Can India break this Pharma Monopoly?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Can Novo Nordisk defend its turf?

What exactly are “water stocks”?

Can Novo Nordisk defend its turf?

Last week, we talked about the fascinating world of India’s generic drug manufacturers.

We spoke about how India had found a niche for itself in the pharma industry — Indian companies learnt to puzzle out how to re-create drugs that global pharma majors had discovered. With that, they created an industry around selling those drugs the world over, for cheap.

While those efforts might make it cheaper for others to get the healthcare they need, naturally, not everyone’s happy. Companies drain billions of dollars and many decades into creating a single drug. When they hit upon something valuable, they’re willing to fight tooth-and-nail to protect their turf. Anyone who makes generic drugs, of course, comes right in their cross-hairs.

We saw this play out a few days ago. Novo Nordisk, the maker of blockbuster drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy, just went after two Indian companies, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories and OneSource Specialty Pharma, before the Delhi High Court. The claim: these companies were making Semaglutide, the active ingredient that makes drugs like Ozempic work, without its permission — a violation of its patent rights.

Here’s everything you need to know to understand this case.

Sizing the stakes

Since the 1970s, scientists have been playing around with the drugs that hit at the body’s GLP-1 receptors, to see what effects. At first, they thought these would help with stomach ulcers. Somewhere down the line, they began taking it seriously for diabetes management. That’s what it was intended for when Semaglutide was first approved as medicine. As recently as 2021, Ozempic wasn’t even in the world’s top 20 best-selling drugs.

By the time this decade rolled around, however, Novo Nordisk had started realising just how big a goldmine it was sitting on. By March 2021, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the evidence had become incontrovertible. Semaglutide helped people lose weight. It wasn’t something you could only sell to people who were grievously sick. To the contrary, it was the answer to weight management issues, a problem that 43% of the world’s adults dealt with. The company’s potential market was orders of magnitude larger than what it had once imagined.

A flood of money soon started flowing in. Last year, Novo Nordisk saw its revenues rise to $40.6 billion. Ozempic became the world’s second best-selling drug in 2024, losing only to the literal cure for cancer.

But it has a problem: others want a slice of this multi-billion dollar pie as well.

And they’ve spotted a key vulnerability. Because Novo Nordisk is soon slated to lose its legal monopoly over its weight loss drugs in much of the world.

Patents and Novo Nordisk

Under the standard rules of capitalism, if you run a business that mints a lot of money, others are allowed to copy whatever you do and take some of that money for themselves. This is, by and large, a good thing. A competitive market is simply better at keeping businesses on their feet, and giving customers what they need for the lowest possible cost.

But this isn’t an unalloyed good. If people create something completely new, you probably want to protect them from copy-cats. Without that, people will either keep any breakthroughs a secret from the rest of the world, for fear of them being stolen — or worse still, they might see no point in innovating altogether.

And so, when people create something new, governments sometimes award them monopolies, through what is called ‘patents’. A patent guarantees that, at least for a few years (twenty years, usually), you’re the only one who can sell your creation and earn money out of it. Think of patents as a bargain that society makes: if you come and tell us about your novel ideas, we’ll keep them safe from your competitors for a few years.

Of course, this can get complicated once you start to really think about it.

Consider this, for instance: what do you really mean by “creating something new”? If you create something that’s obviously an invention — like the world’s first electric car, for instance — you can definitely patent it. But most patent applications are meant for things that are a lot more niche. Imagine, for instance, that someone creates a special motor that uses an extra magnet to make electric car powertrains marginally more efficient. Have they really created anything? How would you even tell?

Courts usually look at two criteria: one, what you’re trying to get a patent over is ‘novel’ — that is, it has never been seen before; and two, that it is non-obvious — that is, you’ve actually made an advancement of some kind, instead of just hacking together something anyone could have come up with. But this, too, doesn’t necessarily clear things up.

You see this a lot in pharmaceuticals. Pharma companies basically make chemical compounds, and those allow for nearly endless variation. It’s in the best interest of a pharma company to tell you that whatever change it makes is novel and inventive, and should get a patent. They’re chasing monopoly profits after all. But these variations are so specific that regular people would simply have no idea if they’re worth patenting.

