Who Said What About FII Taxes, Small-Cap Boom, Market Panic, Trump Tariffs & Dalio’s Warning

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them. You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

Today, we have six very interesting comments from last week.

The Capital Gains Tax Debate: Foreign Investment in India

Samir Arora, the CEO of Helios, recently said something about FII investments at an event that everyone and by that, we mean the finance Twitter crowd has been talking about.

So, here’s the situation: India imposes a 15-20% capital gains tax on Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs). He called this policy “100% wrong,” arguing it’s a critical mistake that could be hampering India’s investment growth. We’ve touched on this before, but this time around, Samir brought in even more nuance and detail.

What exactly is Samir Arora saying?

Let’s break it down step by step:

Outlier status

Arora claims India stands out globally for taxing foreign investors on capital gains. He uses the phrase “199 out of 200 countries” to emphasize that almost no one else does this. Now, is it literally 199? Tough to verify, but you get the point: India’s policy is unusual compared to international norms.Who gets hit?

The investors facing this tax include major sovereign wealth funds (like GIC of Singapore), pension funds (think Canada Pension Plan or Norway’s Government Pension Fund), university endowments (Harvard, Princeton), and high-net-worth individuals living in low-tax placesWhy is this a problem?

According to Arora, these funds are typically tax-exempt at home—so they pay zero capital gains tax when they invest in markets like the U.S. But in India, they get slapped with a 12.5% LTCG. Even worse, they can’t offset it against any taxes back home because, well, there aren’t any. Arora’s blunt line is: “There is no tax there, what to do?”Real return after depreciation and tax

Next, we’ve got the math issue: if these investors earn 10% in rupees, and the rupee loses about 5% against the dollar, the dollar return is already down to around 5%. Then you apply capital gains tax. That brings the net gain down to maybe 3-4%. In a world with many more attractive investment destinations, that’s a tough sell.

The big picture

He also looks at the big picture on what India actually collects:

In the 2022-2023 fiscal year, India brought in roughly 99,000 crores (about $11 billion) from all capital gains taxes. In weaker years, however, a lot of that is offset by carried-forward losses.

Over a five-to-seven-year cycle, he estimates that maybe $3-4 billion per year actually sticks as revenue from foreign investors.

So, Arora’s question is: Is it worth pulling in a few billion in taxes if it potentially scares away much larger pools of global capital?

Why FIIs matter to the larger ecosystem

Here’s where Arora makes a deeper point about how different parts of the investment world fit together:

FIIs might seem like short-term traders chasing quick profit. But…

Private Equity (PE), which does create jobs and bring in technology, needs a healthy market with plenty of buyers to exit its investments.

Those buyers often include FIIs, who bring the dollars needed when PE firms cash out. If FIIs are discouraged, PE investments become riskier—and that could reduce the flow of money that actually helps build companies, create jobs, and foster tech growth in India.

In Arora’s words: “We like private equity because they create jobs, they bring technology, but if they don’t have an exit … they can’t sell it all to domestic mutual funds.” In other words, it’s one giant, interconnected web.

Deepak Shenoy is on board with removing the tax but frames it slightly differently. He says India has reached a point where a quirky, non-standard tax might have been fine when the country was smaller, but “at scale, it’s a pain.”

Translation? As India grows into a major global economy, the old rules might be holding it back. What once worked in an emerging market might be out of place for a soon-to-be economic powerhouse.

Counterarguments

Not everyone agrees with Samir Arora. Some people point out that investors seemed fine paying these taxes before. So, if India remains a hot market, what’s stopping them from coming in anyway?

This raises the question: Does India need to conform to global norms to attract capital, or does its growth story stand on its own? And is it fair to change the rules for those who’ve already been investing, possibly on less favorable terms?

A look at the historical background

Arora has been sounding the alarm since 2018, saying this was bound to affect foreign flows over time. He also notes that:

Capital gains tax for FIIs was zero before 2018.

When the government introduced the Securities Transaction Tax (STT) years ago, it was meant to replace capital gains taxes. But now, foreign investors face both—essentially double taxation, from their viewpoint.

So, what’s the bottom line?

Here’s why this debate really matters:

India’s Global Standing

As India rises to become the world’s third-largest economy, do these tax policies, set in a different era, still make sense?Balancing Act

India’s government has to weigh the tax revenue it earns against potentially massive investment flows—flows that can fuel startups, infrastructure, and long-term economic growth.Ecosystem Effects

Everything is connected. Changes to how FIIs are taxed ripple through private equity, job creation, and even technology transfer.

