To build factories, build homes

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

“Make in India” needs a place to sleep

Behind the scenes of your 10-minute delivery

“Make in India” needs a place to sleep

Last week, we covered the many trials and tribulations of Foxconn in India.

Mountains were moved to smoothen their entry into India: from land grants, to legal waivers, to geopolitical maneuvering. But there’s one aspect we haven't touched yet. Foxconn was only able to set up base because thousands of workers migrated to where its operations were.

But how do you house so many migrants? To give the 18,000 workers in Sriperumbudur a roof over their head, Foxconn spent $230 million setting up giant dormitories.

This is just one such project. As India tries to build out its industry, we need many more such projects all over the country — lining every industrial cluster in the country. Without that, our “Make in India” dreams will never translate into reality, no matter what other incentives we bring to the table.

A report by NITI Aayog echoed this need for worker housing, and India’s shortfall in that aspect. That’s what we’re looking at to answer one question: what’s stopping us from building more worker housing? The answer, it turns out, is deeply complex — lying in how Indian real estate is organized, the regulations that hinder construction, and ultimately, money.

How worker housing evolved

Many of the world’s biggest manufacturing powerhouses built entire towns for their workers to get by.

Ever come across the chocolate Bournville on supermarket shelves? Bournville was originally a village founded by the Cadbury family. Shoemaker Bata, similarly, was a big proponent of townships. It exported this model wherever it set up shop — including Batanagar in West Bengal.

But the idea really picked up in East Asia. Over the latter half of the 20th century, countries like Taiwan and China began designing their housing around industry.

There, too, Foxconn was at the centre of this push. When Foxconn entered China, worker housing was an important anchor for their manufacturing ambitions. They needed thousands of workers from rural areas, and to attract them, company housing was included in their employment contracts. Together with local governments, the company set up entire townships for people that left their villages to assemble phones for Foxconn. One of them is even called the “iPhone City”. These townships don’t just have houses; they’re filled with amenities — malls, restaurants, hospitals — for workers to access.

Now, don’t get us wrong: townships aren’t always worker-friendly. They often came with heavy surveillance, with serious restrictions on how people live. Foxconn workers, for instance, have often endured restrictions on their movement and cramped living conditions.

Equally, however, such housing was an important ingredient in their manufacturing success.

Why India struggles with townships

In the years after independence, public sector firms like SAIL and NALCO led the charge on India’s economic development. Industrial townships were an official part of their policy. As socialist India pushed for capacity in steel production, entire towns like Bokaro, Rourkela and Durgapur came up around them. Those cities were built almost entirely with “captive housing” to serve those industries.

But over the years, this became a PSU-only phenomenon. Private firms were restricted in their ability to build similar townships. This asymmetry, as NITI Aayog indicates, continued even after the market reforms of 1991. Worker housing was simply not prioritized alongside the expansion of industry.

A lot of India’s factory workers live in unauthorised housing. These aren’t built by formal developers, but by standalone landlords and labor contractors. There’s little government oversight, and building standards are rarely followed. These are, however, the only options workers find close to their workplace — often the most important criterion for them. There’s simply very little choice.

For instance, take Delhi’s garment cluster — covered by the Foundation for Economic Development (FED). It has informal colonies with tens of rooms for its workers. Each of these costs a garment worker ₹3,000 a month — half their salary, but still cheaper than formal housing. Multiple workers usually share a single room, and there’s usually a single bathroom to cover multiple rooms. These colonies also have poor access to basic utilities like water or electricity.

Why isn’t there something better for them?

For one, there’s little incentive for these informal players to improve these settlements. Workers hardly have the ability to pay a premium for good housing, and besides, they usually treat their current situation as temporary.

But that’s only part of the problem.

Real estate, in India, is terribly fragmented. India’s housing stock simply hasn’t kept up with how quickly we are urbanizing. Our cities face a shortage of more than 30 million homes in cities. People with low incomes — factory workers included — naturally find it the hardest to afford one.

For good worker housing, you need coordination between the government, private manufacturing companies, and property developers. India has very little on offer.

