Why CAFE-3 has carmakers worried... and Why AI can’t replace humans yet | Who said what? S2E23

Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna.

Today, we complete one year of Who Said What?. We started this show as an extension of The Daily Brief because we kept coming across fascinating comments from business and finance leaders that deserved more room than we had there. Thank you for watching every Saturday and helping me keep my job.

Now, For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about. The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

For all the sources mentioned in this video, don’t forget to check out our newsletter; the link is in the description.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Maruti, Tata Motors, and Mahindra are fighting about CAFE 3 norms

While researching for stories this week, I came across a very strong comment from Rahul Bharti of Maruti Suzuki, India’s largest carmaker. Here’s what he said:

“The risk is that if the targets become unscientific and unjust, Then, just to meet CAFE-3 regulation, a small car -- which produces a very low absolute carbon dioxide -- will have to be discontinued.”

For a company that more or less built the Indian small-car market to say, out loud, that a new policy might force it to kill small cars is a very big deal. Now, the obvious question is, why would he say this?

Let me give context on what CAFE norms are. See, whenever a petrol or diesel engine runs, it burns fuel and produces carbon dioxide. You can improve the engine, you can make the car lighter, you can tweak the gearbox, but as long as you are burning fuel, CO₂ comes out of the exhaust. A small hatchback burns less per kilometre than an SUV, but both burn something. An electric car is the only one with zero CO₂ at the tailpipe because there’s no combustion happening in the car at all.

CAFE stands for Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency. It doesn’t look at one car. It looks at all the new cars a company sells in a year and calculates the average CO₂ emissions across that entire fleet.

Some cars will be gas-guzzlers, others will be efficient. What matters is where the company lands overall. So if a carmaker sells a bunch of big SUVs that spew out a lot of CO₂, they need to balance that out by selling enough smaller, cleaner cars – or EVs – to bring their average down.

The government sets a target. If a company’s average comes in above that, they pay a penalty on every car they sold that year.

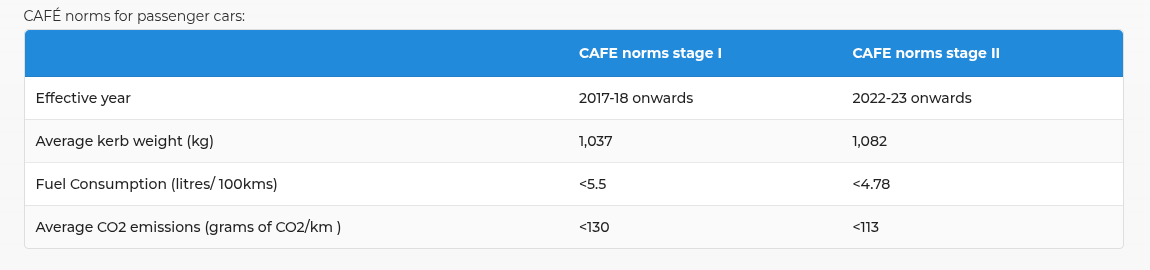

India has already done two rounds of this. CAFE-1 came in around 2017–18, CAFE-2 from 2022.

CAFE-3 is what’s coming next – covering roughly FY28 to FY32.

The draft rules make life harder for carmakers in a few ways. First, the CO₂ target itself is getting stricter – companies will have to hit a lower number than before. Second, the way emissions are measured is changing. The new test cycle is closer to how people actually drive, which usually makes the numbers look worse on paper.

And third – this is the tricky bit – the government is changing how it hands out bonus points. Right now, certain technologies like CNG or mild hybrids get extra credit in the formula. That helps bring a company’s average down, even if the cars aren’t that much cleaner. The new rules could shrink those bonuses.

That’s where Maruti’s worry comes from. Rahul Bharti’s first complaint is about how little help small cars are getting.

In the September 2025 draft, the government offered a small relief for petrol cars that are light (under 909 kg), have small engines (below 1,200 cc), and are small in size (under four metres). If a car ticks all those boxes, it gets 3 grams per kilometre knocked off its CO₂ number in the CAFE calculation.

His point is that this is nothing.

Three grams is a rounding error. He says in Europe, small cars get an 18 gram relaxation which is six times more. So if the overall CAFE-3 target is set really tight, that tiny 3-gram bonus won’t be anywhere near enough to keep small cars alive in the math.

Why does this land so hard for Maruti in particular? Because nobody in India sells more sub-909-kilo cars than they do. For decades Maruti has made its money selling exactly these light, fairly simple petrol hatchbacks. It has some hybrids now and will have more EVs in future, but it does not yet have the kind of EV volume that can drag its fleet average down the way Tata’s or, eventually, Mahindra’s can. In that context, when Bharti talks about “unscientific and unjust” targets and the risk of discontinuing a small car that already “produces a very low absolute carbon dioxide”, what he is really saying is: if you set the average too low and you don’t give small cars much recognition, the maths will eventually make these cars impossible to keep in the portfolio without paying big fines.

