What happens if your bank fails?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Does India need higher deposit insurance?

The economics of air pollution

Does India need higher deposit insurance?

Banks, at their very core, run on one simple concept: trust. Every time you hand over your money to a bank—whether as a simple savings account or a fixed deposit—you do so believing that your money will be safe. This trust is precisely what makes banks' business models work. This trust allows banks to acquire capital, which they can then utilize to facilitate trade, extend credit, or carry out a variety of other operations.

But there’s a flip side. As soon as that trust takes a hit — be it from rumors, fraud, or a high-profile failure — people rush to withdraw their money in a flash. After all, if a bank can’t give back everyone’s money, anyone who waits for too long will be left without any money at all. That’s when the system trembles under the weight of a bank run. This is why it’s absolutely crucial to protect that trust.

Recent history offers some stark cautionary tales. Two such instances, though on different scales, were the mishaps at PMC Bank in India and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the United States. We won’t get into the details of these events. However, both episodes showed how depositor anxiety can instantly snowball into a panic, causing a run on the bank.

In our hyperconnected age, a single social media post can spark swift deposit flights, sometimes outpacing regulators. Even if a bank’s finances are largely stable, panic alone can tip it into crisis. And given how inter-connected banks are, even if one bank goes down, that can challenge the stability of the whole banking system.

So, how do we maintain that trust?

Enters deposit insurance

Whenever trust in a bank shakes, one of the strongest safety nets is deposit insurance. Basically, there’s a third-party entity that promises that you’ll get at least some of the money stored in your account, even if a bank collapses.

This guarantee is usually given by a specialized institution — usually state-backed. In India, this is done through the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC). This insurance is funded by premiums that banks themselves pay. Though these premiums might feel invisible to depositors, they make a world of difference when times get rough.

Research consistently backs the stabilizing effect of deposit insurance. A 2017 study titled “The Importance of Deposit Insurance Credibility” shows that credible insurance shields banks from panic runs, but only if depositors truly believe the insurance can and will pay out. If depositors lose faith in the insurer’s ability to keep its promise, the calming effect wanes. This is why depositors’ insurance needs to toe a fine line: it needs to be both robust and believable.

In India, conversations around deposit insurance have recently surged again, after irregularities surfaced at New India Cooperative Bank. Suddenly, depositors, especially smaller savers, and senior citizens started paying closer attention to whether their deposits would be returned if the bank went under. All this reaffirms what experts have long said: deposit insurance is crucial not just for depositor peace of mind but also for the stability of the wider banking ecosystem. Without it, any whiff of trouble causes panic and a self-fulfilling downward spiral.

How did it all start?

India’s deposit insurance journey began in 1962 — with the Deposit Insurance Corporation (DIC). The DICGC came into its current form in 1978, when the DIC was merged with the Credit Guarantee Corporation of India.

Interestingly, India was the second country in the world, after the United States (which established the FDIC in 1933), to institute such a protective mechanism. Over the decades, deposit insurance coverage in India has steadily climbed higher.

By 2020, depositors enjoyed coverage up to ₹5 lakh per depositor per bank.

According to a CareEdge report, currently, while 97.8% of all deposit accounts in India fall under this deposit insurance coverage, they represent only about 43.1% of total assessable deposits (FY24 figures). Put simply, most banking customers — by headcount — are fully covered, because a vast majority of people have modest balances. However, the overall amount insured is still less than half of the total deposits in the system. Those with more money in their accounts are vulnerable to a default.