Just take the dual-model Affordable Rental Housing Complex (ARHC) scheme — a massive government scheme meant to give migrant and low‑income workers dorm‑style homes close to their job sites. The Centre offered two tracks: Model 1 turns thousands of long‑vacant JNNURM/RAY flats into hostels, while Model 2 lets private or public entities build brand‑new blocks on their own land and run them for 25 years.

Tragically, neither track took off. Merely 7% of the proposed complexes under Model 1 were converted into ARHC units. The government only managed a total of ~35,000 beds across India under Model 2. Worse still, not all of these houses are located anywhere near industrial clusters!

The private sector has no real reason to target the sector either. It’s simply too complicated and expensive to build houses in India. As per KPMG, for instance, more than 80% of all construction projects in India experience cost overruns, while nearly half are delayed. Low-cost housing projects simply don’t justify the risk. And so, private developers largely lean on premium properties instead.

At the root of these problems is how housing is regulated by the government, and how these regulations make financing unviable.

The laws of housing

A major hindrance in building worker housing in India comes from how the government categorises land.

In India, land is often zoned for specific uses — like residential, commercial or industrial. These differ in the areas, laws, standards and even rents.

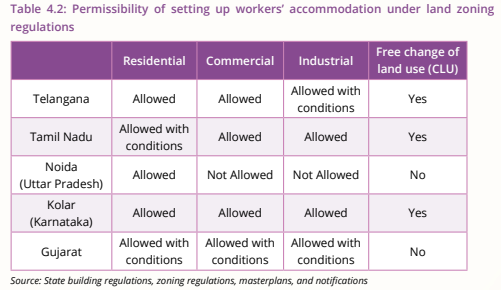

What does worker housing fall under? Well, that isn’t entirely clear.

Different states have very different answers to that question. In Noida, it is forbidden to use an industrial plot for new worker housing. In Tamilnadu, hostels — often run by unorganized players — are considered “commercial”, except if they are hostels meant only for working women. In Kolar in Karnataka, worker housing can be built anywhere. There’s simply no consensus.

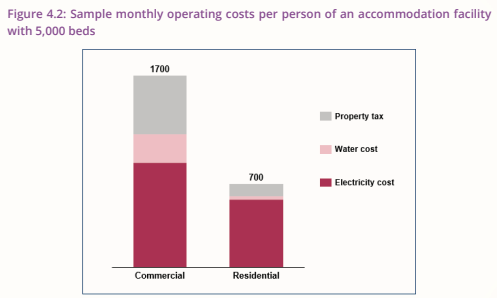

These have serious financial implications. For instance, if you’re building on residential land, you pay a fraction of the rent or utility charges people pay for commercial land.

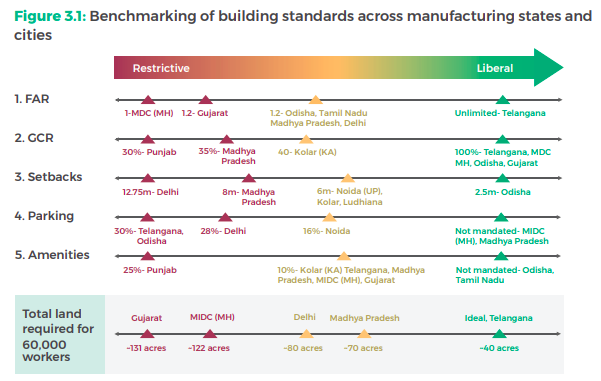

Add to this our building standards, which are routinely very restrictive. For instance, many states restrict the Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which determines how tall a building can be. That means that you can’t build tall buildings which house a lot of workers; you must mandatorily buy more land for them. Similarly, such projects often come with mandatory parking requirements, even if they’re for low income workers.

These standards often lead to delays. The entire process of approval can take as long as 2 years.

To anyone building housing, all these restrictions become financial issues. It’s hard to get financing for such projects too, and there have been few structural efforts to make credit cheaper for developers. Meanwhile, these properties yield low returns. As per the Global Property Guide, India’s rental yields at 2.3% are among the lowest in Asia.

