Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna.

For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about. The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

For all the sources mentioned in this video, don’t forget to check out our newsletter; the link is in the description.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Moving up the value chain ft. EMS companies

Some of the largest EMS companies in India seem to be making the same bet. They’re spending hundreds to thousands of crores to move on from being mere assemblers and start making components or trying to move ahead in the value chain.

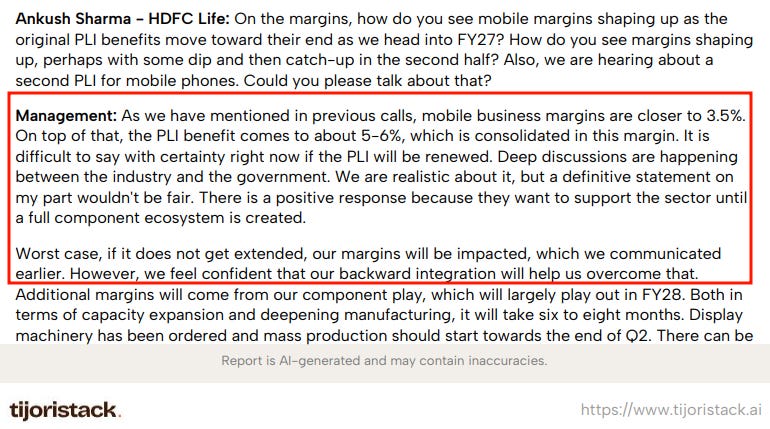

The logic is straightforward. If you’re just assembling phones or medical devices or industrial equipment, you’re taking components made elsewhere, putting them together, and earning a thin service margin. Dixon’s CFO laid out the economics plainly:

“Mobile business margins are closer to 3.5%. On top of that, the PLI benefit comes to about 5-6%, which is consolidated in this margin.” Take away the government incentive, and you’re left with brutally thin margins on a business that depends entirely on component prices you don’t control and customer demand you can’t predict.”

[Before I go ahead, just a quick tidbit. I went through all the concalls on Concall Monitor by Tijori. Our team uses it to track concalls as soon as they’re released, speeding up research times and even generating a quick sector report. Do check it out if you are an active investor.]

So the only way out is backward integration. Make the components yourself - displays, camera modules, printed circuit boards. Capture more of the value chain, improve margins, and reduce import dependence. Dixon’s management put it this way:

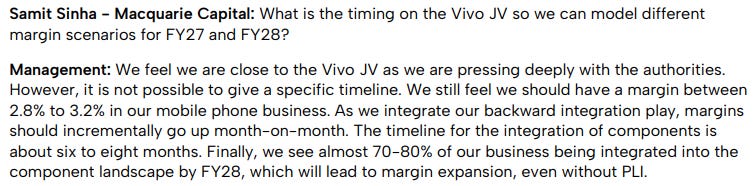

“Finally, we see almost 70-80% of our business being integrated into the component landscape by FY28, which will lead to margin expansion, even without PLI.”

That “even without PLI” bit matters. PLI is propping up margins right now, and there’s uncertainty about whether it will extend beyond FY27. But the good news for the industry is that in the recent budget, the allocation for component manufacturing was increased to ₹40,000 crores in the latest budget.

