The stationery industry has plenty of ink left in it

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads-up before we dive in. The Wakefit IPO is open now. We wrote about them earlier — you can read the full story on Wakefit here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

A nostalgic dive into the stationery business

How did India’s public-sector oil firms do this quarter?

A nostalgic dive into the stationery business

While researching for The Chatter, we stumbled upon the business of stationery brand DOMS. It’s been listed in India for a couple of years, but we never gave it much thought. How exciting can pencils and erasers really be?

But then, we discovered that in 2023, besides DOMS, two more stationery companies (Flair and Cello World) hit the stock market. This got us reminiscing of those childhood days visiting stationery shops before the new school year. The smell of new notebooks, the rainbow of pen colors, the all-important decision of which pencil box to buy — it was almost a ceremonial ritual.

So, we thought: why not take a fun, conversational deep dive into the stationery industry itself?

Now, fair warning: this industry isn’t exactly the next tech boom. In fact, there are very few investable options here — not many big listed companies, in India or globally. It’s also extremely fragmented, full of many small players. But that’s why it’s intriguing in its own way.

Let’s break down the humble stationery market.

The product

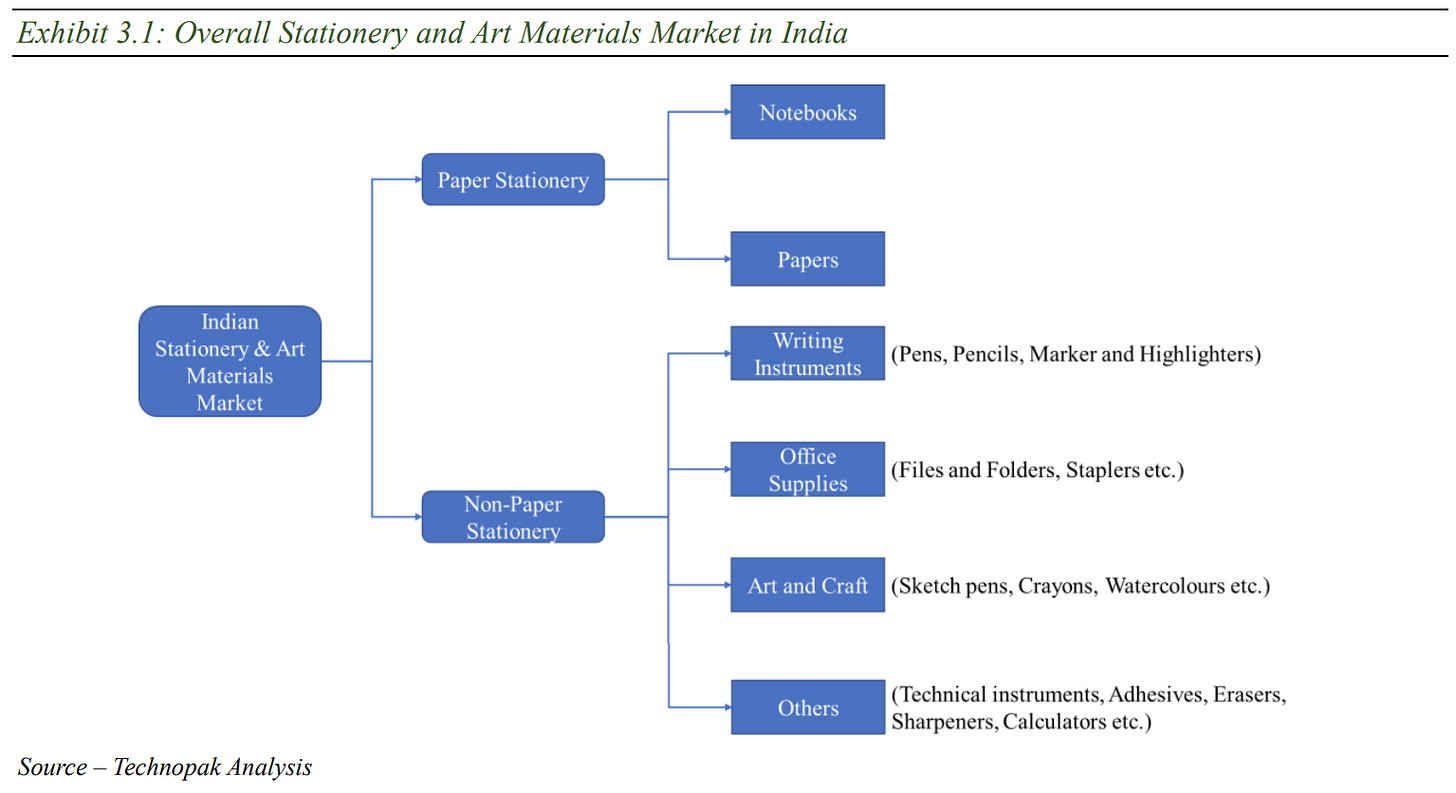

Broadly, the stationery industry is split into paper stationery and non-paper stationery.