With all these problems, building any housing can turn into a nightmare. Low-cost housing for factory workers? It simply makes no sense.

What models have worked?

Through all this, are there solutions that have actually worked?

One thing is clear: successful projects involve not just coordination between private and public entities, but also clarity in the roles of central and state governments. The NITI Aayog names several such examples:

Foxconn’s $230 million housing project.

The Tiruppur garment cluster, where a PPP was created to build a township for workers who lived in informal settlements.

Gujarat’s hostel in the Sanand industrial cluster, built through a PPP led by the Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation.

All of these models involve some level of public-private partnership.

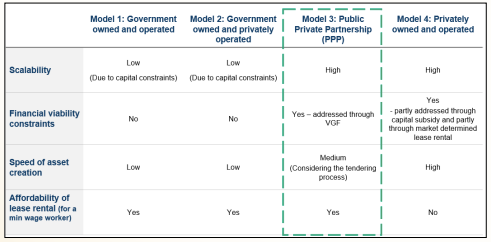

But the NITI Aayog also points to a challenge: if you want the private sector to step in, it’s important to think hard about the financials, especially since a lot of this housing would be for low-income workers. Who bears the risks of construction and maintenance? How much of the rents are determined by the market versus the state? These projects cannot be purely profit-motivated — but they must still make financial sense.

This matrix below by NITI Aayog lays down the possibilities of where that sweet spot might lie: where the government gives out tenders, and financial support to get over constraints.

Another solution is to use CSR funds to build industrial housing, much like how industrial houses like Tata did. Earlier this year, Mumbai-based real estate developer Rustomjee Group used its CSR funds to develop a housing facility covering 35,000 square-feet for its workers.

These continue to be isolated wins, however, often achieved by creating exceptions in laws which obstruct success to occur at scale.

Housing is a problem we must solve

If India is serious about “Make in India,” we cannot treat housing as an after‑thought.

We often claim that our cheap labour is an advantage. But for that to be true, we need to tend to the basic needs of that workforce. Every new factory that breaks ground will necessarily draw a fresh wave of migrant labour; and every such wave needs somewhere safe, dignified, and affordable to sleep.

As long as our land‑use rules remain fuzzy, approvals slow, and the basic math doesn’t work for private builders, those workers will keep squeezing into unregulated dorms — or worse still, simply stay away.

The next Foxconn‑style mega‑plant will test whether we have learned the lesson. If a worker can step off a bus and find a clean room within walking distance of the shop‑floor, India’s industrial ambitions will have a solid foundation. If not, we might keep moving mountains for marquee investors, but the people to power their investments will simply never show up.

Behind the scenes of your 10-minute delivery

We haven’t spoken about quick commerce for quite some time, here. But recently, we came across some interesting news: Blinkit is now shifting to an inventory-led model from September. For nerds like us who have closely followed this space, this move is particularly fascinating.

But that’s also a very specific change, and understanding it requires a lot of context. It’s also an entry point into a fascinating world.

Imagine you open a quick commerce app, and place an order for tomatoes and a nail cutter. How in the world does it come to your doorstep in 10 minutes? There are a lot of non-obvious, almost invisible operations that work in tandem to ensure your delivery reaches you in the time it takes to take a shower.

Curious about what they are? Let’s dive in.

The rise of quick commerce

It’s easy to forget just how new this all is. Just four years ago, the idea of a 10-minute delivery was almost inconceivable. When it was first introduced, the common response was: “Why would anyone need fruits delivered in 10 minutes?”

Oh well.

Fast forward to today: that initial skepticism has flipped into dependence. It’s now hard to imagine life without it. The sheer scale it has reached is mind-boggling: the total Gross Merchandise Value (GMV), essentially the value of goods sold on quick commerce platforms, has surged to roughly ₹64,000 crores in 2025.

Why has this model, one that has struggled in most global markets, found such fertile ground in India?

There may be many reasons for this. One, of course, is India’s relatively lower labor costs. But that’s only a complementary factor. Labor costs can make such an operation viable, but they don’t explain the blistering pace of adoption.

When we spoke to people across the quick commerce ecosystem, one thing popped up over and over again: the Indian customer’s psyche.

