The detours and contours of India's credit story

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Follow the Loans: India’s Credit Story

Why India’s Borrowing Costs Are Climbing Despite Rate Cuts

Follow the Loans: India’s Credit Story

The RBI wears many hats for the economy. But one of the things we finance nerds love most is the treasure trove of data it puts out. Monthly bulletins, regular surveys, chunky reports—you name it. If you want to track how the economy is doing, this stuff is gold.

One dataset we’re diving into today is the RBI’s monthly bank credit numbers. Simply put, this tells us where banks are handing out loans. And once you track that over time, it paints a surprisingly clear picture of where the economy is headed. After all, credit flows reveal how consumers are spending, where industries are investing, and what businesses are betting on.

So, in this piece, we’ll unpack the story behind the numbers—where credit is booming, where it’s slowing, and what that says about the larger economy. Moreover, just last month, we also did a story on how Indian banks were faring — naturally, India’s credit growth mirrors the action in banks’ balance sheets in many ways. We recommend reading that before jumping into this one to get a full view of what’s really going on.

Let’s get into it.

The Big Picture

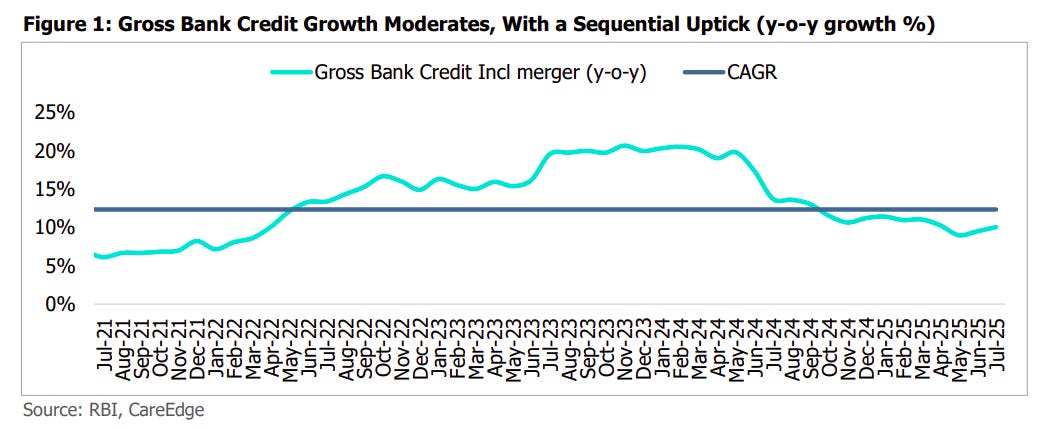

Let’s start at the top: overall banking credit growth. As we’ve been pointing out for a while, it’s been running below average. That’s just how credit cycles work. Sometimes banks are flush with lending, demand is hot, and the RBI steps in to cool things down—usually by hiking rates. Then the pendulum swings the other way: growth slows, borrowing dries up, and the RBI cuts rates to try and spark things again.

That’s exactly what we saw through 2025—RBI kept cutting rates to nudge people and businesses to borrow more.

But that easing cycle now looks done. The RBI’s latest MPC commentary suggests no more rate cuts, and bond yields are climbing too. Together, these hint that the worst of the slowdown may already be behind us.

For now, yearly bank credit growth seems to have steadied around 10%. Not great, but at least no longer sliding. And while we leave predicting the future to the experts, what we can do is dig into the segments driving (or dragging) this number.

Credit growth is split into four big buckets:

Agriculture – loans to farmers and allied activities

Industry – funding for factories, infrastructure, capex

Services – everything from trade and transport to IT and finance

Personal loans – housing, vehicles, credit cards, consumer loans

Here’s the picture: growth in agriculture and industry has been very weak. Together, they make up about 35% of total credit, and their slowdown is a big reason the overall number looks dull. On the other hand, services and personal loans—roughly 65% of the mix—have been a silver lining, growing at double digits.