Paper stationery includes things like notebooks, writing pads, drawing books, loose paper reams. In India, notebooks form the bulk of this segment by value. Paper stationery makes up ~42% of the Indian stationery market by value and is a pretty commoditized segment. After all, a notebook is a notebook, right?

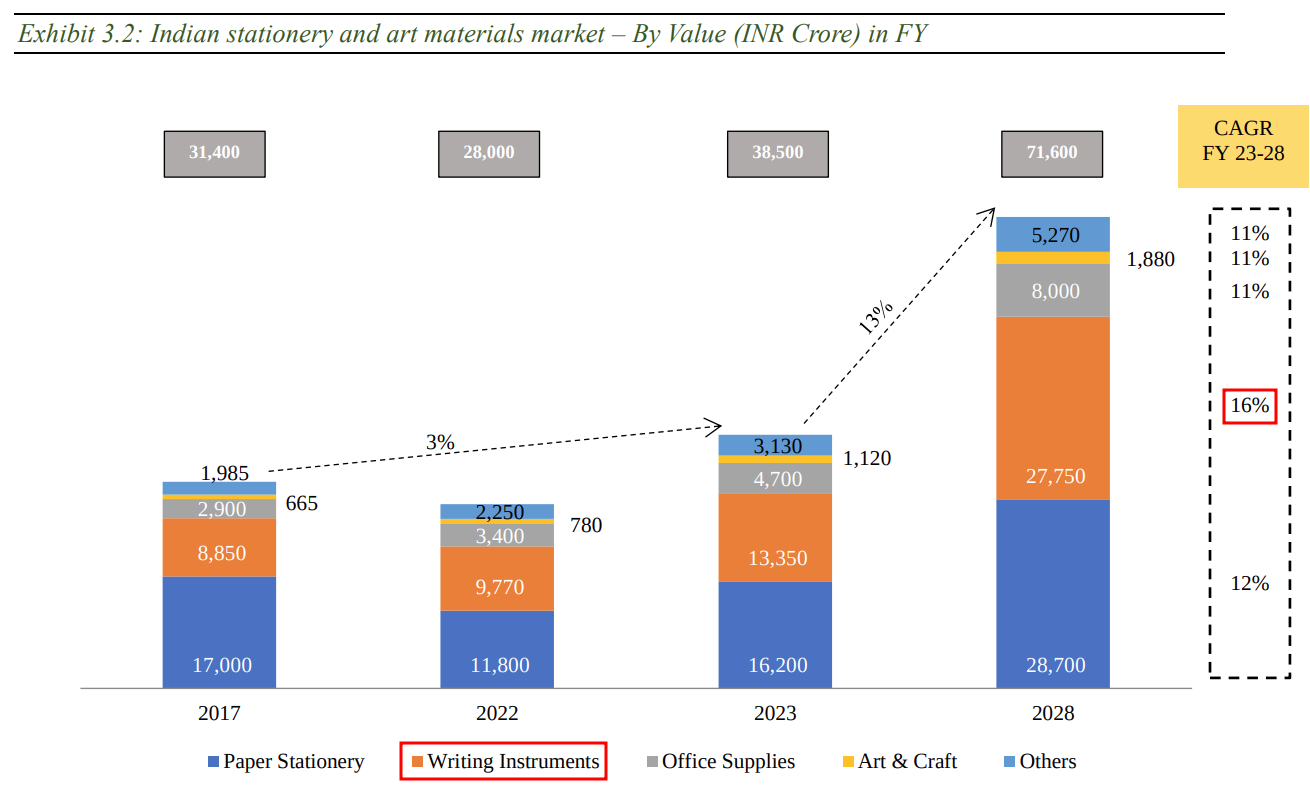

Non-paper stationery covers all the other goodies — pens, pencils, erasers, sharpeners, rulers, crayons, art supplies, files, staplers, glue, you name it. Non-paper products are actually the larger share of the market — about 58% by value as of FY23. And within this, the writing instruments category (pens, pencils, etc.) is the biggest and fastest-growing chunk.

