Why Sun Pharma Is Betting on New Drugs

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Pharmaceuticals I: The Sun King

India's oil sector results

Pharmaceuticals I: The Sun King

For most people, the word pharma brings to mind doctors, pills, prescriptions, and perhaps white-coated labs.

Maybe that is the case. But behind this is one of the most complex, globally-entangled industries we’ve come across. Trust us, it’s a lot. It’s a space where science meets law, where pricing power meets public health, and where decades of investment can collapse — or explode — with a single regulatory call.

India sits at the heart of it all: we’re not just a low-cost manufacturing base, but increasingly, a powerhouse of chemistry, compliance, and business innovation.

It took us ages to get any sense of the sector, and we’re still not sure we have much of a command on it. But we’re going to run through two major pharma companies to understand how they work, and how they did last quarter. We’ll do this in two parts — today, we’ll look at India’s reigning generics giant, Sun Pharma. One of these days, we’ll return to look at India’s contract drug manufacturing industry.

Understanding the pharma sector

Before we dive into the results themselves, let’s give you a basic framework to understand the sector.

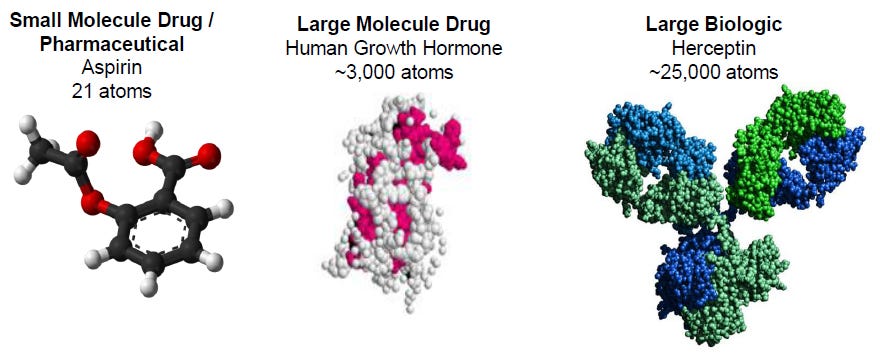

Pharmaceuticals are broadly split into two camps — small molecules and large molecules. This classification is literally a matter of the number of atoms in your medicine.

Small molecules are your standard chemical drugs — something like a paracetamol. They’re made through a series of chemical reactions, batch after batch, in reactors. These medicines usually dominate pharmacy shelves, and make up most of what India exports.

On the other side are large molecules, or biologics — insulin, antibodies, vaccines, and the like. These are many orders of magnitude more complex. Standard lab procedures don’t work at this scale. These are often made using living cells, have to be stored in perfect conditions, and are mostly injected.

As you might imagine, the requirements of the two are so different that they’re practically two different industries. India’s global edge was built on small molecules. But we are now learning how to compete in biologics too.

India and pharmaceuticals

How did India become so good at making medicines? The answer lies deep in our patent law.

See, patents usually protect the rights of inventors over their inventions. In the pharma business, this means a pharma company has a complete monopoly over any new drug it discovers for a while — usually twenty years.

That wasn’t a system we were too comfortable with. Back in 1970, India rewrote its rules and scrapped product patents for pharmaceuticals. That meant no one could own a drug — only the process to make it. If someone figured out a new way to make the same medicine, they could sell it. Every medicine, in a sense, became a chemistry puzzle to solve. And Indian chemists became world-class at cracking them. This set off an entire wave of medical reverse engineering. Companies like Cipla and Ranbaxy (now part of Sun Pharma) built their fortunes selling cheaper versions of blockbuster western drugs.

This model worked so well that when India joined the WTO in 1995, and agreed to comply with TRIPS — a global intellectual property agreement — we negotiated a full 10-year transition period to bring back product patents.

But even once we brought back product patents, we tried to make sure we weren’t returning to pharmaceutical monopolies. In 2005, the Indian Patents Act was amended again to bring back full patent protection, but with one massive guardrail — Section 3(d).