So, should the limit go higher to cover more deposits? The Deputy Governor of the RBI, Mr. M. Rajeshwar Rao, in a recent speech hinted at this:

“Considering multiple factors like growth in the value of bank deposits, economic growth rate, inflation, increase in income levels, etc., a periodical upward revision of this limit may be warranted”

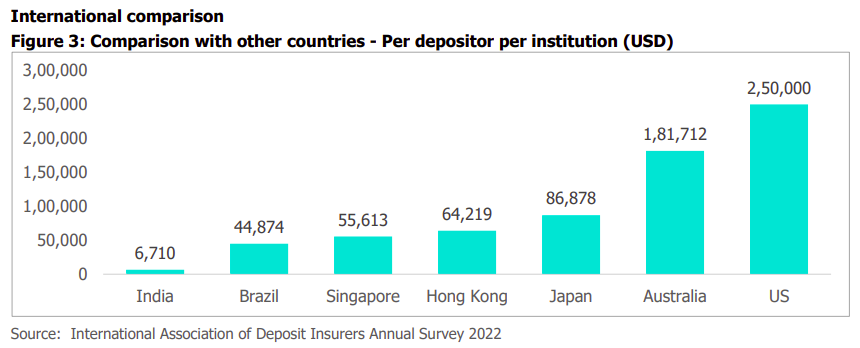

Moreover, international comparisons from a CareEdge study show that in purely dollar terms, our coverage still looks modest next to countries like the U.S. or Australia, where insured amounts stretch into six figures (in USD).

Of course, a direct apples-to-apples comparison between countries can be misleading due to differences in purchasing power, currency values, and socio-economic contexts. But it does emphasize that the debate in India—whether ₹5 lakh is enough—should remain open.

What’s the right insurance amount, then?

The CareEdge report outlines four approaches for estimating the appropriate deposit insurance limit for India. These involve:

Global Benchmarks: Citing the International Association of Deposit Insurers, which recommends targeting around 80–90% of all accounts and roughly 20–30% of the total deposit value. India already covers nearly 98% of accounts, so strictly by that metric, no change might be needed.

Historic Coverage vs. Per Capita GDP: One could evaluate the ‘correct’ deposit insurance limit as a multiple of per capita GDP over the years. Historically, this ratio was much higher for India. If we replicate past ratios to current per capita GDP, an even higher insurance limit might be warranted.

Source: CareEdge Inflation Adjustment: Money loses value over time. By placing a single fixed limit of ₹5 lakh, essentially, you’re ensuring that the amount insured is less and less valuable with time. To get around this, one could take the last revision (2020) and simply adjust it for inflation. This approach suggests a more incremental increase in the insurance limit, pushing the coverage slightly higher every year.

Cross-Country Comparisons: One could try benchmarking India’s deposit insurance against countries like the U.S., Japan, or Australia — based on their relative per capita GDP. While overall, these numbers show India’s coverage is fairly average, they don’t necessarily capture local context — like India’s deposit profiles or per capita income.

Source: CareEdge

Crucially, none of these is a “perfect” formula formula. Each is simply a lens to view the issue. All these approaches are subject to one’s assumptions about risk tolerance, fiscal space, and depositor behavior.

Now, raising the coverage limit is often called vertical expansion—i.e., how high the coverage per depositor goes. But, as Mr. Rao noted, the debate can also shift horizontally to which types of institutions and “deposit-like” products get insured. People no longer just lean on bank deposits to store their spare money. With financial technology evolving — think digital wallets, fintech offerings, or liquid funds — there’s a question of whether these new forms of balances should also fall under the deposit insurance umbrella.

But why not insure everything?

Now, countries like Uzbekistan have unlimited coverage. That means, all the deposits in the banking system are insured. Isn’t that… perfect? Why accept any loss at all?

For one, of course, that can simply mean a giant liability for the DICGC — where public money will be used to fix the mistakes of private bankers. While it isn’t ideal that people lose their money, this arrangement isn’t ideal either.

There’s one thing that makes this problem worse — a persistent worry with generous deposit insurance is what economists call a ‘moral hazard’. If depositors know their money is fully safe regardless of the bank’s risk-taking, customers may ignore red flags in what banks are doing, allowing them to act recklessly. This is why a balance must be struck: you need coverage high enough to protect the vulnerable and prevent system-wide runs, yet not so high as to encourage banks to take irresponsible risks.

