Who said what About India's Stock Valuations, RBI’s Mistake, Ray Dalio’s Debt Warning & More

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

Damodaran says India is an expensive market

Aswath Damodaran—who the internet calls “the dean of valuation” — dropped a big statement on his blog:

What do valuations even mean?

At its core, valuations are a way to measure a company’s “worth”. They tell you whether a stock—or an entire market—is expensive or cheap. To make that call, investors look at metrics like P/E ratio, EV/EBITDA, and EV/Sales. But here’s the dirty little secret: valuations are incredibly handwavy. And stock prices don’t always obey what they say.

There’s no ironclad rule that connects valuations to where the market is headed next. A stock can be expensive and still go higher. A stock can be cheap and stay cheap for years. This is why you can’t time the market based on valuations alone.

Now, are the markets overvalued?

That’s the million-dollar question, right? The short answer—it depends. If you look at India’s market, yeah, it’s expensive based on these traditional metrics. But does that mean a crash is coming? Not necessarily.

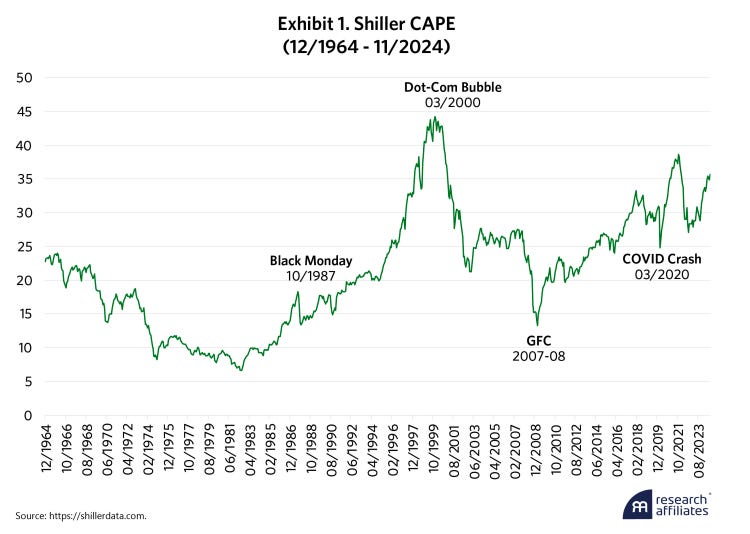

People have been calling the U.S. market overvalued since 2012. The P/E ratio was “too high.” Stocks were “too expensive.” Guess what? The S&P 500 has tripled since then. If you sat on the sidelines because you thought valuations were too high, you missed out on one of the best bull markets in history.

That’s because valuations alone don’t drive stock prices—earnings growth, liquidity, and investor sentiment matters. Here’s a very apt quote from the economist—Keynes:

“Markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Basically, just because something looks expensive doesn’t mean it won’t get even more expensive. And if you try to short the market too early, you might just get blown up in the process.

So, should you even care about valuations?

Yes—but not in the way most people think. Valuations matter in the long run. If you buy a market at insanely high valuations, your future returns will probably be lower. But in the short term? Market sentiment and liquidity run the show.

This is why people who blindly rely on P/E ratios or EV/EBITDA to make investment decisions end up frustrated. These metrics don’t tell the whole story. They’re just one piece of a much bigger puzzle.

Damodaran isn’t wrong—India’s market is expensive. But expensive doesn’t automatically mean crash. It may just mean you need to be smarter about what you own.

Adding to the debate, Dhananjay Sinha, Co-Head of Equities & Head of Research at Systematix Group, in an interview with ET noted that India’s valuations look stretched—especially when you factor in slower earnings growth:

He points out that the Nifty's average earnings growth is hovering around 4-5%, while valuations remain at 20-22 times earnings. This creates a significantly high PEG ratio, especially when compared to the S&P 500. PEG ratio for context is like a reality check for a stock’s PE by factoring in how quickly its profits are growing. Even if a company looks pricey on a P/E basis, strong earnings growth can make it feel more reasonable, while a high PEG ratio warns us that we might be overpaying for slow growth.