Section 3(d) is simple in principle, but powerful in effect. It blocks patents on new forms of known substances unless they show a significant improvement in therapeutic efficacy. This single clause has shaped India’s pharmaceutical landscape more than any other. It stops companies from ‘evergreening’ their drugs — making minor tweaks and getting a new patent, extending their monopoly for an extra twenty years.

For instance, this prevented Novartis from patenting the beta-crystalline form of Glivec — allowing Indian companies to sell it for ₹8,000-10,000, instead of the ~₹1.2 lakh that Novartis charged. Novartis challenged the law, going all the way to the Supreme Court. They lost.

To further protect access, India also retained its right to issue ‘compulsory licenses’. This means that if a drug is too expensive or not available in sufficient quantities, the government can allow someone else to make it.

That’s what happened in 2012, when Natco got a license to make a generic version of Bayer’s cancer drug Nexavar. Bayer was selling the drug at nearly ₹2.8 lakh per month. Natco slashed the price down to ₹8,800. Bayer fought it in court — and lost. The ruling set a global precedent. Even though compulsory licenses are rare, the mere threat of one often forces companies to price more responsibly in India.

This patent architecture gave rise to an entire ecosystem of generic drug makers. India became the world’s largest provider of generics — accounting for 20% of global supply by volume.

But it didn’t stop there. Over time, Indian companies started moving up the value chain — from simple oral tablets to complex injectables, and from copying drugs to modifying them, eventually to developing their own. Slowly, they began building a global reputation for quality.

The pharma value chain

Pharmaceuticals aren’t just about the molecules. The challenge is to make them at scale, to global standards, at the right price.

Which brings us to the value chain.

At the very top of the chain is discovery. This is where new drugs are born. And it’s long, expensive, and full of disappointment. Companies routinely sink in billions of dollars over decades, chasing a success rate of less than 1 in 10,000 compounds. This is why pharma companies are so aggressive with patenting anything they discover. Not many Indian firms play here — and even if they do, they aren’t at the top of the game.

If a molecule looks promising, it enters preclinical, and then clinical trials — where they’re tested on real people. India has a growing presence in clinical trials, especially for global pharma. That’s a little depressing, to tell you the truth — we’re just a cheaper location to test drugs on people, and we have a large and diverse patient pool. Plus, we’re familiar with global protocols. Contract research organizations or CROS help run these trials. They recruit patients, collect data, and coordinate with regulators.

Then comes ‘API manufacturing’ — the backbone of any drug.

API stands for ‘Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient’ — that part of the drug that actually works. India is one of the world’s largest API producers. But there’s a catch: for many APIs, India still depends on China (yes, that again) for key starting materials (KSMs) and chemical intermediates. About 70% of India’s bulk drug imports come from China. This is a major risk, and one that came into sharp focus during COVID. The Indian government has since rolled out incentive schemes to boost local production and reduce this dependency.

After APIs come formulations — where these ingredients are turned into pills or vials. This is where companies like Sun Pharma, Cipla, and Dr Reddy’s dominate. They run massive plants; some making tablets, others producing sterile injectables, some specialising in inhalers or eye drops.

Many of these facilities are FDA- and EMA-approved, and that’s a big moat: it’s a license to export to the US and Europe. Compliance is key in this part of the business. One failed inspection can shut down a plant. That’s why pharma companies obsess over data integrity, batch records, and electronic audit trails. Indian firms have faced setbacks here in the past, but overall, compliance has improved significantly.

Finally, once a drug is manufactured, it needs to be packaged, branded, and shipped.

In the Indian market, most drugs are sold as branded generics — that is, different companies sell the same molecule under different brand names. This is a murky area, with deep competition. Doctors still prescribe by brand, not by the chemical it contains. And this is why companies compete for their mindshare through large teams of medical representatives. This race is unique to India; abroad, the same companies compete on price alone.

Distribution is a beast in itself. There are over 12,000 stockists and 250,000 pharmacies in India. And increasingly, e-pharmacies like 1mg and NetMeds are making their own forays. Cold-chain logistics are needed for biologics. Warehousing, inventory management, and regulatory labeling are all tightly controlled.

There’s more we’re yet to explore. In a coming episode, for instance, we’ll dive deep into the newly emerging contract manufacturing space. But for now, let’s look at one of India’s biggest drug manufacturers: Sun Pharma.

