India’s biggest challenges, according to the Economic Survey

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s biggest challenges, according to the Economic Survey

Distilling the results of Indian alcobev

India’s biggest challenges, according to the Economic Survey

Today, we’re going to look at the Economic Survey that was released just before the budget.

This is, naturally, a mammoth document, with its hundreds of pages examining every nook and cranny of the Indian economy. There is no way we can do justice to it all. So, for our story, we’re going to limit ourselves to what, in our opinion, are the five biggest challenges it believes our economy is currently facing. That isn’t to suggest that the survey only highlights challenges — it lists plenty of successes as well. But that said, the challenges are pressing. At a time where the global economy looks so uncertain, it is worth knowing where we can improve, ourselves.

We do recommend, however, that you flip through the entire survey yourself, if you’re interested in knowing how our economy works — as you probably do, if you’re tuned into The Daily Brief.

The world is tearing itself apart

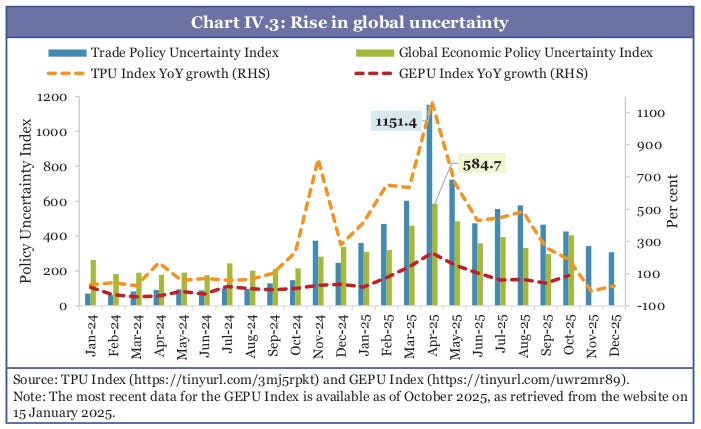

The overwhelming context, for this year’s economic survey, is the deep uncertainty in which India functions. The assumptions which shaped global trade for decades have broken down. As the survey noted, since April 2025, trade policy uncertainty has jumped twelve-fold year-on-year. The broader economic policy uncertainty index — which tracks everything from sanctions to industrial subsidies — rose 228%.

Growth is hard in good times. And now, we have to survive serious instability to develop.

The problem won’t disappear simply because India finally won a trade deal from the United States. There’s a wider shift the survey points to; that countries are increasingly treating trade as an extension of their national security. They’re willing to bear serious economic costs to corner key parts of the world market, from chips to critical minerals.

This brings a cluster of bad news for India.

For one, as recent experience with the United States has shown, export markets have become hard to predict. This isn’t a matter of tariffs alone; without long-term certainty, it is genuinely harder for businesses to form cross-border links.

At the other end, it also creates supply shocks for Indian manufacturers, as they abruptly find themselves shut out of global value chains.

If our exports are hit, that automatically brings currency pressures. India is growing rapidly, which pushes it to import goods at an accelerating pace. When exports suddenly drop, that can rapidly open up a balance of payments deficit. This is perhaps what caused the Rupee to drop 6.5% in value between April 2025 and January 2026. Such a drop, in turn, can push foreign capital out — making it harder to fund the gap.

How do we survive a time like this?

The survey pushes for what it calls “strategic indispensability”; that is, we need for the world to depend on us in key domains, making us a node that is hard to by-pass. To the survey, this is only possible with better manufacturing. The goal isn’t universal self-sufficiency; that is too expensive to sustain. But we need to selectively build depth in areas that matter strategically, to be in a better place for tomorrow’s trade negotiations.

The stress on state finances

Internally, meanwhile, the survey flags serious problems with India’s fiscal management — especially at the states.

India’s central government, the survey believes, is trying to become smarter with how it spends, borrowing less while pursuing more future-oriented capital expenditure. The same cannot be said for India’s states. Not too long ago, during the COVID-19 crisis, Indian states had tightened their fiscal belts. But in the years since, they’ve slipped back into bad habits.

