When economics needs a (battery) chemistry lesson

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The electrifying business of battery chemistry

How US tariffs are putting pressure on Indian textiles

The electrifying business of battery chemistry

Take a moment to look around. The phone in your hand, the laptop on your desk, the wireless headphones you use on the metro, the solar panels on rooftops storing energy for the night — they all run on batteries. They power our daily lives in small, invisible ways and in big, industrial ways. They’re the hidden plumbing of the modern economy.

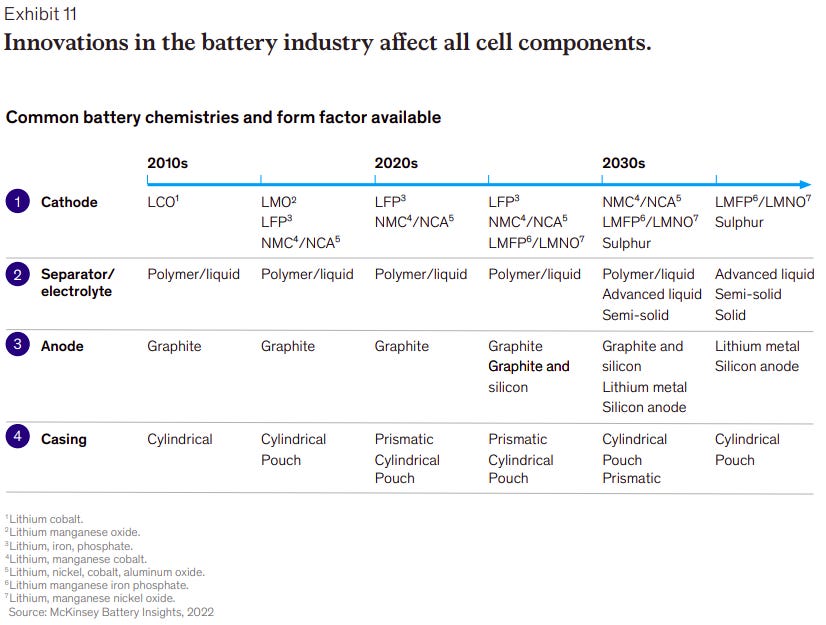

And the interesting part is while all batteries have the same parts, the chemistry used to arrange them will influence many things differently: like how quickly it recharges, how safe it is, how much it costs, and who in the supply chain makes money.

That’s why battery chemistry matters to economics. For example, if the world leans toward a cobalt-heavy chemistry, the Democratic Republic of Congo (where 70% of the world’s cobalt is mined) suddenly becomes the center of the universe. If the world pivots toward cobalt-free chemistries like LFP, that entire power balance shifts — and so does the investment opportunity.

The way we like to think of it: chemistry is the business model of the battery industry. Swap the chemistry, and you change the cost structure, the winners, and the losers.

But what do we mean by chemistry? Is there any one all-winning chemistry? What decides which chemistry wins? We wanted to try and find an answer to these questions with first principles — in fact, we touched upon some of them in our earlier piece on batteries.

This is the sequel of that story. Let’s dive in.

Clearing the Basics on battery

We toss around the words “battery” and “cell” like they mean the same thing. But the thing is, they don’t.

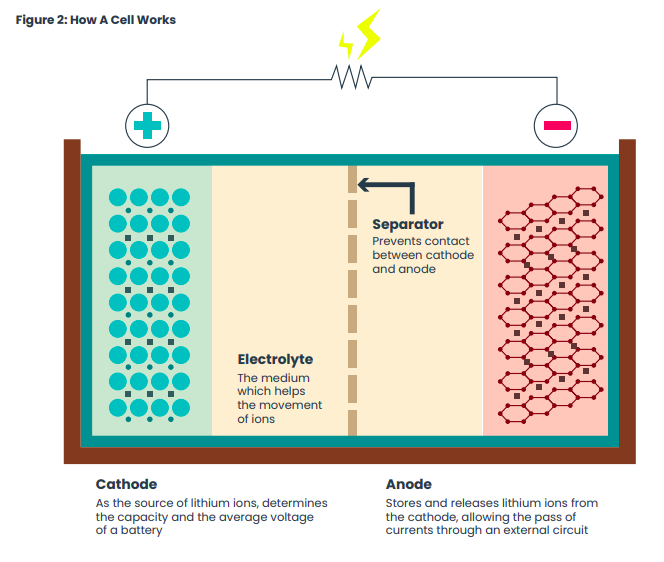

A cell is the fundamental building block of a battery, and has four parts. There’s the cathode (positive side) and the anode (negative side), between which the electrons move. This flow of electrons is what causes your torch to light up or fan to turn on – that’s how electricity works. The electrolyte provides the fluid medium which allows the electrons to swim, while a thin separator keeps the two sides from touching and short-circuiting.