Sun Pharma

If you ever walk into a pharmacy in India, there’s a decent chance the drug you’re holding came from Sun Pharma. They're not just some pharma player — they’re the largest pharmaceutical company in India, and one of the top four generic drug makers in the world.

But, right now, if anything, they’re actively trying to break out of that very category.

Breaking out of generics

Sun made its name by selling generics — copycat versions of branded drugs, once patents expire. Generics companies prosper by making these old drugs for cheap, and then selling them at scale. But if you’re making a copycat product, there’s nothing setting you apart from others that are doing the same. And so, the generics industry is brutally competitive. Prices keep falling, and margins are thin.

That’s why, over the past few years, Sun’s quietly been repositioning itself — away from generics, and towards something much more lucrative: specialty drugs.

These are complex formulations — biologics, injectables, dermatology or cancer drugs — that treat chronic or severe illnesses. These are complicated to make, but if you can crack it, you often face less competition. Relative to other pharma products, specialty drugs behave like a premium industry: it’s harder to enter, costlier to scale, but more defensible and sticky once you’re in.

How’s that strategy playing out? Well, that’s where these Q4 FY25 results get interesting.

Sun Pharma clocked consolidated revenue of ₹12,816 crore for the quarter — a tame growth of 8.5% year-on-year. But a lot more of that revenue translated into earnings. The company’s EBITDA rose sharply by 22.4% to ₹3,716 crore, with margins expanding to 28.7% — one of the highest margins they’ve posted in recent quarters.

Their final bottom-line was less impressive. Adjusted net profit (excluding one-offs) came in at ₹2,889 crore, up 4.8% YoY. And reported PAT fell to ₹2,149 crore, due to a ₹2,597 crore impairment on their investment in Lindra Therapeutics.

That PAT dip shouldn’t trouble you too much about their core operations. It came from one-time accounting hit, not a business miss.

Now, break that ₹12,816 crore revenue figure across geographies and business lines, and you’ll see exactly how the business is structured. One-third of its business comes from India. Another third comes from the United States. The rest of their business is split among the rest of the world, and its small API-manufacturing vertical.

With that, let’s look at how each part of the business is behaving.

The India business is a fortress

Let’s start at home. Sun is the #1 player in India, both in market share and in prescriptions.

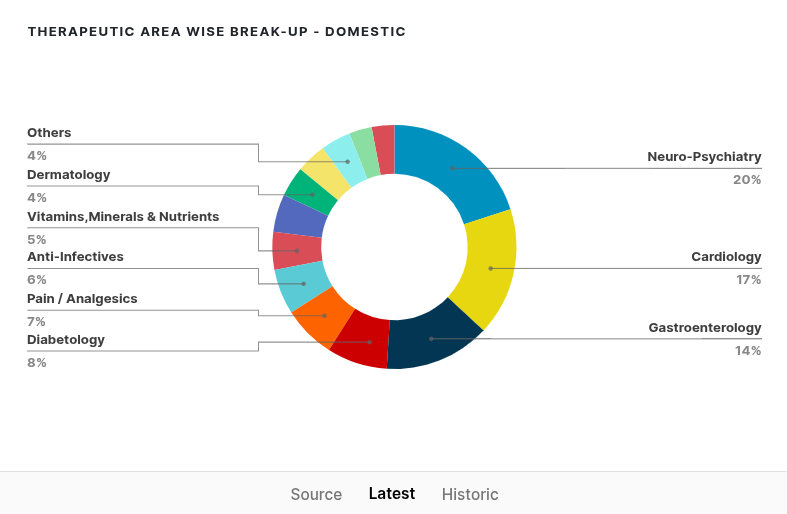

Its domestic formulation business grew 13.6% YoY in Q4, comfortably ahead of the broader Indian Pharmaceutical Market (IPM). It now commands 8.3% market share, up from 8.0% last year. This growth is largely volume-led; it doesn’t come from price hikes. That’s crucial. It means doctors trust the brand, and patients stick to it.

But this success isn’t just a matter of scale — it’s one of depth. Sun dominates across therapy areas: cardiology, dermatology, CNS, gastro, and diabetes. In fact, it’s the most prescribed brand in India across 13 different categories. Whatever your ailment, it seems, Sun has something for you. This quarter alone, in fact, the company launched 10 new products.