What's particularly interesting is Sinha's comparison with the US market. While the S&P 500 is showing earnings growth of around 16% with 77% positive surprises this quarter, Indian markets are seeing more negative surprises. This adds weight to the argument about relative overvaluation.

However, Sinha's perspective adds nuance to the valuation debate. Rather than predicting an immediate crash, he suggests "there can be some more correction before deep value emerges."

In other words, Sinha’s view aligns with Damodaran’s warning: Indian equities might be priced for perfection. But he also cautions that expensive markets don’t necessarily collapse overnight—there are many moving parts, including domestic retail inflows, global liquidity, and broader economic conditions.

Since we are talking about valuations, it would be ignorant of us not to bring up Naren—whose comment last week made everyone in the finance industry go bonkers.

Naren vs small-cap

Last week, We covered what Naren said, and at the time, it felt like just another discussion. But since then, the finance world—especially the Twitter finance crowd—has lost its mind over it. We’re talking about fund managers, analysts, retail investors, and anyone else who is part of Fintwit all weighing in with their takes, counter-takes, and counter-counter-takes.

What Did Naren Actually Say?

In his speech, Naren warned bluntly, “I think this is the most dangerous year after 2007–8,” comparing today’s market risk to that of the crisis years. He stressed that banks are keeping their balance sheets safe and taking almost no risks on the corporate side, leaving all the risk to the investors. “All the risk is being taken by all of you,” he said. He also explained that companies are no longer borrowing from banks—they are raising money directly from investors through IPOs and placements. This shift means that retail investors are now bearing risks that were once managed by financial institutions.

Naren went on to say that a systematic investment plan (SIP) can be a double-edged sword if you invest in the wrong asset class. He warned, “If you invest in a SIP in the wrong product, you are headed for trouble.”

For those already in small and midcap funds, he advised a clear exit: “This is a time to clearly take out money from small and midcap funds… if you start thinking of 2035, you will regret it.” He even pointed out that valuations in these segments are extremely high—citing a median P/E ratio of 43—which only adds to the risk.

It’s important to note that Naren has been warning about these risks for over a year now. Back in early 2024, he was already pointing out that valuations were getting stretched, and by mid-2024, he was cautioning that SIPs in small caps might not deliver the returns many expect. This long-standing message now meets a market buzzing with opinions.

On Twitter, We saw an interesting tweet that highlighted the trend that FII Ownership of Mid-Smallcaps is at All-Time High & that of Largecaps at All Time Low. He then further compared today’s market with peaks seen in 2007, 2010, and 2017.

Amit Mantri, a fund manager, noted that although median small and midcap valuations have dipped slightly compared to seven months ago, they remain at levels never seen before in Indian history.