In the US, for instance, grocery shopping tends to be bulk-oriented and focused on shelf-stable goods. In contrast, Indian consumers follow a more 'top-up' approach — we shop out of need, not habit. Rather than stockpiling supplies for weeks, we frequently buy just what we need: milk, vegetables, everyday essentials.

This frequent ordering behavior aligns perfectly with quick commerce, which is designed to handle multiple small, frequent orders rather than large bulk orders.

Initially, these platforms were built entirely around these habits. They focused primarily on milk and groceries, sticky product categories that customers would return for regularly. But once consumers got used to the convenience of ordering essentials instantly, the platforms began expanding their catalogs. Quick commerce platforms now practically act like a mall, offering everything from an apple to an air conditioner.

The mechanics of 10 minute delivery

So how does a 10-minute delivery actually happen?

When you place an order — say, four or five items — on your favorite quick commerce app, it sets off a finely tuned sequence of events.

Dark stores

The first critical component is the dark store. While dark stores sit at the heart of most quick commerce operations, the companies themselves neither own nor directly operate them.

A dark store is essentially a small, hyper-local warehouse designed solely for fulfilling online orders. A single dark store typically takes up around 2,500–4,000 sq. ft.. It does not accept walk-in customers — just pickers and packers moving swiftly through narrow aisles stacked high with products.

A dark store typically covers a delivery radius of about 1.5 to 2 kilometers. They are strategically placed within residential or densely populated neighborhoods to minimize delivery distances and costs. That is crucial for the promised quick delivery times.

According to an industry report from JM Financial, setting up each dark store requires an initial investment of around ₹85 lakhs — covering real estate deposits, fixtures, refrigeration equipment, inventory setup, and initial staffing.

Picking your orders

When you place an order, it immediately appears on a picker's handheld device. The device also creates a digital map, showing the most efficient route to collect the items you've ordered.

Pickers are trained to follow this digital map. They grab items swiftly, scanning each SKU to confirm accuracy. This picking process is typically completed in around 60-90 seconds, ensuring the products are ready for packing almost instantly.

That speed isn’t just a matter of skill. A dark store is designed for speed and efficiency. Its layout is meticulously optimized to allow pickers to rapidly navigate aisles. Products are arranged logically — fast-moving essentials like dairy, bread, or vegetables are placed near the packing station. Retrieval times for these could be mere seconds per item. Cold storage facilities for perishable goods like milk, dairy, and meats are strategically placed within easy reach.

All this picking and packing happens within a 2-3 minute window. This is ensured through Service Level Agreements (SLAs) between quick commerce companies and dark store operators.

Once picked, your items move to a packing station. Here they're bagged and sealed quickly. The packed order is then placed in a staging area. That’s where it gets to delivery riders. These riders have simultaneously been assigned your order through their rider app, and are already en route or standing by the staging area to collect it. You probably know the rest of the story.

Delivery riders must deliver within the promised 10 minute window to maintain service reliability and customer satisfaction. That is why, within minutes, your tomatoes and nail cutter arrive at your doorstep.

How does something reach the dark store?

Blinkit, Zepto and the likes use detailed analytics and historical purchasing data to decide which products to stock in a dark store. Many factors go into these decisions: local consumption patterns, frequency of purchase, seasonality, profitability, and more.

Typically, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) such as groceries, dairy, snacks, and beverages form the bulk of products ordered and stocked. But that’s not all; high-margin products such as personal care items, household essentials, and packaged foods are also prominently featured to improve overall store margins.

Of course, as orders pour in, this stock keeps running out. And so, the inventory in a dark store is replenished multiple times per day — usually two to three times daily. It gets there from large 'mother warehouses.'

This constant replenishment ensures high availability and minimal stock-outs. Stock levels are monitored continuously through real-time inventory management software, allowing predictive replenishment — that is, when a particular SKU (stock-keeping unit) is running low, the system automatically triggers an alert for replenishment. This ensures that new supplies come in before the store runs out.

Who owns all that stuff?