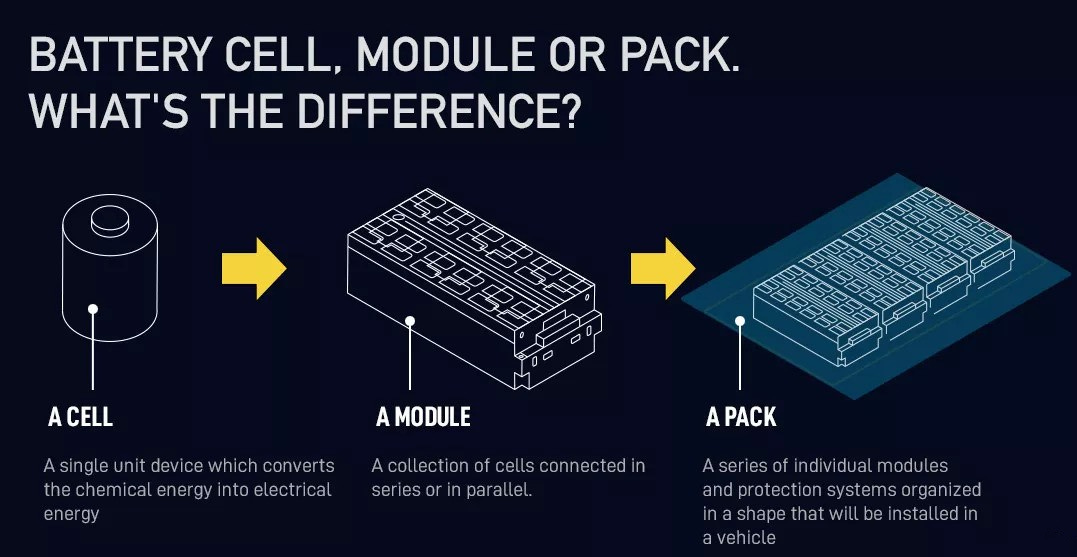

That’s all a cell is — a tiny thing that stores chemical energy which is converted into electrical energy when needed.

Now, a single cell won’t take you very far. That’s why manufacturers bundle them into modules, and then bundle modules into a battery pack. On top of that sits the Battery Management System (BMS), the software and sensors that keep everything balanced, prevent overheating, and extend life.

You know how there are breakthrough technologies that never see the light of day because there’s no way to scale them for mass consumer use? Batteries work similarly. A new chemistry that works beautifully in a single cell often fails when you scale it up into a pack. Heat builds differently, safety risks multiply, and performance drops. That’s the difference between what’s scientifically possible under lab conditions, and what gets used in day to day lives.