One suggestion, again mentioned in the RBI Deputy Governor’s speech, is to tailor higher coverage for certain demographic groups, such as senior citizens, rather than doing a blanket hike that may primarily shield large-scale depositors.

It’s not a free lunch

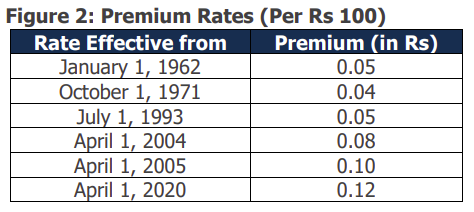

Deposit insurance is not free. Banks pay a premium on every ₹100 of deposits, and that cost can indirectly pass on to customers (through slightly lower interest or higher fees). As per the data, India’s deposit insurance premium—once as low as ₹0.05 per ₹100—had climbed to ₹0.12 as of 2020.

Most countries, including India, use a flat premium: each bank pays the same rate. But around 55% of deposit insurance systems globally use a risk-based premium, charging riskier banks more.

When all banks pay the same premium, deposit insurance is often lop-sided. If everyone pays the same costs, in essence, the best-run banks subsidize poorly run banks. Many argue that this status quo is unfair and may even reinforce complacency. This is why multiple committees (e.g., the Narasimham Committee, Capoor Committee, and others) have long recommended moving to a differential premium system. Yet, it hasn’t been adopted.

Data shows that while commercial banks pay a hefty bulk of premiums (94.4% in FY24), most payout events arise from cooperative banks. This mismatch only intensifies calls for a risk-based system so that riskier institutions bear greater costs.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The deposit insurance debate is a tightrope walk:

Too little coverage and panic can erupt the moment a bank wobbles, undermining financial stability.

Too much coverage can breed moral hazard, draining public coffers and letting weak banks thrive on easy money.

There is no consensus “right number.” There are many options on the table — from increasing coverage to indexing coverage to inflation, to selectively providing more coverage for especially vulnerable groups. The key is to preserve the system’s central goal: keeping depositor confidence high without discouraging prudent banking.

In a world where information (and misinformation) spreads at breakneck speed, deposit insurance is an anchor. It gives people the reassurance that their savings have a safety net, preventing the kind of all-out runs that have failed entire institutions. However, it’s important to refine this system—whether by carefully raising limits, applying risk-based premiums, or expanding the coverage to new channels—without losing sight of balance. After all, while you need to build trust in the system, blind trust helps nobody.

The economics of air pollution

Here’s some interesting, if sad, news that we recently came across: Insurance companies are thinking of hiking health insurance premiums for residents of New Delhi by 10-15%. Apparently, the number of claims they received last winter for respiratory illnesses and other air pollution-related problems was simply too high. For the first time, insurers are now thinking of treating pollution levels as an important factor when determining premiums. Living in Delhi, in other words, is now a co-morbidity.

There’s a regulatory hurdle here: IRDAI (Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India) will have to approve this linkage. For that, insurers will need to present strong evidence linking pollution levels to increased claims. Given the overwhelming impact of pollution on health, however, this doesn’t seem too difficult.

But this is just one more illustration of a problem that is much bigger than insurance premiums. As we covered last week, environmental degradation has immediate, monetary consequences. We aren’t talking about abstract projections of what climate change will do decades from now — there are direct ways in which these issues are hitting your own wallet right now, even if you don’t feel a direct impact on your health.

Our disgusting air

India’s air pollution levels are among the highest in the world. It’s frankly one of the worst assaults on our immediate environment. Every single Indian — all 1.4 billion of us —- is exposed to unhealthy levels of PM 2.5 pollution, which are the very particles that cause the most damage to one’s health.

In fact, we don’t even completely understand the scale of our challenge: most studies on the health impacts of air pollution come from America and Europe, where air pollution is a fraction of what it is in India. Consider this — Delhi’s AQI in winter months is routinely close to 100 times the WHO’s maximum recommended limit. We have relatively little research that accurately measures the impact of this sort of extreme air pollution on our health and economy.

