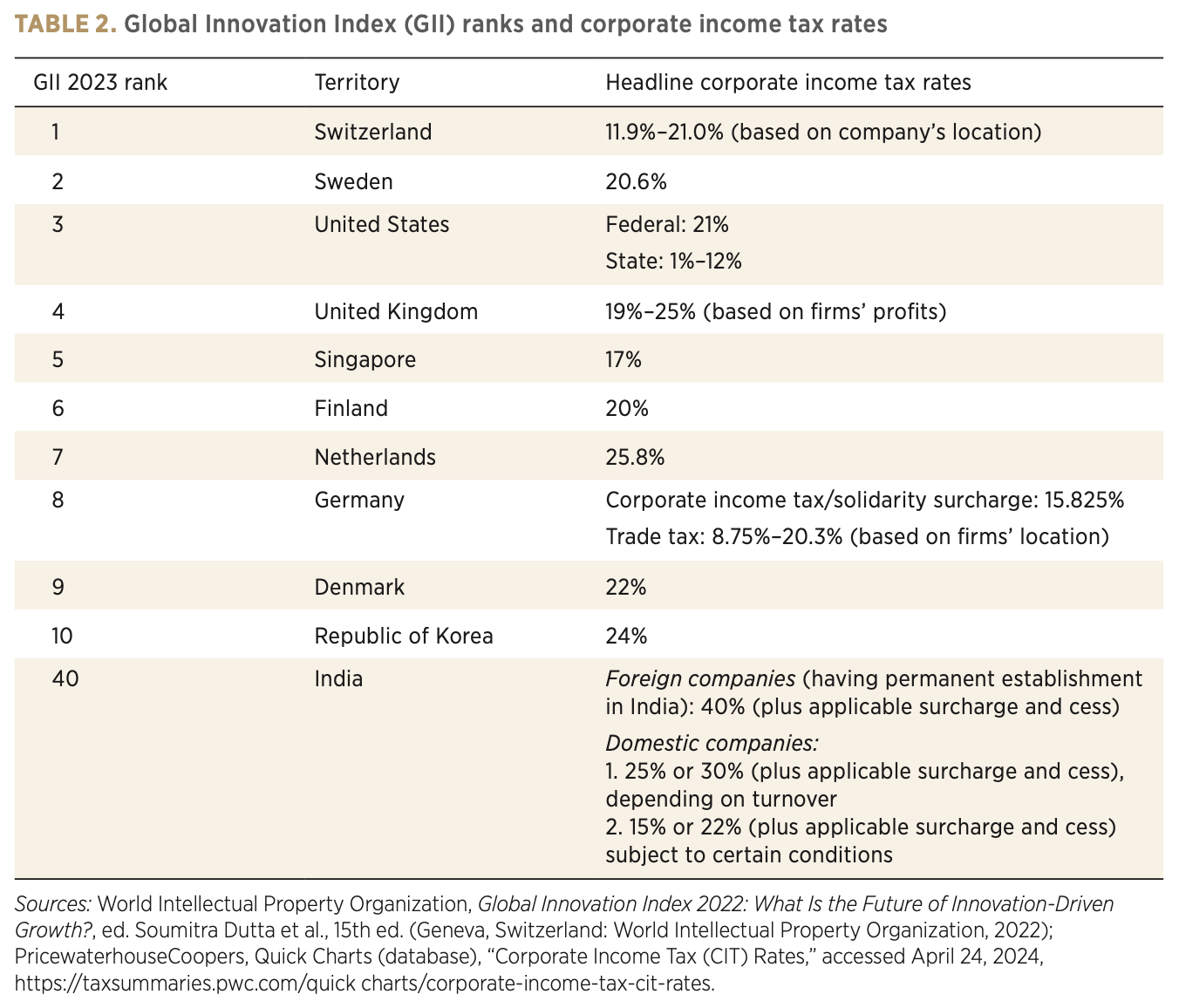

For one, we just charge really high taxes. Foreign corporations get the worst end of the stick — with taxes that, excluding surcharges and cesses, can go as high as 40%. Even our domestic firms are hit with relatively high taxes.