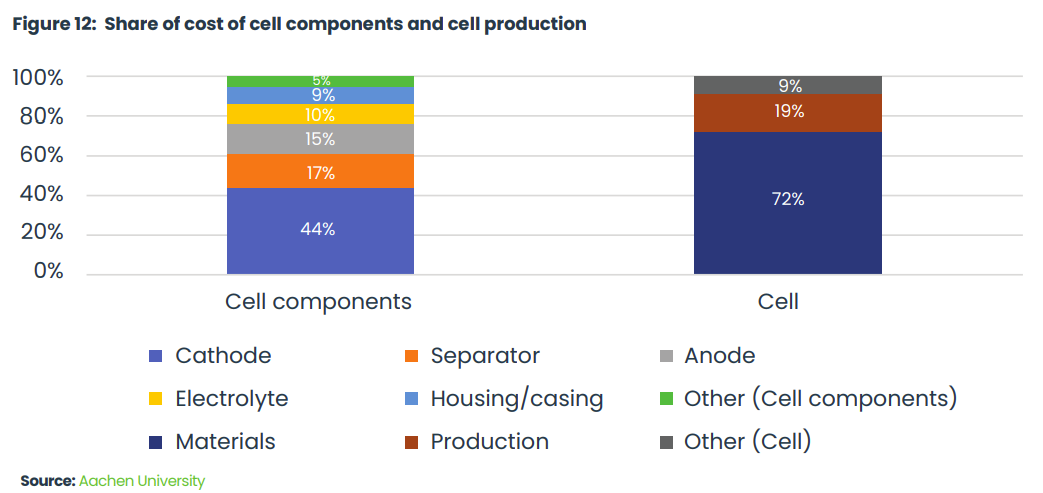

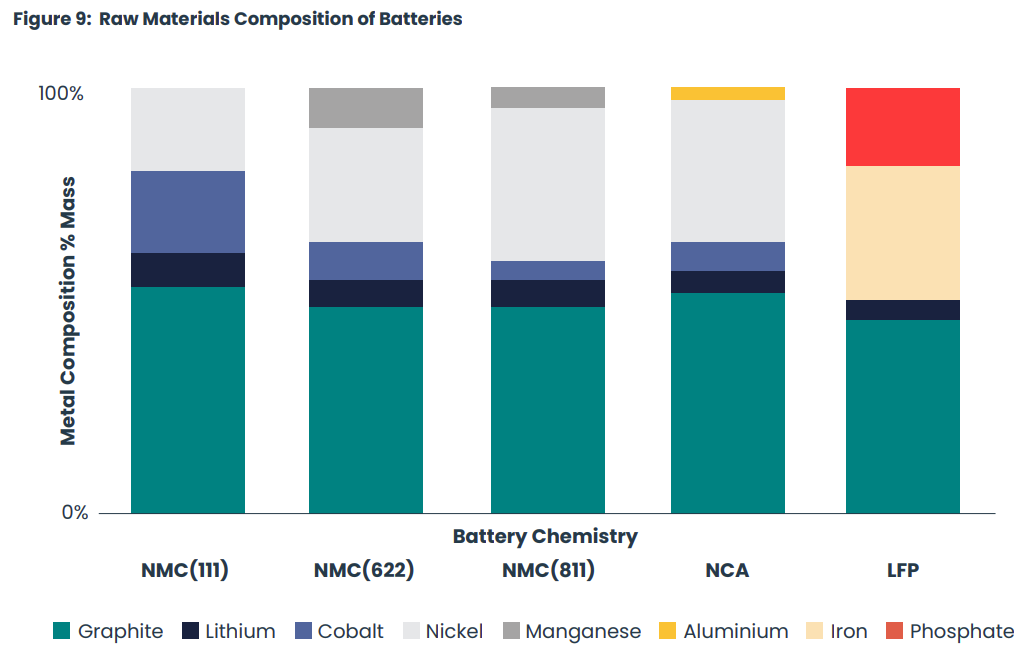

Coming back to cells, here’s how the material costs stack up. The cathode takes the lion’s share — about 40–50%. The anode and separator together account for roughly 15%, while the electrolyte adds another ~10%.

That’s why people in the industry often say: Cathode is king. When we talk about battery chemistry, we’re really asking: what exactly is this cathode made of? Nickel, cobalt, manganese, iron, phosphate — the recipe changes everything.

But it’s not just the cathode. The anode’s material (graphite, silicon blends, or titanate), the electrolyte’s composition (liquid vs. solid), and even the separator’s design all influence how safe, how durable, and how costly the cell ends up being.

The point is this: chemistry shouldn’t be looked at as a choice, but rather a set of trade-offs. The mix you pick decides both battery performance and the economics. Change one ingredient, and you’ve shifted the cost curve, and maybe even which country controls the value chain.

Let’s talk value chain

To understand where the money is made, you have to follow the journey from raw rock to these chemical boxes. Although we covered this in depth in our first primer, here’s a quick revision. The supply chain has four big stops:

First, Upstream

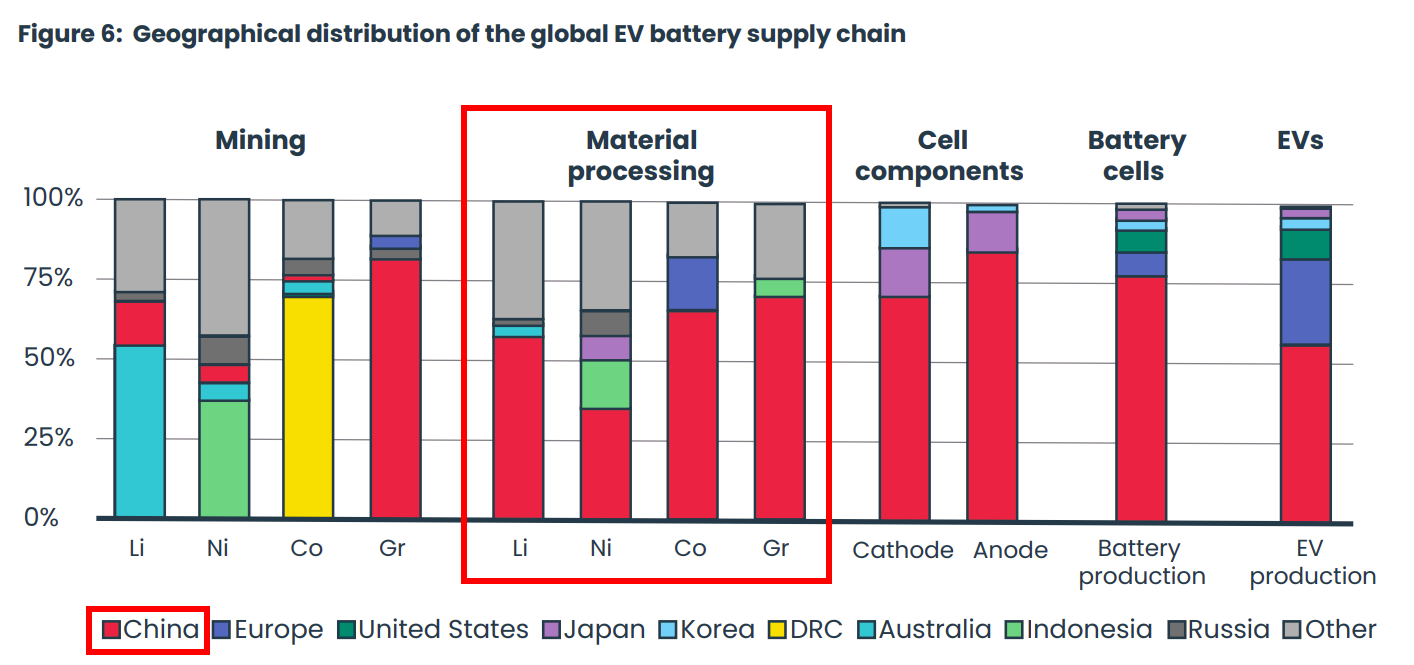

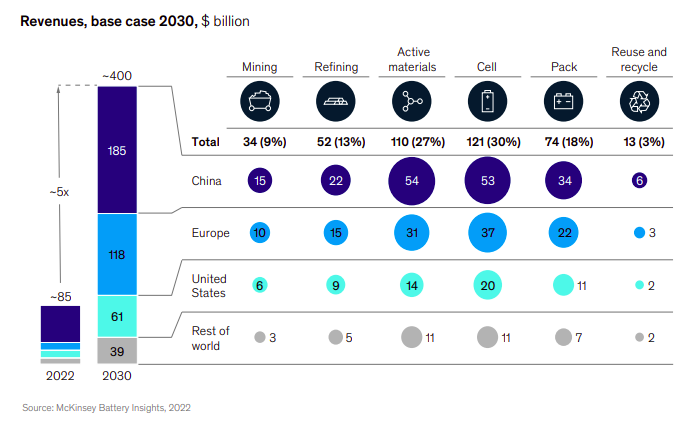

This is mining. Lithium from Australia, cobalt from the DRC, nickel from Indonesia, manganese from South Africa, graphite from China. It’s the dirty, capital-heavy end of the chain. Margins rise and fall with commodity prices, which is great in booms but brutal in busts, showing the cyclical nature of this segment.

Second, Midstream

Here’s where the raw ores are turned into battery-grade chemicals. Lithium carbonate, nickel sulfate, cobalt sulfate — these are the building blocks. This stage is expensive, technical, and dominated by China. And it’s where the real choke points are. You can dig lithium in Australia, but more than half of it still gets shipped to China to be refined.

Third, Cell Components

This is where chemistry comes alive. Companies make cathodes, anodes, electrolytes, and separators, and the formula that decides how they’re arranged. This stage obviously needs a lot of know-how — nothing less than a Masters’ degree — and hence offers better margins.

Fourth, Downstream

Here’s where the physical battery gets built. Cells are made, bundled into packs, wired up, and topped with a BMS. Cell-making is capital-intensive and cutthroat, but the real value sits in smart integration and BMS software. That’s why companies like Tesla spend so much effort here.

The Chemistry Wars

When we talk about “battery chemistry,” what we’re really asking is: what materials sit inside the cell, especially in the cathode?

