Who Said What About FIIs, Small-Cap Bubble, Trump’s Tariffs, India’s Trade & Zepto’s IPO

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

This post might break in your email. You can read the full post in the web browser of your device by clicking here.

FIIs don’t believe in India story anymore?

Recently, Swanand Kelkar, a former MD at Morgan Stanley and now with Breakout Capital, came on ET Now. The conversation eventually veered into one of the most debated topics right now: Why are foreign institutional investors dumping Indian equities?

Whenever FII outflows make headlines, the usual chorus of assumptions kicks in. People say things like:

"They don’t believe in India's growth story anymore."

"Indian stocks are too expensive."

Kelkar disagrees with this narrative. According to him, these assumptions miss the bigger picture. The truth is, that global capital flows are driven by a range of external factors, including currency risks, U.S. rate hikes, and India's position within global financial benchmarks. Let’s break down the real reasons behind the outflows.

1. India Isn’t a Priority for Global Investors

Kelkar pointed out how global fund managers allocate their money:

Here’s what he means. Large institutional investors—think pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and mutual funds—allocate capital based on indices like the MSCI World Index.

This index heavily skews toward U.S. markets, with a 65-75% weight dominated by tech giants like Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon.

India, on the other hand, has a mere 2% weight in this index. If you look at the graph above–India isn't even mentioned. India's market isn't big enough to move the needle for global investors. When macro shifts like rising U.S. interest rates hit, fund managers often pull out of smaller allocations like India first—not due to weak fundamentals, but to manage risk and focus on larger markets. For many FIIs, it's more about their global strategy than anything specific to India.

2. Currency Depreciation Is a Major Concern

Kelkar emphasized another critical factor:

"You have to contend with rupee depreciation... Add up currency and tax, and you have a handicap of 400 to 500 basis points."

This is crucial for foreign investors. When they invest in Indian stocks, they do so by converting U.S. dollars to Indian rupees. But over time, the rupee tends to depreciate against the dollar—by 2-3% annually on average. This depreciation eats into returns when investors convert their profits back to dollars.

Here’s a simple breakdown:

An investor earns 12% in rupee-denominated returns from Indian stocks.

The rupee weakens by 3% over the same period.

The real return in dollar terms drops to around 8.6%.

Factor in India’s 12.5% long-term capital gains tax (LTCG), and the effective return drops even further.

Compare that to U.S. Treasury bonds, which currently offer 4.5-5% risk-free returns. For many investors, especially those looking for stability, India’s returns no longer justify the currency risk.