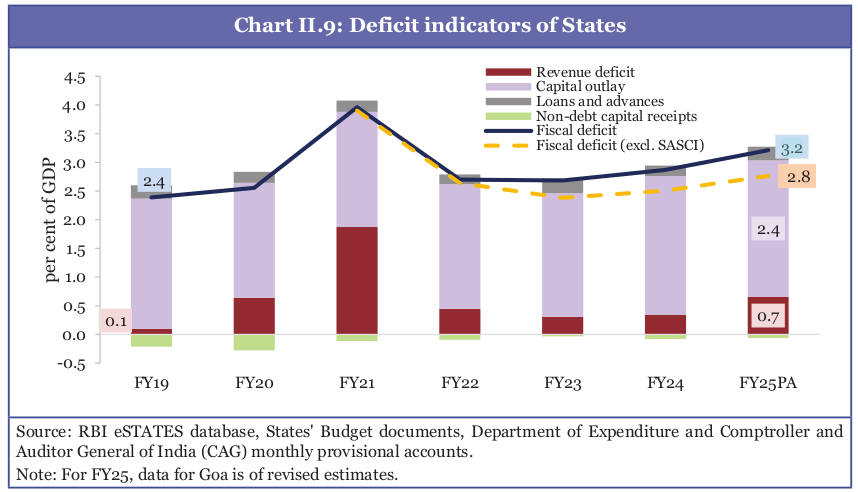

India’s state governments are spending way beyond what they earn, running ever-larger deficits. In FY 2025, their fiscal deficits touched 3.2% of India’s GDP — well higher than they were before the pandemic.

More worryingly, this money isn’t going into building long-term assets, like roads or power plants. Increasingly, states are borrowing to fund their day-to-day expenses. Their revenue deficit alone — that is, the gap between what they earn and what they spend on recurring payments like salaries and subsidies — has grown from 0.4% to 0.7% of GDP since FY 2022.

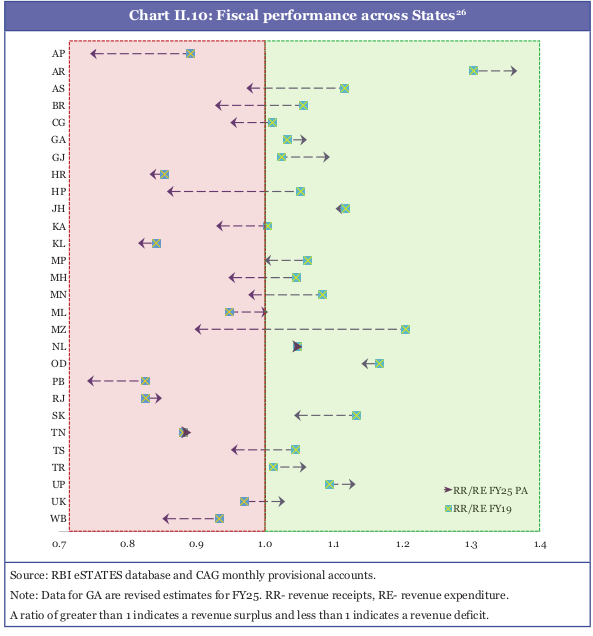

In fact, eighteen Indian states have seen their fiscal performance grow worse in the last six years.

What’s pushing this splurge?

A big culprit, the survey believes, is the trend of states handing large out massive cash doles to people, with no strings attached. Often, these come with no end date, and no mechanism for review — which means that states are effectively locked into these transfers, with no easy way of stopping them.

This leaves them less money to invest in productive things.

The central government is masking this decline — they’re giving states interest-free loans to pursue capital expenditure, which is why investment levels seem flat. Without that, however, states’ own investments have fallen considerably since FY 2022, from 2.11% to 1.92% of GDP.

This, the survey highlights, is partly an incentive failure. Ideally, markets would punish states with weaker finances by forcing them to pay more interest. That hasn’t happened. Most “State Development Loans” are held by domestic institutions, who rarely trade this debt on secondary markets. Because of this, states with very different fiscal profiles end up paying the same for their loans. If anything, our worst performing states are sending up borrowing costs for everyone.