At the end of the day, should India align with global standards (that generally don’t tax foreign capital gains) or keep its own approach because it’s worked so far? There are strong opinions on both sides, and it’s not a trivial choice.

That’s the full story behind Samir Arora’s fiery remarks. Do you believe India should drop the capital gains tax to attract more global money?

The small cap sage

Samit Vartak of SageOne Investments recently gave an interview to NDTV Profit, and he touched upon a bunch of interesting things.

The opportunity in fear

Samit believes fear can be your friend if you know where to look. As he puts it, “It’s always good to have too many worries around you. That’s where you find value.”

He points out that every 3–4 years, markets typically go through a “sale”—a correction that often starts when sentiment gets really negative. According to Samit, the correction that began around September 2024 is following this 3–4-year pattern, and corrections usually last about 6–9 months.

In fact, when they’re sharper, they often don’t drag on as long.

“You will never get such a big sale unless there are warning signs around you,” Samit says. He’s actually happy when everyone else is worried because that “means weak hands can’t withstand such warnings. Only strong hands will.”

In other words, the more negative the headlines, the bigger the potential discount for investors ready to pounce.

The valuation misconception: Large Caps vs. Small Caps

A lot of people assume large-cap stocks are cheaper than mid- or small-caps. But, Samit challenges that idea with a closer look at valuation metrics. He had tweeted about this earlier, and we had covered this in one of the previous episodes.

He explains that large caps might look cheap—trading at, say, 9 times forward earnings or 21–22 times trailing earnings—but this is skewed by the mix of sectors in the large-cap space. Around one-third of large-cap profits come from PSU (Public Sector Undertaking) companies, which often trade at 8–10x multiples, and about 17% of large-cap profits come from private banks, which sit around 15–17x.

If you remove those PSUs and banks from both the large-cap and small-cap buckets, you get a very different comparison:

Remaining large caps: often trading at 40+ multiples

Similar small caps: about 30–32x

“That’s the real comparison because you can’t just look at the average and say large caps are cheaper,” Samit emphasizes. Sector composition matters.

The liquidity factor

Ever wonder why good stocks also fall during a market sell-off? Samit argues it’s often liquidity, not fundamentals, that drives these short-term moves—especially in the small- and mid-cap space.

“When liquidity comes down, good or bad doesn’t matter; everything falls.”

Smaller companies feel the pinch more because it only takes a few sellers with no buyers on the other side to drive the price down sharply. Ironically, this is where the opportunity lies—when there’s a “liquidity vacuum,” you can pick up quality stocks at cheaper prices.

The multi-bagger formula

What sets Samit apart is his systematic approach to finding multi-baggers—stocks that can grow 10x or more. He studied companies that delivered 10x returns from the 2008 market peak to see what made them tick. Here’s what he found:

Higher sales growth: 15% versus 10% for non-multi-baggers

Higher starting ROE: 25% vs. 22%, and a more sustainable ROE over time

Lower starting valuations: They were 15–20% cheaper

Smaller starting market caps: Around ₹3,400 crores vs. ₹10,000 crores on average

He concludes that small caps have double the probability of becoming multi-baggers compared to large caps, and a big reason is simple math.

“The smallest large cap today is around ₹1 lakh crore. For it to go 10x in 10 years, that’d be ₹10 lakh crore—easily a top five company in India. That’s just not realistic unless it’s a total outlier.”

The private capex reality

There’s a common narrative that private capex (capital expenditure) in India is weak—large industrial players in steel or cement aren’t expanding aggressively right now. But Samit sees another story playing out in quality small caps.

“Most of the good-quality small-cap companies I know are in the middle of a massive capex cycle. Many are doubling their capacity over the next 3–4 years.”

These expansions are small from a macro perspective, so they don’t move the needle in national statistics. But for investors, those capacity increases can be huge drivers of future growth.

Managing portfolio drawdowns

If you’re an investor watching your portfolio drop 20%, 30%, or even 50%, Samit has practical advice:

Mentally Reset: Pretend you’re starting fresh with new money, rather than fixating on losses.

Tax-Loss Harvesting: If you’re sitting on losses, this can be a smart time to sell, reduce your tax bill, and reinvest in more attractive opportunities.

