Why Are India’s Top Banks Taking a Breather?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s top private banks are on cruise mode

CNG is losing its spark

India’s top private banks are on cruise mode

India’s top private banks have reported their Q4 FY25 (Jan–Mar 2025) earnings, and this results season reveals a complex story: a mix of steady loan book quality, moderated growth, and cautious optimism for the year ahead. Today, we’ll focus on three banking heavyweights – HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, and Axis Bank – leaving aside the public sector players for now.

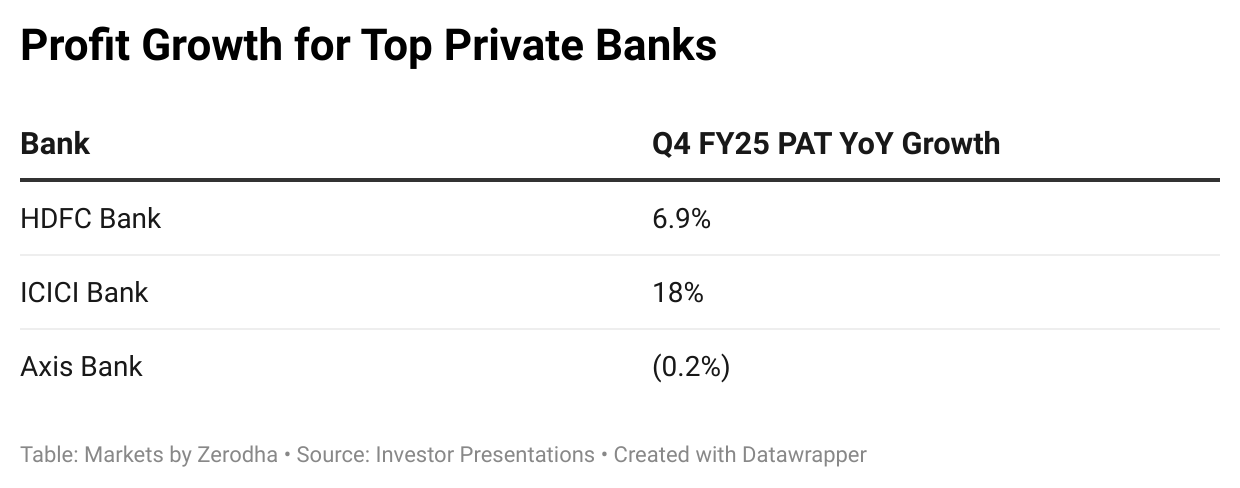

The bottomline? All three delivered profits and stable operations, even though growth has clearly fallen from the blistering pace of a year ago. ICICI Bank led the sector on bottom-line performance with an 18% year-on-year jump in quarterly profit, outpacing HDFC Bank’s 6.7% rise and Axis Bank’s essentially flat earnings.

But those are just the headline numbers. Equally, the March quarter results reveal important trends in asset quality, growth, and margins for these private lenders.

Asset quality is steady as ever

Asset quality remained a bright spot for India’s big private banks. Although there are some industry concerns around specific segments (like microfinance, construction or unsecured retail loans), large private banks have stayed resilient.

Now, that doesn’t mean everything is hunky-dory. There is indeed continued stress among Microfinance Institutions (MFI) and, more broadly, unsecured retail lending as a whole. We have highlighted this earlier, multiple times. However, that is unlikely to affect the large private banks. It simply doesn’t move the needle for them. Giving out MFI loans means taking more risk without getting any returns for it, because the absolute size of the whole industry is negligible. Moreover, it requires special underwriting abilities that NBFCs or mid-sized SCBs are better able to handle.

Therefore, you won’t see how bad the situation is on that front just by looking at the larger private banks. We’ll probably touch it again in the coming stories.

Back to the big banks. In the fourth quarter of FY25, all three banks maintained low bad-loan ratios, with non-performing assets at or near multi-year lows.

HDFC Bank’s gross NPA ratio was 1.33% as of March-end, improving from 1.42% in the previous quarter. This is a slight uptick from 1.24% a year ago — partly because of its recent merger with HDFC Limited — but still very much under control. Net NPAs, meanwhile, stood at a mere 0.43%.