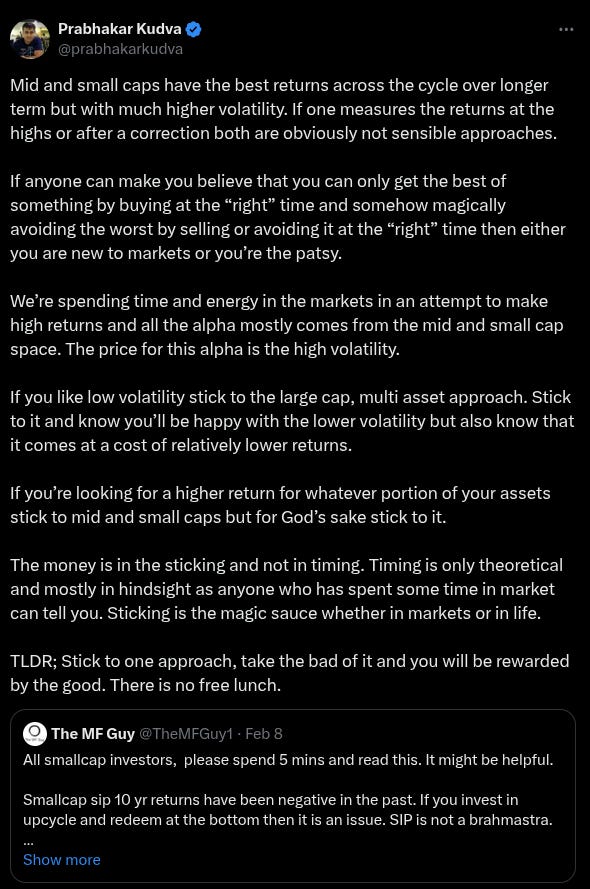

Meanwhile, this tweet from another fund manager, Prabhakar Kudva, pointed out something that contrasts with what Naren said. He said that while timing the market sounds appealing, “if you know when to enter, you’d already know when to exit”—a luxury few actually have.

Adding another perspective, Deepak Shenoy, founder and CEO of Capital Mind, offered a measured counterpoint. He observed that despite all the talk of stopping SIPs in midcaps, a 10–20% dip is normal and should be expected. He cautioned against knee-jerk selling, arguing that “blind selling” isn’t a great idea when market corrections are part of the cycle.

In fact, from his calculations, smallcap funds have even seen net inflows of about Rs 2800 crore in February, following a -10% month in January—a sign that disciplined investors are still sticking to their strategies.

This leads to a critical question for retail investors like us: If a layman follows Naren’s advice on when to exit, who tells them when to enter? If perfect timing were possible, wouldn’t knowing one imply knowing the other? An investor would have to be right twice—both at entry and exit—and that level of precision is something most people simply don’t grasp.

After his video blew up, Naren gave an interview to The Economic Times, where he said, “Don't want to put foot in my mouth again but SIP or lump sum, investing in a costly asset class won't get you value.”

So, where does that leave us? Should we exit or not? We are not experts either, but we’ll put forward this question again: If we follow Naren’s advice on when to exit, who will tell us when to enter again?

Did the RBI Make a Big Mistake with the Rupee?

The former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian made a big statement at an event:

Understanding Exchange Rates

To understand why this is such a big deal, we first need to break down how exchange rates work. The value of the Indian rupee against the U.S. dollar is determined by supply and demand. If more people want dollars (for imports, foreign investments, etc.), the dollar becomes more expensive, and the rupee weakens. Conversely, if demand for rupees rises, its value strengthens.

Most countries follow a flexible exchange rate system, meaning that market forces—rather than government intervention—determine a currency's value. However, central banks sometimes step in to prevent extreme swings that could destabilize the economy.

The Role of the RBI

India’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), traditionally follows a policy of managed flexibility. This means that while the rupee generally moves based on market conditions, the RBI intervenes if things get too chaotic. It can do this by buying or selling dollars to influence the rupee's value.

For example, if the rupee is falling too fast, the RBI can sell dollars and buy rupees, making rupees scarcer and supporting its value. On the other hand, if the rupee is getting too strong, the RBI might buy dollars and release rupees into the market, ensuring that the currency doesn’t appreciate too much.

The Controversy: Did the RBI Peg the Rupee?

A few weeks before his statement, Subramanian, along with the economists Josh Felman and Abhishek Anand, published an article in Business Standard arguing that the RBI had abandoned its traditional flexible exchange rate policy and unofficially pegged the rupee to the dollar. They pointed out that from 2022 to early 2025, the rupee was surprisingly stable, even when global conditions suggested it should have weakened more significantly.

Felman, Anand, and Subramanian argue that the RBI kept the rupee artificially strong by repeatedly selling dollars, preventing it from depreciating. While this made imports cheaper and controlled inflation, it had a negative impact on Indian exports, making them less competitive in global markets.

They also highlighted the rise in external commercial borrowings (ECBs)—loans taken by Indian companies from foreign lenders.