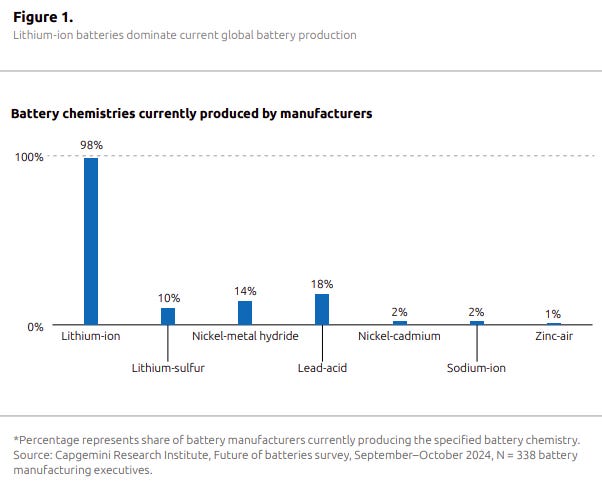

Right now, most of the world runs on lithium-ion batteries — 98% of all battery manufacturers focus on producing these. These use the lithium ions between anode and cathode to store and release energy. But even within lithium-ion, there are several different “recipes”. Each recipe uses different metals in the cathode and comes with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Within lithium-ion, two chemistries dominate the fight today.

The first is lithium iron phosphate (LFP). As the name suggests, its cathode is made of lithium, iron, and phosphate. It’s cheap, stable, and long-lasting — all great benefits. But as we said: chemistry isn’t a choice but a trade-off. And the trade-off in LFP is that it packs less energy per kilogram, meaning cars with LFP batteries need bigger packs to go the same distance.

Despite that, LFP is actually the favorite for mass-market electric cars and for stationary energy storage, because safety and cost matter more there than ultra-long range.

The other camp is nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) and nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA). Here, the core of the cathode is nickel, mixed with some cobalt, and manganese or aluminum added for balance. The result is much higher energy density — these batteries let cars travel longer distances without adding weight. But the catch is cost and supply chain risk: cobalt is mined mainly in Congo under unstable political conditions, and nickel is dominated by Indonesia. These batteries power the premium end of the market — long-range Teslas, BMWs, and Volkswagens.

Then there are the next-generation challengers. Sodium-ion batteries are cheaper and safer but less energy dense, making them promising for grid storage and low-cost EVs. Solid-state batteries swap the liquid electrolyte for a solid material — meaning higher energy density, faster charging, and much better safety. But they’re still expensive and hard to scale. And finally, lithium-sulfur batteries are light and cheap, but degrade too quickly to move from mere lab curiosity to commercial use.

What’s important here is that each chemistry shifts the economics of the entire value chain. If NMC wins, cobalt and nickel miners are the ones who cash in. If LFP wins, iron and phosphate producers take center stage, with China firmly in control. If sodium-ion or solid-state break through, the winners could be completely different players.

The answer isn’t obvious. Over the years we have seen clear evolution in choice of battery chemistry. With changing priorities, newer discoveries and supply bottlenecks, it’s hard to take a bet.

That’s why battery chemistry is as much an investment thesis as it’s a science contest. The choice of chemistry is the strategy that decides who captures the future.

The use case of chemistry matters

When people ask, “Which battery chemistry will win” they’re usually looking for a single answer. But the truth is more nuanced. Each type shines on some counts and stumbles on others.

The things investors and engineers should care about boils down to five expectations (non exhaustive): how much energy a battery can pack into a small space (energy density), how long it lasts (cycle life), how safe it is under stress, how quickly it can charge, and the cost per unit of energy. Obviously, no chemistry scores top marks on all five. That’s why the “winner” always depends on the use case.

For electric vehicles, density and cost are crucial. Premium cars like the Tesla Model S lean on chemistries such as NMC or NCA, which pack in more energy and give you long range. On the other hand, mass-market EVs use LFP. It doesn’t take you as far, but it’s cheaper, safer, and lasts longer, which is exactly what most buyers care about.

In grid storage, the equation flips. Energy density hardly matters when the battery sits in a warehouse next to a solar farm. What matters is safety, durability, and cost. That’s why LFP dominates here too, and why sodium-ion and flow batteries are gaining interest — they’re cheap, stable, and can cycle thousands of times.

For consumer electronics, compactness is everything. Nobody wants a phone that weighs like a brick. So chemistries with high density, like NMC or NCA, still rule laptops and smartphones, even if they’re more expensive and less safe.

And for heavy-duty uses — buses, trucks, military vehicles — the story changes again. These need ruggedness and fast charging more than light weight. That’s where niche chemistries like LTO, which can charge in minutes and last tens of thousands of cycles, make sense.

The Investor’s Lens

So the lesson is this: chemistry follows the job. There is no one winner. The “best” battery is simply the one that matches the expectations of its market. For investors, that means chasing the chemistries aligned with the biggest and fastest-growing applications — because that’s where the real value will be captured.

Quite naturally, chemistry is what decides who gets paid. Batteries might be the new oil wells. But you still need to figure out a way to drill the oil well efficiently. And that’s precisely what chemistry does.

To quote Walter White from Breaking Bad, “The chemistry must be respected”.