He reminds us that quality companies can bounce back quickly when the market turns. For example, small caps fell 70% in the 2008–2009 crash but recovered 3.5x in just 14 months—basically regaining all their lost ground.

But a word of caution: 70–80% of stocks that soared in a bull run might never see those highs again for years.

The long-term imperative

Finally, Samit underscores the importance of patience, especially in small-cap investing.

“There have been periods in history—four, five, even eight years—where the market delivered no returns. If you’re investing in small caps, you need to look beyond just the next 12 months.”

This long-term lens helps him stay focused on companies with sustainable ROEs and market share gains. Sectors rise and fall, but a company growing its market share can thrive even when the broader space is struggling.

The bottom line

Samit’s big takeaway? Don’t just chase “hot” sectors—look for companies that consistently grab market share because that often drives resilient ROE and growth over the long haul.

“If you’re only betting on a sector story, you’re at the mercy of the cycle. But if you’re investing in a company that gains share year after year, it’s much more likely to deliver strong returns—even in tough times.”

Market Corrections: The How, When, and Why of Market Recovery

Now, for this segment, we’ve gathered comments from four of the most respected market voices—Samir Arora, Samit Vartak, Raamdeo Agrawal, and our boss, Nithin Kamath.

The Time Factor: Historical Correction Patterns

Let’s start with Samir Arora, who looks at past market cycles and sees a pattern:

“If you look at 2000, 2008, they last 8-10 months in which they fall a lot, and then they hang around for 3-4 months, and then a new round happens. So if you look at it like that, there’s another one or two months [to go].”

He points out that our current correction began in September 2024, which means we’re about 6-7 months in. If history is any guide, we’re possibly nearing the tail end of the most severe phase.

Samit Vartak adds a similar timeframe but explains further:

“Last correction we had started in December ‘21 and continued towards ‘22, probably half of the year, and then 3 years down the line again, September ‘24 is when we had the peak in the market. I’ve seen that the average duration of correction is 6 to 9 months, and the faster it corrects, the shorter is the duration.”

Meanwhile, Raamdeo Agrawal frames this as a healthy, even expected, correction:

“After four years of relentless rally, if we are there for 6 months out here… last year we made 50% in the market, broad market I’m saying, and we have lost 20-25%. It is painful, I understand, but it is very logical. It’s a proper healthy correction.”

First-Time Investors: A Different Experience

For newer investors like us—especially those who started investing after the pandemic—Nithin highlights that this is their first real correction:

“Markets are cyclical, and given the way our markets went up from late 2020, this fall was inevitable.”

He recently tweeted that this is exactly why Systematic Investment Plans (SIPs) matter:

“What an SIP helps you do is to average your investments across different market cycles. You averaged on your way up from 2021; now, you get to average on the way down.”

And if you’re looking for more on that, Bhuvan from the team wrote a long blog post on how to deal with bear markets.

“Historical data suggests that SIPs which delivered comparatively lower returns in the initial 5 years have delivered better returns on a 10-year basis. During the 2020 COVID crash, large, mid, and small caps fell by 25-40% but then rose by 200-400%. If you had panicked, you would have missed the rebound.

Depth vs. Duration: How Much Further Could Markets Fall?

When it comes to how deep this correction might go, we see some differing views.

Raamdeo Agrawal feels large caps might already be close to fair value:

“The P multiple which was 23-24, that has come down to less than 20, and it is below the 10-years average. Nothing stops at the average, it overshoots a little bit. So if market corrects further from here, it is overshooting on the downside.”

However, he does think mid and small caps might need more time:

“If you see today, on a five-year basis, midcap is up 177-180%. So the gap is too much. That excess gain either large cap has to catch up to match midcap, or midcap has to keep correcting time-wise or actual downfall.”

Samir Arora isn’t 100% sure if we’ve hit bottom yet, but he believes that economic triggers, not just the clock, will mark the turning point:

“By April-May, time would have been 8 months, and second is by that time this situation of Trump and negotiations would also end. If you are very market-oriented, you’ll say these falls take 8 months. If you are very macro-oriented, you’ll say we are waiting for Trump uncertainty to end.”

The Catalysts: What Will Trigger Market Recovery?

Each expert has a different take on what could spark the market back into rally mode.

Samit Vartak believes that no matter when the broader market recovers, returns will largely come from quality companies:

“I don’t know what will happen in the next three months or four months, but I’m pretty sure if you are a good stock picker, from a three-year perspective, there are exciting opportunities, and it will be shocking to me if you can’t make money over a 3-4 year period.”

