The Flip Side of Easy Loans in India

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s Unsecured Loan Boom: A Risky Trend?

Why Zomato’s Profits Took a Hit

India’s Unsecured Loan Boom: A Risky Trend?

In December 2024, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) released its Financial Stability Report. This report essentially gives us an overview of how stable the Indian financial system is, covering banks, capital markets, and insurance.

A couple of weeks ago, we talked about the main highlights of this report— But there’s one aspect we didn’t dive into last time, which is particularly interesting for investors: the lending and borrowing trends in India.

One key point the RBI’s report highlights is that household debt is rising. In simple terms, more people are taking loans now than before. But what’s even more intriguing is the difference between the kinds of borrowers and the reasons they’re taking these loans.

To understand this better, imagine two groups of borrowers.

The first group includes people with strong credit scores. These borrowers typically take loans to buy homes, start or expand businesses, or invest in assets that can grow in value over time. In short, they’re borrowing money to create something valuable.

The second group includes people with weaker credit scores. These borrowers are more likely to take personal loans to spend on consumption or meet short-term needs.

This divide between loans for creating assets and loans for consumption is catching people’s attention because it might be an early warning sign of trouble for the wider financial markets.

One way lenders assess this potential trouble is by using a metric called Portfolio at Risk (PAR). Simply put, PAR helps lenders track loans that haven’t been repaid on time.

For example, PAR 30-90 refers to loans overdue by 30 to 90 days, while PAR 90-180 refers to loans overdue by 90 to 180 days, and so on. If the number of overdue loans starts to rise, it’s a sign that more borrowers are struggling to repay what they owe, which could spell trouble for the financial system.

A report from the credit bureau CRIF sheds some light on this situation. As of September 2024, the total outstanding personal loans in India stood at ₹13.7 lakh crore. Of this, public sector banks hold the largest share, about 38%, followed by private banks with 33%, and NBFCs (non-banking financial companies) with around 24%.

Lately, there’s been a big shift in who is giving out new loans. NBFCs, in particular, have grown their share of new loans to 38.7% in the first half of this financial year, compared to 33.2% during the same period last year.

CRIF also studied small-ticket loans, ranging between ₹10,000 and ₹50,000, and found some concerning trends. Nearly 29.3% of people who took these loans in December 2023 saw their credit scores drop within six months.

What’s more troubling is that these borrowers kept taking more loans—62.7% more, to be exact—and the total amount they borrowed went up by 37.6%. In simple terms, they kept piling on debt even as their credit scores were falling. That’s risky because if someone’s financial health is already weak, borrowing more money only makes it harder for them to repay, increasing the overall risk in the system.