How US tariffs are putting pressure on Indian textiles

The threat of US tariffs has been looming over India. But even within that, certain industries are far more threatened than others — textiles is one of them.

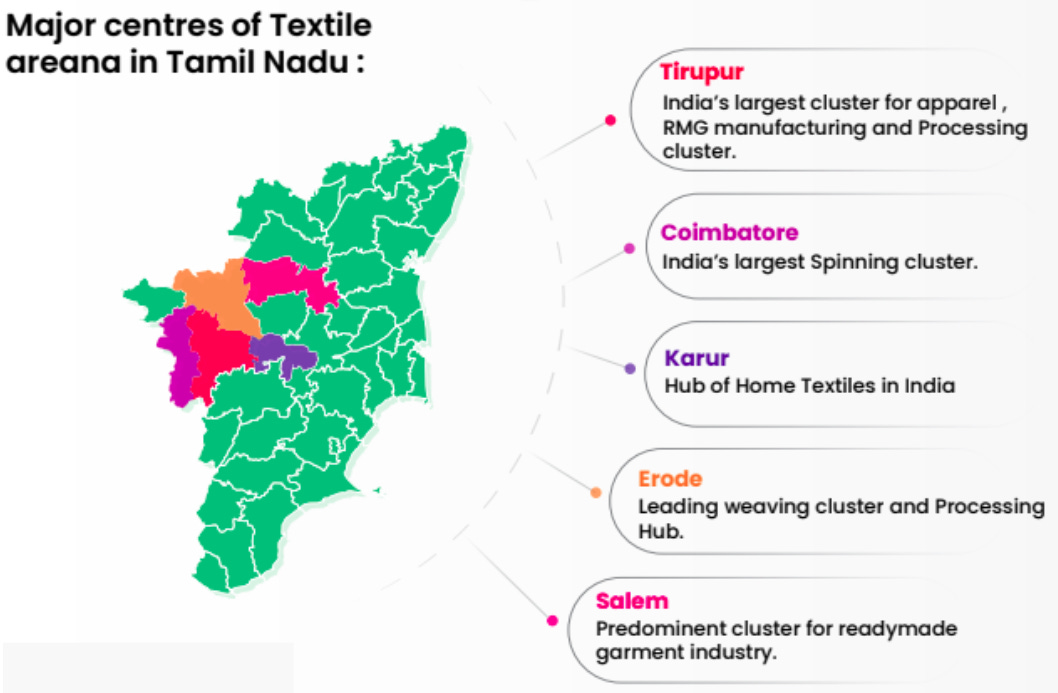

Textiles is the nation's second-largest employer in India. 45 million Indians wake up each day to work in textile factories, spinning mills, and garment units across the country — from the cotton fields of Gujarat to the buzzing factories of Tiruppur, Tamil Nadu. Nearly 80% of this massive industry runs through MSMEs—family businesses, local workshops, small factories—where a single policy change can mean the difference between prosperity and poverty.

India is the world's sixth-largest exporter of textiles and apparel, commanding a 4.1% global market share with $34.4 billion (₹3.03 lakh crore) in exports in FY2023-24. The US buys $10.5 billion (₹92,505 crore) worth of Indian textiles annually, making up 30% of all India's textile exports.

Now, at first, the US imposed a primary tariff on us, but just recently a secondary tariff wall was also applied — with the effective rate now being 50%. This tariff is bound to severely impact not just employment in Indian textiles, but also how the global textiles trade works.

Let’s dive into how tariffs are affecting Indian textiles.

How India exports textiles

Before we get into the structure of India’s textiles exports, there’s a distinction to be made in what makes up textiles.

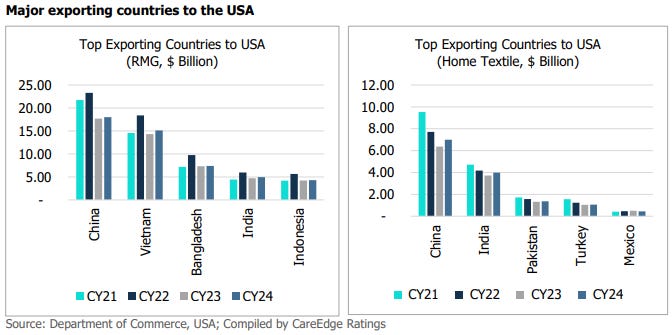

Many analysts divide garments into two categories: ready-made garments (RMG) and home textiles. RMG is all the clothes that we wear — shirts, pants, trousers, jeans, skirts and so on. Home textiles, on the other hand, are things like curtains, bed-sheets and sofa covers.

