There isn’t enough copper in the world

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

There isn’t enough copper

How India divides its money

Before we start, a quick note from us.

We’ve spent a lot of time at The Daily Brief writing about the less-visible parts of electronics — semiconductors, PCBs, and everything around them.

We recently released a podcast with someone who’s spent years actually making PCBs, talking through how they work, why they matter, and where India still struggles. If you’re curious, you can listen to the conversation here on YouTube.

If you prefer to listen to the audio, you can check it out on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. Now, back to The Daily Brief.

There isn’t enough copper

Today, we might see the birth of the largest mining company in history.

Rio Tinto and Glencore — two of the world’s biggest miners — have been in talks since early January. If they combine, the resulting company would be worth more than $200 billion. More importantly, it would control a staggering share of global copper production at a time when every country on Earth is desperate for more of the metal.

In a previous edition of The Daily Brief, we looked at the copper value chain: how copper moves from ore in the ground to cathodes on the market, why India is a net importer despite having smelting capacity, and why the economics of this business are so brutal. If you haven’t read it yet, we would urge you to do so to get a better understanding.

This piece is about what’s happening one level up. The mining giants are circling each other, governments are building strategic stockpiles, and everyone is trying to lock up supply before someone else does.

Let’s start by understanding why.

The supply crunch

The easy copper has already been mined. Decades ago, the best mines operated at ore grades of 1.5% or higher — 1.5 kg of copper for every 100 kg of rock. Today, many mines operate below 0.6%. You have to dig up more than twice as much rock to get the same copper.

The geography doesn’t help, either. Chile produces nearly a quarter of the world’s copper, but most of its mines sit in the Atacama Desert — one of the driest places on Earth.

Copper processing is extremely water-intensive. You need water to separate copper from rock, to suppress dust, and to cool equipment. As mines have expanded and droughts have worsened, there simply isn’t enough water. Some mines have cut production. Others are spending billions to build desalination plants on the coast and pump seawater hundreds of kilometres into the mountains.

But in the past two years, things have gotten dramatically worse. Two of the world’s most important copper operations have gone offline.

Cobre Panamá was one of the largest new copper mines to come online in the past decade.

Run by Canada’s First Quantum Minerals, it cost $10 billion to build — the largest private investment in Panama’s history. At its peak, it produced around 3.5 lakh tonnes of copper per year — ~1.5% of global supply. In late 2023, Panama’s government tried to renew the mine’s operating contract. But when the terms were announced, it sparked massive protests.

Panamanians blocked roads for weeks, arguing the deal favoured the mining company and the environmental damage wasn’t worth it. Then, in November 2023, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled the contract unconstitutional, and the state ordered the mine shut. It has remained closed ever since, and all that copper just sits there.

Then, there’s Grasberg in Indonesia, the world’s second-largest copper mine. On September 8 last year, it was struck by a massive disaster that resulted in the mine being closed down.

Grasberg used to be an open-pit mine — basically a giant hole in the ground. Over decades, they dug out the richest parts and eventually transitioned to underground mining, tunneling beneath the old pit. However, the old pit was filled with water and unstable material. When conditions shifted, 8 lakh tonnes of waterlogged mud surged into the underground operations. Seven workers died, and the entire complex was shut down. Freeport-McMoRan, the mine operator, doesn’t expect normal production until 2027.

Add these up: close to a million tonnes of annual copper production — roughly 4% of global supply is just gone.

You might want to ask: why not just build new mines?

The short answer is it takes forever. According to S&P Global, the average time from discovering a copper deposit to producing the first tonne is now around 18 years globally. In the United States, it’s closer to 29 years.

First, you have to find the deposit and drill extensively to understand its size and economics. Then come years of feasibility studies. Then, there’s permitting — environmental assessments, water rights, land access, approvals from multiple agencies. In the US, permitting alone can take 7-10 years. And even after you get permits, you can get sued — environmental groups, local governments, anyone can challenge a project in court.

Consider Resolution Copper in Arizona — one of the largest undeveloped copper deposits in North America. Rio Tinto and BHP have been trying to develop it for over two decades. They’ve spent $2 billion. Due to legal challenges, environmental reviews, and political battles, not a single gram has been mined.