It’s possible that the decisions of the latest Finance Commission could change this. We’ll go into it one of these days.

The competitiveness problem

Perhaps the most persistent problem with India’s economy is its inability to build a serious manufacturing presence. Despite being the world’s fourth largest economy, we account for just 2.9% of the world’s value-added manufacturing, and just 1.8% of its merchandise exports. We rank 44th on the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) — where we’ve been stuck since 2019.

We simply aren’t embedded in global production networks, the way so many of our peer economies are. That creates a variety of problems for us, from persistent a drop in our exchange rate, to our severe inability to employ our massive workforce. Exporting services, the survey argues, simply doesn’t close those gaps.

Where are we falling behind?

The survey is littered with our many problems. Our industries are starved for capital. They pay too much for electricity. Our logistics costs are too high. We lack a good research ecosystem. Regulatory uncertainty keeps us from creating industrial clusters, which prevents us from making the sorts of manufacturing hubs that have been so successful in China and Vietnam. And so on. We’ve spoken about these issues often on The Daily Brief, so we’ll leave it at that.

How do we solve this problem, though?

The survey argues for backward integration. That is, instead of trying to make everything here, we need to import intermediates and components from abroad, assemble them, and slowly climb up value chains. This strategy could seem counterintuitive — it nudges us to import more, and add less value at home. But the survey argues otherwise. It’s only when we use world-class inputs that others would want our finished goods, and that’s what will allow us to produce more.

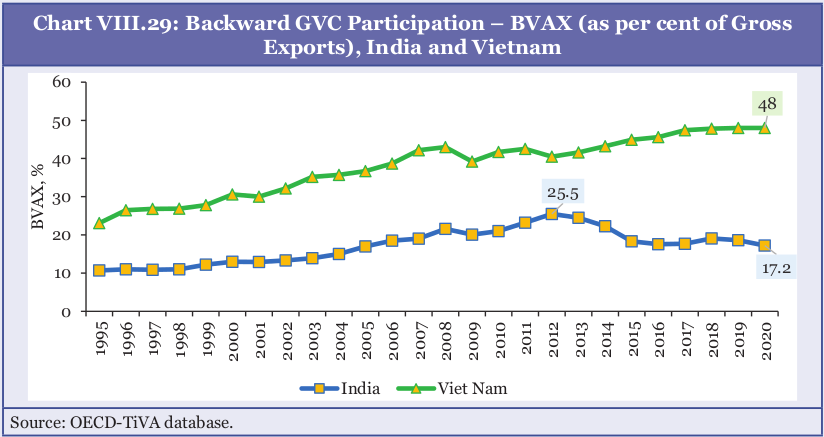

This is what other manufacturing-heavy economies have done. 48% of the value in Vietnam’s exports, for instance, come from abroad. India’s foreign share, meanwhile, is at 17.2%. But that approach has allowed Vietnam’s manufacturing industry to add more total value in their country than we do.

Right now, India’s tariff structure goes against this. We have higher duties on many intermediate products than the finished products that make them — what economists call “inverted duties”. This discourages businesses from setting up assembly hubs here.

Interestingly, this year’s budget goes some way in correcting that inversion.

Capital starvation

Indian businesses are starved for capital. As foreign investment dries up, that problem is worsening.

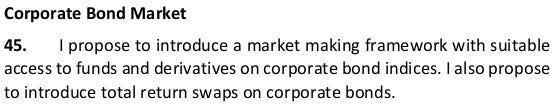

We’ve known, for a long time, that our domestic financial system isn’t deep enough to give Indian entrepreneurs the money they need. Our corporate bond market, for instance, is surprisingly anaemic — making for roughly 15-16% of our economy, compared to 79% in South Korea and 54% in Malaysia. Our secondary bond markets are thin, which means that bonds are generally held to maturity. As a result, nearly 90% of the market is concentrated in AAA and AA-rated paper. Mid-sized firms with lower credit ratings — that is, those that need capital the most — struggle to access bond financing at all.