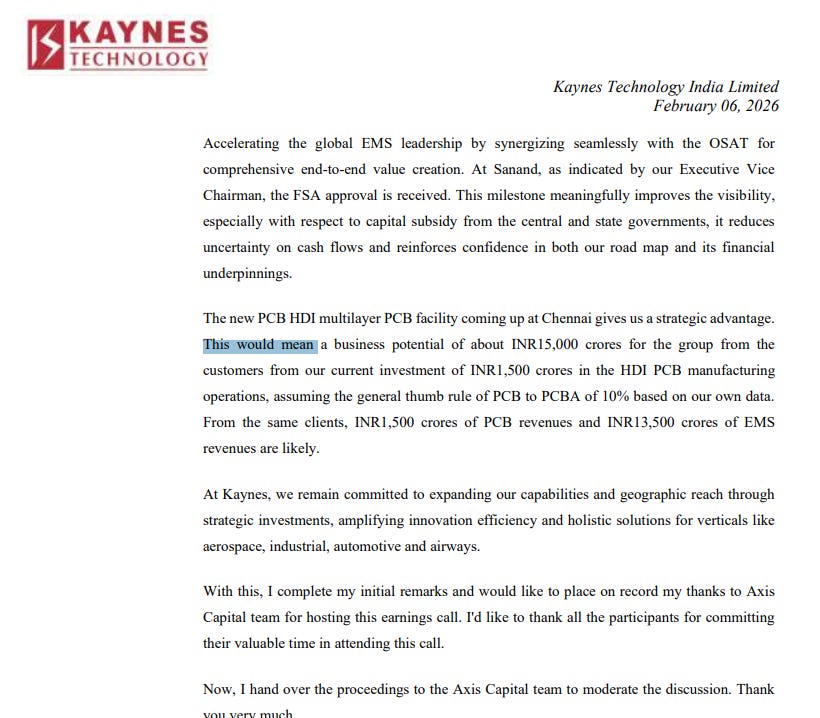

Kaynes is making an even more explicit pitch. Their CFO explained:

“This would mean a business potential of about INR15,000 crores for the group from the customers from our current investment of INR1,500 crores in the HDI PCB manufacturing operations, assuming the general thumb rule of PCB to PCBA of 10% based on our own data. From the same clients, INR1,500 crores of PCB revenues and INR13,500 crores of EMS revenues are likely.”

The logic is that if you make the PCB, you win the contract to assemble the full product. One pulls the other. It’s not just margins on the PCB; it’s the EMS business that follows.

Syrma’s MD echoed the same thing:

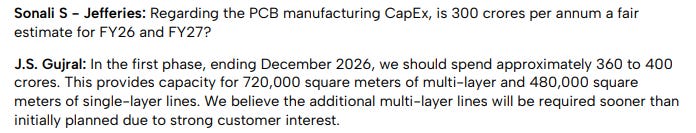

“In the first phase, ending December 2026, we should spend approximately 360 to 400 crores. This provides capacity for 720,000 square meters of multi-layer and 480,000 square meters of single-layer lines. We believe the additional multi-layer lines will be required sooner than initially planned due to strong customer interest.”

Customer interest is the key phrase there. It suggests customers actually want them to make these components, which means more business is on the table if they can deliver.

The capex isn’t small. Dixon is putting ₹1,100–1,200 crore into display manufacturing and scaling camera modules from 40 million to 190–200 million units annually. Kaynes is committing ₹1,400 crore for PCB manufacturing and ₹1,700–1,800 crore for OSAT, plus ₹250–300 crore on camera modules. Syrma is investing ₹360–400 crore in the first phase of its PCB plant.

But here’s the thing. All of this is supposed to pay off in FY28. Dixon’s management said it explicitly:

“Additional margins will come from our component play, which will largely play out in FY28. Both in terms of capacity expansion and deepening manufacturing, it will take six to eight months.”

Kaynes said almost the exact same thing. But the timelines keep moving. Dixon’s display JV with HKC was supposed to start trials in Q4 FY26. Now that’s pushed even further. These things take longer than expected, and that’s normal in manufacturing, but it does mean the margin improvement story keeps getting pushed out.

There’s also a genuine external shock hitting some of these companies, particularly Dixon. Memory prices have spiked because of what’s happening in AI. We wrote about this at length in one of our earlier Daily Brief piece. Dixon’s MD gave the clearest explanation:

“The potential cutback in smartphone shipments comes as brand struggle with an unfolding super cycle in the global memory sector. Top suppliers are shifting capacity for large intelligent applications, resulting in a supply squeeze for the smartphone segment.”

AI and data centers need massive amounts of memory chips. Memory manufacturers are redirecting supply away from consumer electronics to serve that demand. The result is memory prices for smartphones have shot up significantly over the last two quarters.

And here’s why that’s a problem for someone like Dixon:

“Memory has moved from being a relatively small line item to one of the most sensitive parts of the bill of materials, especially for lower-priced devices.”

If memory prices spike, companies face a choice—absorb the cost or pass it on. Dixon says the cost is a pass-through for them, but higher phone prices can hurt demand in the lower and mid-tier segments where they operate.

Strip it down, and the story is this: India’s EMS companies know assembly alone cannot carry them very far. The margins are thin, the bargaining power is limited, and the comfort of PLI will not last forever. Moving into components is not an optional upgrade; it is an attempt to change the structure of the business itself — to own more of the product, earn more per unit, and rely less on incentives.

But this shift comes with heavier capital, longer timelines, and far less room for error. Component manufacturing demands scale and steady demand to justify the investment, and both depend on forces these companies still do not fully control.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Sector rotation 😊