Their argument was that the RBI’s actions created an environment where borrowing from abroad became more attractive than borrowing domestically. When the RBI keeps the rupee artificially strong, it makes foreign loans cheaper for Indian companies because they expect to repay them at a stable or stronger rupee rate. This led to a sharp rise in foreign borrowings, with Indian firms increasingly opting for external loans instead of taking credit from domestic banks.

This became a concern because higher foreign borrowing increases India’s vulnerability to exchange rate risks. If the rupee were to suddenly weaken, these companies would face higher repayment costs, which could strain corporate balance sheets and put pressure on the overall economy.

The RBI’s Response: Preventing Chaos, Not Pegging

RBI a while back had released a report on this. Pranav from the team had written about this a while back on this:

In a recent paper, though, the RBI pushes back against this narrative.

It claims that markets don’t always reflect any deeper fundamentals about an economy. Many short-term factors can distort prices. In particular:

Foreign portfolio investors often invest with short time horizons and buy or sell something based on momentary price movements. This creates a substantial amount of volatility — as large sums of money can enter or leave a country overnight.

In times of excessive market froth, speculators bring a lot of “hot money” to currency markets, making bets that don’t reflect underlying trade activity.

These sources of money are temporary and volatile, and mess up the ‘real’ prices of a currency. To the RBI, these affect currency prices much more than a country’s actual economic condition.

The SBI Research Report: A Different Perspective

A report from SBI challenges some of the claims made by Subramanian, Felman, and Anand. One key argument from their side is that the RBI’s policies encouraged Indian firms to borrow more from foreign markets instead of domestic banks, increasing India’s external commercial borrowings (ECBs).

According to their analysis, some of the borrowing figures used in these claims included foreign investments in Indian bonds, which are not the same as corporate loans. This means that the reported surge in ECBs may not have been as dramatic as Subramanian and his colleagues suggested.

So, what’s the truth? Hopefully, we get to know soon because we are clueless.