This year’s budget tries to correct that, somewhat.

But this is just one symptom of a deeper, macroeconomic problem.

As the survey puts it, Indian businesses do a poor job of creating capital. Their productivity is low, which only permits thin margins. They don’t create sizable savings. This, combined with a series of other market distortions, means that India’s economy is unable to generate the financing it needs.

Without financing, India’s businesses are constantly underpowered. For instance, MSMEs account for roughly one-third of India’s manufacturing output and half of its exports. Yet one-fourth of them consider access to finance as their biggest obstacle.

Without enough domestic capital, we’re structurally dependent on foreign capital to fund investment. And they don’t bring money in for free. They demand a risk premium, which pushes up the cost of borrowing across our economy. And at a time like this, when global conditions are weak, they’re likely to pull out of riskier markets like ours and flee for safety.

What can we do to get around this?

For one, we need to fix our financial market plumbing, and ensure that the friction there is limited. We need to deepen bond markets, expand credit access, improve insolvency resolution so that dead capital doesn’t get stuck, and more. But financial flows, alone, won’t fix our problem.

Over the long term, if we want durable, cheap capital, we need a different growth model, which prioritises productivity-led manufacturing. It’s only by bringing in a persistent supply of money by selling to the world that we can durably make capital cheaper. Until then, we’ll be dependent on foreign savings, which will always come with a risk premium.

Can India skill up?

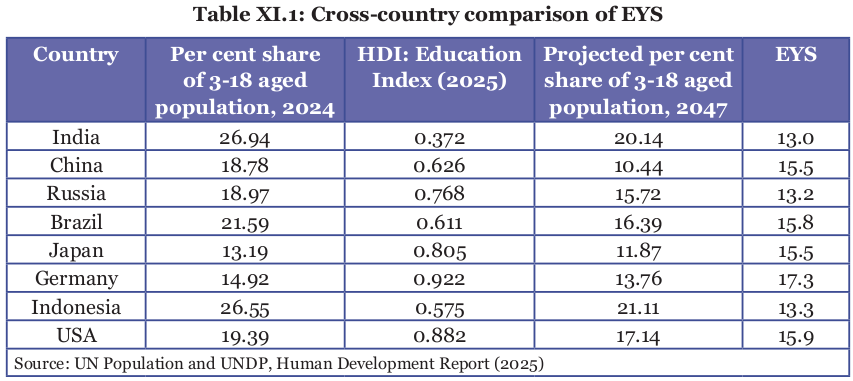

India, by all accounts, should be right in the middle of a demographic dividend. Our working age population is expanding rapidly, at the moment. Ideally, those additional workers should propel our economy much further.

The survey, however, notes that a young population only translates to growth if those people can do work that employers need. Those new workers need to be given the skills to perform new roles in our economy, through a pipeline that runs from the education system to the workplace. Sadly, India lacks that.

For one, our existing pipeline leaks. Net enrolment at the secondary level sits at just 52.2%. That is, nearly half of India’s students drop out of school before they’re adolescents. This is for many reasons, including the fact that a large share of adolescent Indians need to work to support their family. But there’s also an infrastructure deficit. Only 17.1% of schools in rural India, for instance, even offer secondary education.

Even those who make it through, sadly, aren’t prepared for the economy. As the survey notes, 75% of higher education institutions lack industry-readiness. This is partly because of poor system design. India’s educational system is built for throughput; it’s built to give the maximum number of certificates possible, rather than fixing learning gaps and building skills.

But part of this also comes from our skewed economy. While most employment is generated in manufacturing, the fastest growing part of our economy is services. Many Indians train for an industry that isn’t built to create mass employment. If anything, the current wave of automation makes this gap worse.

Meanwhile, there’s little emphasis, in our economy, on skilling — which would be better at feeding an industrial ecosystem. Only 4.9% of our youth aged 15-29 has any formal, credentialed training. Most others rely on informal training, which is hard to transfer.