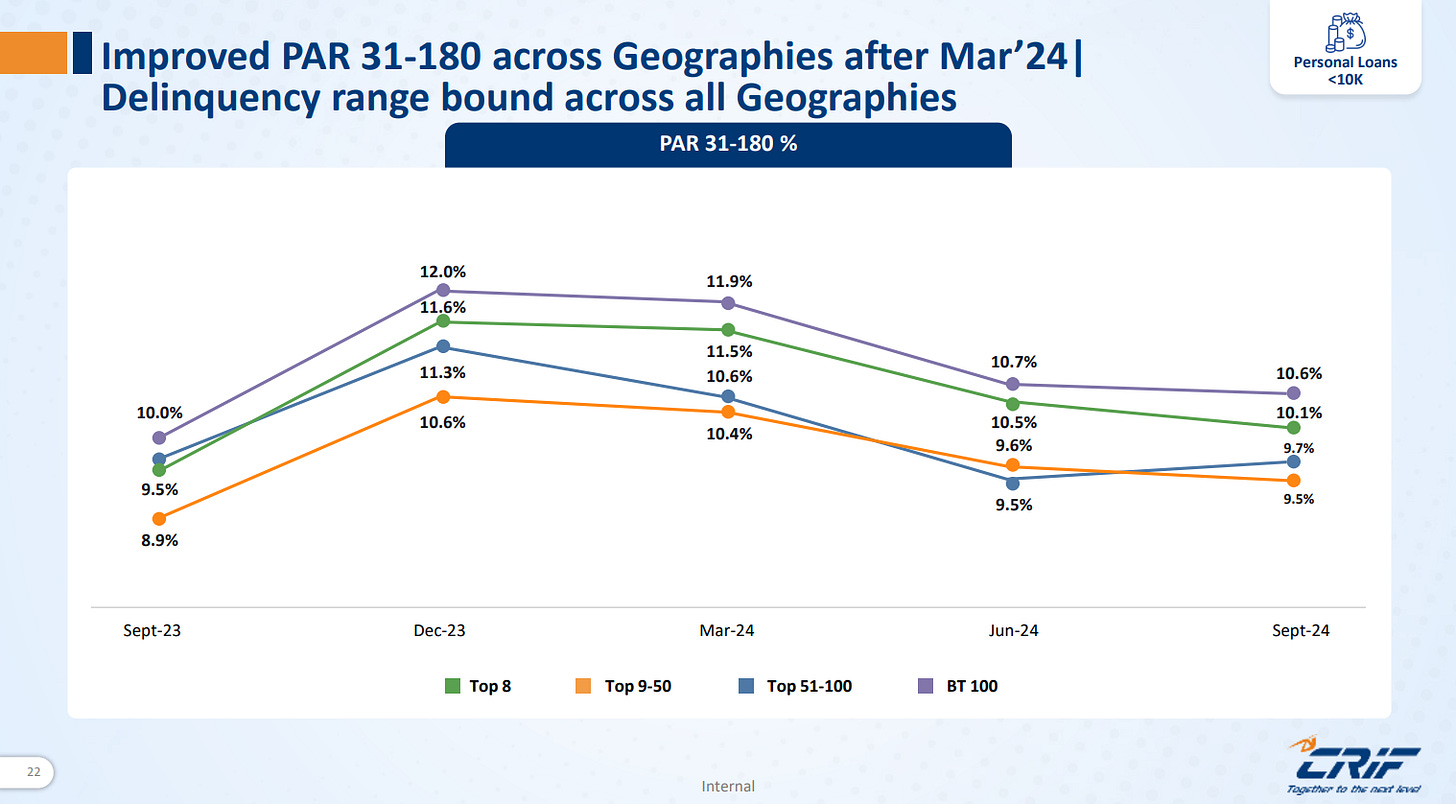

Where these borrowers live also matters. According to CRIF, while the top eight major cities in India show some signs of stress in loan repayments, the situation is much worse in smaller cities. In cities ranked 51 to 100, the percentage of overdue loans in the 31-to-180-day range (PAR 31–180) jumped from 6.8% to 8% in just one year.

What’s surprising is that NBFCs are actually stepping up their lending activities in these smaller markets, even though the risk of defaults there seems to be rising.

When it comes to the smallest-ticket loans—those under ₹10,000—NBFCs dominate the market with a massive 94% share.

In just six months of FY25, 4.63 crore new loans were issued in this category. But this is also where the most stress is showing. The number of loans overdue by more than 360 days (PAR 360+) has shot up to 39.7%, compared to 24.5% the previous year.

What’s even more concerning is how quickly these loans are going bad. Many borrowers start facing repayment issues just eight to ten months after taking the loan, much faster than in other types of loans.

Now, if we shift our focus to unsecured business loans, the picture is a bit different but still worrisome. This segment has grown by 43.5% over the past year, reaching a total of about ₹7.8 lakh crore. While that growth sounds impressive, the delinquency rates—loans not being repaid on time—have been steadily rising, especially in smaller cities.

The most puzzling part of all this is that these red flags are popping up even as the broader Indian economy seems to be doing reasonably well.

Despite some positive indicators, certain areas of the retail lending market are showing signs of stress. This raises important questions: Are people in these segments taking on more debt than they can afford? Or are lenders taking on too much risk in their push for growth?

For investors and anyone tracking the markets, the key question is: what should we be paying attention to in the coming months?

First, regulators might tighten the rules further on unsecured loans. The RBI has already taken steps by increasing risk weights and urging banks to slow down their retail lending and partnerships with fintechs offering unsecured loans.

Second, NBFCs could become more cautious, especially in smaller cities, and rethink their lending strategies.

And finally, we need to watch if these riskier trends stay limited to specific segments or if they start spreading to other parts of the lending market. Recent results from Axis Bank and L&T Finance show that loan growth is uneven across different segments, which adds to the complexity of the situation.

At the core of all this is a bigger question: how safe or risky are India’s current lending practices?

Are some borrowers taking on more loans than they can realistically repay? And are some lenders chasing growth so aggressively that they’re overlooking the financial health of borrowers?

These are critical questions, and the answers affect everyone—whether you’re a borrower, an investor, or someone analyzing the economy or the markets.

The data we have right now suggests that the answers may not be entirely reassuring. That’s why this is an area we all need to keep a close eye on.

Why Zomato’s Profits Took a Hit

Zomato’s latest results are out, and there’s been quite a bit of buzz about them. So, let’s break down what happened this quarter.

Zomato reported consolidated revenue of ₹5,746 crore, which is a solid 58% jump compared to last year and a 12% increase from the previous quarter.

This growth came from both its core food delivery business and Blinkit. But here’s what didn’t sit well with the markets: their net profit dropped to ₹59 crore, down from ₹176 crore in the previous quarter and ₹138 crore a year ago.

So, why did profits take a hit?

The short answer: Blinkit’s rapid expansion weighed on their margins. They invested a lot in opening 368 new dark stores, bringing Blinkit’s total to 1,007 stores.

For those who might not know, dark stores are small warehouses set up in neighborhoods to make those super-fast deliveries possible. They’re stocked with everyday essentials like groceries, snacks, and beverages so orders can be picked, packed, and delivered in minutes. But here’s the catch—dark stores are expensive to set up and operate, especially in the beginning when order volumes are still low.