Take Novo Nordisk:

The company first discovered how to make a class of “GLP-1 analogues”. At this point, it tried to secure rights over a broad set of related chemicals that could all be made by swapping around different building blocks. It got patent protection over these until 2024.

Soon afterwards, the company made a few changes — substituting an amino acid, and adding a fatty acid on the side — to specifically create Semaglutide. These changes, it claimed, made the chemical more stable, and made it easier to absorb. It got an additional patent over this until 2026.

And those are just two. These are all the patents the company has in the United States:

Is Semaglutide truly new? Were these changes so inventive that they deserved a separate patent of their own? Do you really have something novel if you shift around a dozen atoms in a molecule, while keeping its hundreds of other atoms the same? How does one even begin to answer these questions?

We genuinely don’t know. We’re a team of bloggers and Youtubers — we can’t tell you the first thing about what is new or inventive about one of the most advanced drugs in the world. And if we tried, you should know better than to listen to us.

What we can tell you, though, is that billions of dollars hang on the answer to this question.

The challengers take position

Even for companies that make patented drugs, Novo Nordisk is in a weird position.

For most of the life of its patent, it thought it had a monopoly over an excellent blood sugar medicine. The clock on its monopoly began all the way back in 2006. In most of the world, that clock would run for twenty years — that is, till 2026 — unless it managed to negotiate extensions. And yet, only in the last few years did the company realise the real potential of its drug. Despite discovering what might be one of the most important pharmaceutical molecules in the world, it barely had five years to cash in.

Sales of the drug gathered most of its momentum in 2023. Novo Nordisk is yet to tap major markets — until recently, for instance, it only planned to introduce Semaglutide drugs to India in 2026. That is, incidentally, the very year it loses patent rights over Semaglutide in the country, as well as other massive markets like China or Brazil.

Of course, others understand this only too well.

A range of pharma manufacturers across the world have set their sights on that 2026 deadline. In China, for instance, at least 15 companies are trying to create something similar — with hopes of bursting into the scene as soon as Novo Nordisk’s patent expires. Brazil’s Hypera, too, is working on a generic alternative to Semaglutide.

India, as the pharmacy of the world, has similar plans. Many of our own pharma majors are eyeing the space as well.

In fact, Indian companies even took this fight to the United States. Last year, Novo Nordisk tried to sue Indian companies — like Natco Pharma and Sun Pharma — for infringing its patents. In response, Indian companies threw their own counter-punches, opening up Novo Nordisk’s American patents and asking the country’s patent board to revoke them. The threat was real enough that Novo Nordisk settled, even giving out sops like an exclusive ‘first-to-file’ status to some.

One of the Indian frontrunners in the race to develop weight loss drugs is Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories — one of India’s biggest generic drugs manufacturers. We had written, late last year, about its foray into the space. Last October, the company got a license from the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), to start studying how it could replicate Semaglutide. It then teamed up with OneSource Specialty Pharma, a CDMO (we wrote all about those last week) to get its production line in place. Once Semaglutide became fair game, it would be first in line to make it.

But soon, they went even further, doing something particularly interesting. This April — one year before Novo Nordisk’s patent expired, and before they got a license to sell anything from Indian regulators — they already began manufacturing the drug.

The fight erupts

This April, Novo Nordisk made a big announcement. It would advance its entry into India — launching in the next couple of months, rather than waiting till next year, as it originally thought. Arch-rival Eli Lilly had already made its entry, and the space was heating up too much for comfort. The company hoped to make the most of the last year of its protection.

Dr. Reddy’s greeted the announcement with a court case.

On May 14, Dr. Reddy’s went to the Delhi High Court, claiming that Novo Nordisk’s patent over Semaglutide should be revoked. They claimed that the company already had a patent on GLP-1 analogues, where all its real innovation happened. But that patent had expired in 2024. Semaglutide, they argued, added nothing. This was just an attempt at “evergreening” — where pharma companies kept filing newer and newer patents to extend their monopoly over a drug.

If it succeeds, it would basically nullify any first-mover’s advantage Novo Nordisk had in the country.