Both goods also have different types of demand. Garments are extremely fast-moving with short order cycles, as fashion trends change quickly with seasons and other factors. They’re also higher-value products compared to textiles, as it’s harder to transform a given amount of cotton into clothes versus home textiles. As a result, production of RMG is also far more labour-intensive.

Home textiles, on the other hand, have predictable demand, and they’re often tied to trends in housing and real estate. Orders for home textiles often entail long-term contracts with retailers like Costco and Target. They’re not subject to rapidly changing, seasonal trends like in fashion.

The composition of India's textile exports to the United States reveals a specialised focus on cotton-based products that have long been the country's strength. RMG dominates this trade, accounting for $5.18 billion (₹45,615.8 crore) — a 51% share — of textile exports to the US. Home textiles make up $3.79 billion(₹33,419.9 crore) (37%). The remaining 12%, valued at $1.23 billion(₹10,836.3 crore), consists of yarn, fabric, and other textile products.

What also matters is how Indian exporters sell textiles products. They operate on very tight margins with pre-booked orders — they have very little room to set prices themselves, especially with US buyers. Textiles also face long lead times — the time taken from sourcing to production to delivery. And at each step of the lead time, exporters need loans at each step of the way — the collateral for which comes from future orders, inventory and receivables.

Now, imagine if you’re such an exporter, and your upcoming orders are cancelled due to tariffs. You’ll now find it incredibly hard to repay these loans, and you might even be forced to shut your operations overnight.

Falling down the global trade order

This tariff will also fundamentally alter the competitive equation of global textiles trade.

Pre-US tariffs, the competitive landscape in textiles was already fairly stark. China (also the largest exporter of textiles in the world) is the largest exporter to the US in both RMG and home textiles. Vietnam follows next, exporting $16 billion (₹1.4 lakh crore) worth of all textiles (most of it RMG) to the US in 2024 — a little over half of what China sells. India is third at a total of $10.5 billion (₹92,505 crore)worth of both RMG and home textiles sold to the US.

But the tariffs, which have been unevenly applied on different countries, are making life for India even harder. While China is subject to a 30% tariff, and Vietnam 20%, India is slapped with 50%, higher than most of our peers. Close US allies with trade agreements— Japan, South Korea, and the EU—enjoy tariff ceilings near 15%. Other regional exporters like Indonesia (3% market share) face roughly 19% US tariffs, while Mexico has duty-free access under the USMCA.

As our cost advantage has now evaporated, our exports (both RMG and home textiles) have become deeply uncompetitive. This has also resulted in a re-routing of world trade — rival suppliers in Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Indonesia are receiving diverted orders as US buyers seek to avoid India's tariff costs. Turkey—known for quality towels and rugs—faces lower duties, making it instantly more competitive.

But that’s not all. With the world’s richest market closed down, leading exporters like China will have to find new avenues for their goods. This could potentially cause an over-flooding of foreign textiles in India. To some extent, this was already happening and Indian firms were expressing their concerns over it. But the tariffs could further amplify this problem.

The world’s market share distribution in textiles is now poised for what could potentially be a dramatic realignment.

Tamil Nadu: The Epicenter of Impact

No state in India feels the tremors of these tariff changes more acutely than Tamil Nadu.

The state accounts for 28% of total employment in the country's textile manufacturing sector and produces 20% of India's readymade garments — highest among all Indian states. The state houses major textile hubs, including Tiruppur for knitwear garments, Coimbatore for textile mills and yarn/fabric production, and Karur for home textiles. The industry provides livelihoods to an estimated 7.5 million people in the state.

Chief Minister M.K. Stalin wrote to Prime Minister Narendra Modi that 3 million jobs in Tamil Nadu could be at immediate risk. The state government estimates a potential export loss of $3.93 billion (₹34,713.3 crore) in 2025-26, with the textile sector alone accounting for $1.62 billion (₹14,282.2 crore) of this projected decline.

Tiruppur, being the biggest exporter of textiles from India, faces an unprecedented crisis under the new US tariff regime. ₹12,000 crore worth of garments from Tiruppur are exported to the US annually. The city accounts for 90% of India's cotton knitwear exports and 55% share in India’s total knitwear exports. It provides direct or indirect employment to over 9 lakh people, with 2,500 exporter firms and 20,000 smaller supporting units forming the ecosystem.

With over 30% of Tiruppur's output shipped to the US market, the 50% tariff strikes at the core of its business model.

The Tiruppur Exporters’ Association (TEA) has stated:

“We were hopeful that next year’s business would increase by up to 20% compared to the current year. But due to Trump’s new tariff policy, we cannot reach the expected target if the situation continues for the next two months because 30% of the exports are to the US. This has caused a major impact on our exports. American companies have asked us to halt some already-taken orders. New orders are also not being placed.”