Raamdeo Agrawal points to earnings growth and the supply-demand balance returning in equity markets:

“Your IPO markets are now shut almost, like frozen. Credit flow is improving, government expenditure is picking up. I think all the things are falling in place, and correction has also happened.”

So, what’s the takeaway? Here are the recurring themes:

We’re likely in the later stages of this correction (6-9 months in).

External factors—like Trump’s tariffs—could influence the exact timing of a turnaround.

Mid and small caps may still need extra time to correct.

Quality companies with strong fundamentals will likely recover the fastest.

The Macro Chess Player: Manish Dangi's Market Insights

While everyone is talking about market corrections, Manish Dangi, founder of Macro Mosaic Investing and Research, in an interview with NDTV profit, spoke about the global macro picture.

Tariffs: More Than Just Bargaining Chips

Dangi sees Trump’s tariff policies not just as short-term negotiation tactics but as strategic moves in a global “chess game.” According to him:

“The man is more ideological today than he was in the first term. He is more determined, has less worry of its impact.”

In other words, Trump is less concerned now about how tariffs might rattle equity markets compared to his first presidency.

Dangi then delivers a surprising perspective on tariffs and inflation:

“At margin in US, for the first order, it’s going to be inflationary, but eventually the growth actually takes a bigger hit... when big tariffs are imposed, eventually, paradoxically, rates actually come down, they don’t go up.”

Why would interest rates go down if tariffs typically raise costs? Dangi says currency adjustments will absorb much of the inflationary shock:

“If the dollar adjusts and appreciates... the TV and the fridge that they bought from China pretty much may cost the same.”

So, while tariffs can initially spark price increases, the stronger dollar could end up stabilizing US consumer costs, even if overall growth slows down.

The "Malignant" Impact on Emerging Markets

But what about the rest of the world? Dangi warns that emerging markets like India, could face a serious fallout:

“What tariffs do to the outside world is out-and-out malignant. The impact of this to the outside world is substantially more because for us the only risk currency is dollar. There is absolutely no way that dollar strengthens and India has a reflation.”

In simpler terms, a rising dollar makes life tough for emerging markets because it tightens financial conditions and can choke off growth. He also points to USD's strength as a key signpost:

“If you have nothing else to sort of track in terms of risk-on/risk-off, just the USD movement itself is almost a very cool indicator.”

Foreign Investment Flows: Don’t Count on Them

Many folks on the street are banking on foreign investors (FIIs) to bounce back into Indian markets after the recent selloff, but Dangi isn’t convinced:

“I’ve been an FII pessimist for many years... given demographics in US, this case of FII money on a secular basis coming in ended in 2010s, early 2012-13-14. After that, on net basis, FIIs come and go.”

He suggests India has evolved to a point—similar to South Korea in the 1990s—where domestic capital is robust enough to drive the market without relying on foreign money. This is good news in terms of self-sufficiency, but it also means we shouldn’t expect those big waves of foreign investment we once saw.

The China Factor: A New Competitor for Capital

Another curveball Dangi throws into the mix is China’s potential resurgence as an emerging market favorite:

“There is seriously a case of US-China sort of cozying up... and can potentially threaten Indian hegemony in emerging markets that we are the only play in the ground.”

He speculates that improving relations between the US and China could unlock “hundreds and hundreds of billions of dollars” in Chinese markets. With China appearing cheap, showing signs of recovery, and poised for possible fiscal stimulus, international investors might just decide to park their money there instead of India—especially if Beijing is no longer treated as a global outcast.

Valuations: They Don’t Have the Muscle

You often hear analysts say, “Valuations are so attractive now; that alone should bring investors back in!” Dangi pushes back on that idea:

“Valuations don’t have muscles to lift markets... it’s perhaps a lubricant, it can almost assure you of good returns if you actually buy cheap, but it doesn’t have the muscle.”

Simply put, prices might look attractive, but without a real catalyst—like strong earnings, policy shifts, or global tailwinds—cheap stocks can stay cheap for a long time. As Dangi bluntly states:

“Never buy cheap just because it’s cheap.”

Another key concern for Dangi is corporate profit margins. He points out that equity valuations don’t add up if margins start sliding:

“At 9-10% of nominal GDP growth, at 20 times earnings, the equity math does not add up. On top of it, you have to accept the fact that the margins haven’t rolled over yet.”