But companies could find their way around somewhat high taxes, if they’re stable. Our bigger problem is the sheer confusion that our tax laws create. We have imprecise laws that are constantly shifting. Indian companies deal with a constant tangle of shifting rates, cesses and surcharges. Tax raids are common.

One of the consequences of this complicated taxation regime is a phenomenon called “flipping”. Basically, many start-ups move abroad to foreign jurisdictions like Singapore — taking everything from the intellectual property, to their management. Around 56% of India’s unicorns, in fact, are domiciled abroad. The value they create, the IP they generate, and the capital they raise — all of it shows up on someone else’s books.

We can’t keep our talent in place

India’s education system has a big problem. We aren’t good at training most of our people — which is why we have such a severe ‘employability crisis’. Most of our graduates don’t have the skills that Indian industry needs. In fact, our education system is built around sorting. At its core are massive, India-wide exams like the IIT-JEE, which are built around identifying the cream of Indian talent.

Once we spot India’s best talent, we’re unable to keep most of it here. For instance, a recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) found that of the top 1,000 scorers of IIT-JEE 2010, over one-third had already left the country. Among the top 100 scorers? Nearly two-thirds. We’ve become a pool for others to pull talent from. We contribute the largest pool of high-skilled emigrants to the OECD. Meanwhile, we attract almost no talented expats from other countries.

Why is this the case?

For one, India simply isn’t an attractive place to live — at least for people who would be welcomed wherever they would like in the world. We have poor living standards, and limited opportunities.

Equally, our poor education standards mean that we aren’t a particularly productive economy. For extremely talented or skilled Indians to thrive, one needs a large base of skilled workers. These are the people that would bring all their vision and talents to fruition. In India, that is simply missing, even though we are theoretically the world’s second largest workforce. Consider, for instance, that workers in the United States are nine times as productive as Indian workers. Even Chinese workers are twice as productive. Our poor human resources are a big drag on the innovative work our people can do.

Our businesses struggle to grow

One of our messiest problems is that Indian businesses don’t scale. We went into this in greater detail last week when we were talking about Indian MSMEs’ struggles to expand.

To recap, though, our policies are deeply unfriendly to businesses. Our labour regulations, for instance, are a severe drag on business — with provisions that micro-manage everything from how many spittoons a factory has to how many clotheslines it must provide workers. Important management decisions, such as those on hiring and firing, must be run by local labour officials. These create unwanted headaches for Indian businesses, and pull down how productive they are.

It is no surprise, perhaps, that many of India’s startups are built around bringing excess labour to simple challenges.

Perhaps to compensate Indian businesses for such drags on their productivity, we have shied away from international trade. This has been counter-productive. When businesses can access international markets, they’re incentivised to innovate more — for various reasons. They face more competition. They interact with more businesses, and can learn better business practices. If they succeed, they get a larger market to profit from.

Instead, as a matter of policy, we’ve shied away from foreign markets. We have some of the highest trade barriers for any major economy in the world, in fact. Indian businesses build for small segments of India alone — which isn’t a recipe for globally relevant innovation.

Lack of a research ecosystem

We don’t have a focused suite of policies that could spur research.

Consider tax breaks. Governments around the world give tax breaks to encourage private R&D. India used to do this well. We offered a 200% deduction on any money spent on research until 2016 — and studies showed that these breaks were actually effective in spurring research. But in recent years, we've scaled it down to 100%.

Other countries have been moving in the opposite direction. Even as we were cutting down on R&D tax breaks, for instance, China was ramping up programs like its Thousand Talents program, which lured back 7,000 researchers from foreign universities between 2011 and 2021. This improved China’s research ecosystem considerably, while linking Chinese research with the rest of the world.

We don’t have the foundations for a program like this. Our research institutions are mostly standalone government labs, divorced from universities. This is where most of India’s R&D investment goes. In the U.S., academia gets 30% of federal R&D funding. In India? Just 5%. The rest goes to government agencies — which often run their own research in-house, without competitive grants or external collaboration. Indian industry, too, is cut off from this system.

That means our research is less dynamic, and we offer fewer reasons for our top talent to stay or return.