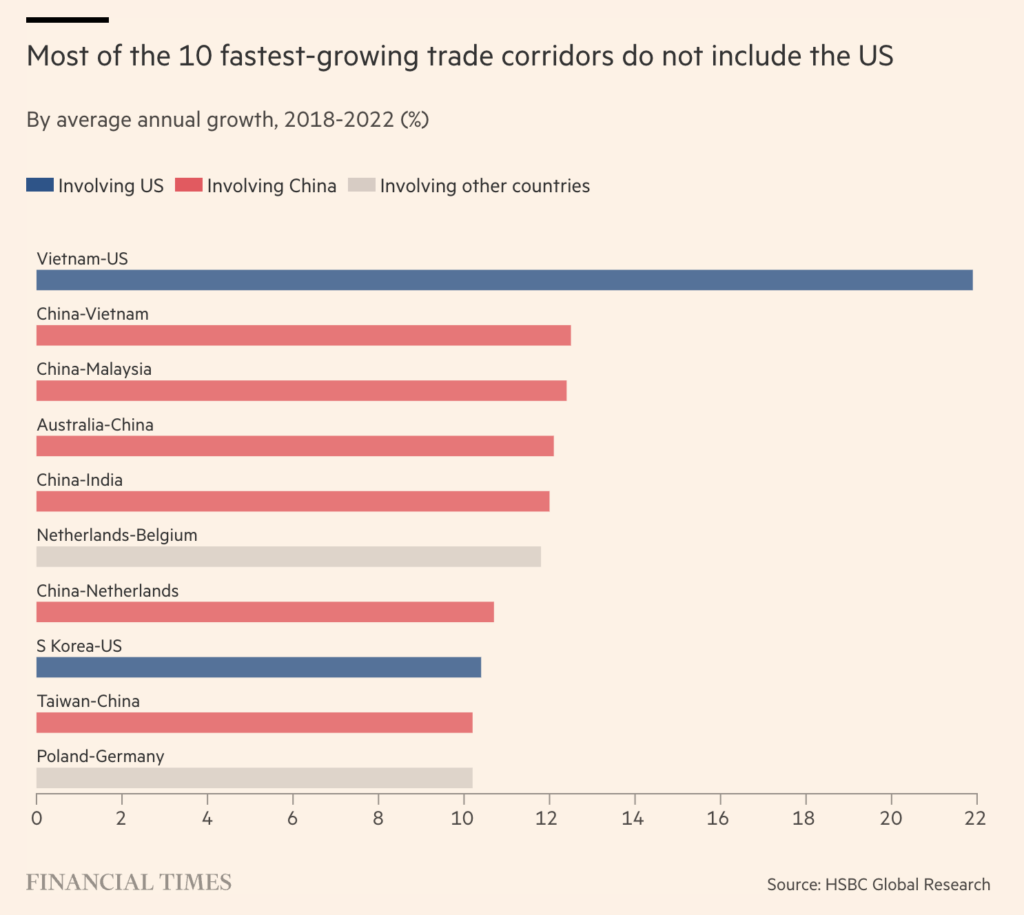

3. Emerging Markets Are Facing Similar Outflows

To add further context, We came across a post from Vinay Paharia, CIO at PGIM India Mutual Fund, which included a chart from Axis Capital Research.

This chart tracks rolling 12-month FII flows across emerging markets like Brazil, Korea, Taiwan, and India.

What does it show? Many emerging markets have seen significant FII outflows in recent months—not just India. This supports Kelkar’s point that FII behavior is often influenced by global portfolio strategies, not country-specific factors. When investors pull out of one EM market, they often do so across the entire asset class.

4. India’s Tax Policy Adds to the Disadvantage

Kelkar’s comments on taxes resonate with those of Samir Arora, the founder of Helios Capital. Arora has been vocal about how India's capital gains tax policy discourages foreign investors. He tweeted:

"No country, as in zero countries, charges capital gains taxes to foreign investors. This includes the U.S., UK, Japan, etc. India cannot be unique."

Here’s the problem:

In most developed markets, foreign investors are exempt from capital gains tax.

In India, FIIs must pay 12.5% LTCG tax on equities held for over a year and 20% on short-term gains.

For FIIs, this reduces net returns and makes India less attractive compared to markets with more favorable tax regimes. Arora has even suggested that scrapping the tax could help boost capital inflows and improve market sentiment.

5. Indian Markets Aren’t Delivering Enough Returns

Kelkar pointed out a simple but important fact:

"If you're only going to produce 10-12%, might as well consider U.S. Treasuries, which are yielding 4.5-5%."

Back when Indian markets were delivering 25-30% returns, FIIs weren’t as concerned about currency risk or taxes. But now that returns have moderated to 10-12%, those extra costs are harder to ignore. Investors seeking higher returns might look to other emerging markets or even risk-free U.S. assets instead.

Kelkar also touched on a few sectors: consumer discretionary (autos, real estate) could gain from fiscal spending and rate cuts; infrastructure and defense stocks have surged on capex but may correct if growth slows; and platform companies like Zomato are being rewarded for pivoting to profitability.

This is pretty much all that he mentioned. We really liked diving into this because some of our understanding around this is clearer now. Like we said in one of our previous episodes, we are new to the markets, and this show is a selfish way for us to learn more about them.

Good time to get out of small-cap?