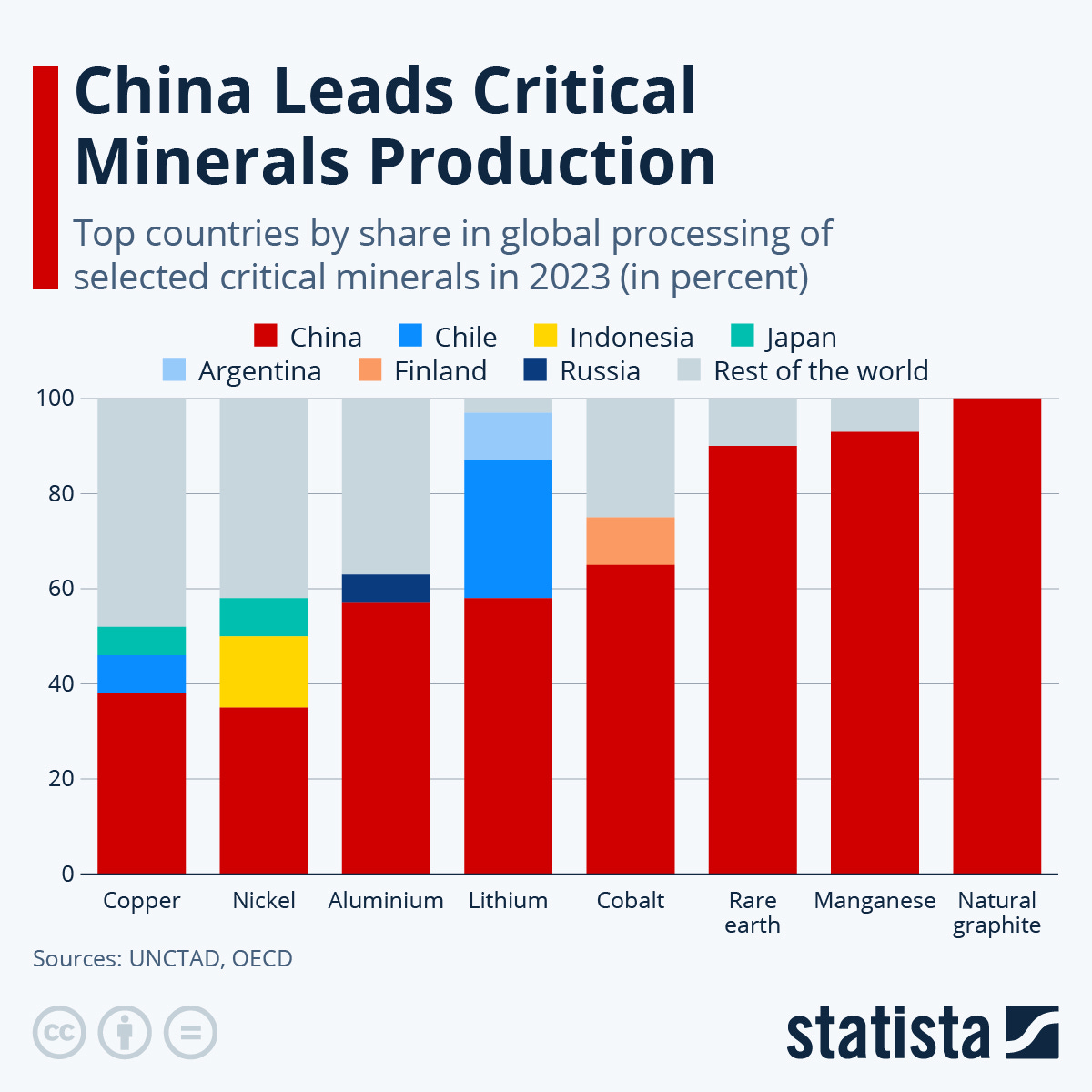

Is there no such thing as critical minerals?

Javier Blas is a well-known Bloomberg Opinion columnist who focuses on energy and commodities. He’s also the co-author of “The World for Sale,” which dives deep into how global resource trading really works.

In his recent piece, Blas talks about a handful of metals that many refer to as “critical minerals” but that he prefers to call “minor metals.” There’s one particular line where he notes how the term “critical minerals” can be great for a company’s image — or “a lot sexier,” as he puts it — especially when firms want to boost their share prices. By branding them as critical, there’s an aura of urgency and importance that can be appealing to investors, even though the overall market size of these metals is relatively small.

What are critical minerals?

So, what exactly are these “critical minerals” or “rare earth metals” everyone’s been so worked up about? These terms refer to metals and minerals that play specific and often vital roles in modern technology. They can be essential for manufacturing smartphone screens, solar panels, certain types of ammunition, or specialized steel alloys.

The tricky part is that, from one nation’s perspective, these metals might be crucial to national security or industrial strategy, while for another country, they might not be so significant at all. In other words, “critical” can be more of a geopolitical or strategic label than a reflection of real scarcity or economic impact.

Blas urges readers not to buy into the hype around China’s moves to impose export controls on these minor metals. He provides context by looking at the dollar value of US imports and showing that, on a macro scale, the sums involved are actually very small.

Even if prices were to rise or China was to restrict exports further, Blas argues that alternative sources, recycling, or engineering solutions would probably step in to fill any gaps. In short, it’s unlikely to topple the US economy or paralyze major industries — a stark contrast to the dire headlines we sometimes see.

Why is this myth of “critical minerals” so persistent, then? Partly, it’s because industries and governments toss around terms like “rare” and “critical” to emphasize their own strategic priorities.

Another factor is that the global supply chains for these metals can indeed be concentrated, often in China. This concentration does create geopolitical leverage. But as Blas says, it’s easy for people to sensationalize supply constraints and overlook the fact that many of these markets aren’t large enough — in dollar value — to deliver the knockout punch some fear.