While this has a direct impact on our health, it also hurts our economy. How big an impact? Well, so much of the math here is speculative that it is impossible to arrive at a specific number value. There are many assumptions involved in such an exercise, which you can fight over endlessly. That said, even directionally, this impact would be huge. Some estimates, in fact, point to a yearly GDP loss of nearly a hundred billion dollars every year.

Think about that for a second. The COVID-19 pandemic — our worst health crisis in a century — led to a combined loss of ~$220 billion. Roughly speaking, every two years, air pollution drains the Indian economy of the amount of value we lost in the entire COVID-19 pandemic.

The first-order effects of pollution

Let’s look at how, precisely, air pollution affects the economy. This is a complicated question — pollution comes in many forms, and there are layers and layers to the impact it has. But here are the most immediate effects it has.

Mortality and morbidity

The most direct and devastating effect of air pollution is its impact on human health. It causes a wide range of illnesses, including heart disease, respiratory infections, and strokes.

Millions of people die from these conditions every year. In 2019 alone — a single year — researchers found that 1.67 million Indians had lost their lives because of air pollution. That’s nearly one in every six deaths in India. Heart-breakingly, more than one in every twenty of these deaths were newborn infants, whose bodies degenerated before they even began their lives.

But death isn’t the possible harm. Many more people are left sick, unable to work, or struggling with chronic conditions. All of this takes a toll on the economy. In 2019, Indians collectively lost 53.5 million healthy years of their lives — what researchers call ‘disability-adjusted life years’ or ‘DALYs’ — to air pollution.

All these people — who either passed away or were knocked out of work — are pushed out of the labour force, which has profound economic consequences. In 2019, the Global Burden of Disease study — one of the most comprehensive worldwide studies on key health issues — estimated that air pollution caused a per capita loss of $ 26.5 for Indians — in other words, every Indian alive loses roughly ₹2,300 a year to air pollution. The hardest-hit states were among India’s poorest, such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Productivity

Even when people aren’t removed from the economy altogether, air pollution has more subtle, intermittent impacts on the economy.

For instance, when air pollution is high, people tend to fall unwell more often. A study in Spain, for instance, found that with every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 levels, worker absenteeism went up by 2% — as people took sick days more often. A study in Bengaluru’s Whitefield — home to many of India’s IT businesses — showed that in winter months, when pollution was high, the number of workers showing up to work was lower by 12%, compared to the summer.

The workers that did show up, meanwhile, were 8-10% less productive. As a result, they had to work for longer hours to compensate. This has longer-term effects on how happy employees are, and how well they can perform.

Businesses suffer too — customers are significantly less likely to frequent markets in times of bad pollution, which hurts sales. The impact is the most evident on outdoor businesses — like retail, or restaurants.