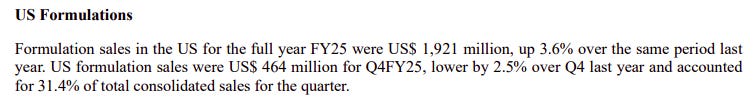

The US generics business is under pressure — but that’s old news

Sun’s US business has long been the crown jewel of its international presence. But in Q4 FY25, US formulation sales declined 2.5% YoY. That’s not a catastrophic fall, but it’s not trivial either — especially when the rest of the business is growing.

The issue? The generic part of the US business, which still makes up a good chunk of the US revenue, is taking hits on three fronts:

Price Erosion: This is the biggest structural challenge across the US generics industry. When a drug goes off-patent in the US, multiple players rush in. That competition leads to a collapse in prices — often by over 90% within the first year of generic entry.

Over time, this erosion can continue, especially if the drug is easy to make. Sun management acknowledged this in the earnings call:

“Price erosion pressure remains on a product-to-product basis.”

Translation: while not all generics are suffering, many are — and the ones that are, are declining fast.

Increased Competition: In Q4 specifically, Sun said the generics business declined “due to additional competition in certain products.” We’re not sure what, precisely, happened, but there are two possibilities. One, Sun may have taken a big hit on some specific drug, facing a ‘Loss of exclusivity’ (LOE): basically, there was a 180-day exclusivity period where it was the only one making a newly launched generic, but that expired. The other possibility is broader: there were just more firms launching competing generics against existing Sun products. The company itself didn’t point to the specifics, but this is common in the US. It’s simply a hugely competitive market.

Product-Specific Weakness: Sun emphasized that the challenges weren’t broad-based across the entire portfolio. They said:

“The pressure is product specific... nothing that indicates a structural worsening across the whole industry.”

So there’s real damage, but it’s not systemic. Some molecules are just past their peak. And no, this isn’t just because the patent over the blockbuster cancer drug, Revlimid, has come to and end. Management confirmed that this was not a big swing factor this quarter. Management confirmed:

“Revlimid sales in Q4 were similar to Q3 and not a significant contributor.”

The specialty pivot is real—and it's working

With such intense competition for making generic drugs, Sun’s looking at specialty products as a way out. These now account for nearly 20% of Sun’s global revenue. That’s up from ~15% just a few years ago.

This is a new kind of business altogether. Sun’s moving away from tiny molecules — it now has blockbuster ambitions. Its flagship specialty drug is Ilumya, used to treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, an autoimmune disease that causes the one’s immune system to mistakenly attack healthy skin cells, giving people thick, scaly patches of skin. Full-year sales for the drug were up 17% YoY.

But two other names are about to join the party:

Leqselvi: This is an oral therapy for alopecia areata, a condition that causes hair loss. The USFDA has approved the drug, and it’ll be launched some time in Q2 FY26.

Unloxcyt: This is a drug for skin cancer. This has been approved as well, and its launch is planned for FY26.

Together, these could give Sun Pharma its next wave of growth. The company’s investing $100 million just to commercialise these two molecules alone in the US this year. More might soon follow. Sun’s R&D pipeline includes eight novel specialty molecules in clinical trials, and dozens more just behind.

In fact, about 36% of the company’s entire R&D spend this quarter was for specialty. Something is clearly brewing.

India's oil sector results

India's energy sector — like most others — can be broadly split into two major segments.

First, there's the stuff that we’re digging out of the ground — coal, petroleum and natural gas — which fuels vehicles, moves goods and heat homes, apart from being critical ingredients in products ranging from plastics to medicines. Then, there’s an entire industry built around turning that into electricity, our most usable form of energy, and then bringing it into our homes and industries.

Every single link in this chain is an absolute behemoth. There’s so much to dig into that we couldn’t say anything intelligible about the entire sector even if we tried. And so, we're keeping things simple. We’ll focus entirely on a small set of companies that all, broadly, work with petroleum (and a little natural gas).