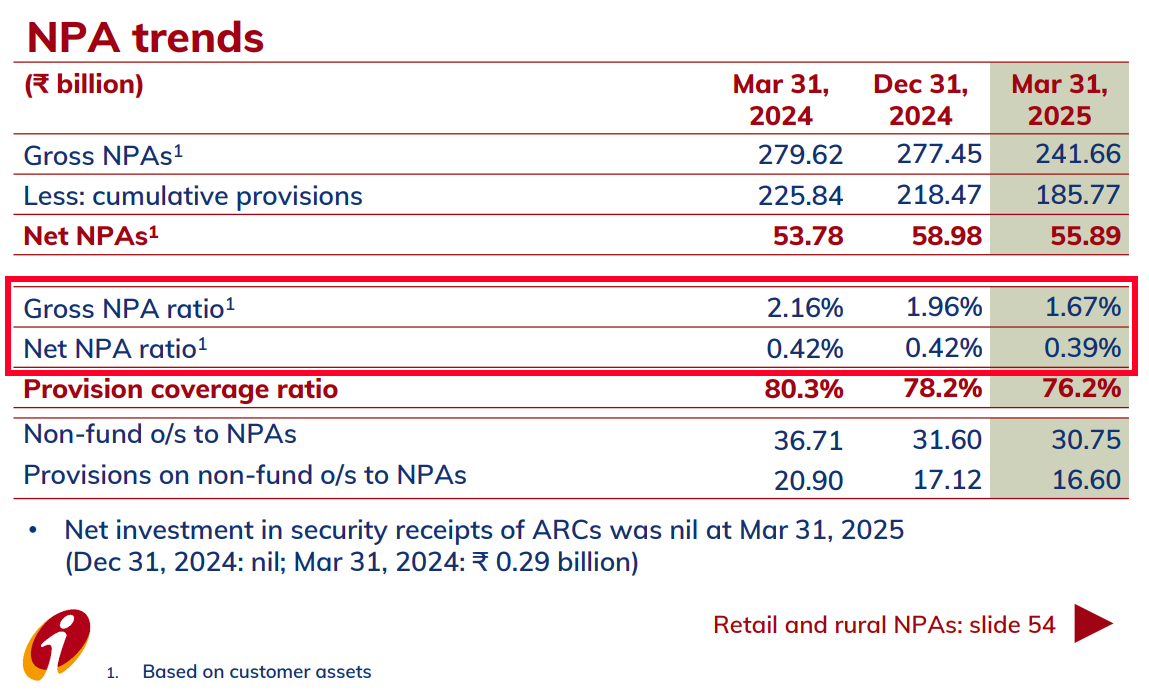

ICICI Bank showed an even cleaner book. Its gross NPAs at 1.67%, down from 1.96% in Dec 2024, and net NPA improving to 0.39%.

Axis Bank was in the same league. Its gross NPAs fell to 1.28% by Q4, from 1.43% a year earlier. Its net NPA was just 0.33%.

In short, these banks have minimal bad loans and mostly falling marginally, which reflects prudent lending with minimal incremental slippages and strong recovery efforts or writeoffs.

The three also seem resilient before future shocks. All three have hefty provision cushions against any future credit hiccups. Axis Bank, for instance, holds total provisions amounting to 157% of its gross NPAs – showing a conservative stance. Meanwhile, credit costs remained low this quarter, and in HDFC Bank’s case actually dropped sharply year-on-year.

For the average banking customer or investor, this stability in asset quality is reassuring: the big private lenders are navigating a low point in the credit cycle with hardly a scratch.

Growth is facing the big slowdown

There’s some slightly less buoyant news, though.

When it comes to growth, Q4 FY25 was markedly slower than the boom a year prior. This was expected – across the industry, credit growth had cooled to about 11% by March 2025, down from ~16.5% the previous year. This came from a combination of factors: softer demand in certain loan segments, as well as an intentional moderation by banks, to bring down their high loan-to-deposit ratios.

This could continue for a while. Motilal Oswal predicts system-wide credit growth will remain tepid at roughly 12% in FY26. In this environment, the top private banks still grew, but mostly in single digits to low teens, a far cry from the 15–20% expansions they enjoyed historically.