Agriculture

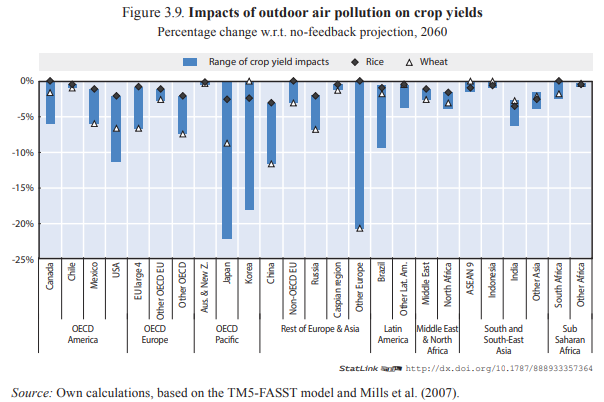

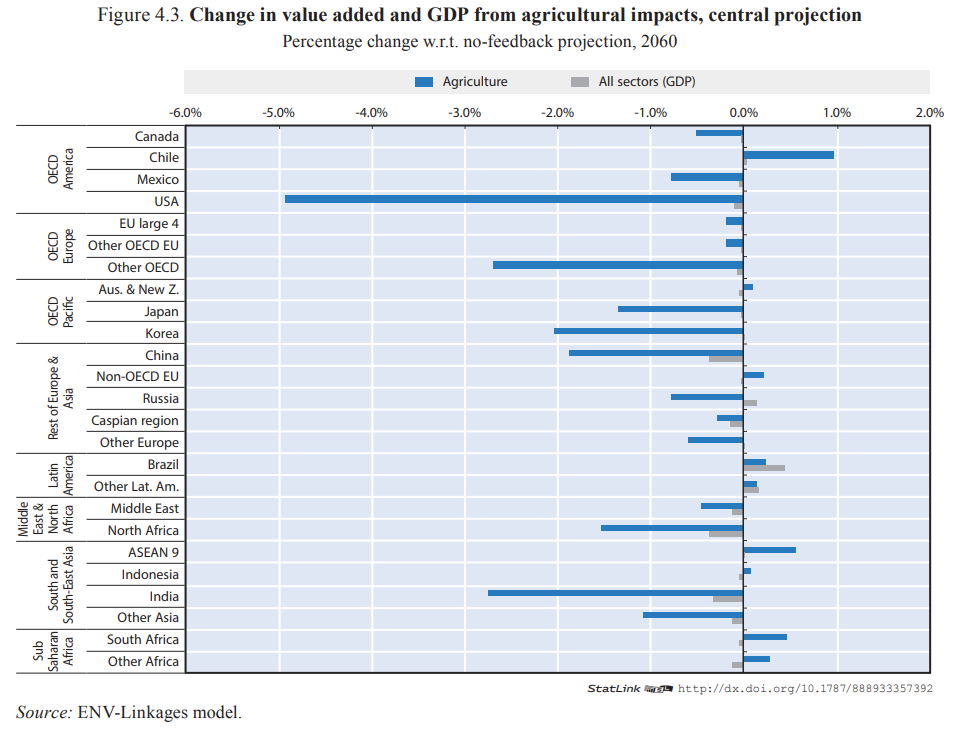

The economic damage of air pollution extends far beyond human health — it directly hurts agriculture as well. One of the key culprits for this is ground-level ozone, which forms when nitrogen oxides from vehicle exhausts react with air.

While ozone is essential for our survival when it’s in a layer in the upper atmosphere, closer to the ground, it’s deeply damaging. It gets into plant leaves and damages their internal structure. Leaves age quickly, or even die, and are less able to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. This hits crop yields severely — reducing their grain size, protein content, and nutritional value. While the impact varies wildly from crop to crop, in general, yields can go down by as much as 15-20%.

Because of this, agricultural productivity suffers. Now, food is always in demand, so the overall food supply doesn’t decline too significantly. But growing that food becomes much more costly. Farming becomes more intensive — farmers have to use more fertilizer and water to grow the same amount of food. This degrades the soil, pollutes water, and has complex knock-on effects on the environment.

This is especially damaging for a country like India, because agriculture makes for a large part of our GDP, while most Indian farmers struggle to get the capital they need for more intensive agriculture.

The hidden second-order effects

These are only the first-order effects of air pollution, however. They’re just the tip of the iceberg.

These direct effects unleash a cascade of indirect effects. For instance, businesses may be forced to restructure their operations. Employees’ productivity can drop, and people may do less outside of work, leading to less vibrant economies. Tourist footfalls go down. Monuments are scarred. Machines corrode faster. Pollution affects the mind, causing cognitive decline and an increase in crime rates.