The target consumer

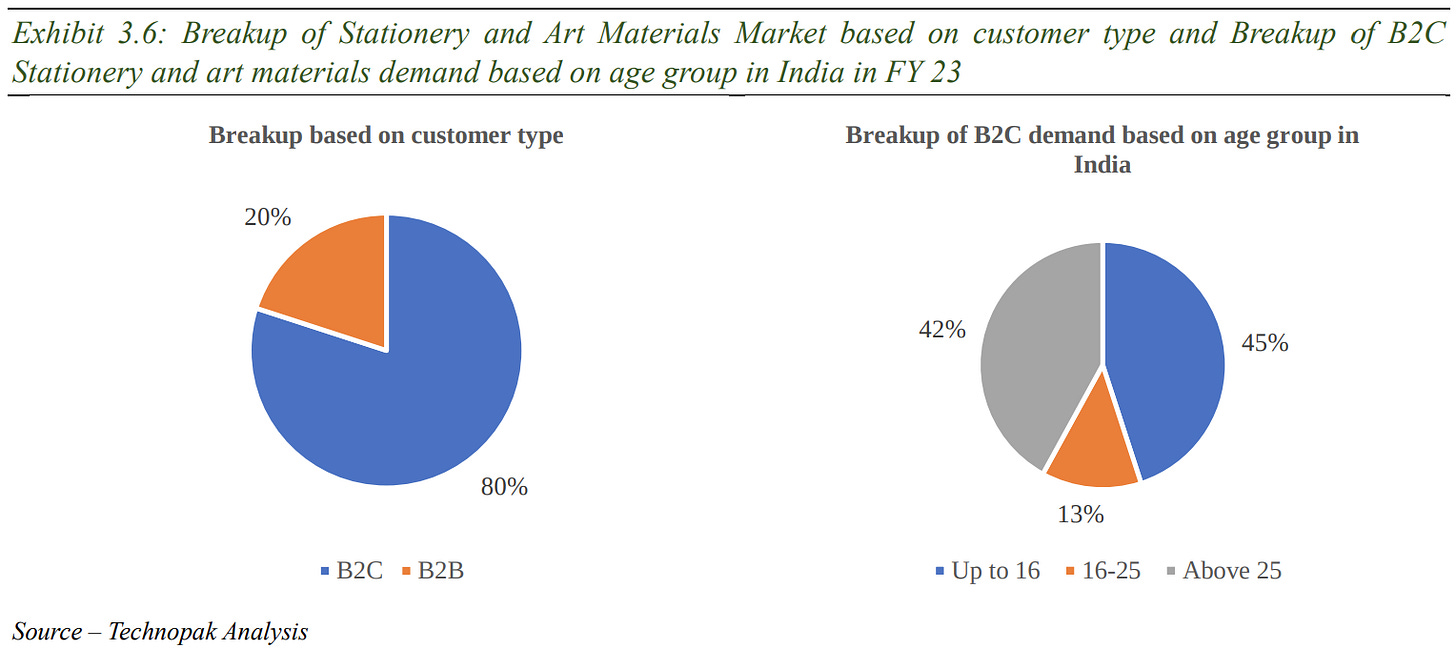

So, who buys these products and through what channels? ~80% of stationery demand is driven by individual consumers like students and professionals (B2C), while ~20% comes through bulk institutional orders from schools, colleges, and corporates.

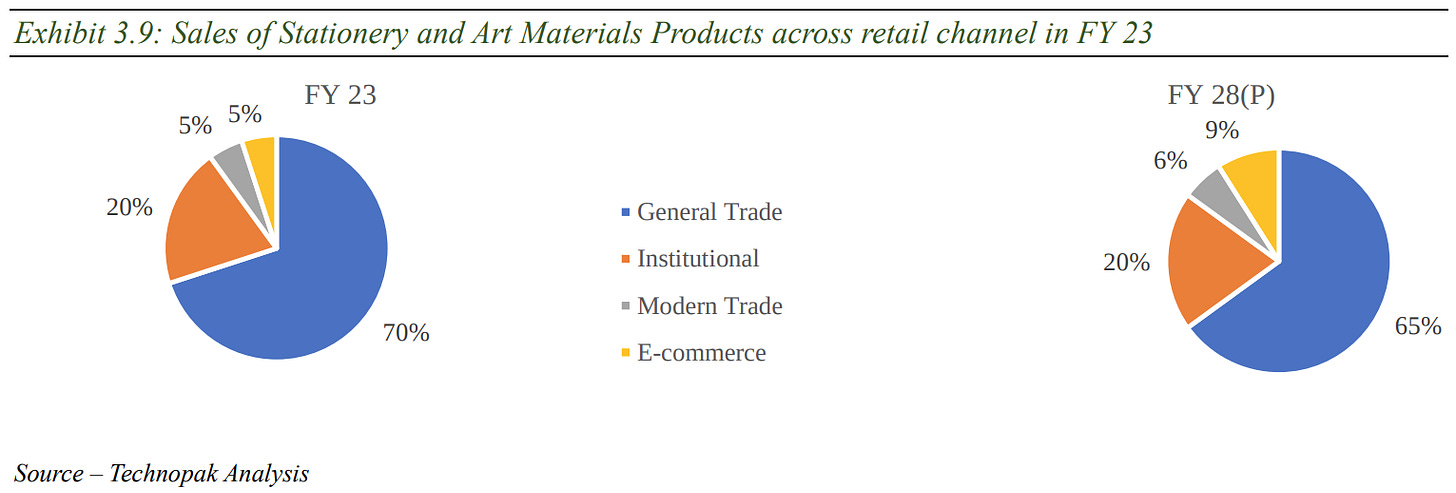

Now, how do these products get to the end customers? The stationery business in India is still dominated by good old mom-and-pop shops — the general retail stores and small stationery outlets in every market. General trade channels make up ~70% of sales.