The cherry on top: Our patent system

Finally, for good research to flourish, you would expect policies that help people maximise the fruits of their research. India doesn’t offer that.

Until 2005, India didn’t even recognize product patents. This discouraged businesses from creating new products. While we’ve come a long way since, our patent system is anaemic. We don’t have enough patent examiners, and the few we do have lack expertise. As a result, today, patent exams in India take up to five years — more than double the global best.

We don’t have a good system to adjudicate patent disputes either. We used to have an appellate board to handle patent disputes. This performed sub-optimally, however, and was scrapped in 2021 — because we were struggling to appoint the members and experts we needed. Everything now goes to already-jammed High Courts, however, which isn’t much better.

Where does this leave us

India’s innovation woes aren’t just a problem of its start-ups — that’s merely a symptom of far deeper problems with the design of our innovation ecosystem.

Innovation doesn’t bloom in a vacuum. It needs fertile ground — patient capital, policy consistency, skilled people, open markets, and research ecosystems that talk to each other. Right now, too many of those ingredients are either missing, mismatched, or muddled up by our own systems. Without that, small fixes, like the odd IIT, or start-up subsidies, are unlikely to move the needle.

So yes, our Commerce Minister is right to say we need more innovation. But that won’t be achieved by start-ups abandoning their healthy ice cream plans. It’ll need a ground-up rethink of what creates innovation, and everything that acts as a drag on our ability to get there.

Delhivery added Ecomm express to its cart

Delhivery just announced something very interesting: it's acquiring its arch-rival Ecom Express for ₹1,407 crore in cash.

That’s a big deal — precisely because it’s a small one. Less than a year ago, Ecom Express was valued at ₹7,300 crore. It was gearing up for an IPO, in fact. Now, it’s being bought out for a fifth of that price. This isn’t just some other acquisition; this is one of the largest logistics players in the country buying up a rival for pennies on the Dollar.

Something has shifted in this last year — not just for Ecom Express’ valuations, but for India’s logistics space in general. While we don’t have all the facts just yet, here’s everything we know.

So how did Ecom Express end up here?

Ecom Express used to be a big name in logistics. It was backed by top-notch names from the PE world, like Warburg Pincus. When it filed its Draft Red Herring Prospectus (DRHP) last year, it claimed to be India’s only pure-play B2C e-commerce logistics company. In fact, it claimed to fulfill 27% of all of India’s B2C e-commerce shipments — the second largest in India.

Not everyone bought its story, back then. Arch-rival Delhivery, one of the biggest names in the space, saw big problems in its filings. When Ecom Express’ DRHP compared its performance to Delhivery, Delhivery shot back — publicly claiming that Ecom Express’ figures were somewhat over-stated.

But then came a twist in this rivalry.

Ecom Express had one Achilles’ heel, tough: concentration risk. Three-quarters of its revenue came from its top five clients. The biggest of these was Meesho, one of India’s major e-commerce platforms. At one point, over 50% of Ecom’s revenue came from this single client.

While things were good, this was a source of a lot of business. But then, Meesho decided to do its own deliveries through its in-house arm, Valmo. Just like that, half of Ecom Express’ business evaporated. That coincided with a slew of other problems: slowing shipment growth, top leadership exits, and a failed IPO attempt. Ecom Express was in a tight spot.

And now, Delhivery is buying it outright, for a fraction of the valuation it had half a year ago.

What does Delhivery get out of this deal?

To understand that, let’s step back and look at how logistics actually works.

Say a t-shirt is made in a factory in Ludhiana. First, raw materials are brought into the factory. This is called first-mile logistics.

Once the shirt is ready, it’s moved to a different warehouse, say in Delhi. This is mid-mile or line-haul.

When you order the T-shirt online, it travels to a local delivery center, and finally to your doorstep — that’s last-mile delivery. If you don’t like the shirt and return it, the whole process runs in reverse.

Delhivery operates across almost every part of this chain. It picks up goods from sellers, moves them across cities through large trucks (that’s full-truckload, or FTL), ships smaller loads that share space with other businesses (that’s part-truckload, or PTL), stores products in warehouses, processes orders, and delivers them to customers. Most importantly, it does this for thousands of clients across the country — from massive marketplaces to small D2C brands.