On May 26, Novo Nordisk countered by filing its own lawsuit before the Delhi High Court. It claimed that Dr. Reddy’s was out to breach its patent rights over Semaglutide. It was manufacturing and exporting the drug without permission — essentially ignoring its patent rights.

On May 29, the Delhi High Court came out with a temporary set of rulings — what lawyers call an “interim order.” Here’s what it decided:

For now, Dr. Reddy’s can’t sell Semaglutide in India.

At the same time, Dr. Reddy’s can produce Semaglutide here, as long as it’s only making the drug to sell abroad.

Basically, Novo Nordisk has ensured that Dr. Reddy’s won’t step on its turf as far as the Indian market is concerned. But it failed to protect them from going after other markets, where it doesn’t have the same patent protections. As things stand, Dr. Reddy’s could potentially start by exporting generic GLP-1 drugs, build up its competence, and then grab the Indian market as soon as it has the legal clearance to do so.

Now, this isn’t the court’s final take on the issue. The court’s simply telling everyone what to do while it takes its time to mull over things.

Novo Nordisk, though, isn’t happy with this halfway compromise. Under the law, it believes, if you have a patent over something, it’s not just that others can’t sell it. They can’t “make” it either. This isn’t completely unfounded. In similar cases in the past, the Delhi High Court has stopped companies from manufacturing patented drugs for export, even though they weren’t selling anything here.

But none of that will matter if Dr. Reddy’s succeeds in getting its patent cancelled in the first place.

What happens now

Frankly, when we started learning about India’s pharmaceutical generics industry last week, we didn’t expect to see such a perfect demonstration of how the incentives of different players lie. Because the truth is, the position of both sides is a simple product of what they do.

Novo Nordisk is doing what any company in its position would do: it’s trying to defend the commercial edge it has on a proprietary innovation that’s become unexpectedly valuable. And Dr. Reddy’s is doing what generic manufacturers have always done: pushing at the legal limits of what’s protected, and what isn’t — hoping that, when the dust settles, they’re in a position to rip through the industry.

The Delhi High Court has tough decisions before it. It will now have to decide whether the patent over Semaglutide is one that ought to be enforced, and if so, where do the limits of those rights lie. But even if the court sides with Novo Nordisk for now, its monopoly will be short-lived. Come 2026, the patent will expire, and Indian companies will almost certainly enter the market.

The only real question is: will Novo Nordisk be able to get its foot through the door before that happens?

What exactly are “water stocks”?

There are plenty of everyday essentials we barely think twice about.

Take utilities, for example. Electricity, internet, phone calls — these are things we use daily without even noticing. But behind each flick of a switch or tap of a phone screen, there’s an entire world of companies, governments, and individuals working tirelessly to make these conveniences possible. It’s genuinely fascinating once you start peeling back the layers.

Off late, over at The Daily Brief, we’ve been going down a series of these rabbitholes. Recently, we explored telecommunications and were blown away by all that happens behind the scenes, just so we you effortlessly talk to a friend or stream our favorite show.

And today, we ended up looking at something even simpler: where does our water come from?

See, lately, we’ve seen companies like VA Tech Wabag and Ion Exchange pop up in conversations and news headlines, labeled as promising “water stocks.” But to be honest, when we tried to understand exactly what these companies do, we felt pretty lost. There was so much technical jargon and complex background information required just to make sense of how water even gets from one place to another!

So, we decided to start from the basics. We asked ourselves some fundamental questions: How does water actually flow into our taps each day? What happens to it after we use it? And where exactly do these “water stocks” fit into the entire water cycle? And beyond that, we wanted to understand the companies that are part of this journey, and how they make their money.

Here’s what we learnt.

How does water come to your tap?

It’s easy to take water for granted — turn the tap, and out flows clean, clear water. That’s about as much as most people think about it.

But behind that simple convenience is a remarkable journey.

It starts from a far away water source — often in a river, a lake, or deep underground in an aquifer. That raw water — still full of natural sediments, microbes, and all sorts of invisible impurities — is first drawn into what’s called a Water Treatment Plant, or WTP. Here, that water is cleaned up:

First, the water is screened to remove larger debris like leaves, sticks, or stray plastic wrappers.

Next comes a fascinating chemical process, called coagulation and flocculation — a fancy way of saying tiny particles are encouraged to clump together, forming larger pieces that settle down easily.