After that, ~20% is direct institutional sales — meaning manufacturers or distributors selling directly to big buyers like schools, offices, government agencies etc. Only around 5% of sales each come from modern retail chains (think Dmart) and from e-commerce.

This is interesting, because unlike other FMCG categories, stationary is untouched by the phenomenon of quick commerce taking a larger share of the trade from the kirana ecosystem. The industry is still highly fragmented and unorganized.

This also means that distribution is absolutely key. You want your stationery products in as many of those mom-and-pop stores as possible. A large, efficient distribution network is critical to capture the market — we’ll learn more about this later.

The business model

Let’s talk about how the money flows in this business. When you buy a pen or a notebook, it’s obviously a one-time transaction — you pay a few rupees, get your item, end of story. There’s no subscription or service fee here.

However, the nature of the product is consumable and recurring. Your pen will run out of ink, your notebook will get filled, your eraser will get used up (or mysteriously disappear, if you’re like we were in school 😄). That means customers come back for more, repeatedly.

In a sense, stationery has a built-in repeat purchase cycle.

As long as there is a constant inflow of students going to school, there’s continuous demand. But, since pens are commoditized low-value products, volume matters far more than value. You need to sell millions of ₹10 pens to make any real money. A company’s growth often comes from either selling more pens/pencils each year, or introducing slightly higher-value products — like a premium pen at ₹90.

There is also a seasonality factor tied to the school calendar. Think about when you used to buy most of your yearly stationery — likely at the start of the academic year. In India, many schools start the new session around March-April, and some colleges in July. This “back-to-school” season triggers a big spike in sales of notebooks, pencils, school kits, etc. Companies often see a huge uptick in Q1 of the financial year thanks to this seasonal buying.

The distribution game

We hinted at distribution earlier, but let’s dig deeper into why it’s so important. The typical supply chain looks like this: brands produce the items (or get them made), then sell to distributors/wholesalers, who then supply to retailers (stationery shops, bookstores, supermarkets), and finally the product reaches us customers. Companies might bypass and sell directly to big institutions or via e-commerce, but that’s a very small slice.

Now, one might think that a company should invest a lot in advertising to build a brand. But, unlike soft drinks or phones, point-of-sale visibility and dealer “push” often matter more in stationery than glitzy ads. Why? Because as a consumer, you generally don’t plan much before buying a ₹10 pen or a pencil — you buy what you see in the shop, or whatever the shopkeeper recommends. The products are quite similar and interchangeable in function, so spending on glitzy ads doesn’t make a lot of sense anyway.

So, stationery companies channel a lot of effort into making sure their product is available and visible at the retail counter. They offer margins and incentives to distributors to stock and push their brand.

In contrast, mass media advertising is limited in this space. You’ll occasionally see an ad, especially targeted at kids (like fancy pencils or crayons ads on kids’ TV channels). But, it’s not a huge spend area for most players. Instead, money goes into expanding the distribution network or geographic reach. That’s why companies like Flair and Camlin boast more than 3 lac+ touchpoints.

The economics also favor distribution spending because brand loyalty is modest.

We might have our personal favorite pen or notebook brand, but if the shop doesn’t have it, we’re usually fine buying an alternative. Which also means that switching costs are near zero — if Brand A’s pen runs out or isn’t there, Brand B’s pen writes just as well for our needs. This makes the industry highly price-competitive and limits pricing power. Manufacturers can’t really charge a premium; unless it’s a differentiated product altogether.

Easy to learn, hard to master

At first glance, making stationery doesn’t seem like rocket science. Entry barriers are relatively low on the manufacturing side. You don’t need super-advanced tech or massive capital to start a small-scale pen or pencil factory. A modest investment, some machinery, access to plastic or graphite or paper — and you can start producing. The knowledge required is not very specialized. That’s why India has hundreds of local, unorganized players.

However, the story changes when you try to scale up to a national brand. To really compete with the big boys, you need to overcome significant hurdles: achieving economies of scale, investing in larger production capacity, and building extensive distribution networks across India.

And establishing a pan-India presence is tough. Think about it – you’d have to reach tens of thousands of retail outlets spread over 28 states, all while competing for shelf space. This requires a sizable sales force, a network of distributors, logistics management, and marketing effort. That costs money and time, and it’s not something a newcomer can do overnight.

In sum, it’s easy to enter the market in a small way (low entry barrier), but it’s hard to scale and survive at the top (high entry barrier for scale). Many small fish can swim in the pond, but growing into a big fish is the real challenge.