He compares the current situation to 2009-14, when India’s historically high returns on equity took a nosedive:

“We were all wondering as to why this country that was delivering 20-25% ROE in 2000s was barely scratching the surface at 12-13-14%.”

It’s a warning that past performance doesn’t necessarily repeat if the fundamental drivers—like global conditions, corporate profits, and currency dynamics—aren’t in place.

Ray Dalio on America's "Fiscal Heart Attack" and Gold

Ray Dalio, the legendary investor, made some comments about America facing a potential "fiscal heart attack" and his suggestions about gold as a safe haven.

He recently appeared on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast with Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal. He was there to discuss insights from his new book, How Countries Go Broke: Principles for Navigating the Big Debt Cycle—a deep dive into how debt builds up and what happens when it gets too big to manage.

The soundbite causing a stir is Dalio saying something like:

“If you don’t do it and there’s the crisis that I’m saying will come, and I can’t tell you exactly when it’ll come... my guess would be three years, give or take a year, something like that.”

He compared this looming crisis to a heart attack. You never know exactly when it’ll happen—only that the underlying conditions mean it’s likely.

And then there was another quote about gold:

“Oh, yes, I think the gold—and I’m not trying to harp on gold, and I don’t want people to run out and go buy—they will though, they will...”

Now, you might think he’s calling for an imminent financial apocalypse and telling everyone to buy gold tomorrow morning. But let’s see what he was really saying.

The Context

Ray Dalio isn’t just some random YouTuber talking about finance. He founded Bridgewater Associates, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, and he’s studied how economies behave over centuries. So when he talks about a “fiscal heart attack,” he’s not throwing around buzzwords—he’s drawing from decades of research on what he calls the “big debt cycle.”