The cost structure makes absorption impossible. Tiruppur's exporters operate on thin margins of 5% on US deals, leaving no room to absorb a 50% tariff that raises the landed prices by an estimated 30-35%.

This immediate shift in the trade order threatens Tiruppur's long-term market position, as buyers typically maintain new supplier relationships once established, making it difficult to regain lost business even if tariffs are eventually lifted.

Indian firms, and the government, try to adapt

Well, how are Indian companies adapting to this new paradigm?

For one, we’re trying to find new outlets for not just our goods, but also our textiles factories. Gokaldas Exports, for instance, has mentioned Africa as an advantageous place to be in its latest earnings call — the tariff on both Kenya and Ethiopia is 10%. They have also encouraged several customers to seek African production.

Before Trump announced the new secondary tariffs, companies were already afraid they couldn’t absorb the older rates which are already big — and neither can their B2B customers. The brands are thinking about passing on some or all of the extra costs due to the tariffs to the consumers. And there are two ways to do this:

Through straight price hikes, or

Shrinkflation — make the garments cheaper-quality by using lighter fabrics, fewer stitches, simpler trims etc, but charge the same amount

The Indian government is helping, too. It is extending the duty-free import of cotton by 3 months, so that manufacturers face lower raw material costs. It has also planned dedicated outreach programs in 40 countries—including Australia, the EU, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, and the Gulf. It represents over $590 billion (₹52.08 lakh crore) in textile and apparel imports where India currently holds a small market share.

However, the demand profile of some of these countries may not match what India is already good at. The EU, for instance, mostly uses synthetic fibers and yarns. India, on the other hand, while being the 2nd-largest producer of cotton, has a very low share (9.2%) of synthetics in its exports. Diversification won’t be as simple as merely reaching out — India will require boosting its capabilities to make synthetics.

But that’s not the only bottleneck in diversification. Often, textile manufacturers might not be able to sell the already-manufactured garments for US customers to a different buyer because the US customer owns a license for the design and style.

The government is also planning on launching a relief package for Indian exporters. However, this will involve an extra expenditure that will eat into the state budget, increasing the fiscal deficit.

What next?

If the 50% duty remains in force for an extended period, early projections suggest India's total exports to the US could plummet from about $86-87 billion (₹7.58–7.66 lakh crore) (2024) to only approximately $50 (₹4.41 lakh crore) billion in 2026. And textiles will inevitably make up a big chunk of it.

Indian manufacturers face limited options for absorbing such costs or quickly finding alternative markets. Some larger companies might consider establishing production facilities in countries not facing the tariff, manufacturing via Bangladesh or Vietnam subsidiaries to fulfil US orders indirectly.

India is at a crossroads right now. Manufacturers and exporters are scrambling to find an outlet for our goods, but at the same time, so are other countries. The world risks being over-flooded by textiles, which could damage the Indian textiles industry and affect millions of livelihoods.

The Indian textile industry's resilience will be tested as never before.

Tidbits

Govt Eases MRP Revision Rules Amid GST Changes

The Centre has permitted FMCG firms to revise MRPs on unsold stock using stickers or stamping in line with new GST rates, while keeping old MRPs visible. Companies can use existing packaging until December 31, 2025. The move, welcomed by industry, reduces wastage, eases compliance, and ensures price changes only reflect GST revisions

Source: The Hindu BusinesslineED Attaches ₹186 Cr Assets in DHFL Fraud Case

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) has attached assets worth ₹186 crore in the DHFL bank loan fraud case under PMLA. The assets include 154 flats and receivables from 20 Mumbai properties. Promoters Kapil and Dheeraj Wadhawan allegedly siphoned funds through proxy firms to rig DHFL’s stock price. The case stems from a CBI FIR accusing DHFL of cheating a consortium of 17 banks led by Union Bank of India

Source: Economic TimesBanks Push RBI to Extend G-Sec Issuances Amid Surplus Supply

Commercial banks have urged the RBI to extend central government bond issuances into March 2026, instead of ending them in February, to ease pressure from heavy weekly supplies. They also want all state bond auctions shifted to a uniform pricing method, arguing it would compress spreads in a high-supply, low-demand environment. This comes as an oversupply issue caused bond yields to rise.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Vignesh

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

Checkout Points and Figures

This is our way of breaking down what India’s leading companies are telling their shareholders and analysts. We go through the investor presentations, pull out the charts and data points that actually matter, and highlight the signals behind the numbers—whether about growth plans, margins, new markets, or risks on the horizon.

Check it out here

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