Then, the water moves through filtration, usually layers of sand and gravel that capture even smaller impurities, leaving the water clearer than before.

But it's not ready yet. To make sure it’s safe to drink, the water undergoes disinfection, where chlorine or ultraviolet (UV) light eliminates harmful bacteria, viruses, and microbes.

Once thoroughly cleaned, the water is tested rigorously, pressurized, and finally pushed out into a vast underground network. This intricate maze of pipes, pumps, valves, and reservoirs — often stretching hundreds of kilometers — channels water directly into our homes, offices, factories, and farms.

And that's how water finally arrives at your tap.

Or that’s at least how it’s supposed to happen. Some of you might live in places without this critical piece of infrastructure, depending on water mafias to drive by with tankers full of water. But let’s leave that aside for now.

Anyway, the story doesn’t end once water gets to your house. Because once that water’s been used — whether it’s washing your hands, doing the laundry, or flushing the toilet — it becomes wastewater. This is dirty, used, and potentially hazardous if left untreated.

So, it enters another hidden system: the sewers. These underground pipelines collect all that used water and channel it to another facility: the Wastewater Treatment Plant. (And yes, we get it, this bit of infrastructure is missing too, in most of our country. Once again, let’s leave that aside.)

The process here is kind of like running the dirty water in reverse.

First, the big stuff — think sanitary waste, food scraps, or even grit from the street — is removed.

What’s left, then, flows into ‘settling tanks’. Here, heavier materials sink to the bottom and oily scum floats to the top.

Next, the water meets an army of microbes — tiny bacteria specially cultivated to munch on the remaining organic matter. These little helpers are given oxygen and time to do their job, breaking down waste into safer components.

Once their work is done, the water goes through another round of settling, and then—depending on the plant—an extra step of filtration and disinfection.

At the end of all this, what was once wastewater is now treated effluent — clean enough to be released into a river or lake, or even reused for irrigation, construction, or industrial cooling.

What happens to all the solids and sludge? Those go through a different process entirely — often turned into compost, fertilizer, or even biogas for electricity.

But wait—where exactly are these “water stocks”?

Okay, we admit that was quite a deep dive. But trust us, this context was necessary. Here's why.

In India, water is considered a public good. Managing both water supply and wastewater treatment falls under the responsibility of local municipalities and state governments. Essentially, they’re the ones making sure water reaches your home, and that your wastewater is treated safely.

But governments and municipalities can't handle everything alone. The infrastructure needed — pipes, pumps, valves, massive treatment plants — is extensive and often highly specialized. Sometimes, they struggle to get this together.