Petroleum companies, alone, operate across a long chain of activities. At one end, "upstream" companies like ONGC explore the earth for oil and gas reserves. They drill wells and bring crude oil and natural gas out from deep beneath the surface. At the other end, "downstream" companies like Indian Oil (IOCL) and Hindustan Petroleum (HPCL) take this crude oil and refine it into fuels we use daily — petrol for your car, diesel for trucks, jet fuel for airplanes, and many other products. These refined products eventually reach consumers through your local gas stations and other retail outlets.

There’s also a lot happening in between — the “midstream“ work of processing, storing, and moving that petroleum and natural gas around. We’ll get to that some other day.

Now, this sector deals in “commodities” — with standardised products that all compete without differentiation. And that means it's highly sensitive to global market forces. Oil prices swing up and down based on a mix of factors: global supply-demand dynamics, geopolitical conflicts, unusual weather conditions, and broader economic trends.

Recently, India's biggest petroleum companies released their quarterly results, and these numbers reveal something notable—when oil prices shift dramatically, not everyone in the oil sector feels the same impact. If anything, our current scenario can be neatly summed up as "upstream pain, downstream gain."

The context: Declining oil prices

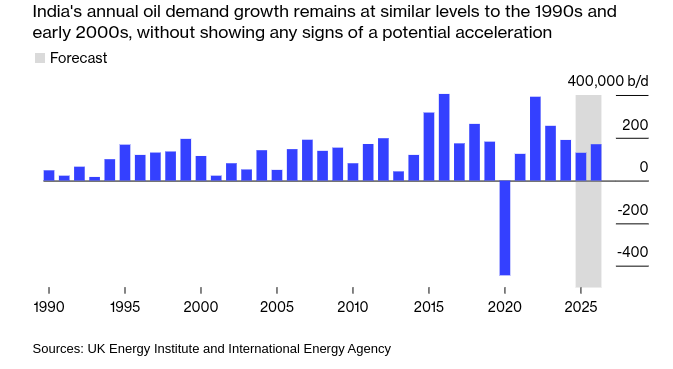

Crude oil prices have been falling for many months all over the world. It’s down from peaks of over $110 per barrel in 2022, to around $60-70 per barrel today. In fact, for a brief while, it even dipped below $60 a few days back!

This decline is due to several reasons. There are some fundamentals: slower growth in countries like China, increased production flooding in from America, and uncertainty about future demand for oil in view of the green energy transition. And beyond that, the OPEC+ is up to all sorts of games, as we’ve discussed before.

Just look at India. Our demand for oil has contracted for the last three months, and it’s expected to remain muted in the future as well. There’s no expected boom on the horizon.

But that’s a whole other story on its own for another time.

But more immediately, here’s something interesting: this oil price decline created a divergence between those upstream and downstream in the PNG value chain. When prices fell, anyone in the business of drilling down and selling oil saw their revenues drop. Every dollar decline in overall oil prices, after all, translates to lower revenues for each barrel they produce.

But on the other hand, downstream companies — who buy crude oil to process and refine it — can actually benefit from lower input costs. If there’s a gap between when crude costs fall, and their refined output does, that cushions their margins.

This is what we saw in the Q4 2025 results of India's major oil companies.

ONGC

ONGC's Q4 2025 results were a horror show. Its performance, this quarter, reflected the challenges of an upstream company in a time of declining oil prices. The company was still profitable — it reported a profit of ₹35,610 crores for the full year. But that was 12% lower than its ₹40,526 crore profit the previous year.

How do we know that this reduction was primarily because of oil prices? Because ONGC's oil production actually increased year-over-year. The company's standalone crude oil production increased by 0.9% over the previous year, reaching 18.558 million metric tons. And yet, revenues fell.

Now, that shouldn’t convey a static picture of the company. There’s a lot happening behind the hard numbers.

For one, the company is making major investments into expanding its capacity. ONGC spent a record ₹62,000 crores on capital projects in FY 2024-25. About ₹38,000 crores went to their traditional oil and gas business. It’s betting that these investments will lead to more oil and gas production in the coming years.