And here’s where it gets interesting, because the rest of the industry doesn’t agree with Maruti at all. Tata Motors and Mahindra & Mahindra are against this idea of giving extra relief to very small petrol cars. They don’t want the CAFE-3 rules loosened in the way Maruti wants; if anything, they want the electric-vehicle part of the rule to stay strong.

Tata today is the country’s largest electric-vehicle maker. Cars like the Nexon EV, Tiago EV, Tigor EV and Punch EV make up a meaningful share of its sales. In the CAFE formula, those EVs behave almost like anchors: each one has a CO₂ value of zero, which means every electric car pulls the company’s overall average down sharply. So Tata’s concern is completely different from Maruti’s. When the new draft reduced the credit EVs get in the calculation, Tata pushed back. Their point is simple: we’ve invested heavily in electric, and EVs should continue to get strong treatment inside CAFE.

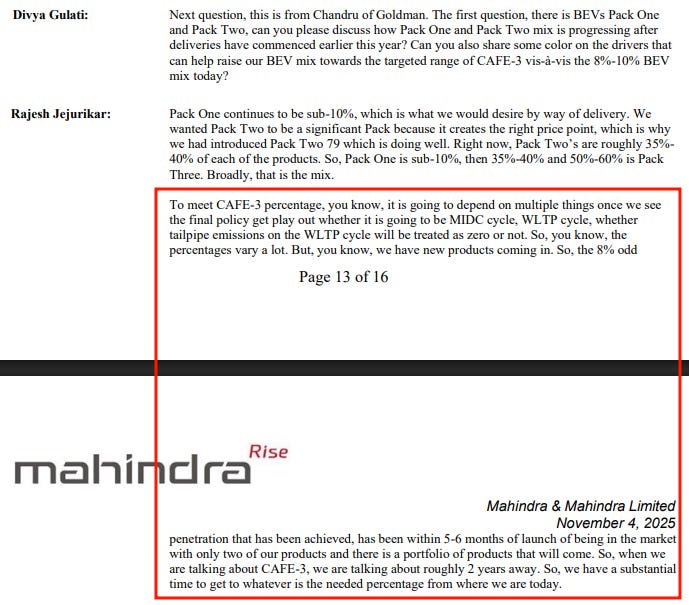

Mahindra’s logic also runs counter to Maruti’s, but for a different reason. Most of Mahindra’s volume today comes from large SUVs — Scorpio, XUV700, Thar — which naturally carry higher CO₂ numbers. On the surface, you’d think CAFE-3 would be hard for them. But Mahindra is in the middle of shifting its portfolio. On their concall, Rajesh Jejurikar, the CEO, spoke about EV momentum. He pointed out that Mahindra’s current EV penetration — around eight percent — has come within just five to six months of launching only two EV models, and that a much larger set of EVs is coming over the next couple of years. And because CAFE-3 only kicks in around FY28, they believe they have more than enough time for their EV ramp-up to bring their fleet average safely within the limit.

It leaves the industry standing on opposite sides. Maruti is fighting to keep small petrol cars viable inside the system. Tata and Mahindra want the system to lean harder toward electric. And caught between these two views is the small, affordable hatchback — the car that still matters more than anything else to most Indian families.

The ex-CEO of Infosys on how AI is evolving

Recently, Indian VC fund Stellaris did a very insightful interview with Vishal Sikka, the former CEO of Infosys. They spoke about a wide variety of topics from the evolution of enterprise software, cloud to the future of India’s IT services industry in the age of AI. And, I wanted to share some interesting quotes that stood out to us.

The first quote is about whether AI could kill packaged software (or SaaS products). Now that LLMs have made writing code through prompts alone a lot easier, the logic goes, anybody can write their own software for their own company instead of using a third-party product. There is a huge opportunity, Sikka says, in making the process of answering business questions from your own data much easier without third-party software:

In fact, he mentions that within IT, data analytics alone is a huge disruption point. One of our teammates, Manie, worked on data analytics in a past life, and he couldn’t agree more:

Yet, interestingly, Sikka also believes that, as of right now, LLMs have no enterprise-grade application:

Interestingly, one potential answer to why this is could be company culture. Every company (and every industry) is unique in its own way, and will need time to integrate LLMs into their own build. Here’s what Sikka says:

A fantastic example he gives is that of pharma major GlaxoSmithKline, on whose board he serves:

Of course, Sikka was also asked about the future of the industry he once led. In fact, in his time at Infosys (2014-17), he was already working with OpenAI in some capacity:

And now, he’s already spotting some early signs of the deflationary effect of AI on Indian IT:

With this interview, we get a sense of not just the threats that AI poses to existing incumbents, but also opportunities for new Indian entrepreneurs. To a degree, we’re seeing many of these effects in the quarterly results, too. We highly recommend watching the whole interview if you have the time.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

The purpose of CAFE norms was to reduce the CO2 emissions and Maruti is busy fighting the regulation instead of bringing in innovation.

When they do such things, it is evident of how they do not care about the pollution in our cities and just want to protect their business.