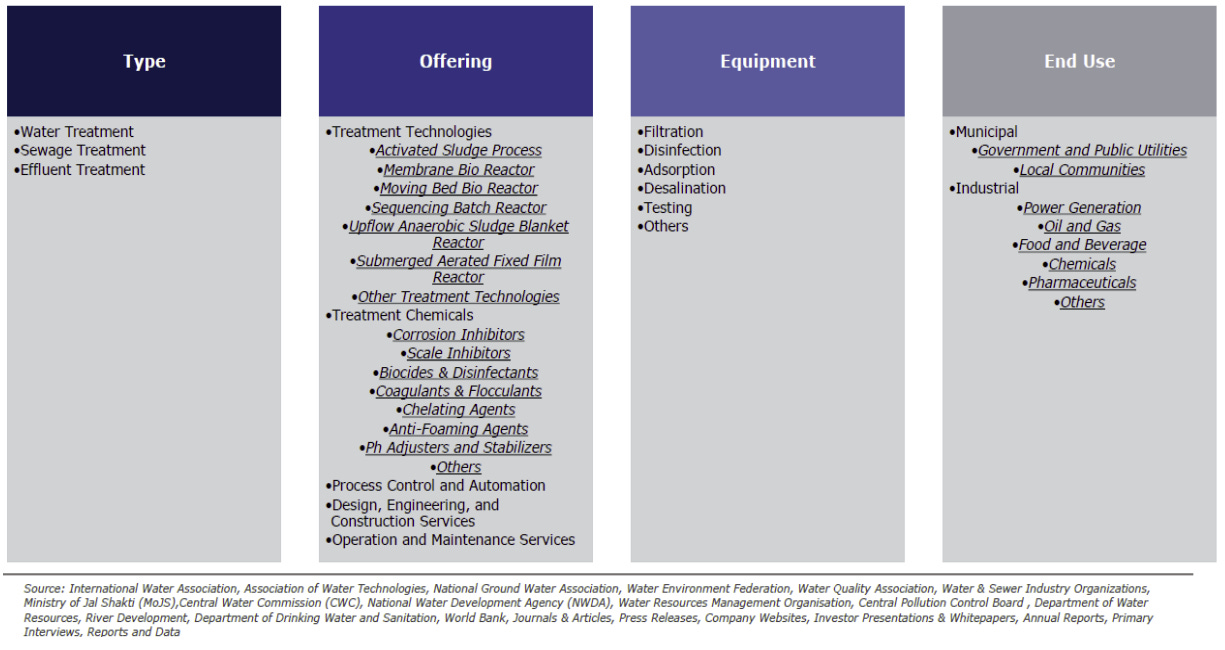

But even if they do their job perfectly, a lot of this requires private companies to pitch in — or as the stock market calls them, “water stocks.” These private companies step in at every stage — from sourcing water from rivers or underground aquifers, to treating it, and finally discharging it safely back into rivers or lakes. They help governments by designing, building, operating, and even maintaining this infrastructure.

Here's how that plays out practically: Imagine a city needs a new water treatment plant. A private company will offer its expertise to design and build that plant — providing Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) services. We wrote about this recently. Once built, the same company might even run and manage the project for several years.

Meanwhile, other companies might supply the specialized equipment, or provide chemicals for treating water, or even consulting services to ensure the plants are efficient and compliant with regulations.

Usually, these companies cater to the government — central and state governments, as well as local urban bodies (municipal corporations, water supply and sewerage boards). These entities typically oversee major water projects. They plan service coverage, set tariffs for consumers, and secure funding. Private companies simply plug into the ecosystem they create.

But apart from plugging into government infrastructure, sometimes, private companies also cater directly to industries — that must treat their wastewater before safely releasing it into the environment. Once again, they provide not just physical equipment but also critical services and chemicals needed to purify water to strict standards.

Simply put, anywhere there's water infrastructure involved, there's likely a private company working behind the scenes to make it possible. While these assets and infrastructures typically remain under government ownership, it's these private players that truly make the whole ecosystem function.

And that’s the big investment opportunity behind water stocks.

We aren't huge fans of tossing around big numbers just for the sake of it, but here, the scale is the story. The Indian water industry — covering everything from water treatment technologies and essential chemicals, to EPC and ongoing operational services — is valued at approximately $13 billion. And it’s expected to grow steadily at about 6% per year over the next decade.

A lot of this sector’s future depends on government policy.

For example, the Jal Jeevan Mission (2019–2024) for rural water supply, and the AMRUT scheme for urban renewal have both allocated massive budgets to build out water supply systems and sewage treatment facilities across India. These schemes often come with guidelines that encourage engaging private firms via tenders, while the funding is largely public (center or state grants). If you’re evaluating what happens to the sector, these schemes are a good place to start.

Let’s talk companies

The Indian water infrastructure ecosystem includes a mix of dedicated water companies, diversified infrastructure firms, and niche technology providers. Some of the major players (especially those listed on stock exchanges) are:

VA Tech Wabag Ltd:

Wabag specializes in the design, engineering, and operation of water and wastewater plants, with over 6,500 projects completed globally. The company positions itself as a technology-focused EPC and Operations and Maintenance (O&M) player, rather than a civil construction firm. In fact, Wabag’s strategy in recent years has been to go asset-light and high-tech. It prefers to focus on things that require intellectual capital — process design, engineering, and equipment integration — while subcontracting the actual civil works.