HDFC Bank in particular stood out for its subdued loan growth. The bank’s total advances inched up only 7.7% year-on-year. This is an unusually low growth rate for HDFC Bank, which typically sees mid-teens growth.

In its earnings call, the bank pointed to this as a side effect of digesting its merger with HDFC Ltd. The merged entity’s loan-to-deposit ratio was simply too high, and they had to cut down on giving loans so they could bring their books in order. Its management had telegraphed this slowdown as they focused on rebalancing after the merger. Indeed, HDFC Bank pivoted to deposit collection over lending in the near term. Its deposits swelled by about 16% YoY (average basis) in Q4, far outstripping credit growth.

The bank aimed at improving its credit-to-deposit (CD) ratio and replacing expensive borrowings over this quarter. It has largely succeeded in this, bringing its CD ratio down and building a war chest of deposits for future lending.

Meanwhile, ICICI Bank managed to keep its growth engine humming better.

Its domestic loan book grew 13.9% YoY – one of the strongest in the sector. This robust performance was driven by a balanced mix of retail and corporate lending, although corporate lending grew at a notably faster pace — particularly on the back of a robust SME portfolio. It continued to gain market share, even as its deposits rose in tandem by 14% YoY, ensuring no funding crunch.

The bank’s CASA (current and savings account) deposit base dipped slightly to 38.4% of total deposits, which may have marginally raised its funding costs. All in all, though, ICICI didn’t sacrifice growth, delivering double-digit expansion even in a slower market.

Axis Bank’s performance was much more muted. It posted 8% YoY growth in net advances, with total loans at about ₹10.4 lakh crore. This was, however, a deliberate choice. Axis’s management admitted they prioritized margins and quality over chasing growth in FY25’s challenging environment.

The bank still grew selectively. On the one hand, for example, its SME lending jumped 14% YoY. On the other hand, however, retail loan growth was modest at 7%, while Axis’s large corporate book grew 8%. Its borrowing became slightly cheaper, though: Axis managed to increase its CASA ratio to 41% this quarter (from 39% in Q3) by boosting current account balances. Still, like others, a lot of its new deposits were in term deposits, as customers flocked to higher interest rate products – a trend seen across the industry.

Summing up the growth picture: loan growth has downshifted for these banks compared to last year’s highs, but deposit growth has picked up. The focus this quarter was clearly on fortifying the deposit base – even if it meant paying up for term deposits – to support future lending. This dynamic of deposits outpacing loans is likely temporary; as interest rates stabilize, credit growth is expected to regain some pace in the coming quarters.

As per the management of HDFC Bank, for instance, the current credit cycle has bottomed out. The impact of this will show up in the numbers soon — in slightly elevated NPAs and higher credit costs — but things will pick up again:

“If you listen to our Chief Credit Officer, he has done various analyses to say that the credit cycle bottomed out maybe even three quarters ago, four quarters ago and … at the industry level, the nonperforming loans going up and the credit cost beginning to go up.”

Margins are a Balancing Act

With the interest rate cycle turning, net interest margins (NIMs) have become a key area to keep an eye on.

Back when the RBI was hiking rates, banks enjoyed expanding margins, because loan rates rose faster than deposit costs. But now that rates have already been cut, and there’s the prospect of even more rate cuts on the horizon, we’re seeing the opposite. Bank margins are under pressure. Why? See, loans are often linked directly to the policy rate. A cut immediately shows up in the interest borrowers pay. Banks take time to reflect these cuts in what they pay depositors, however. In the interim, their margins take a hit.

Still, in Q4 FY25, the big private banks saw mixed margin trends – margins were broadly stable against the prior quarter, but a tad lower in some cases compared to a year ago.

HDFC Bank, for instance, reported a NIM of 3.73% for Q4. This is roughly flat, sequentially, but slightly below the bank’s historical levels — which used to be comfortably above 4%. This dip is understandable, though: the sudden inclusion of a large home loan portfolio, courtesy of the merger, and an increase in high-cost deposits have diluted its margins.

The bank thinks margins may remain in this range in the near term, especially if there are rate cuts. About 70% of HDFC’s loan book is linked to external benchmarks, so a drop in repo rate would quickly transmit to lower lending rates.