The stakes of fixing this are enormous. This could be what makes, or breaks, India’s bid to becoming an advanced economy.

Distilling the results of Indian alcobev

It’s results time for India’s alcobev companies. The December quarter is traditionally the strongest for alcobev companies, owing to the wedding season. This year was no different.

But, if you read our coverage of the previous quarter, you’d know that the sector is changing structurally. Premiumization, of course, is the biggest trend currently shaping this sector. Beyond that, though, many of these companies are also owning larger parts of the alcohol supply chain. All the while, they’re navigating a fragmented national alcohol market, where each state plays by different rules.

So, we’re looking at the Q3 FY26 results of three major players: United Spirits, Radico Khaitan, and Allied Blenders. Between them, they cover most of the Indian spirits landscape — from mass-market whiskies to luxury single malts.

The numbers

Let’s begin with the headline numbers.

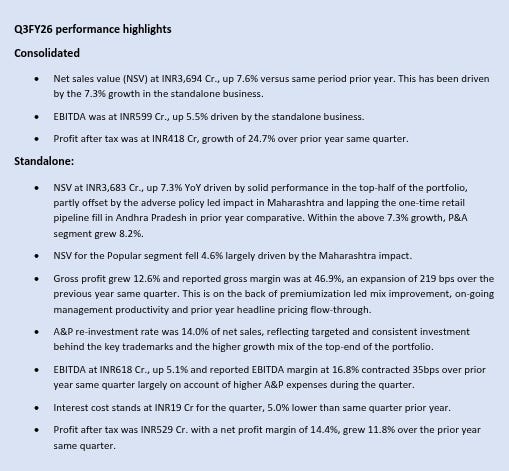

United Spirits (USL), the behemoth of the three, posted a net sales value — or revenue excluding excise duty — of ₹3,694 crore in Q3 FY26, up 7.6% year-on-year. Sequentially, that’s a 16% jump from Q2’s ₹3,173 crore — but that’s largely seasonal, given Q3 is the festive quarter.

The consolidated EBITDA came in at ₹599 crore, up 5.5% y-o-y. However, the standalone EBITDA margins actually contracted by 35 basis points from last year to 16.8%, and fell sharply from the Q2 margins of 21.2%.

The culprit that hurt standalone margins is not hard to find. Often, the festive season accompanies a step-up in advertising spend, and United Spirits spend 14% of net sales on promotions.

Meanwhile, Radico Khaitan, the relative upstart, was the clear outperformer this quarter. Net revenue surged 22% y-o-y to ₹1,547 crore, driven both by its highest-ever quarterly volumes, and an increase in its average selling price.

Impressively, the EBITDA jumped 45% to ₹265 crore, with EBITDA margin expanding by 3 percentage points from last year to 17.2% — the highest margins of all three firms.