So, S Naren the CIO of ICICI Prudential mutual fund said this in an interview with Livemint:

I believe this is the time to even stop small and mid-cap SIPs because they are so overvalued right now

It's a wake-up call from one of India's most respected fund managers, warning investors not to get trapped by the hype. Small and mid-cap stocks have become dangerously expensive, and Naren sees trouble ahead:

It is a sitter that in the medium term, small- and mid-cap SIPs are unlikely to deliver returns. If you invest at these levels, you are basically averaging out at very high valuations.

So why is Naren, known for his contrarian views, hitting the brakes? The problem lies in the market’s frothy momentum. He points out that small and mid-cap valuations have reached "absurd" levels.

A median price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) of 43 for these stocks has stretched far beyond sustainable limits. Worse, the profit-after-tax (PAT) contributions from these companies don’t justify their skyrocketing market caps.

“We looked at the entire PAT contribution versus the market cap... and again, it shows that the market cap contribution is much higher than the PAT contribution,”

Naren explained, underlining how the fundamentals don't back up the prices investors are paying.

This isn’t just theory. Naren has seen this pattern before. In 2017-2018, small and mid-caps rallied to similarly unsustainable levels. AMCs like ICICI Prudential, DSP, and SBI Mutual Fund took the drastic step of capping inflows into their small-cap funds.

Their reasoning was clear: when a market segment overheats, large inflows can force fund managers to invest at inflated prices, ultimately hurting both new and existing investors. After the rally broke, small-cap funds endured years of underperformance.

Naren believes the current situation is déjà vu. “Momentum has started to weaken,” he said, referring to technical indicators that track market trends. Both small and mid-caps have "broken completely and decisively" on these measures, signaling a potential downturn. He’s also worried about leverage. As investors borrow more to chase rising stocks, the market becomes even more fragile.

"When you have so much leverage, you have a situation where at any point in time you can have a problem," Naren warned.

Naren isn't against SIPs altogether; he just emphasizes that timing and valuations matter.

"Everyone says ‘SIPs sahi hain,’ but if you do it in the wrong product, you are headed for trouble," he explained.

His current focus is on large-cap and hybrid funds, which he believes offer better opportunities given India's stable macroeconomic outlook.

“This is maybe even the time to do aggressive SIPs in large-cap and flexicap funds,”

He noted, highlighting how foreign institutional selling has created attractive valuations in this segment.

The lesson here is simple: SIPs work best when you invest in undervalued markets. Naren has a reputation for cutting through market noise, and his advice now is crystal clear—small and mid-cap investors need to stay cautious or prepare for a long, bumpy ride ahead.

Tariff pe Tariff

We saw a tweet from Nitin Pai, co-founder of the Takshashila Institution and a leading voice on international relations. He said:

“The US is about to find out that other states are sovereign too; and they too can act in self-defeating ways.”

Now, if you’ve been following the news, you’ll know he’s referring to Trump’s tariffs. Pranav from the team has written about this topic twice in the past week. As for us? Well, before this, the only "tarif" we knew was the Hindi word for compliment. Thanks to Pranav and a bunch of others we’ve read to understand this better, we think we now have some sense of what's going on. Let us share everything we learned this week about tariffs.

So, what is a Tariff?

Think of a tariff as a cover charge at a club. The government charges this fee when goods enter the country, supposedly to protect local businesses. But if the cover gets too expensive, everyone suffers. The drinks (or foods) inside become unaffordably expensive.

Now, it’s not just a tax you pay once. In today’s globalized economy, products cross borders multiple times.

The Scale of Trump's Tariff Changes

In the first two weeks of his presidency, Trump placed a 25% tariff on imports from Mexico and Canada—then delayed it by 30 days the next day. Classic Trump. He also imposed an additional 10% tariff on all Chinese goods.

Here’s where things get serious. Before Trump, the average tariff on U.S. imports was just 2.4%. Now? It’s 10.5%. That’s one of the largest tariff hikes in U.S. history.

For context, economists Kyle Handley and Andrew Greenland pointed out that the last time tariffs spiked this dramatically was during the Great Depression with the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariffs. Those tariffs were so disastrous it took 50 years to undo their effects. And that was in a far less globalized world. Imagine the potential fallout today.