This is increasingly the norm, despite big deposits existing. Getting from discovery to production is so slow and risky that many projects never get built.

The merger wave

So if you want more copper, you have two options. Develop new mines and wait 20 years. Or buy a company that already has producing mines. And option two is increasingly more attractive.

The current wave of acquisitions started in April 2024, when BHP — the world’s largest miner — made an unsolicited offer for Anglo American. BHP wanted Anglo’s crown jewels: Collahuasi in Chile (the third-largest copper mine in the world) and Quellaveco in Peru. These are exactly the long-life, high-quality assets that everyone wants but nobody can build anymore.

Anglo’s board rejected the offer. The real problem was BHP’s structure — BHP didn’t want all of Anglo American, it wanted the copper. So BHP proposed that Anglo first spin off its South African platinum business and its iron ore business into separate companies. Only then would BHP acquire what remained.

Think about what this means for Anglo’s shareholders. They’d have to execute two complex corporate spin-offs — each requiring regulatory approvals, tax structuring, and market timing — while simultaneously negotiating a takeover. If copper prices dropped during the process, or regulators delayed a spin-off, or markets turned, Anglo’s shareholders would bear the losses while BHP walked away unscathed. Anglo said no. BHP came back with revised offers but kept the same structure.

Eventually, BHP walked away.

But Anglo didn’t stay independent. In September 2025, it announced a merger with Teck Resources, a Canadian miner. This deal made operational sense in a way BHP’s didn’t. Anglo’s Collahuasi mine and Teck’s Quebrada Blanca are just 15 kilometres apart in Chile’s Atacama Desert. Right now, each mine has its own processing facilities. By combining and sharing facilities and resources, they expect to unlock 1.75 lakh tonnes of extra copper production annually, and more efficiently.

And now Rio Tinto is trying with Glencore. This isn’t their first attempt. Glencore approached Rio Tinto in late 2024 about a potential merger, but the talks went nowhere. The two sides couldn’t agree on valuation.

And then, there was the coal problem. Glencore is one of the world’s largest coal producers. Rio Tinto, on the other hand, exited coal back in 2018 after years of pressure from ESG-focused investors. Taking on Glencore’s coal business would mean reversing that decision and facing shareholder backlash.

So what changed? For one, Rio Tinto got a new CEO in August 2025, who is seen as more open to large deals than his predecessor. Copper prices have also surged to record highs, making Glencore’s copper assets even more valuable. And perhaps most importantly, the Anglo-Teck merger proved that mega-deals in mining can actually get done. It looks like that gave both sides confidence to try again.

For Rio, acquiring Glencore means not just more mines, but control over more of the supply chain. That’s because unlike most other miners, Glencore is also one of the world’s largest commodity traders. It buys metals from third parties, moves them globally, and has relationships with customers that no other miner can match.

The sticking points remain valuation and coal. Today’s deadline might get extended. But the logic is clear: when copper is this scarce, owning more mines is a strategic imperative.

The geopolitical layer

It’s not just mining companies scrambling. Governments are getting involved.

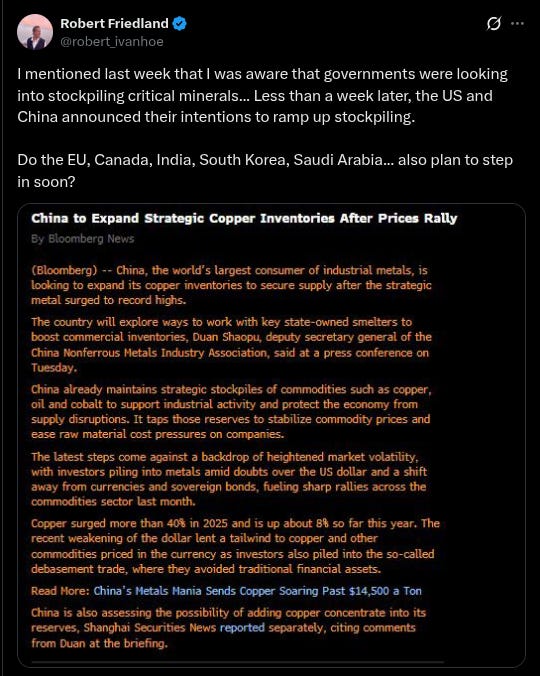

China has been stockpiling critical minerals for years. Just 2 days ago, a metal association in China called for the government to stockpile copper. China cares so much because it consumes half the world’s copper and processes 57% of the global refined supply.