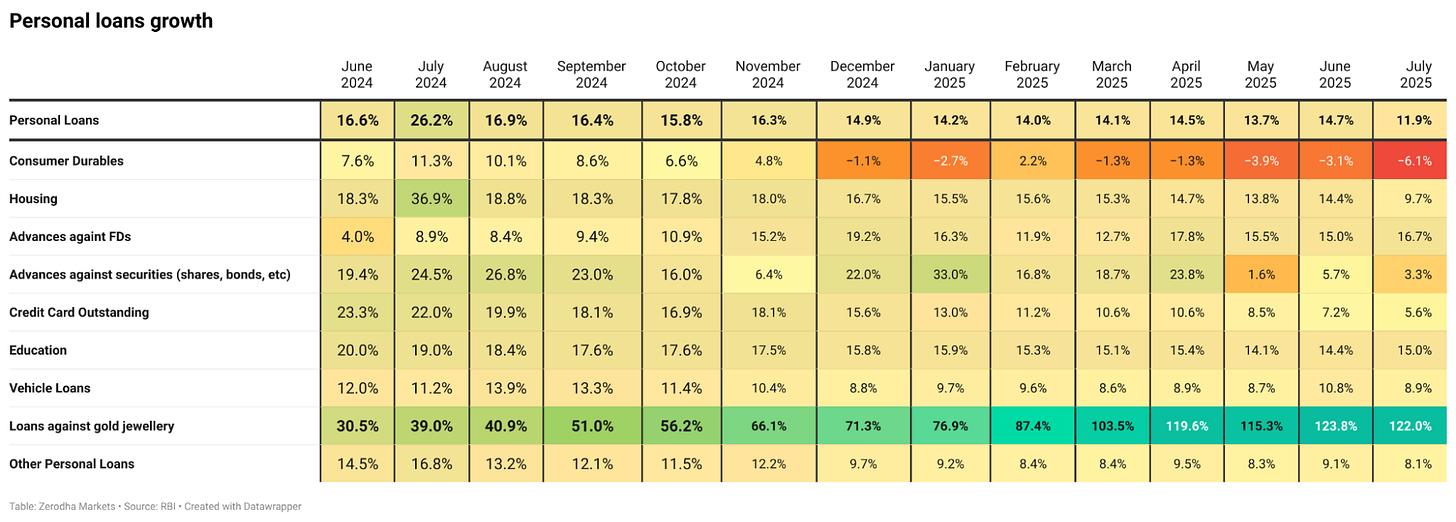

Personal loan growth, the biggest chunk of bank credit, is cooling. It slowed to 11.9% in July, the weakest since COVID. Given its size, any further deceleration here will make it harder for overall credit growth to pick up meaningfully.

On that note, we’ll be digging deeper into the biggest puzzle of India’s credit story — personal loans.

Personal Loans

This category covers all the loans banks extend to people like us, mostly for consumption. Within personal loans, housing loans dominate, accounting for nearly half the mix. Which means, if housing slows, then the entire pie shrinks significantly. And while growth hasn’t fallen off a cliff yet, it has clearly lost steam, growing just 9.7% in July 2025.

There are a few possible reasons. For one, NBFCs are outpacing banks in the housing space, especially in affordable housing where they’ve carved out a niche. Banks have largely let them run with it. Another reason is that banks may not even want to push too hard. Home loans are cheap, low-margin products, and with spreads already under pressure, stepping off the gas here makes perfect sense from their perspective.

The most worrying bit sits in credit cards. They make up 5% of personal loans, but their growth has slumped to the weakest since January 2015 — a full decade. Just a year ago, credit cards were among the fastest-growing categories, but now they’ve fallen to the bottom of the pile.

The likely explanation is that banks themselves have turned cautious. With delinquencies ticking up, they’re holding back on issuing new cards or raising limits. Sure, credit cards are high-margin products, as the people who own them are often among the richest in India, so the interest rates on them are also high. But that runs the risk of non-payments or even defaults, so restraint may benefit the system in the long-term.

Gold loans, though, tell a different story. They account for around 5% of the personal loan book and have been booming—averaging over 100% growth since March 2025. But here too, the headline number flatters a bit: part of the jump really came from reclassifying agri-gold loans into retail, and part came from a massive 47% surge in gold prices, which automatically lifted loan values.

But banks don’t just lend to people like us. Companies borrow too, and those loans fuel everything from factories to offices to expansion plans. The real question is: how’s loan growth looking on that side of the fence?