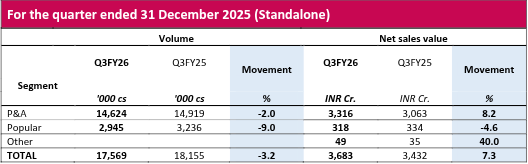

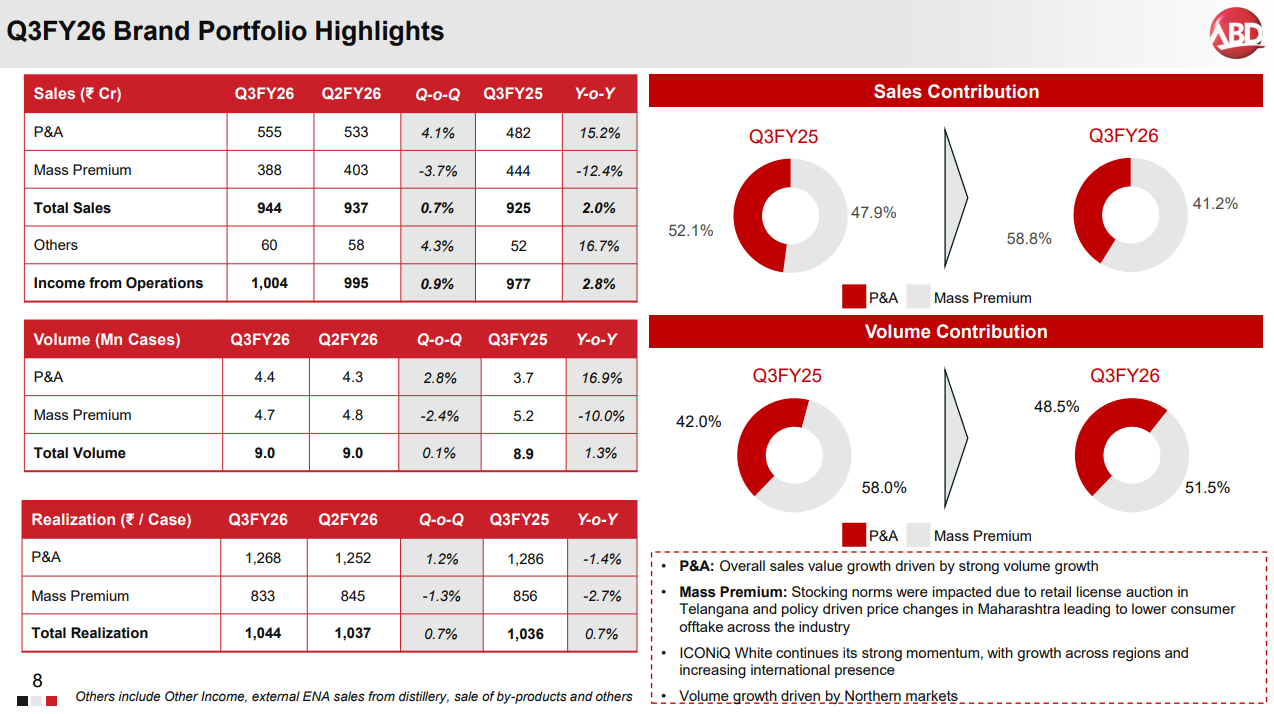

Allied Blenders (ABD) had a more subdued quarter. Consolidated revenue grew just 2.8% y-o-y to ₹1,004 crore, with volumes nearly flat at 9 million cases — up a mere 1.3%. That’s because of a 10% y-o-y decline in volumes in the mass-premium segment.

The absolute EBITDA rose 14% y-o-y to ₹137 crore, with margins expanding 1.3 percentage points to 13.6%. Still, Allied’s margins remain well below its larger peers.

Premium is the new normal?

The variation in margins partially reflects the differences in each company’s premiumization playbook.

Radico’s “Prestige & Above” (P&A) portfolio, for instance, grew 26% y-o-y in volumes, and 29% y-o-y in value. They aren’t just selling bottles that are more expensive, but they’re also selling them in much higher quantities. And this category already makes up nearly 70% of Radico’s sales. Premiumization had a ~36% contribution to the increase in gross margins.

Radico’s portfolio of premium drinks mostly involves whisky, which is India’s favorite poison of choice by far. However, they’ve also tapped into niches like gin and vodka. For instance, as per management, their Jaisalmer brand of gin occupies over half the luxury gin market in India. In the 9 months so far in FY26, Magic Moments, their landmark vodka brand, has nearly touched what it sold in FY25.

The story isn’t very different at United Spirits. The P&A segment makes up 89% of their net sales, and continues to grow. However, their push to premiumization also involves a very real trade-off: iconic mass-market brands (like Bagpiper’s) are being deprioritized.

How do we know that? Well, the net sales in USL’s P&A segment grew by 8.2% y-o-y, despite their P&A volumes falling by 2%. Meanwhile, the popular segment declined 4.6% from last year. That’s no one-off: that’s a reflection of the fact they’d rather sell fewer expensive bottles than sell cheaper ones.

Then, there’s Allied Blenders, for whom the premiumization story is unfolding a little differently.