Historically, quick commerce platforms have largely operated on a marketplace model. Third-party vendors owned and operated dark stores, while companies like Blinkit operated as a “market”, connecting them to customers. Of course, they also provided technology, logistics support, and managed larger mother warehouses. But the dark stores themselves — the heart of their operations — sat in the hands of others. And it was they who owned the goods you would order.

But Blinkit is now moving to an inventory-led model. The company will now directly own and control inventory within the dark stores.

That comes with trade-offs. But interesting, those aren’t as severe as one would imagine.

Ordinarily, you would think that this would be extremely expensive, and would require them to commit a lot of working capital. But interestingly, Blinkit noted in its Q4FY25 shareholders' letter that moving fully inventory-led could result in less working capital requirements than initially expected — less than ₹1,000 crore for FY25.

How come? This reduced capital requirement, it seems, comes from just how quickly products change hands in quick commerce.

In traditional retail, inventories sit on shelves for a long time. And as long as nobody buys it, that cash remains tied up — often for an extended period. Quick commerce, on the other handg operates differently. They stock fewer items and replenish frequently. Inventory is sold and replaced rapidly: what they call “high inventory turnover”.

The faster inventory moves, the less capital is tied up at any one time.

Meanwhile, direct inventory ownership may help Blinkit to negotiate better terms with suppliers and secure higher margins. Think about it: if Blinkit buys Maggi, say, for all its operations across India, how much cheaper could they get it? Meanwhile, they also maintain product quality, reduce stock-outs, and maybe even improve overall customer experience. All of this could turn into more profits, and greater competitive advantage.

Bottom line

Behind the promise of a 10-minute delivery is a carefully built system that most of us never really see. There are small warehouses tucked into neighborhoods, pickers moving fast through narrow aisles and a constant race against time. All so we can get a packet of milk or a bar of chocolate without stepping out.

It feels seamless on the surface, almost magical. But the truth is, there’s nothing effortless about it. Every bit of that convenience is carefully designed, planned, and executed. Quick commerce may feel invisible, but it’s one of the most visible examples of how deeply technology, logistics, and human effort can come together to shape the way we live.

Tidbits

We flagged the building pressure in India’s IT sector due to Trump's tariff plans, and tightening client budgets. That pressure seems to be translating into pain.

And the cracks are no longer limited to clients or contracts. TCS is facing heat from inside the house. A top IT workers’ group has written to the Labour Ministry accusing the company of coercive practices under its new “bench policy.” Employees without projects for more than 35 days in a year reportedly risk career stagnation — or worse, termination. The union claims the policy fosters “a culture of fear,” especially for workers stuck in allocation limbo due to shifting business priorities.

Source: Business StandardGold is something our country (and the rest of the world) cannot escape. We have covered the relentless rise of gold prices before.

And now, India's markets regulator, SEBI, has proposed requiring asset managers to use domestic spot prices for valuing gold and silver in mutual funds and ETFs. This move aims to enhance transparency and standardize valuation practices, especially as gold ETFs saw a tenfold surge in inflows last month amid global economic uncertainties.

Source: ReutersWe’ve explored how India’s leading hotel chains are placing long-term bets. ITC Hotels has just checked in with numbers that reinforce the same story.

The newly demerged hospitality arm of ITC reported a 54% YoY surge in Q1 FY26 net profit, touching ₹133 crore. Revenue rose 15% to ₹815 crore, even as May’s geopolitical jitters — which hurt other hotel chains — briefly disrupted business. ITC Hotels has now crossed the 200-property mark, with 13,400+ keys and a strong presence in both metro and spiritual destinations.

Source: Business StandardCinépolis India is targeting double-digit revenue growth in 2025 by expanding its screen count and capitalizing on a strong lineup of Hollywood and Bollywood blockbusters. The company plans to add 20 to 25 new screens to its existing 485, aiming to boost admissions that are currently 20% below pre-COVID levels.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Krishna.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Super insightful, even as a reader based in Malaysia. The deep dive into Indian worker housing was especially striking.

Housing really is a complex issue across many developing countries. Coming from logistics, the teardown on quick commerce and the BTS of 10-minute delivery was a fun and familiar bonus.