If concentrate shipments get disrupted, Chinese smelters go idle. If refined copper gets disrupted, Chinese manufacturing suffers, so sockpiling is insurance.

The US is trying to catch up. Two days ago, President Trump announced “Project Vault” — a $12 billion initiative to build a strategic minerals stockpile. Think of it like the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, but for metals. The US has long maintained emergency oil reserves in case of supply disruptions. Now it’s trying to do the same for copper, rare earths, and lithium.

And the US is buying into mines directly. Yesterday, Glencore announced it was selling a 40% stake in its DRC copper and cobalt mines to a US-backed consortium. The deal values those mines at $9 billion. The US consortium gets to direct where its share of production goes. Not to whoever pays the highest price, to wherever the US wants.

The picture emerging

The world needs vastly more copper than it produces. EVs use four times as much copper as conventional cars. Solar, wind, grids, data centres — all copper-intensive. Demand is growing.

Supply is constrained, and ore grades are falling. In this environment, copper has become strategic, like oil in the 20th century. Countries are stockpiling. Governments are investing in mines. Companies are merging to control what’s left.

Today, Rio Tinto decides. But whatever happens, the scramble for copper is just getting started.

How India divides its money

From the very birth of our nation, the Indian Constitution created an imbalance.

It assigned states the responsibility for most things that matter to citizens’ daily lives — health, education, law and order, agriculture, and the like. But it was the central government that got the most lucrative tax handles: income tax, corporate tax, customs duties, and the like. States were left with fewer avenues to raise money, each of which would yield less: land revenue, stamp duties, excise on alcohol, and the like. The two levels shared indirect taxes in a massive hodge-podge.

This asymmetry was intentional. It had been inherited from the British-era law, the Government of India Act, 1935, which kept taxing power at the centre while pushing spending obligations to the provinces. The centre, it was believed, was just a more efficient revenue-raising body. But there was something else too — in those early days, when there was a palpable fear that India would not survive as a political unit, it made sense for the centre to hold the country’s funds.

But this design created an obvious problem: without those revenues, how would states fund their many responsibilities?

The constitution filled that gap with transfers. The centre wouldn’t just collect tax for itself; it would collect tax for the states as well, and send that money to them.

This created another question: how would we know which state was owed what sum? To answer this, the constitution set up a Finance Commission, which would be appointed every five years. This commission would decide on how much of the centre’s revenues should go to states, and how much different states would get.

The recommendations of the latest of these — the Sixteenth Finance Commission, chaired by noted economist Arvind Panagariya — were just accepted by the government. You may have heard a mention of this in the recent budget speech as well. There’s a complex thought process behind that single line, which we’re going to dive into below.

The questions before the Finance Commission

A government body created to determine tax shares might well sound like the most boring thing there is. We assure you, it is not. This single body decides the fate of where more than ₹20 lakh crore will go every year — more than 6% of India’s entire GDP. For many states, such transfers make up nearly half the money they have.

So, how does it go about answering such a mammoth question?

You can think of the Commission as having two different functions. The first is vertical devolution: or, figuring out how much of the centre’s tax collections ought to go to the states. The second is horizontal devolution: or figuring out how that kitty gets divided among India’s 28 states. Each exercise has its own logic, its own tensions, and its own politics.

What gets shared

Under the constitution, the centre is supposed to give states a share of all the taxes and duties it collects. But there’s a loophole: the central government can also place extra charges on you: called cesses and surcharges. To a payer, these behave just like taxes. But they’re outside the realm of what the centre has to share.