ICICI Bank, on the other hand, managed to hold its margins at elite levels. It posted a NIM of 4.41% for Q4 — essentially unchanged from 4.40% a year ago, and even up versus the prior quarter. ICICI’s ability to sustain such high margins in this climate is notable. It’s helped along by its high CASA share and a focus on risk-adjusted pricing.

The management noted that after peaking around 4.5% last year, ICICI’s margin has moderated to the low-4% range in FY25. It’s likely to operate in that band, going forward, as the rate environment normalizes. In other words, we shouldn’t expect further expansion in NIM, but a sharp decline is not on the cards either.

Axis Bank’s NIM came in at 3.97% for Q4. This was a mild compression from 4.06% a year earlier, reflecting the higher cost of funds — given that Axis raised a lot of term deposits at high rates over the year. However, it was slightly better sequentially — Q3 margins were at ~3.93% — indicating some stabilization.

With CASA improving at the end of the year and excess liquidity in place, Axis could see a little margin support. But like the others, it will be balancing deposit costs carefully.

Right now, it’s hard to keep margins low. Industry-wide, depositors are looking for higher rates. They’re shying away from regular accounts that pay low interest. System CASA growth has been a “challenge” as per analysts – and this will keep banks on their toes to protect margins. Analysts believe that margins will remain under pressure in the first half of FY26 — especially if, as expected, the RBI starts cutting rates. There’s some relief from a recent cut in CRR (cash reserve ratio) requirements and adjustments to lending rates, but by and large, NIMs are currently being squeezed between declining asset yields and still-elevated cost of funds.

The good news is that despite these challenges, all three banks are still operating with healthy spreads and profitability. Their return on assets remains around 1.7–2%, and they’ve managed to absorb higher interest costs without much dent to earnings.

Guidance and outlook

Looking ahead, management commentaries and analyst previews suggest a tone of cautious optimism for FY26. The sector won’t skyrocket, but it’s still in a good spot. The broad themes for the sector are: moderate growth, stable asset quality, and careful margin management.

HDFC Bank’s leadership, for example, has indicated that the bank aims to rev up credit growth to at least match industry average in FY26, and then exceed it in FY27. It’s holding back on growth for now, as it gets its house in order following the merger. But this is a clear signal that, post-merger digestion, it will reclaim its growth momentum. This is consistent with what they have been saying since the beginning, something that we covered too.

The bank spent much of FY25 strengthening its deposit base — but with that task done, it can now lean into lending again.

ICICI Bank, on the other hand, had no trouble growing in FY25. It’s expected to continue on its trajectory. While the bank hasn’t given explicit numeric guidance — they typically don’t — the general vibe from its earnings call was that they see opportunities to grow both retail and corporate books in a “risk-calibrated” way, and they remain confident in expanding their deposit franchise to fund this.

Axis Bank’s CEO struck a candid note in the press release:

“The Bank prioritised profitability over growth, considering the uncertain macros and tight liquidity environment dominating most of FY25, while continuing to meaningfully invest in making the franchise more sustainable.”

But as conditions improve, Axis expects to drive both growth and profitability in FY26. This could mean Axis will aim to push its loan growth back into double digits, perhaps catching up with the industry average.

In all, Q4 FY25 showed that India’s big private banks can deliver steady results even in a “downshift” quarter. They’ve kept asset quality rock-solid, protected margins as best as possible, and adjusted their growth strategies to the new normal. None of the major indicators are flashing red. That probably means we’ll likely be reading about healthy, if not spectacular, numbers from HDFC, ICICI, and Axis in the quarters to come.

CNG is losing its spark

If you look at gas companies’ Q4 FY25 results recently, you’ll see a pattern. There’s a simple but crucial tug-of-war between demand and supply that’s visible all through India’s CNG sector.

Consider this: Adani Total Gas reported a 7.9% decline in net profit to ₹155 crore, even though its revenue climbed 15.5% to ₹1,453 crore. Indraprastha Gas Ltd profit fell 8.8%, although its revenue from operations grew around 10%

These results show an interesting contradiction. Basically, even as these companies are bringing in more revenue, their profits have taken a big hit. Essentially, in the space of just one year, their margins have taken a terrible hit. And this possibly signals a broader trend in the years to come: where gas increasingly takes a back seat, at least as a fuel for vehicles.