Now, the premium segment makes up 59% of ABD’s sales — a much lower ratio compared to its peers. They’ve been much slower in making the shift to premium and luxury. In fact, until Q3 FY25, their lower mass premium segment dominated the P&A category in both sales value and volume.

ABD has been historically synonymous with Officer’s Choice, one of India’s largest-selling whisky brands by volume. Even in this quarter, it continues to be the biggest brand ABD holds in terms of bottles sold. And with 45% gross margins, it is also one of the largest drivers of ABD’s profitability and cash flow. That, perhaps, is why they’re still protecting it.

But the direct competitors to Officer’s Choice seem much less attached to their highest-selling brands. Last year, Pernod Ricard sold off Imperial Blue, the third-largest whisky brand in India. Its sales were plateauing, while also dragging down the company’s overall operating margins. They were willing to sell off their cash cows to focus on bigger rewards in the future.

Will ABD be faced with making a similarly hard choice soon? Well, their mass premium segment has been declining in both value and volume over the last year. At the same time, they’re using their mass-market profits to expand their premium category. Their P&A segment posted ~15% growth in sales, more than offsetting the decline of the mass-market brands.

Even if they haven’t made a clean break with their older engines of growth, they’re still moving in that direction. Either way, it’s increasingly clear that going premium might just be the only way to grow.

Backward integration

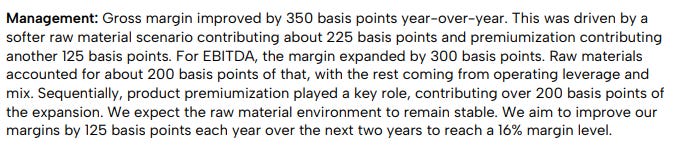

However, premiumization isn’t the only driver of margin expansion. Owning more of the supply chain that feeds the final product has proven to be quite profitable, too.

The key raw material that goes into Indian whisky is called extra-neutral alcohol (ENA). Most companies buy ENA from third-party distilleries, exposing them to volatile swings in ENA prices. The same goes for packaging, like glass bottles and PET bottles, which are often tailored as per the brand’s needs. Often, alco-bev firms end up losing margins because they don’t directly own these inputs.

This quarter, ABD has been extremely aggressive with backward integration. It commissioned a PET bottle manufacturing facility that’s already adding to EBITDA. It is also investing in ethanol distilleries in Telangana and Maharashtra. ABD expects these decisions to improve gross margins by 2.5 percentage points by the end of FY28.

And they have plans for more, too.

Radico, meanwhile, is quite far ahead in its supply chain journey. Earlier, it built a distillery in Sitapur, which is the largest of its kind in Asia. This facility helps secure grain spirits for its premium brands like Magic Moments and Morpheus.

However, Radico hasn’t stopped expanding its supply chain presence. This quarter, it approved a wholly-owned subsidiary in Scotland to secure aged malt supplies for its premium whisky portfolio. Radico is already India’s largest importer of matured Scotch malt; owning a sourcing operation gives it better cost control.

United Spirits, however, is a bit of an outlier in this context. It doesn’t own many ENA distilleries the way Radico or ABD does. It doesn’t even produce raw materials like ethanol or molasses at scale itself. However, that doesn’t imply a lack of supply chain security. It just chooses to pursue this goal differently.

See, for its lower-end products, United Spirits outsources most of the operations to third-parties. But with premium brands, United Spirits owns bottling and packaging units. As far as raw materials are concerned, USL leverages the connections of its global parent company, Diageo. After all, it is one of the largest alcohol conglomerates in the world, is itself backward-integrated, and enjoys long-term supplier relationships.

This allows USL, the Indian subsidiary, to invest more of its capital elsewhere, rather than capex. This keeps their balance sheets asset-light. In fact, over the last few years, they’ve been less debt-laden than Radico or ABD (though Radico aims to be debt-free by FY27).

Inter-state frictions

In our previous coverage of alcohol results, we mentioned how the alcohol market in India isn’t uniform. It heavily differs from state to state. Maharashtra, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh made major changes to their internal market late last year, the effects of which have persisted so far.