Wabag O&M order book provides it a source of recurring revenue. In such contracts, companies operate plants for decades and recoup their investment through periodic payments — either by the government (e.g., the city pays per litre of wastewater treated) or directly from consumers/users through tariffs (less common in water in India due to low water tariffs). Almost 45% of its order backlog is O&M/contracts, balancing the 55% EPC portion. This recurring income smooths out the lumpiness of the revenues it earns from projects. O&M orders let companies run

Ion Exchange (India) Ltd:

Unlike Wabag, which is primarily project-focused, Ion Exchange does a little bit of everything: it manufactures ion exchange resins, membranes, and water treatment chemicals; it supplies water treatment equipment; and it undertakes turnkey projects (EPC) and O&M services. The company serves industries, institutions, homes, and communities, covering everything from large plants to household water purifiers.

Other Notable Players

Infrastructure EPC Firms: Companies like Larsen & Toubro (L&T), SPML Infra, and newly listed EMS Ltd undertake water supply and sewage projects for cities.

Equipment and Component Manufacturers: There’s a large set of companies that create the equipment needed for water infrastructure. These include pump makers like Kirloskar Brothers or Shakti Pumps — a business with healthy margins. There are also valve and piping companies. Welspun Corp, for example, is a big player in manufacturing pipes used in water projects, with a robust order book for water pipelines. Similarly, Jash Engineering provides water control gates, screens, etc., used in treatment plants and dams, with very high profitability on those niche products.

Now, we know we completely skipped different business models that companies operate in, or various technologies they are working on. This is just meant to get you started with the basics.

Wrapping Up

India’s water infrastructure sector is unlike the same sector elsewhere in the world. We’re still a country that’s building out our pipelines. And so, players in the sector are high-growth and policy-driven, in contrast to the more mature, steady state sectors in developed economies.

And that’s why India offers a unique chance in a sector that most would overlook: a chance to participate in building essential infrastructure for a sixth of the world’s population. This is a place where you can buy into India’s development sector, while also selecting for significant business potential. We’re a long way from living in a country where every Indian has access to clean water, and eventually, it is these “water stocks” that will get us there.

Tidbits

Yes Bank to Raise ₹16 thousand crore; SMBC’s ₹13.48 thousand crore Deal Adds Global Muscle

Source: Reuters

Yes Bank has approved plans to raise up to ₹16 thousand crore, comprising ₹7.5 thousand crore through equity and ₹8.5 thousand crore via debt in Indian or foreign currency. The total equity dilution, including any conversion of debt into shares, has been capped at 10%. This capital raise follows a major deal last month where Japan’s Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) agreed to acquire a 20% stake in the private lender for ₹13.48 thousand crore. The SMBC transaction, involving eight existing shareholders including SBI, is being touted as the largest cross-border M&A in India’s financial services sector. While the bank has not disclosed the specific use of the funds, the twin moves reflect a significant capital and strategic development for the institution.

Maruti Suzuki Scales Up Solar Capacity to 79MWp, Targets 319MWp by FY31

Source: Business Line

Maruti Suzuki India Ltd has commissioned two new solar projects totaling 30MWp—20MWp at its greenfield Kharkhoda plant and 10MWp at its Manesar facility—raising its total installed solar capacity from 49MWp to 79MWp within a year. This marks a 61% year-on-year increase in captive solar power generation. The company has outlined a roadmap to expand this capacity further to 319MWp by FY2030-31. Supporting this transition is a planned investment of ₹925 crore. Maruti Suzuki aims to meet 85% of its electricity needs from renewable sources by the end of the decade. The initiative also aligns with Suzuki Motor Corporation’s global Environment Vision 2050 and reflects a broader focus on green energy procurement alongside self-generation.

Schloss Bangalore Secures ₹1,302 Cr BKC Plot for Luxury Hotel Project

Source: Business Line

Schloss Bangalore has received an allotment from the MMRDA for an 8,412 sq.m plot in Mumbai’s Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC) to develop a 250-key luxury hotel. The lease period is set for 80 years, with a total lease premium of ₹1,302 crore. As per the terms, 25% of the lease premium is to be paid within two months, while the remaining 75% will be paid over the next ten months. The land allotment has been made to Schloss Bangalore and its consortium partners, whose names were not disclosed. This development coincided with Schloss’s stock market debut, where shares listed at ₹406.50 on the BSE, marking a 6.55% discount to the IPO price of ₹435. The project is part of the company’s expansion into key urban luxury markets.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