So what’s going on here? Let’s break it down.

CNG: the clean fuel alternative

First, the basics: what exactly is Compressed Natural Gas?

Simply put, it's natural gas — mostly methane — that's compressed until it takes up less than 1% of its standard volume. This compressed gas is then used as fuel in vehicles with engines designed to run with the gas. That's what powers all those green-stickered autos, taxis, and increasingly, private cars you see on the road.

CNG gained popularity in India for three reasons.

First, it's much cleaner than conventional fuels. This made it an attractive solution for cities struggling with air pollution, most notably Delhi, where a 1998 Supreme Court ruling mandated all public transport vehicles switch to CNG.

Second, at least so far, CNG has been substantially cheaper than petrol and diesel, which makes it a lot more attractive to regular consumers. At its peak, running a vehicle on CNG could save drivers 30-35% compared to petrol. Even in early 2025, despite recent price increases, CNG still offers savings of about 25-30% over petrol.

Third, government policies actively promoted CNG adoption. Governments didn’t limit themselves to following court mandates, but went beyond — expanding infrastructure and keeping prices lower through gas allocation policies. This made it easier for consumers to make the transition to CNG.

These factors came together to fuel remarkable growth in CNG usage. India's CNG vehicle fleet is predicted to have reached 7.5 million vehicles by the end of FY 2025 — three times more than a decade ago, in FY 2016. CNG stations too increased rapidly — from about 1,000 in FY 2016 to over 7,400 today.

As demand for the fuel grew, the options of CNG-fueled vehicles grew as well. A few years ago, you might have had just a handful of CNG car models to choose from. Today, there are over 30 CNG variants across multiple manufacturers, giving consumers plenty of choices when shopping for a cleaner ride.

Things will probably continue on this trajectory. Experts believe CNG use in India will keep growing in the coming years. In fact, they think CNG adoption will likely increase by nearly 60% by 2030.

So more and more people are using CNG. Gas companies have clearly unlocked a major source of demand. Where is the problem, then? Why are their earnings falling?

The Supply Side: APM Allocation

On the other side of demand is supply. And this is one place where the government has traditionally played a huge role — through its Administered Price Mechanism (APM) for gas allocation.

But lately, the government is beginning to pull away from managing supplies — and that threatens to throw the market into disarray.

What's APM gas? Essentially, the government pushes domestic natural gas from fields operated by state-owned companies like ONGC to private companies, at below market prices. This gas has historically been the backbone of India's CNG ecosystem, as it allows these companies to offer CNG at attractive prices to us consumers. This is the mechanism that underwrote India’s boom in CNG vehicles.

But here's the problem: the government’s gas fields are growing older, and they’re beginning to empty out. Production from these aging fields is declining at 9-10% annually. And they haven’t found new sources to draw gas from.

As supply falls, something has to give way. That’s what we’re starting to see.

In October 2024, the government cut the allocation of APM gas to city gas distributors from 68% to 51%. In November, it was cut further to 37%. Even though the allocation increased slightly in January 2025, if we compare it to what was available before October, the overall allocation of APM gas has fallen drastically.

What happens when CNG suppliers don't get enough cheap gas? They're forced to buy more expensive alternatives — either imported liquefied natural gas (LNG), or gas from newer domestic fields that costs nearly twice as much.

Let’s put in some numbers to give you a clearer picture. APM gas prices have been fixed at $6.75/MMBTU. This fixed price also increased from $6.50 to $6.75 only recently. Meanwhile, alternatives cost $10-14. Basically, if gas retailers move from APM gas to what’s available on the market, their costs could double overnight.

This price difference puts CNG retailers in a tough spot. Companies like Indraprastha Gas, Mahanagar Gas, and Adani Total Gas face a difficult choice: they can either absorb the higher costs, making it less attractive to buy, or pass them on to consumers. So far, they've done a bit of both—implementing modest price hikes of ₹1-3 per kg while also taking a hit to their margins.