They also contributed to the great depression of the 1930s. Fun fact: Dow Jones index fell by 89% during the great depression

The Myth of Simple Solutions

Trump’s core argument is that tariffs will bring back American manufacturing jobs by forcing other countries to play fair. It’s a compelling narrative. Here’s one tweet we saw on this:

“The US is 4% of the world’s population but roughly 30% of global consumption. Tariffs work for us because we have the most desirable consumer market on earth and can force concessions in a way no other country can.”

This might seem like a winning strategy. In fact, it has worked in isolated cases. When Colombia refused to accept deportees from the U.S., Trump threatened massive tariffs. Within hours, Colombia backed down.

But here’s the thing: modern trade isn’t a simple transaction. You can’t just "bully" countries without serious repercussions.

Take cars, for example. César Hidalgo, a trade expert, explains how a single car part might cross the U.S.-Mexico border multiple times during production. Each crossing adds another tariff. A $100 engine part can rack up $56 in tariffs by the time it’s done. So much for the headline "10% tariff."

The same goes for other industries. U.S. oil refineries are built to process thick, heavy Canadian crude oil.

They can’t just switch to lighter American crude. Or take construction: most industrial-grade glass used in the U.S. is imported from Mexico. These tariffs don’t just raise prices—they disrupt entire ecosystems.

Why Simple Solutions Fail in Complex Systems

Kyla Scanlon, who’s probably one of the better content creators on economics and finance, points out another reason tariffs often fail:

Her point? You can’t just slap a tariff on complex supply chains and expect everything to magically fix itself. Global trade is like a machine with countless moving parts—messing with one part can break others.

The World Fights Back

Of course, other countries aren’t taking this lying down. China retaliated with 15% tariffs on U.S. energy imports and 10% on American agricultural equipment. They’ve also restricted exports of critical minerals used in defense industries plus an investigation into Google.

But the biggest retaliation is coming from America's closest allies. Canada imposed a 25% tariff on CAD 30 billion worth of U.S. goods. British Columbia even banned alcohol imports from "red states" that voted for Trump. That’s some next-level pettiness.

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers warns of the long-term impact:

“Jobs in the industrial heartland will be lost as American producers can't compete due to higher input costs. Canada and Mexico will lose trust in us. Immigration and drug risks will increase.”

Do Americans Even Want Manufacturing Jobs Back?

There’s also a broader question here: does America really want those lost manufacturing jobs?