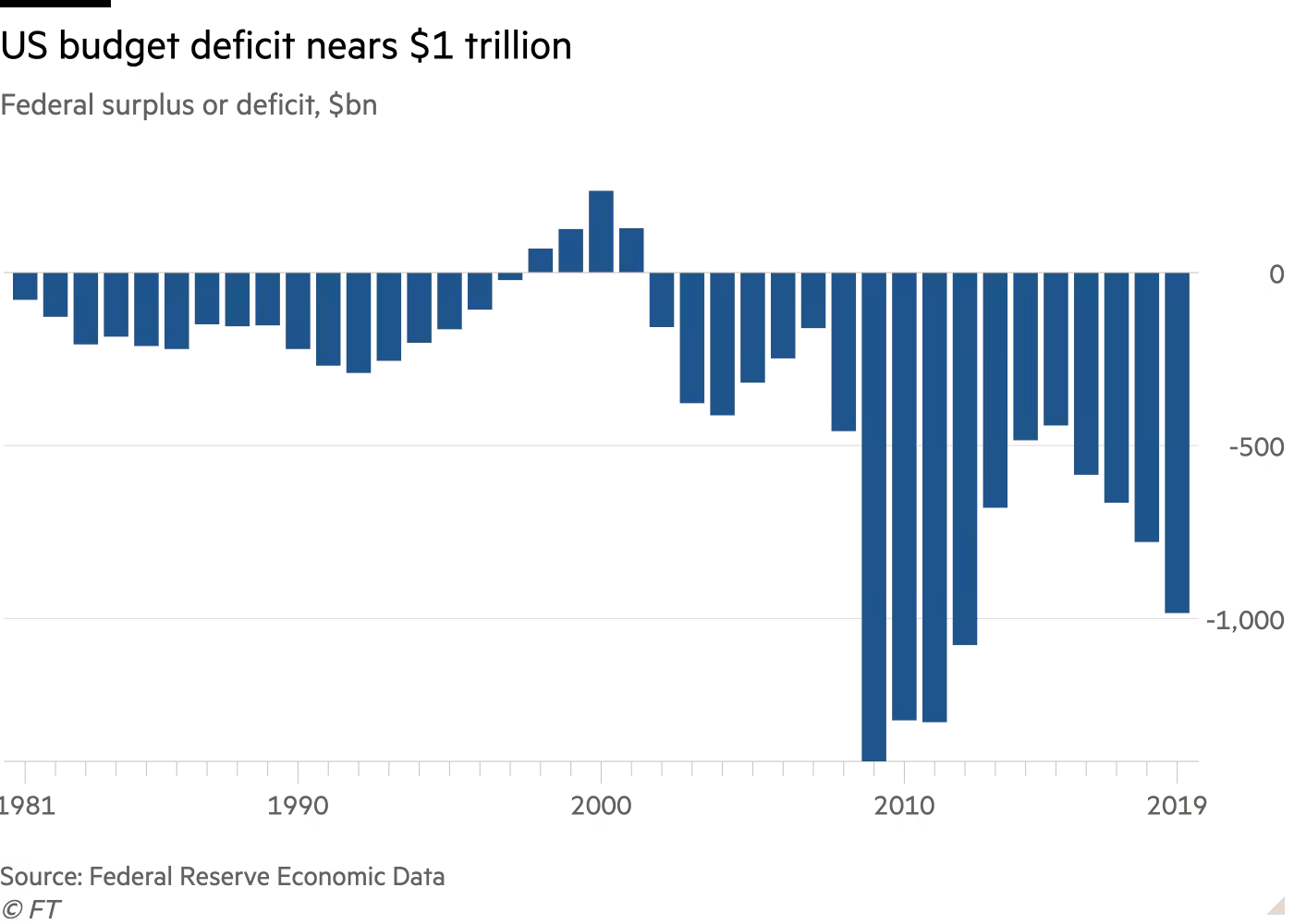

The U.S. currently has a significant debt problem:

The budget deficit in 2024 was around $1.8 trillion, which is roughly 7.5% of the GDP.

Interest on the government’s debt is about $1 trillion per year.

Plus, we’re constantly rolling over old debt while issuing new debt to cover the growing deficit.

Dalio’s argument is that we’ve reached a point where we have so much debt relative to income—both at a government and individual level—that we’re at risk of a crisis if investor demand for U.S. government bonds dries up.

In his view, one person’s debt is another person’s asset. But once there’s too much debt, confidence can wobble. If demand for bonds weakens, the Federal Reserve usually responds by printing money to buy these bonds—devaluing the currency in the process.

That’s the “heart attack” analogy: too much “plaque” in the system eventually leads to something big and ugly.

The Solution

Now, Dalio isn’t just out here screaming doom. He has a proposed fix he calls the “3% pledge,” meaning the US should aim to bring the budget deficit down to 3% of GDP—about half of where it is now. He cites the period from 1992 to 1998 as a real-world example of when this was achieved.

He also says fiscal tightening needs to happen alongside some monetary support, striking a balance between trimming government spending (or raising revenue) and not letting the economy collapse from lack of stimulus.

The Gold Comment

About gold: Dalio wasn’t giving a blanket “buy now!” command. In fact, he explicitly said he wasn’t trying to harp on gold. But he acknowledged that in the kind of crisis he’s describing—where currency is devalued—gold historically performs well. He suggested a 10-15% allocation might be wise for diversification.

He even mentioned that Bitcoin could serve a similar purpose, alongside gold, as a sort of insurance policy when people lose confidence in fiat currencies.

The Bigger Picture

What’s really worth noting is Dalio’s method: historical analysis. He said his perspective on markets changed in 1971, when President Nixon took the U.S. off the gold standard. Rather than panic, he studied how similar moments played out before—like what Roosevelt did in 1933. That approach helped him anticipate events like the 2008 financial crisis.

In his latest research, Dalio uses a “risk gauge” to illustrate where the U.S. stands. He says the long-term risk gauge is at 100%, meaning vulnerabilities have piled up over decades. But the short-term risk gauge is at 0%, meaning there’s no immediate, obvious trigger for a collapse.

That’s why he uses the heart attack analogy—you know the arteries are clogged; you just don’t know the exact day the heart attack might happen.

This is the nuance that often gets lost in sensational headlines. Yes, Dalio says a big crisis could happen in the next few years. But the main takeaway isn’t “Run for the hills!”—it’s understanding how debt cycles work and how to manage them.

Whether you fully buy into his timeline or not, Dalio’s broader point about fiscal sustainability is worth a closer look.

🌱 Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side project we started, and it's starting to become fascinating in a weird and wonderful way. We write about whatever fascinates us on a given day that doesn't make it into the Daily Brief.

So far, we've written about a whole range of odd, weird, and fascinating topics, ranging from India's state capacity, bathroom singing, protein, Russian Gulags, and economic development to whether AI will kill us all. Please do check it out; you'll find some of the most oddly fascinating rabbit holes to go down.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

‘ Invert always Invert’ - Charlie Munger

For and against on the topic is the best strategy and keeps us away from the biases. Thank you for doing this!