Increasing prices by too much reduces the biggest advantage of CNG — its affordability. The very reason people moved to CNG over petrol and diesel was its lower prices. But now, with supply drying up and prices increasing, can that demand sustain?

Why can't India just import more gas?

You might wonder: If domestic gas production isn't keeping up with demand, can't India just import more natural gas to fill the gap? After all, isn’t that what many other countries all over the world do?

Well, it's not that simple.

See, the easiest way to transport gas from place to place is to set up big pipelines, and have it flow naturally. But that isn’t an option India has. There are simply no gas pipelines connected to India.

Instead, we have to try something much harder: we have to bring it over in ships. But gas, in its regular form, would take too much space on a ship. So, it has to be cooled and turned into a liquid at the exporting country, and then shipped over.

When the ship arrives, the gas is warmed again and turned back into gas at stations near the ocean. Only then can it be transported from coastal areas to inland cities through pipes and trucks.

This isn’t an easy process. And it makes imported LNG far more expensive than what we produce in India — often two to three times the cost of domestic gas. If CNG retailers had to rely entirely on imports, they'd need to raise prices by a lot, basically wiping out CNG's price advantage over petrol and diesel entirely.

Moreover, if you want to import gas from abroad, you need certainty — because arranging LNG shipments takes weeks or even months of planning. Sadly, with the way gas policy is currently determined, that certainty is in short supply. Domestic gas allocations can be cut without warning. And if they do, there's no quick way to arrange imports to keep all CNG stations fully supplied.

Basically, short of building a new international pipeline (and there are some already in the works), there’s no easy way of importing the gas we need for cheap.

The supply crunch gets worse

Ultimately, there are many long-term problems with our CNG supply chains:

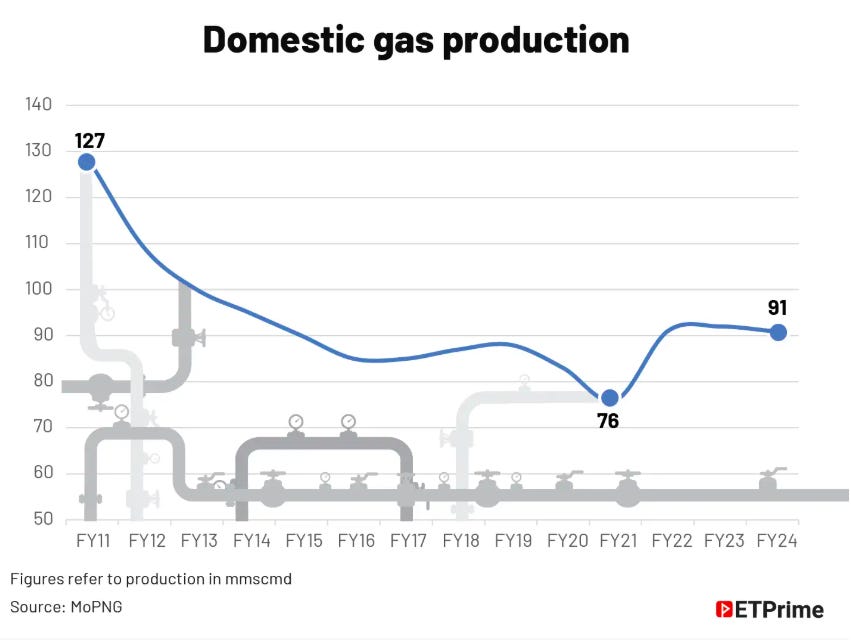

Stagnant domestic production: India's natural gas production has barely increased over the past decade — rising just about 3%, even while consumption jumped 30%. ONGC and other producers are struggling to find and develop new fields quickly enough to offset declines in aging ones. Domestic production covers hardly 50% of domestic demand. This is why the APM system is now in jeopardy.

Infrastructure bottlenecks: Even though India is currently one of the world’s most prolific builders of gas infrastructure, India's gas pipeline network still has weak spots. In May, for instance, a major pipeline issue in Pune caused a days-long CNG shortage, with over half the city's CNG stations running dry. Drivers waited in line for hours at the few stations that had gas.