Ultimately, Blas offers a reality check: just because a resource is called “critical” or “rare” doesn’t mean it’s poised to trigger a national crisis if one big exporter changes the rules. Yes, countries should pay attention to supply chains, foster domestic production where it makes sense, and invest in recycling and alternatives.

Understanding America's Debt Problem

Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates (one of the world's largest hedge funds), gave two interviews to CNBC and Bloomberg recently in which he broke down how the U.S. debt situation could play out. His track record of predicting major economic shifts, including the 2008 financial crisis, makes his analysis worth considering.

The Core Problem

The U.S. debt has exploded from $5.7 trillion in 2000 to $34.8 trillion in early 2024.

The real issue isn't just the size - they are increasingly borrowing money to pay interest on existing debt. Interest payments hit $659 billion in 2023 and are projected to reach $1.4 trillion by 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

How Countries Get in Trouble

Dalio's research of economic history shows a clear pattern:

Countries start borrowing heavily during good times

When problems hit, they print money to pay debts

Their currency loses value

Eventually, investors stop buying their debt

This creates a "debt death spiral" where the country must borrow just to pay interest

The Treasury Market Crisis

The U.S. needs to sell a huge amount of treasury bonds (about 7.5% of GDP). But Dalio sees a serious supply-demand problem - there aren't enough buyers. Traditionally, when this happens, the Federal Reserve steps in by printing money to buy bonds. But this risks inflation and weakening the dollar.

Warning Signs He's Watching

Central banks showing losses (like the Bank of England's negative net worth in 2023)

Long-term interest rates rising despite Fed easing

The dollar weakens while bond yields increase

Rising debt service costs eating up more of the budget

The Japan Warning

Dalio points to Japan as a cautionary tale. Japanese government bonds became terrible investments due to ultra-low interest rates and a weakening currency. While Japan has managed to avoid a crisis, its economic growth has stagnated for decades.

Investment Implications

Dalio suggests:

Being cautious with traditional bonds

Holding 10-15% in gold as protection (he also mentions owning some Bitcoin)

Watching high stock valuations, especially in tech

Looking at companies that use AI effectively rather than just AI producers

Being aware that many investors are using borrowed money (leverage)

The 3% Solution

Dalio's proposed fix:

Cut the deficit from current 7.5% to 3% of GDP

Do it while the economy is still strong

Use three levers: spending cuts, improved tax collection (not necessarily higher rates), and careful interest rate management

Require coordination between Congress, the President, and the Federal Reserve

Historical Context

Dalio mentions this was achieved in 1992-1998, showing it's possible with political will. He emphasizes the current situation is like late 1998-1999: high asset prices, new technology excitement (then the internet, now AI), and brewing debt problems.

The Path Forward

Dalio isn't just predicting doom. He describes what he calls a "beautiful deleveraging" - where a country reduces its debt burden through a careful balance of:

Some deflationary measures (spending cuts, better tax collection)

Some inflationary measures (controlled money printing)

Structural reforms to boost productivity

Coordinated fiscal and monetary policy

For regular people, this means being careful with investments, understanding these risks exist, and planning accordingly. The biggest risk isn't a formal U.S. default, but rather a steady decline in purchasing power as the government likely turns to printing money to manage its debt burden.

Dalio's work seems particularly relevant now, as 2024 brings high debt levels, rising interest rates, geopolitical tensions, and technological disruption - all while the U.S. government continues to run large deficits.

🌱 Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side project we started, and it's starting to become fascinating in a weird and wonderful way. We write about whatever fascinates us on a given day that doesn't make it into the Daily Brief.

So far, we've written about a whole range of odd, weird, and fascinating topics, ranging from India's state capacity, bathroom singing, protein, Russian Gulags, and economic development to whether AI will kill us all. Please do check it out; you'll find some of the most oddly fascinating rabbit holes to go down.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

What is the latest takes or follow through articles . In case all articles are linked to latest status , it will help to navigate easily n compare thr reality vs predictions and forecasts.