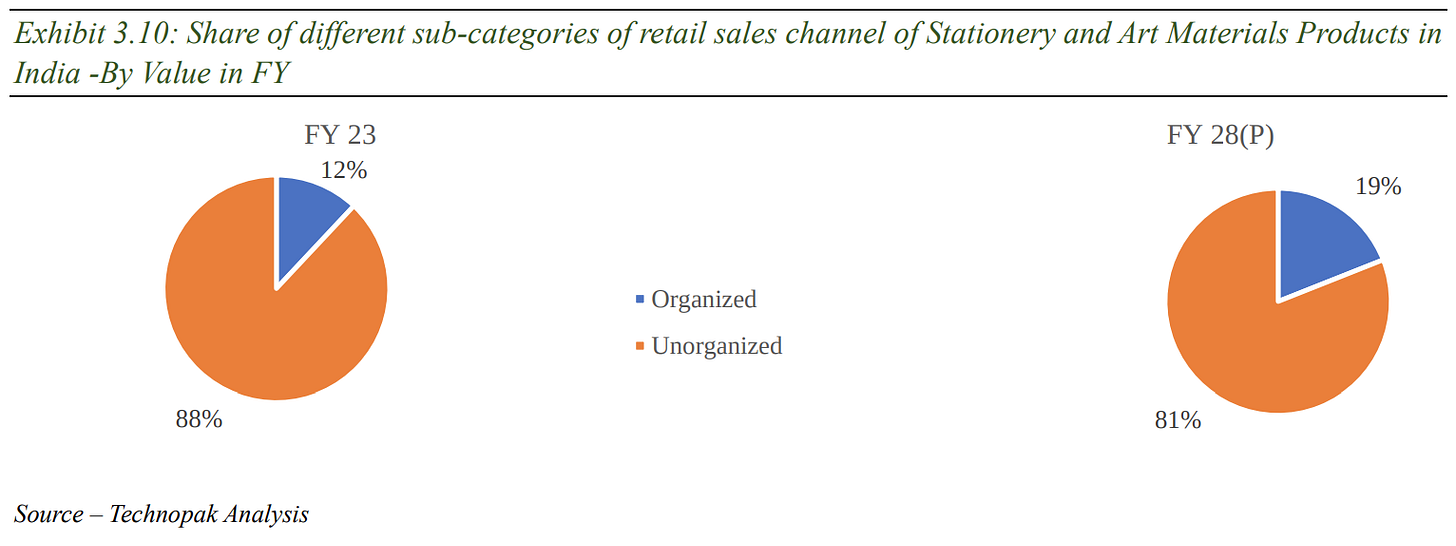

An interesting trend helping the bigger players is the shift from unorganized to organized. Indian consumers are slowly moving towards branded stationery for better quality and reliability, and organized retail is expanding. Organized products made up about 12% of the market by value, and it’s projected to rise to ~19% by FY28. Still not enough, but the trend is solid.