Ecom Express’ business model, on the other hand, targeted a much smaller segment of the industry: it was built almost entirely around e-commerce. Its strength was in doing first-mile pickups, moving shipments through its network, delivering parcels to your doorstep, and handling returns. It also offered warehousing, but mainly as a bolt-on service for online sellers.

So there’s significant overlap here. Both companies deliver packages, manage returns, and offer storage. But Delhivery’s business is much larger. It does all of this at a much larger scale, with more complexity involved. It also manages large freight loads, offers tech platforms, and has a more diversified customer base.

That’s why this acquisition, with the limited knowledge we have, feels a bit confusing. Delhivery already does what Ecom Express does—and arguably, does it better. According to their own numbers, express parcel services alone make up over 60% of Delhivery’s revenue today, and they’ve been expanding their PTL, FTL, and warehousing businesses steadily.

So this deal doesn’t unlock a new line of business. It just adds more firepower for the same stuff.

What it might do is give Delhivery more volume, more pin code coverage, and maybe a few large clients who were still loyal to Ecom. It could also make Delhivery stronger when it comes to pricing negotiations, since there’s now one less big player in the express parcel space.

There’s also the possibility that this was just a valuation play—Ecom was going cheap, and Delhivery had the cash.

Not all acquisitions succeed

But even then, the big question is: does this actually change anything for Delhivery?

They’ve been down this road before. In 2021, they acquired Spoton. That was meant to boost Delhivery’s part-truckload freight business. After the deal, though, revenue from Spoton’s business reportedly dropped sharply, and the company faced severe challenges in integrating this new unit. That history makes this deal feel riskier. While acquisitions sound glamorous, the subsequent integration isn’t easy — people leave, systems don’t align, and synergies don’t always show up the way spreadsheets promise.

Of course, Delhivery is a dominant player, and it has only expanded that dominance. It just bought out a struggling rival at bargain prices, which might give them more scale and power. But is that enough?

After all, something being cheap doesn’t automatically mean it’s valuable. Especially if you already do most of what the other company does. Which leaves us wondering — what really changes now for Delhivery as a business?

We don’t know, but we will find out soon.

Tidbits:

Tata Motors is staring at a revenue dent as Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) halts exports to the US for April 2025, following a 25% import duty announced by US President Donald Trump. The US accounts for 15% of Tata Motors’ consolidated revenue, which stood at ₹4.37 lakh cr. in FY24. The US remains a key destination for shipments from JLR’s Solihull plant in the UK. JLR alone brought in 69% of Tata Motors’ overall revenue last fiscal.

Skoda Auto Volkswagen India is under scrutiny for alleged delays in tax assessments amounting to $1.4 billion (around ₹11,526 crore), according to an affidavit filed in the Bombay High Court. The dispute concerns the classification of imported components brought into its Aurangabad facility between March 2012 and July 2024. Authorities claim the imports should have been declared as Completely Knocked Down (CKD) kits, which attract a different customs duty. A total of 10 cases involving related-party transactions are being investigated by the Special Valuation Branch, and Skoda has been accused of submitting required documents in parts and not furnishing all information.

Brent crude prices dropped nearly 4% to $63.01 per barrel after Saudi Arabia cut the official selling price of its Arab Light crude for Asian buyers by the most in over two years. West Texas Intermediate followed suit, trading at $60.63. The surprise decision by OPEC+ to raise output has added to downward pressure on oil markets, with traders now facing mixed signals about global supply.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna

📚Join our book club

We've recently started a book club where we meet each week in Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you'd like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great breakdown on innovation ecosystem. Furthermore, our commerce minister also needs to keep in touch with the reality of this country and people.

The rider working in Zomato will probably never work in a chip fab facility, but the income he generates might support his siblings who just might.

The labor of gen 1, will get us to gen 2 work force so there was absolutely no need to lose patience.

Demeaning any labor is not going to help this country.

On a parallel track, here's an article which talks about why the US itself can't industrialist. Awesome. In-depth insights, many of which apply to us too.

https://open.substack.com/pub/herecomeschina/p/america-underestimates-the-difficulty?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=2o2kcj