This loophole is one of the most important, albeit under-appreciated, controversies in Indian politics. See, in recent years, the number of cesses have multiplied. If you’ve ever wondered why you’re paying a small “health and education cess” on top of your yearly income tax, for instance, this is why.

Each such cess or surcharge lets the centre keep a little more revenue with itself. When we’re calculating the pool of central funds that states have a right over, we carve those amounts out, and only then come up with what’s called the “divisible pool‘. This divisible pool has been shrinking. Between 2010 and 2015, the pool made up around 89% of the centre’s tax revenues. Over the last five years, that has declined to ~78%.

States have complained bitterly about this trend, and how it limits them to a shrinking pie. Changing this, however, is outside the Finance Commission’s powers. It is simply how the constitution is designed.

It did, however, set the terms for the clash ahead.

See, in theory, the Commission is trying to balance three estimates: what the central government can reasonably collect, what its spending needs are, and how much money states need beyond what they can raise. This is a mathematical exercise, on paper, where the Commission keeps tweaking its assumptions until it finds a formula that works.

Of course, in reality, these splits are hotly contested, with continuous negotiation and lobbying.

The process threw up the same number the last Finance Commission had landed on: 41%. The shrinking “divisible pool” was central to its decision. On one hand, the Commission argued that if so much of the centre’s finances came in through cesses and surcharges, there was simply no room for the state’s share in taxes to go any lower. On the other hand, it pointed out that if the share of states were to increase, that would only accelerate the centre’s flight to cesses and surcharges. Ultimately, it stuck to status quo.

It did, however, propose a “grand bargain”: if the Centre agreed to fold a substantial portion of its cesses and surcharges into regular taxes, states could accept a smaller percentage of the resulting larger pool. This would leave them with similar revenues, but with a healthier structure. But this is a mere suggestion; the Finance Commission doesn’t actually have the power to broker such a compromise.

How sharing happens

This isn’t just a question of what the states collectively get, though; but also what each of them receives individually. States are competing with each other, here — if another state gets more, yours may get less.

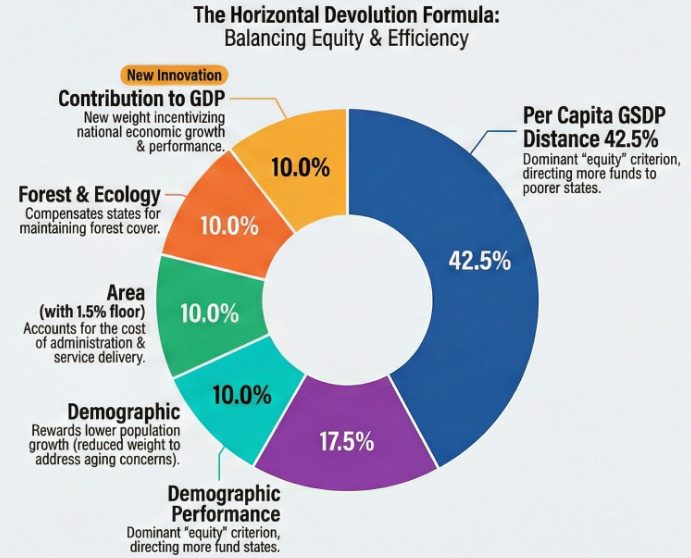

How should their shares be decided? Well, ultimately, the Commission comes up with a formula, where it gives different weights to a variety of criteria. This time’s criteria look like this:

Behind this, though, is an almost philosophical question, based on how you think of two competing objectives: equity and efficiency.

Collecting tax money is easier in some states than others. A state with a larger, more formal economy — say, like Maharashtra — would find it easier to draw revenue than a poor state — like Bihar. This could keep poor states trapped in a loop; where they consistently provide inferior public services, which keeps their economies perennially underdeveloped. The equitable response, then, would be to compensate for these differences, directing more resources into poorer states, or those that find it harder to deliver services.

But there’s another way of looking at it. Ideally, you want to incentivise states to perform better. If states know that their revenue shortfall will be covered by transfers, they have little reason to collect taxes diligently, or spend carefully. If you’re seeking efficiency, you want to reward states that manage their finances well, promoting better behaviour across the system.