As CFO Akshant Goyal explained, “The percentage of stores that are not mature is increasing, and as a result, utilization is falling. This is why profitability has taken a hit.”

In simple terms, opening more stores means taking on higher upfront costs—like rent, salaries, and operational expenses—before those stores start making enough money to cover their costs.

But dark stores are just one piece of the puzzle. Zomato has also been building larger warehouses. Unlike dark stores, warehouses act as central hubs where bulk inventory is stored before being sent out to dark stores. As Akshant Goyal put it, “New warehouses take longer to ramp up than new stores, and hence are even more margin-dilutive in the short term.”

Translation: Warehouses are more expensive, and they hurt profit margins even more, so losses will stick around for now.

Blinkit’s 1,007 dark stores put it ahead of Zepto’s 700–750 stores and Swiggy Instamart’s roughly 600. But the competition isn’t standing still. Zepto is aiming for 1,200 stores by March 2025, and Swiggy Instamart is targeting 1,000 stores.

Meanwhile, Blinkit’s average order value (AOV) is ₹707 this quarter, which is much higher than Swiggy Instamart’s ₹499 and Zepto’s ₹550.

Customer retention is also holding up well. Blinkit’s December 2022 customers have stabilized at around 40% retention, and Gross Order Value retention has crossed 100%. Simply put, the customers who stick around are spending more, which is a good sign for the business.

It’s clear that profitability is still a long way off. Dhindsa acknowledged this, saying, “Our network will likely carry a heavier load of underutilized stores, impacting profits in the next one to two quarters.”

Now, let’s talk about Zomato’s core business—food delivery. Gross Order Value (GOV) for food delivery grew by 2% quarter-on-quarter, reaching ₹9,913 crore.

Adjusted revenue went up by 3% compared to the last quarter and by 17% year-on-year to ₹2,413 crore. Margins are also improving, with adjusted EBITDA climbing to ₹423 crore. That brings food delivery margins up from 3.5% last quarter to 4.3% now.

Management seems optimistic about more progress. “We expect EBITDA margins for food delivery to reach 5% in the next few quarters,” said Rakesh Ranjan, CEO of Zomato’s food delivery business.

That said, growth is slowing. Zomato points to broader economic conditions for this. “Currently, we are going through a broad-based slowdown in demand, which started during the second half of November,” Ranjan explained.

To keep things fresh, Zomato is testing 15-minute food delivery by working with restaurants to speed up preparation times. But this is still in its early stages. Deepinder Goyal shared why scaling this model is tricky: “10-minute deliveries are only feasible with dense kitchen networks and shorter preparation times. Doing this consistently and profitably is not an easy problem to solve.”

Meanwhile, Swiggy is already making strides here—its 10-minute delivery service, Bolt, now accounts for 5% of their food orders.

Zomato seems to be in a transitional phase. Quick commerce is clearly the focus, but it’s a costly gamble, and profitability is still a distant goal. It’ll be interesting to see how things evolve in the coming quarters. Maybe we’ll even hear more about their District App soon.

Tidbits

The National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) has ordered the liquidation of Go First, officially ending its 20-month-long insolvency process. The airline owes ₹6,200 crore to lenders, with its main creditors being the Central Bank of India (₹1,934 crore), Bank of Baroda (₹1,744 crore), and IDBI Bank (₹75 crore). The Committee of Creditors (CoC), which approved the liquidation, has estimated the costs at ₹21.6 crore, to be covered by its members. Go First filed for insolvency on May 2, 2023, after determining that resolution plans were not viable. Separately, the airline is pursuing a $1 billion claim against Pratt & Whitney for faulty engines and has secured $20 million in arbitration funding from Burford Capital.

The Indian government has approved the export of 10 lakh tonnes of sugar for the 2024–25 season. This marks a shift in policy after sugar exports were completely restricted in 2023–24 due to domestic supply concerns. Maharashtra will export the largest share (374,996 tonnes), followed by Uttar Pradesh (274,184 tonnes) and Karnataka (174,980 tonnes). The announcement, however, led to a sharp drop in sugar prices, which fell to a three-year low. Traders were caught off guard, especially since sugar production is expected to fall below consumption for the first time in eight years.

The government has provisionally approved ₹3,516 crore in investments under the third round of the PLI (Production-Linked Incentive) scheme for air conditioner and LED components. This round includes ₹2,299 crore from 18 new companies and ₹1,217 crore from six existing beneficiaries that are increasing their investment commitments. Since its launch in FY 2021–22, the scheme has attracted investments from 84 companies, totaling ₹10,478 crore. These investments are expected to result in production worth ₹1,72,663 crore. With incentives of 6–4% for five years, the initiative aims to increase domestic value addition in these sectors from the current 15–20% to 75–80% by 2028–29.

-This edition of the newsletter was written by Anurag and Krishna

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.