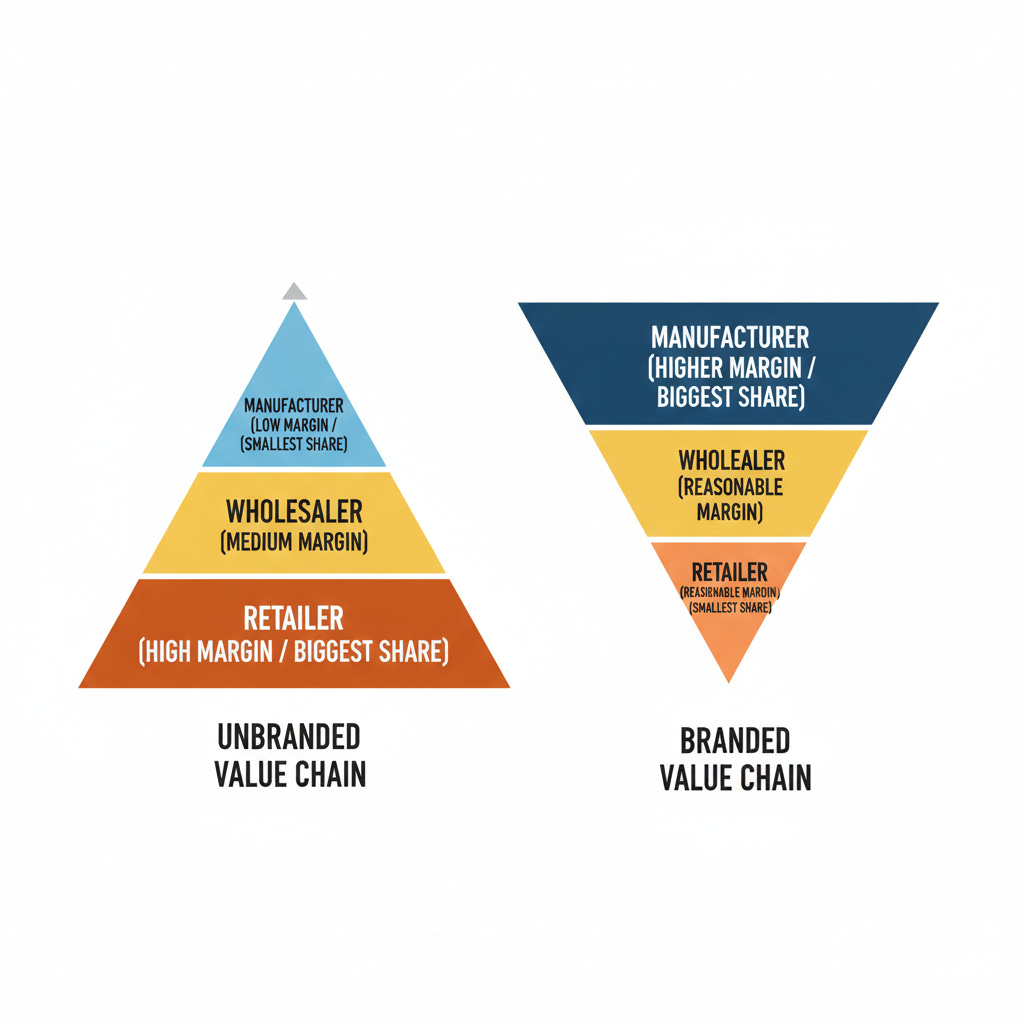

It’s also worth noting how profit pools differ between unorganized and organized players.

In the unorganized value chain, the manufacturer often has to sell cheap (low margin) to wholesalers. However, the retailers mark up a lot — without brand pull, the product only sells if the retailer pushes it, which they’ll only do if their margin is good. So the wholesaler/retailer might enjoy a bigger slice of the profit per item than the actual small manufacturer.

In contrast, branded players capture a higher share of the value. The manufacturer can command a bit more margin thanks to brand appeal, while still giving distributors and retailers a reasonable cut to push their product. The retailer is happy to stock Classmate or DOMS, even at a somewhat lower margin than an unknown brand, because customers want them. Thus, in organized play, the manufacturer’s slice of the pie grows, which is why scaling up can be lucrative if achieved.

The benefits of scaling up become even clearer when you look at raw material costs, which are the single biggest expense in this industry. Whether you’re making pencils, pens or notebooks, you’re dealing with wood, plastic, paper or metal — whose commodity prices can swing wildly on the global market. We’ve seen periods where paper prices shot up due to pulp shortages, or plastic prices rose with oil prices. Such price volatility directly impacts stationery makers — especially unorganized players.

In a price-sensitive market where you can’t raise prices, your margins eventually get squeezed. Branded players usually operate with decent gross margins (often 30-40%), which give some cushion. Smaller unorganized players, with already razor-thin margins, can really suffer during raw material spikes.

Penning down final thoughts

After all this, it’s hard not to smile at the irony: from the user’s perspective, the stationery industry really is a boring business. And that’s exactly why it’s such an interesting one from a business perspective.

In many ways, stationery says so much about India: our education system, our demographics, our slow-but-steady income growth, and our deep-rooted habit of scribbling things down even in a digital world. These drivers aren’t flashy, but they’re dependable. And because of that, stationery may keep recording stable low double-digit annual growth, as it has been so far.

This is an industry where execution and distribution matter far more than innovation or storytelling. If you can build scale, get into lakhs of stores, and consistently show up on that counter where the customer makes the split-second decision — you win. Achieve that, and you suddenly start enjoying better margins, better raw material leverage, and better bargaining power than the thousand small players around you.

Unless you do something spectacularly foolish, it’s hard to go terribly wrong here. People will continue to buy pencils, notebooks, pens, erasers — and students, thankfully, don’t go out of fashion.

How did India’s public-sector oil firms do this quarter?

Globally, at any given point of time, there’s a lot happening with oil. Right now, prices have slumped to multi-year lows because of excess supply. And this is leading to layoffs and capacity reductions across global oil companies. As we covered earlier, between Russian sanctions, tensions in the Middle East, and geopolitical conflict doing very little to stem oil supply, the oil markets are in a weird place right now.

Against this backdrop, India’s oil marketing companies (OMCs) reported their latest quarterly results. It turns out, the same falling crude prices that are hurting India’s largest oil producer have funded a really good quarter for our public-sector refiners. However, our largest OMC, ONGC, recorded a decline in annual profit. Same commodity, same country, same quarter but different outcomes — all depending on where you sit in the value chain.

Let’s dive in.

The numbers

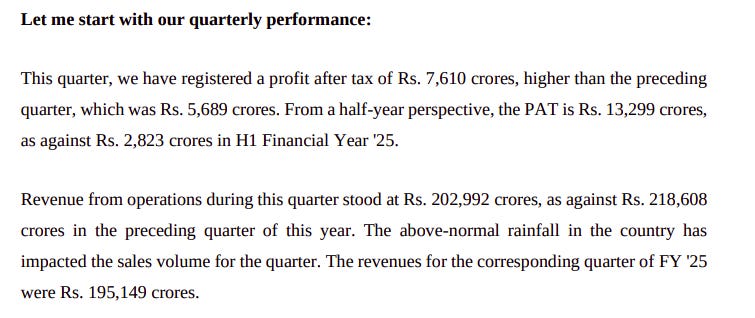

Let’s begin with ONGC, which reported a standalone PAT of ₹9,848 crore in Q2 FY26, down 18% year-on-year. ONGC realized a per-barrel revenue of $67.34, down from $78.33 last year. However, its consolidated PAT rose 28% to ₹12,615 crore.