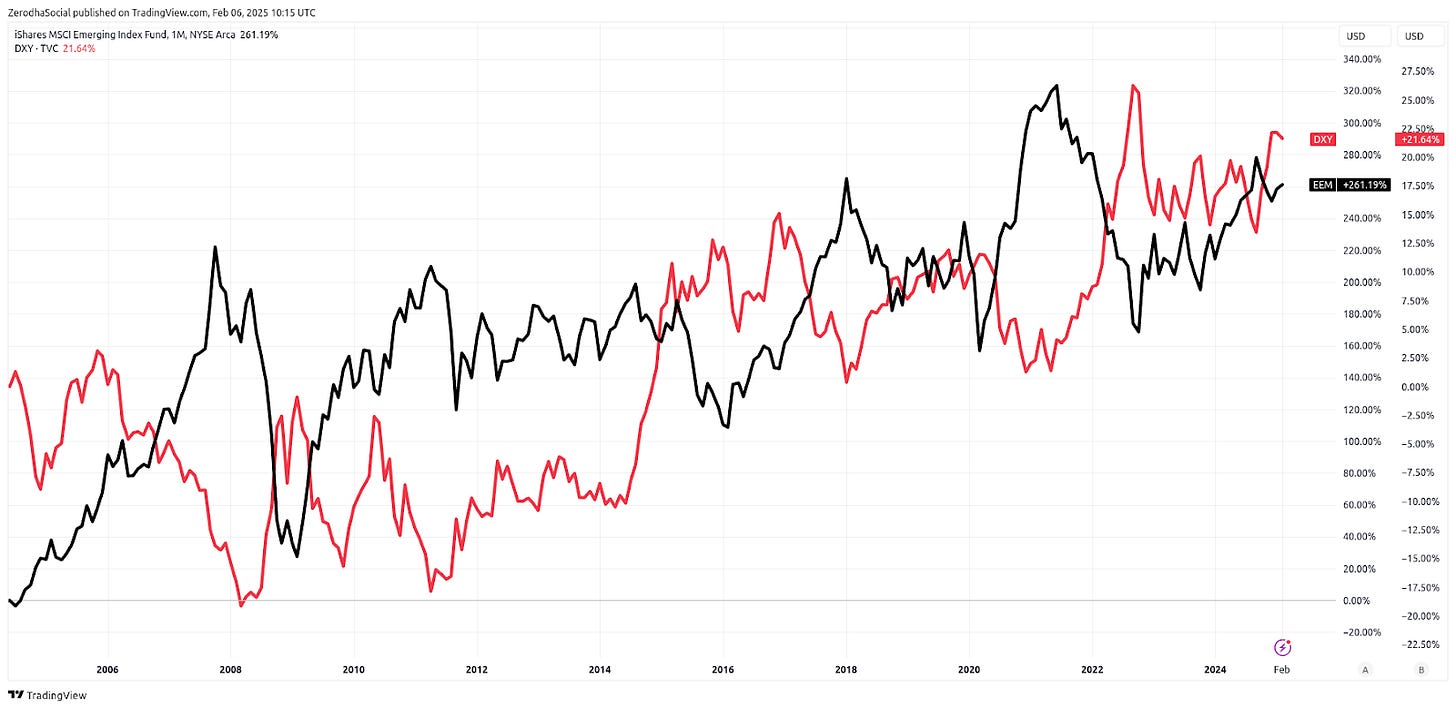

Economist Joseph Steinberg argues that trade with China didn’t just destroy jobs—it created better ones:

“The US didn’t 'subsidize' China by running a trade deficit. By selling the US cheap goods, China actually subsidized the development of the US tech sector.”

In other words, the U.S. may have traded low-paying textile jobs for higher-paying tech jobs. But Trump's tariffs could reverse that progress.

The Real Danger: Uncertainty

The scariest part of all this isn’t the immediate cost—it’s the uncertainty. Companies can handle high tariffs if the rules are clear. But constantly changing policies? That’s a nightmare. Imagine trying to start a business when you have no idea what your costs will be six months from now.

Research shows that this kind of policy uncertainty freezes investments. Businesses stop expanding because they can’t plan ahead. This is precisely what the post-World War II economic order was designed to prevent. Between 1950 and 2023, global trade grew by 4,400% largely because trade agreements reduced this unpredictability.

The New World Order

The most profound implication of Trump’s tariffs isn’t economic—it’s geopolitical.

Marco Rubio, Trump’s Secretary of State, recently acknowledged this shift:

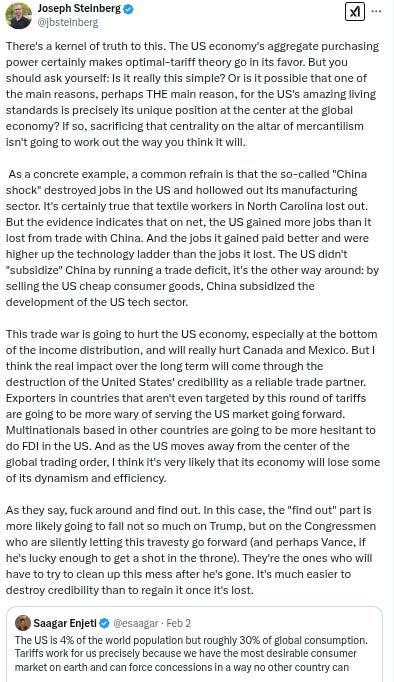

And we’re seeing this play out. Of the world’s ten fastest-growing trading corridors, only two now involve the U.S. China is stepping up as a rule-maker in global trade, filling the leadership vacuum America is leaving behind.