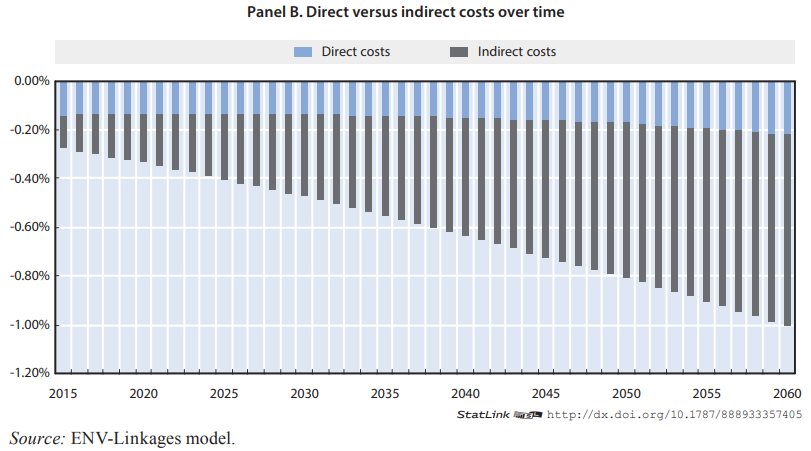

The impact of all these distant effects is much harder to measure, and there are few estimates we found that tried to quantify their impact. Yet, research indicates that these make for the largest impact on our GDP — many times as significant as the direct costs.

These effects can add up in surprising ways. Here’s one particularly curious example: in many of the world’s largest cities — like London, Paris, or New York — the eastern districts tend to be poorer and less developed than the western ones.

The reason? It might simply be wind patterns, one theory suggests. In most of the Northern Hemisphere, winds predominantly blow west to east. As a result, industrial emissions usually flow into cities’ Eastern districts. Over the centuries, these effects have accumulated. There are now stark differences in economic outcomes between the two halves of these cities. Evidently, pollution doesn’t just cause short-term losses — it shapes the long-term development of entire regions.

Is pollution an acceptable cost for growth

There’s a common assumption that reducing pollution must come at the expense of economic growth. To an extent, that is true — pollution is often the direct by-product of industrial and economic activity. But there is nuance here.

Growth may create air pollution, but air pollution, in turn, hurts future growth. For instance, World Bank researchers estimate that if our air pollution had grown at half its rate between 1998 and 2021, our GDP would have been ~4.5% higher by the end of this period.

So, what’s the way ahead? We aren’t sure.

But one thing’s for certain: environmental matters don’t sit in a different category from financial ones. Over at Markets, we believe that everything touches the financial world, once you look keenly enough. If insurers start charging their Delhi-based clients higher premiums, that’ll simply be yet another demonstration of this idea.

Tidbits

KKR is set to acquire 54% of Healthcare Global Enterprises (HCG) for ₹3,465 crore, with an open offer for an additional 26% stake worth ₹1,600 crore. The deal follows KKR’s ₹9,400 crore exit from Max Healthcare in 2022 and its estimated ₹2,500 crore buy-in at Baby Memorial Hospital in 2024. HCG posted ₹558 crore in Q3 FY25 revenue and ₹7 crore in net profit. India's cancer incidence stands at 100.4 cases per 100,000 people, projected to rise by 12.8% by 2025.

State-owned NTPC and EDF India have signed a non-binding term sheet to jointly develop pumped hydro storage and hydro projects bundled with renewable energy. The proposed 50:50 joint venture company (JVC) will require government approval and may create subsidiaries for projects in India and neighboring countries. NTPC, India's largest integrated power utility, contributes 25% of the country’s power needs with an installed capacity of over 77 GW. EDF India is a subsidiary of the French multinational Électricité de France SA, which is state-owned by the French government.

Hazoor Multi Projects Ltd (HMPL) has secured a ₹102 crore order to execute steel works in Maharashtra, awarded by Venkatesh Infra Projects. The contract covers reinforcement steel cutting, bending, and fixing as per technical drawings, alongside the fabrication of structural steel for the bridge construction at the Versova Bandra Sea Link project in Mumbai. Scheduled for completion within six months. Moreover, the company is set to expand its portfolio with a planned 500 MW solar project in Andhra Pradesh, involving an investment of ₹2,500 crore.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