Two, the company is trying to get more out of its existing oil fields. ONGC achieved a significant operational milestone last year, when it reversed the typical production decline you see in aging fields. Usually, as oil fields get older, they naturally produce less oil. But ONGC reversed that, by drilling more wells into the same fields. It’s like it got more juice from the same oranges through better squeezing techniques. This helped ONGC maintain a ‘reserve replacement ratio’ above 1 for the 19th consecutive year — that is, they've discovered more new oil and gas reserves than they've extracted yet again.

Three, the company is diversifying heavily from oil: on the one hand, it’s trying to expand into renewable energy. On the other, it’s trying to move into a wider range of chemicals.

In the short term, though, global conditions have put the company in a tough spot.

Another reason for profits falling — a pretty major one — was ONGC’s ₹7,480 crore write-off for exploratory wells. A write-off happens when a company decides that money it has already spent — in this case, on drilling new wells — is unlikely to generate any future value. And so, it records that amount as a loss in its financial statements. These new wells might have made sense when oil prices were high, but now they no longer seem worth developing.

Here’s what the Chairman and CEO Arun Kumar Singh said about this:

"If you look at our performance, it can be classified as pathetic in three categories. One is our conventional E&P [Exploration & Production] business … basically, our PAT going down by 12% if you single the only reason, you can say is that out of 4,000 some odd crore — 4,200 — is on account of exploratory well write-offs. Exploration in our business is something like investment. Unless you explore, you don't find new finds and unless you get new finds, your future is not assured. So you would notice that this year we have accelerated our exploration on both sides. So capital expenditure itself is now 25% up and naturally we had some discovery, we had some dry wells too. So basically if you discount this write-offs, then our profit is at the same level, PAT is at same level."

IOCL and HPCL

While ONGC struggled, though, downstream refiners like IOCL and HPCL had a relatively better quarter.

IOCL reported a revenue of ₹8,45,513 crores for the full year — down slightly from ₹8,66,345 crores in the previous year. But while the year may have been disappointing, it ended on a high. Last quarter, its net profit was ₹7,264.85 crores, a whopping 50% jump from the same period last year.

HPCL's business performed well too. It saw an 18% increase in quarterly profits, to Rs. 3,355 crores. The company reported a revenue from operations of ₹1.18 lakh crores — slightly shy of its ₹1.22 lakh crore last year.

But both their stories are nuanced. We’ll go through each aspect, bit by bit.

Refining Margins

The refining business operates on what's called the "crack spread" – the difference between the cost of crude oil inputs and the prices of refined products like gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. The higher this margin is, the better the profits.

Indian Oil Corporation (IOCL) saw a dramatic improvement in its refining margins during the quarter. It earned a Gross Refining Margin (GRM) of $7.85 per barrel in Q4, way above $2.95 per barrel in the previous quarter. Given the sheer number of barrels it produces, that number adds up. A ~$5 per barrel improvement in margins translates to roughly $2.5 billion in additional gross profit.

This reversed the trend it had seen over the rest of the year. Zooming out, the company’s full-year normalized GRM fell to $4.53 per barrel, from $11.44 per barrel in the previous fiscal year.

HPCL saw similar patterns. Its GRM for the quarter was $8.44 per barrel — better than $6.95 per barrel in Q4 FY24. But over the full year, the normalized GRM for FY25 was $5.74 per barrel, down from $9.08 in FY24.

This decrease in the full year GRMs points to a larger challenge the refining industry faced for much of the year. Volatile crude prices, combined with weaker product demand, meant that their margins had been squeezed for most of the year. Essentially, even though their input costs came down when oil prices fell, they had to pass most of that on to their clients. Because their own demand was much lower, they couldn’t hold on to any of it as profit.

But the sharp turnaround in Q4 tells us how fast refining economics can change.

Volume and Utilization Effects

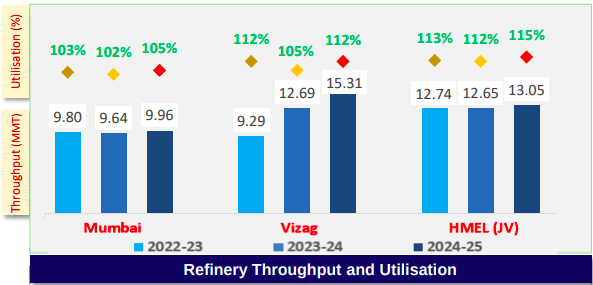

Both IOCL and HPCL processed more crude oil than ever before last quarter. This ‘volume effect’, too, also pushed up both companies’ profits.