The Ultimate Price

This brings us back to Nitin Pai’s observation: sovereign states can act in self-defeating ways. America’s tariffs might give it short-term wins, but the long-term cost could be its role as the architect of the global economic system.

Kyla Scanon wrote this: “Trump is testing whether chaos itself can be monetized. But history suggests this is a dangerous game.”

The last time America embraced protectionism, it took 50 years to repair the damage. This time, the stakes are even higher. The question isn’t whether America can force its will on others through tariffs—it’s whether it’s sacrificing something far more valuable in the process maybe its reputation for instance.

By the way, Kashish one interaaasting guy from the team sent this on our group:

It's funny how the flag bearer of capitalism i.e. US has become so anal about protectionism and tariffs, while communist China can only fight its own domestic problems as they sell more and more goods abroad

India doesn’t have high tariffs?

Since we are on the topic of tariffs there is something else we came across that’s India specific. "We are signaling that India is not a tariff king," declared Finance Secretary Tuhin Kanta Pandey in a recent interview, emphasizing that India is open for business. The comment came alongside import duty cuts on certain goods in the latest budget. But while the government insists that India’s tariffs are globally competitive, many businesses might roll their eyes at that statement.

This tension between tariffs and policy predictability is a recurring theme in India's trade story. India has come a long way since pre-independence but there’s a long way to go, but let me give you context on how things were before long back.

The Shadow of Colonialism and the Rise of the License Raj

When India gained independence in 1947, the trauma of colonial rule was still fresh. For over a century, British policies had gutted India’s economy. By 1750, India accounted for roughly 25% of global textile production, but by 1947, it had become a supplier of raw materials to the British Empire.

This shaped Jawaharlal Nehru’s deep mistrust of international trade. Nehru believed that allowing unfettered foreign investment would reduce India to a neo-colony. His government responded with a policy of import substitution, aiming to build local industries by blocking foreign goods.

Enter the License Raj. Starting in the 1950s, the government imposed an elaborate web of regulations. Businesses needed licenses for nearly everything:

Expanding production.

Importing raw materials or machinery.

Even deciding how much to produce.

Tariffs on imports were astronomically high—some exceeding 355%—while entire categories of consumer goods were banned outright. Want a foreign car? Tough luck.

For decades, this system kept domestic industries alive, but barely. Companies had no competition and therefore no incentive to improve. Bureaucratic red tape strangled innovation. By the late 1980s, India was stuck in economic stagnation, with rising deficits and dwindling foreign exchange reserves.

The Crisis That Forced Change

By 1991, the situation was untenable. India had less than three weeks' worth of foreign currency reserves and faced a full-blown balance-of-payments crisis. Think of it like running out of foreign money. Just like you need US dollars to buy stuff from America, countries need foreign currencies (usually US dollars) to buy things from other countries. When a country runs out of these foreign currencies, it's like being broke - they can't buy important stuff from other countries or pay back their international loans. That's a balance of payments crisis.

Desperate for an IMF bailout, India was forced to dismantle the License Raj and liberalize its economy.

The reforms were sweeping:

Import licensing was abolished for most goods.

Tariffs were drastically reduced. By 2008, the peak tariff rate had fallen to 10%, from 355% in 1990.

Foreign investment was welcomed, leading companies like Pepsi, General Motors, and Microsoft to establish operations in India.

These reforms sparked an economic boom. India’s GDP grew rapidly, and industries like IT and automotive flourished. For a while, it seemed like India had left its protectionist instincts behind.

But then something changed.

Back to Protectionism: Make in India’s Dilemma

Since 2014, India has quietly increased tariffs again. Under the Make in India initiative, the government wants to strengthen domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on imports. While the overall average tariff rate has risen modestly—from 13% to 14.3%—the increase is more dramatic in key sectors.

Today, imported cars face tariffs of 125%, motorcycles 100%, toys 70%, and textiles 25%. Even worse, the share of tariff lines with rates above 15% has more than doubled since 2010. The government argues that these measures protect local industries and create jobs, but critics warn that they discourage foreign investment.