Maharashtra’s new liquor policy, introduced mid-2025 imposed steep excise hikes on affordable liquor while carving out a lower-tax category for “Maharashtra Made Liquor“. Essentially, this favors local distillers over national ones.

The impact of this in Q3 was painful for all the companies. It’s partly why, across the board, the volumes of all popular brands declined. When Maharashtra was excluded, growth for all companies looked much healthier.

Telangana delivered a different kind of disruption. In late 2025, the state undertook a new lottery to issue licenses for retail liquor outlets. In turn, older licensees of these outlets temporarily froze buying any stock from alco-bev firms, as they waited to see if they’d keep their licenses. Many of these outlets also kept higher inventory of mass-market brands.

ABD was the biggest victim of this move. After all, Telangana is its largest market, and it saw a 7.4% volume decline in its mass-premium sales. Its more premium-heavy peers were hurt much less by this move. However, this re-auction is just a one-off event — volumes began to rebound in December.

Andhra Pradesh, meanwhile, changed its route-to-market policy, shifting distribution back to private players after years of government control. This affected all three mostly positively, but to vastly varying degrees.

Radico was the biggest winner of this change. AP is a massive brandy market, and Radico’s brandy already had a presence there. When the floodgates opened for private players, it nearly doubled its market share from 15% to 26% in a single quarter. It’s the biggest reason why the volumes of Radico’s mass-market segment surged by a whopping 33% y-o-y.

Both USL and ABD benefited more marginally in comparison. Neither of them had a brandy offering in the state. For ABD, this was the opening of a new market altogether. USL re-entered the AP market only last year after a long hiatus.

The takeaway isn’t that any single state derailed the quarter — all three companies navigated the disruptions fairly well. It’s that regulatory unpredictability is a permanent feature of this industry. Excise policies, distribution rules, and licensing regimes can shift with a change in government or a budget announcement.

Conclusion

The Q3 results confirm that premiumisation is graduating from a trend to a new baseline. Companies that can’t credibly compete in the premium segment will find themselves squeezed between cheap local options and aspirational national brands.

Radico has emerged as the momentum story, with margins now exceeding United Spirits and a premium portfolio gaining serious traction. United Spirits is betting that heavy brand investment will pay off in market share and pricing power. ABD faces the classic challenger’s dilemma: it needs to invest aggressively to close the gap, but execution risk is high.

Tidbits

The Finance Ministry is holding inter-ministerial consultations to raise the FDI cap in public sector banks to 49% to strengthen their capital base.

Source: Reuters

Passenger vehicle wholesales grew over 11% year-on-year to approximately 4.50 lakh units in January 2026, driven by record despatches from Maruti Suzuki and strong growth from Mahindra and Hyundai.

Source: The Hindu

Advent International will pick up a 14.3% stake in Aditya Birla Housing Finance for ₹2,750 crore, valuing the mortgage lender at ₹19,250 crore.

Source: BS

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Just to confirm,

The article says: ".....Without that, however, states’ own investments have fallen considerably since FY 2022, from 2.11% to 1.92% of GDP...."

Since theres a revenue deficit of 0.7%, meaning states are unable to even afford salaries, pensions etc., this capital outlay of 1.92% if also coming from borrowings?

I couldn't agree more with your analysis of the current prospects for India. It is deplorable that politicians have been given the right to decide everything in India, and promptly take decisions that only benefit themselves -- never their electorate as a whole. Another truth that the Indian experiment with democracy has unearthed is that our legislators simply cannot cooperate with each other. They ignore good recommendations and useful warnings, and excel at heckling and squabbling with each other at every turn, something that is shameful to see. As such, our attempts to move ahead are doomed from the start.

I believe that a good first step in India would be to teach everyone English, and make our teaching methods and teacher training world-class. That way, the peoples of our vast population would at least understand each other a little better. I have seen its transformative power in South East Asia, where they have openly acknowledged the need for English, and embraced best practices in foreign language learning. With a common language base, the systems and syllabi in education here will definitely move and work more easily.