IOCL achieved its highest-ever sales volume of 100.29 million metric tons during the year, crossing the 100 MMT milestone for the first time. Its refinery throughput reached 70.5 MMT. Its capacity utilization exceeded 100%, in fact — essentially, its refineries were pushed beyond their maximum capacity.

HPCL, too, achieved record refining throughput of 25.27 million tons. Its quarterly capacity utilization crossed 100% too — reaching 107.1% in Q4.

You can only get to such high utilisation rates if you’re producing in overdrive; if you’re doing something — working extra shifts, cutting down bottlenecks, or pushing your machines hard — to go beyond the supposed limits of your unit. And that can do a lot for a refiner. This is a business with significant fixed costs — you’re paying a lot to lease land, maintain your facilities and sustain your workforce, and those costs remain constant regardless of production levels.

If you produce more, you spread these costs across more barrels, making each individual barrel less costly. And that boosts overall earnings.

Marketing Margins

IOCL and HPCL are also in the oil marketing business — selling refined products to consumers and businesses. They make ‘marketing margins’ here, which is the difference between the price refiners pay for products, and the price at which they sell to end customers.

IOCL described its marketing margins as "positive", with non-fuel products like lubricants and specialty chemicals performing particularly well. The company's massive retail network, with over 40,000 stations, meant that these margin improvements count for a lot.

HPCL's marketing performance was even stronger. Its domestic sales growing 5.5%, compared to the industry’s overall 4.2% growth.

Inventory Gains

The most interesting facet of this business, last quarter, was inventory gains.

Inventory gains don’t come from operations, but from accounting. The value of a company’s inventory changes as prices move – they’re marked to the market every quarter. These gains or losses show up on the books even before the products are actually sold, which can make a company’s earnings look better or worse than the underlying operations would suggest.

IOCL reported inventory gains of approximately ₹600 crores on the refining side and ₹550 crores on the marketing side during Q4. These gains, totaling over ₹1,100 crores, represented a substantial boost to quarterly profits. Over for the full year, though, the company saw net inventory losses.

HPCL experienced something similar. Q4’s inventory gains helped it offset losses from earlier periods.

This adds a layer of complexity to their results. Price volatility outside the company can change how its results look, even if its operations are exactly the same.

Other segments

All in all, this was a decent quarter for the downstream oil business. But that’s not all these companies do. And elsewhere, the picture is more murky.

These companies are also in the petrochemicals segment. And there, things are more complex — global uncertainty killed demand in major markets like China and Europe, even as new facilities across Asia and the Middle East flooded the market with supply. As a result, chemical prices fell even more than the price of crude oil. And with that, the chemicals business became unprofitable.

IOCL noted this as a key issue. But thinks this is just temporary, with a cyclical downturn at play:

The same problem pops up when you contrast HPCL's standalone and consolidated results. The 18% increase in profit that we spoke about earlier was just HPCL's standalone results — where they house their core operations. However, when you include its subsidiaries and joint ventures, its consolidated profits fell by 25%.

One of the primary victims was HMEL (HPCL Mittal Energy Limited), an HPCL joint venture that has major petrochemical operations. Apart from fuel, HMEL also produces a lot of chemicals and plastics from crude oil. And this became a liability rather than an asset during Q4 2025.

Both companies also faced significant challenges from India's LPG subsidy policy.

See, India's LPG subsidy system requires oil marketing companies to sell cooking gas cylinders to domestic consumers at fixed prices, typically below market rates. The government then reimburses companies for this difference, known as "under-recovery."

But there’s a problem: these reimbursements don’t always come on time. In the interim, these companies must stomach the loss. IOCL absorbed ₹20,000 crores in LPG under-recoveries during the full year, while HPCL faced ₹10,900 crores in similar losses.

This burden hit HPCL particularly hard, due to its business structure. Domestic LPG sales account for approximately 90% of the company's total LPG business, which means they took a hit on almost all their cooking gas sales. Commercial and industrial LPG sales, where companies can charge market-based prices, makes for only 10% of their LPG portfolio. Which is why, at the moment, HPCL’s LPG business is a massive drag on its profitability.