In particular, there was one subsidiary of ONGC that contributed the most to its consolidated figures. HPCL delivered a quarterly PAT of ₹3,820 crore, versus a mere ₹141 crore a year ago. The profit earned by it in the first half of this year alone already exceeds the full-year profit of FY25.

Moving ahead, there’s IOCL, which posted a quarterly PAT of ₹7,610 crore versus a loss last year. The gross refining margins (or GRM) per barrel — which is what a refinery earns per barrel just from the act of converting crude into petrol hit $10.66, up from $1.59 per barrel a year ago — an increase of nearly 9 times.

BPCL reports its results with a lag of one quarter. So, its standalone PAT of Q1 FY26 was ₹6,124 crore. The GRM was at approximately $4.88 per barrel — these margins are lower than usual, primarily because of excess inventory.

The crude price split

Over the past year, the world has been flooded with oil. That has caused the price of crude to crash from $78 last year to mid-$60s now — the lowest in 4 years. The OPEC+ oligopoly, which controls most of the world’s supply, has been unwinding production cuts, while non-OPEC supply from the US, Brazil and Guyana keeps rising.

For ONGC, this has been painful. Compared to peers, a heavier chunk of their revenues comes from upstream — they pull crude from the ground and sell it. And they incur lots of heavy capex on oil rigs. When crude prices fall, revenue falls too, but the costs stay fixed, leading to shrinking margins. This has been a huge structural disadvantage for them.

For refining-heavy players, though, it’s the opposite. They buy the crude as input and sell finished products. Crude prices falling has optimized their costs. But additionally, despite crude prices falling, Indian retail prices of petrol have remained unchanged since March 2024. This has expanded their margins from both sides.

Why did Indian retail prices not fall? Well, for one, the government is allowing them to earn these profits — HPCL openly admits this in their earnings call. Partly, this is a reward for heavy capex done recently. But partly, perhaps, this is also a reward for when, in FY24, crude prices climbed up, and OMCs were forced to hold retail prices constant and eat the losses.

However, another reason could be that while cheaper crude increases refining margins, they do increase losses for the upstream side that keeps inventory. This is the dilemma that ONGC, for instance, faces.

The LPG burden

Together, HPCL, IOCL and BPCL supply the cooking gas needs of nearly every kitchen in India. Every few weeks, a delivery person shows up at their door with a 14.2 kg cylinder, which is priced at ₹803-850 depending on the city. The government has made LPG an essential public good, and households must get cheap, subsidized prices even if that means OMCs have to bear some financial losses.

On that note, LPG prices haven’t moved in a while. But the cost of supplying it has.

Now, as we covered earlier, we don’t produce enough LPG domestically. A large chunk is imported from Saudi Aramco. When global prices rise, the government always expects refiners to absorb the loss rather than pass it to households.

By mid-2025, though, that pain had accumulated. IOCL’s negative buffer crossed ₹26,000 crore, while BPCL’s hit ₹12,523 crore. Think of the buffer as a running tab – every cylinder sold below cost adds to it. A negative buffer of ₹26,000 crore means IOCL has absorbed that much in LPG losses over time, waiting for the government to settle up. At peak, companies were losing ₹100-150 on every cylinder sold.

So, in August, the government decided to ease the buffer of each OMC: IOCL will get ₹14,486 crore, while HPCL gets ₹7,920 crore, and BPCL ₹7,500 crore, disbursed monthly starting November.

But, the real relief came from the market, as Saudi Aramco’s prices softened. At the same time, OMCs have reworked how they procure crude, while not exactly detailing the specifics of how.

All of this has certainly helped the numbers. BPCL’s loss per gas cylinder dropped from ₹150 in Q1 of this year to ₹30 by September. Similarly, IOCL went from ₹100 to ₹40. Households continue to have their gas subsidized, but the cost to refiners has become more manageable.

The capex cycle accelerates

India is the single largest contributor to global oil demand growth, with consumption rising faster than any other major economy. But, for the longest time, OMCs didn’t really get to refine this oil and simply sold it, missing out on the potential refining margins. Now, they’re racing to capture those profits by investing heavily in capex.

HPCL, for instance, just completed upgrades to its Vizag plant. This is expected to add around ₹2,500-3,000 crore to the yearly EBITDA. They’ve also nearly completed building their refinery in Barmer, Rajasthan — and target crude-in by March. Once both stabilize, their refining capacity could match their sales volume for the first time.