The recent budget’s duty cuts on vehicles may signal a softening stance, but businesses remain skeptical. After years of steadily rising tariffs, a few reductions are unlikely to erase concerns about policy unpredictability.

The recent Volkswagen’s Case

This brings us to the Volkswagen case from last week in The Daily Brief. Volkswagen’s tax dispute illustrates a deeper issue than tariffs alone: regulatory unpredictability. The company has been accused of dodging duties by importing car parts separately instead of bringing in complete knocked-down kits (CKDs), which are taxed at 30-35%. Volkswagen insists it followed the rules and that Indian authorities approved the strategy in 2011.

But over a decade later, the government has changed its stance, issuing a $1.4 billion tax demand. Volkswagen’s frustration is understandable. They even said this:

The company described the tax demand as a “body blow” to India’s much-touted “ease of doing business” initiative, warning that such surprises make global companies rethink their investments.

In plain terms, Volkswagen is saying: “This kind of surprise makes us—and other global companies—think twice about doing business in India.”

Imagine running a business where you follow the rules, only to have them rewritten retroactively.

This isn’t an isolated case. The Vodafone and Cairn Vedanta disputes followed a similar pattern. Vodafone won a Supreme Court case against a multi-billion-dollar tax demand, only for the government to change the tax laws retroactively to make Vodafone liable. Cairn’s assets were even seized before the dispute was finally settled.

India’s journey from colonial exploitation to protectionist policies and then economic liberalization has been long and complex. Today, the challenge is twofold:

Creating a competitive tariff environment that encourages trade.

Building trust through policy predictability and stability.

Zepto wants to challenge Swiggy and Zomato on the bourse

It’s been a while since we spoke about our favorite topic—Quick commerce. You see, Zepto’s been on a mission lately to bring in more domestic money. Their previous funding round with Motilal Oswal Private Equity was already a step in this direction. Now, they’ve reportedly tapped domestic mutual funds for a $300 million secondary share sale, aiming to dilute the foreign investors’ stakes and get the ownership structure more in line with Indian laws.

We came across Deepak Shenoy’s tweet on this:

“Zepto needs to bring foreign ownership below 50% so they classify as an Indian company for not getting dinged on controlling inventory.”

Here’s the context. See in India, if a company is foreign-controlled in India, which Zepto currently is, it can’t legally own inventory under current FDI rules for e-commerce. So if Zepto doesn’t fix this, it risks falling afoul of the law—a nightmare scenario when your entire quick commerce model depends on tight control over inventory and logistics.

This isn’t just theory either. Piyush Goyal has previously hammered home the point that e-commerce firms must follow local laws to the letter, particularly when it comes to ownership structures and inventory control. Platforms like Amazon and Flipkart have spent years navigating these waters, setting up complex structures with third-party sellers and local partnerships to stay compliant. Zepto, however, is trying a different route—becoming more "Indian" by ownership to avoid those legal battles altogether.

Deepak Shenoy also made another important observation: “

“Mutual funds can’t really buy pre-IPO, unless the IPO is immediately happening. Might have to be at IPO.”

This hints at a timing challenge for Zepto. They’re courting domestic mutual funds for a share sale just ahead of their DRHP filing, but mutual funds typically prefer clearer IPO timelines to justify such investments. We have no clue either on whether mutual funds have done this ever before.

But it will be interesting how this evolves.

🌱 Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side project we started, and it's starting to become fascinating in a weird and wonderful way. We write about whatever fascinates us on a given day that doesn't make it into the Daily Brief.

So far, we've written about a whole range of odd, weird, and fascinating topics, ranging from India's state capacity, bathroom singing, protein, Russian Gulags, and economic development to whether AI will kill us all. Please do check it out; you'll find some of the most oddly fascinating rabbit holes to go down.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

Excellent Article . Uncovering the noise around and writing straight to the point .

Kudos 👏

Fantastic insights! 👏👌