The government did take some action during the year, increasing LPG prices by ₹50 per cylinder, which reduced the per-unit under-recovery. However, that only went so far in bailing these companies out.

Conclusion

The Q4 FY2025 results for India’s oil sector were a study in contrast.

Upstream players like ONGC found themselves squeezed by falling oil prices. On the other hand, downstream refiners like IOCL and HPCL enjoyed better refining margins, and their record throughput led them to deliver good profits.

But how this will continue isn’t clear. This business is hostage to changes in oil markets all across the world. Verticals like petrochemicals are facing both structural and cyclical pressures. LPG subsidies add long-term question marks on the business. Through all this, operational excellence can only drive these companies so far. In the long term, it’s events happening outside these companies that will determine their future trajectory.

Tidbits

BSNL Posts Back-to-Back Profits in FY25, Records Highest-Ever Revenue and Ebitda

Source: Business Standard PIB

State-run BSNL has reported a net profit of ₹280 crore in Q4 FY25, marking its second consecutive profitable quarter for the first time since inception. This follows a ₹262 crore profit in Q3 FY25 and contrasts sharply with the ₹849 crore loss in Q4 FY24. For the full year, BSNL narrowed its net loss to ₹2,247 crore, down 58% from ₹5,370 crore in FY24. Operating revenue rose 7.8% to ₹20,841 crore, while total income stood at ₹23,427 crore, up 10% year-on-year. Ebitda more than doubled to ₹5,396 crore from ₹2,164 crore a year earlier. Revenue from mobility services increased 6% to ₹7,499 crore, and FTTH revenue grew 10% to ₹2,923 crore.

BAT Trims ITC Stake by 2.3% in ₹11,613 Crore Block Deal

Source: Deccan Herald

British American Tobacco (BAT) Plc has offloaded a 2.3% stake in ITC Ltd for ₹11,613 crore through a block deal executed via its subsidiary, Tobacco Manufacturers (India) Ltd. The transaction involved the sale of 29 crore shares at a floor price of ₹400 per share, representing a 7.8% discount to ITC’s previous NSE closing price of ₹433.90. Following the sale, BAT’s stake in ITC has reduced from 25.44% to 23.1%. The sale was executed through multiple tranches on the NSE and BSE under the bulk sale route and is entirely secondary in nature, with ITC receiving no proceeds. Goldman Sachs India and Citigroup Global Markets India acted as placement agents. BAT has imposed a six-month lock-up period post-transaction, restricting further divestment during this time. The company stated the move will enhance financial flexibility while continuing to view ITC as a core strategic asset.

CPCL Gets Nod for Fuel Retailing, Eyes Direct Market Play

Source: Business Line

Chennai Petroleum Corporation Ltd (CPCL), a subsidiary of Indian Oil Corporation, has received approval from the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas to begin retailing petrol and diesel through its own outlets. CPCL currently operates a 10.5 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) refinery at Manali in North Chennai, which supplies products such as petrol, diesel, and LPG exclusively to IOC. The company has now announced plans to enter the competitive retail fuel market, which includes PSU giants like IOC, BPCL, HPCL, and private players like Reliance, Shell, and Nayara. While CPCL has not yet disclosed the number or location of planned outlets, the move marks a significant shift from being a backend refiner to a direct-to-consumer marketer. This follows a precedent set by MRPL, a division of ONGC, which began retail operations in 2005 and now has 100 outlets across Karnataka and Kerala. CPCL’s expansion plans are still in early stages, with operational timelines and investment details yet to be announced.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Prerana.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Introducing “What the hell is happening?”

In an era where everything seems to be breaking simultaneously—geopolitics, economics, climate systems, social norms—this new tried to make sense of the present.

"What the hell is happening?" is deliberately messy, more permanent draft than polished product. Each edition examines the collision of mega-trends shaping our world: from the stupidity of trade wars and the weaponization of interdependence, to great power competition and planetary-scale challenges we're barely equipped to comprehend.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Can someone explain evergreening of patent and compulsory licensing in simple language

Thank you