Prioritization of other sectors: As gas supply gets worse, the government has a tough choice: how does it distribute the limited gas it has, between household piped gas, industries that need it as raw material, and CNG for vehicles? In practice, vehicles are lower down its ladder of priorities. This policy choice has meant that transportation fuel feels the pinch first when supply tightens.

Seasonal and regional variations: During high-demand periods or in areas far from gas sources, supply constraints become more obvious. Some regions see frequent low-pressure issues at CNG stations. Simply put, CNG stations need gas to come in with strong pressure, and when supply drops, there isn't enough gas pressure in the pipes reaching those stations. And so, when there’s low supply, even the little gas which remains becomes much harder to distribute.

Our neighboring countries seem to be facing similar issues. Pakistan, for example, faced such severe gas shortages that many CNG stations were completely shut down for months. Similarly, Bangladesh had to impose daily closures of CNG stations for several hours to conserve gas for other uses.

For India, the shortage hasn't reached such extreme levels yet, but there are warning signs. In some cities, CNG stations have seen longer queues as pumps operate at reduced capacity. Occasional supply disruptions have left drivers helpless and looking for stations with adequate gas.

The Road Ahead

Despite these problems, most industry analysts remain cautiously optimistic about CNG's future in India. The government still aims to increase natural gas's share in the energy mix from 6.5% to 15% by 2030, and CNG is expected to play an important role in this transition.

However, the days of CNG’s massive price advantages over conventional fuels may be fading. The future of CNG depends on many factors, but at its core, it simply depends on the balance between two things that governs almost everything — demand and supply. And there, an equation that held for over a decade is now falling apart.

Tidbits

Industrial Growth Recovers Slightly to 3% in March, FY25 Expansion at 4%

Source: Business Standard

India’s Index of Industrial Production (IIP) rose by 3% in March 2025, up from 2.72% in February, marking a mild recovery after a six-month low. Despite this uptick, full-year industrial growth for FY25 stood at 4%, the weakest in four years and notably lower than the 5.9% recorded in FY24. Within segments, consumer nondurables saw a 1.6% contraction for the year, deepening to 4.7% in March—the fourth consecutive monthly decline. Consumer durables grew 7.9% annually and 6.6% in March, driven by sectors like electronics. Infrastructure goods expanded 6.6%, capital goods 5.5%, while primary and intermediate goods grew 3.9% and 4.1% respectively during the year. March’s overall industrial output was supported by a 6.3% rise in electricity and 3% growth in manufacturing, though mining growth remained subdued at 0.4%.

Adani Green Energy Reports 59% Profit Growth in FY25, Driven by Greenfield Capacity Additions

Source: Business Line

Adani Green Energy Limited posted a 59% year-on-year rise in net profit to ₹2,001 crore for FY25, supported by significant greenfield capacity additions of 3.3 GW across Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Andhra Pradesh. The company's total income grew 18% to ₹12,422 crore, while revenues from power supply rose 23% to ₹9,495 crore. Operational capacity expanded by 30% year-on-year to reach 14.2 GW, with an additional 1 GW nearing completion. Energy sales increased by 28% to 27,969 million units during the year. At the Khavda project in Gujarat, Adani Green operationalised 4.1 GW of solar and wind capacity within two years of breaking ground. The company reported a solar capacity utilisation factor (CUF) of 32.4% in Q4 FY25 and achieved water positivity across its operational portfolio ahead of its FY26 target.

Delays in Machinery Imports from China Threaten Apple's India Production Expansion

Source: Business Standard

Apple Inc’s plans to expand its iPhone production in India face challenges as delays in importing crucial machinery from China could impact the launch of the iPhone 17 and the company's broader production goals. In FY25, Apple exported iPhones worth ₹1.5 lakh crore from India, with about 20 per cent of these exports heading to the US. The company’s ambition is to increase production capacity to $26–27 billion by FY26, aiming to meet the $40 billion US iPhone demand directly from India. Currently, India is expected to account for 25 per cent of Apple’s global iPhone production value by FY26. Vendors like Tata Electronics and Foxconn are building new capacity to support this shift, while Indian engineering firms are working to localize the production of critical machinery. However, continued import delays could jeopardize these plans and slow India's rising share in global electronics manufacturing.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Prerna.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Can compressed biogas be the solution?

very nice hehe