Meanwhile, IOCL is spending ~₹33,500 crore on capex needs in FY26. The upgrades to their Panipat refinery, for instance, should add 10 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) worth of refining capacity by June 2026.

BPCL is spending a whopping ₹20,000 crore this year, and hopes to scale to ₹35,000 crore by FY28-29. Moreover, they’re mostly funding their capex needs with cash instead of debt.

ONGC, of course, is more focused on upstream rather than refining capacity. It is spending ₹30,000-35,000 crore annually on exploration projects.

The Mozambique wildcard

India has also doubled down on exploration of gas fields outside of our borders. Some time ago, our OMCs decided to bet billions on mining a new gas field they discovered 7,000 kilometers away — in Mozambique.

Mozambique is a small country on the southeastern coast of Africa. It sits on one of the largest natural gas discoveries found in recent times. Their offshore Rovuma Basin, for instance, holds ~180 trillion cubic feet of gas — enough to supply India’s current consumption for over 80 years. That’s incredibly valuable.

The Area 1 LNG project in Mozambique, for instance, was supposed to change India’s energy equation. It promised 12.88 MTPA of liquefaction capacity, meaning decades of supply locked in. OVL alone invested $6.6 billion. Then in March 2021, an insurgent attack in the country halted all activity for a good four years.

However, this quarter, the situation seems to have changed. All three Indian partners — ONGC, BPCL, and Oil India — are optimistic about finally restarting exploration activity in Area 1 soon. This has no bearing on the Q2 results, but it could be extremely important going into the future.

Private competition heats up

Of course, PSU refiners aren’t operating in a vacuum. Private players like Reliance and Nayara are competing aggressively. And they’re not bound by the same social, public-good aims that PSUs are inherently subject to.

For instance, take the throughput-per-outlet metric. When asked why private players show better per-outlet numbers, BPCL’s management said that their mandate is to cover every inch of India, no matter how much it costs to do so. Private players, meanwhile, are free to focus on the highest-selling areas which tend to be more urban. This automatically gives them higher margins, which also allows them to pass on some discounts to consumers.

For the most part, PSU refiners are avoiding price wars. BPCL, for instance, has said that they’ve been unwilling to discount high-speed diesel (HSD) prices in response to private firms. However, because of that, their retail HSD market share slipped slightly this quarter.

But, instead of price wars, PSU refiners have been trying to become more efficient in other ways to compete better. For example, BPCL is running an AI-enabled platform called IRIS to remotely manage their retail outlet operations. Their QR-based payment system processes 6 lakh transactions worth ₹30 crore daily across 15,000 outlets. HPCL, meanwhile, is running a retail outlet efficiency program, which, while not meeting targets, has beaten industry averages which have either been flat or negative.

The bottom line

The current setup has been quite favorable for India’s oil PSUs. Refiners, of course, have benefited the most out of the setup. With further capacity additions, they hope to add to their margins by the next 2-3 years. However, for players operating upstream, the setup was not as helpful. While volumes were healthy for ONGC, realizations per barrel have declined significantly.

Policy helps prop up this setup. By providing stable retail prices despite lower crude costs, the government has given a huge boost to the profits of refiners, and are also willing to compensate LPG losses.

OMCs are also expanding their ambitions to fuel India’s growing energy demand by investing in capex. This also includes upstream, where all of the major public-sector OMCs are looking to drill new gas fields, especially in Mozambique.

Now, oil markets can be incredibly volatile. Oversupply today can immediately swing into a shortage later. The trick, as always, is to manage the rough cycles this commodity goes through. Indian OMCs, it seems, know this all too well.

Tidbits

Tata Consumer in talks to buy Danone India’s nutrition portfolio

Tata Consumer is in advanced talks to acquire Danone India’s nutraceuticals and specialised nutrition brands, including Protinex, Farex and Dexolac. The deal would push Tata deeper into the booming protein and wellness market. Valuation talks are close, but analysts warn infant nutrition is heavily regulated and dominated by Nestlé and Abbott.

Source: Economic Times

Russia’s Sberbank launches Nifty50-linked mutual fund

Sberbank has launched ‘First–India’, a Nifty50-linked mutual fund that lets Russian retail investors gain direct exposure to India’s largest companies. Announced during CEO Herman Gref’s India visit, the fund strengthens India–Russia financial ties and fills a long-standing gap for Russians seeking access to Indian equities.

Source: Business Today

Jindal says subsidies key to Thyssenkrupp steel bid

Jindal Steel International said European subsidies will be “an important factor” in deciding whether to take over Thyssenkrupp’s steel division, Germany’s largest steelmaker. Jindal is conducting due diligence after submitting an indicative bid and says moving to green steel makes long-term economic sense.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Samdarsh.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Recently started reading, kept me hooked till the oil markets ,it was interesting but then I lost it ( attention span🤌)

But good work,

The stationery part brought back so many memories and it also made me realize how strong this industry actually is. It’s crazy how simple products can have such interesting business stories behind them.