Which is better: equity or efficiency? Should we penalise states for their success? Or should we abandon any hope of balanced development? Every Finance Commission must choose how to answer this question.

Ever since the late 1970s, most Commissions have pushed strongly for equity. The biggest weightage, in these transfers, almost always goes to a state’s “distance” from national income levels. This time around, as well, the “distance” of a state’s per-capita GDP from the national average has a weightage of 42.5%.

But that said, the Sixteenth Commission takes small steps towards efficiency. The distance criteria, for one, has come down to 42.5% from 45%. It has also introduced a new criteria — “contribution to GDP” — which has a 10% weightage. That’s a first; where the Commission is explicitly rewarding states for their economic heft. In its reasoning, the Commission explicitly notes that if it aspires to become the world’s third largest economy, it cannot penalise the states driving its growth.

Winners and losers

To be fair, these changes are more dramatic than they seem. The Commission has overwhelmingly embraced gradualism. Even criteria like “contribution to GDP” are calculated in a manner that diminishes their impact.

That means the newest commission retains some of the asymmetries of the older ones. North India’s most populous states — Uttar Pradesh and Bihar — still lead the allocations. Per person, meanwhile, northeastern and hilly states receive shares that are dramatically higher than others. Arunachal Pradesh, for instance, receives nearly fifteen times the national per capita average. Sikkim receives about eight times as much.

That said, in relative terms, India’s most developed states have gained the most from this Commission’s findings. Karnataka’s share, for instance, has jumped up by 0.48%. States like Kerala, Maharashtra and Gujarat, too, have seen a bump. Meanwhile, states that have historically received dominant shares because of their demographics now face modest losses. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, for example, have both seen their allocations fall.

No grants for deficits!

These splits are not all that the Finance Commission decides. It also looks at the grants the centre gives states outside this revenue-sharing formula. And that is perhaps where its most consequential decision lies.

For decades, the central government would give states “revenue deficit grants” where their expenditure needs exceeded the money they received. This was practically a feature of every previous Finance Commission. In theory, this would give states some breathing room in which to resolve their finances. In practice, however, it became a moral hazard. States began anticipating that their deficits would be filled, and did little to reduce their deficits.

The 16th Finance Commission, now, recommends zero revenue deficit grants for the award period.

Yesterday, we talked about how states had been announcing massive cash transfers and subsidies, often at the cost of other public services. The Finance Commission, too, took note of this trend. Unconditional cash transfers alone, for instance, have surged from ₹3,000 crore to over ₹4 lakh crore since FY 2019. With such wanton expenditure, the Commission refused to give credibility to states’ contentions that they were cash-strapped.

States have a duty to be sensible

The Commission’s recommendations send a broad message: fiscal discipline is the responsibility of states.

It doesn’t abandon equity. Poorer, more remote states continue to get a higher share than their populations would suggest. The way India is organised, some states must carry the weight of growth, while others are nudged along as they try to catch up. Even in its sixteenth round, the Commission maintains this wider compact.

But it does nudge the system towards better performance, at least compared to its predecessors. It rewards economic success, and withholds deficit grants. In that sense, it signals that a states’ profligacy will no longer be underwritten by the others.

Tidbits

Alphabet ramps up India hiring, expands Bengaluru footprint

Alphabet has leased a large office tower in Bengaluru and may take up two more buildings, potentially doubling its India workforce. The expansion could house up to 20,000 employees as the company shifts more work to India. Tighter US visa rules are accelerating this move.

Source: ReutersBYD plans India-focused electric vehicle

China’s BYD plans to launch an electric vehicle designed specifically for Indian buyers. The move is part of its global expansion strategy as competition in India’s EV market intensifies. Local preferences and pricing are likely to be key to BYD’s success.

Source: ET AutoMusk merges SpaceX and xAI to bet on space-based AI

Elon Musk has merged SpaceX and xAI to build AI data centres in space. He argues that AI’s power needs are becoming unsustainable on Earth and space offers limitless solar energy. The plan aims to make space-based computing viable within a few years.

Source: Al Jazeera

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