Services & Industries

Credit growth in the services sector is showing faint but steady signs of life. A big chunk of this lending goes to NBFCs, which take up about 30% of services credit, while trade—think distributors and kirana stores—accounts for another 11%.

For over a year now, credit flows to NBFCs have lagged behind overall bank credit growth. Part of that story goes back to 2023, when the RBI slapped higher risk weights on loans to NBFCs, making it more expensive for banks to extend loans to them. That rule was lifted earlier this year, but banks still aren’t rushing in.

Why? Because lending to NBFCs is a low-margin, high-volume business, and hence has little upside. On top of that, banks are wary of smaller NBFCs with heavy exposure to microfinance or unsecured personal loans. So, despite some de-regulation, caution remains. In response, though, NBFCs aren’t sitting idle. They’re increasingly tapping into bond markets and deposits for funding in order to reduce their dependence on banks.

Beyond NBFCs, other patterns stand out. Credit to commercial real estate—money for building offices and projects—has been slowing consistently. On the brighter side, tourism, hospitality, shipping, and computer services have all been attracting fresh lending. Aviation, though, remains stuck in a lull.

When it comes to industry, like manufacturing and big industrial units, credit growth looks like it may finally be bottoming out. Within the industry, the pain has been sharpest among large corporate firms, which still soak up nearly 70% of all industry loans.

Why the slowdown? Large companies have easier access to capital markets, and that’s where they’ve been going instead of banks, so the demand for bank loans has stayed muted. Add to that the fact that many are delaying major capex and investments.

The real action has been in MSMEs — something we’ve mentioned before on The Daily Brief. Their credit growth has consistently outpaced that of large industry, and as a result, their share of industrial credit has climbed—from 71.9% large corporates in July 2024 to 68.4% a year later. That may sound small, but it reflects a genuine shift. Policy support measures like ECLGS and CGTMSE, plus the broader formalisation of small businesses, have helped.

But let’s not forget — MSMEs are still too small in absolute terms to move the overall industry numbers. Moreover, it’s likely that even within MSMEs, it’s the largest firms getting better credit terms than everyone else. Unless large corporates return to the table and start borrowing again, industrial credit will likely stay stuck in low gear.

To sum up

Credit in India right now is a mixed bag. Personal loans are cooling, services are inching up, and MSMEs are quietly gaining ground while big corporates sit out. Overall growth seems to be bottoming out around 10%, but it’s too early to call a full rebound.

The cycle may be turning, yet the cracks in housing, credit cards, and large industry mean that we will need to pay close attention to how India’s credit story unfolds.

Why India’s Borrowing Costs Are Climbing Despite Rate Cuts

Our second story today is somewhat related to the first.

Most people obsess over the stock market — which makes sense, since it directly affects their portfolios. But the bond market often tells us just as much, if not more, about the economy. The problem is that not a lot of people pay attention to it.

So, we decided to take a closer look. And honestly, it looked strange at first glance.

Since the start of the year, the RBI has been slashing repo rates aggressively, front-loading cuts to jumpstart growth. In theory, this makes borrowing cheaper across the economy. On top of that, in August, S&P Global upgraded India’s long-term sovereign credit rating for the first time in 18 years, which is a big vote of confidence. You’d think investors would be very comfortable to buy Indian bonds, making them cheaper for the government to issue.

But — surprise — the opposite has happened. After the RBI’s huge 50-basis-point cut on June 6, bond yields spiked instead of falling. From a low of ~6.16%, they climbed to ~6.53% at the time of writing.

Usually, we don’t focus on giving quick-fix explanations for every market twitch, but this contradiction is too loud to ignore. The question is simple: if the RBI is cutting rates to boost growth, and India just got a credit upgrade, why is it suddenly costlier for the government to borrow?

Let’s dig in.

The demand-supply dynamic

At its core, finance is just demand and supply. Prices go up when demand is higher than supply, and fall when it’s the other way around. There’s even a running joke: whenever someone asks why the market fell today, the answer almost always boils down to “More sellers than buyers” — despite there being far more complex market dynamics behind this result.

Bonds aren’t all that different — except there’s a twist. The prices and yields of bonds move in opposite directions. So if yields are rising, it means bond prices are falling. And falling prices are usually a signal of weak demand, or an over-flood of supply, or both. That’s our starting point.

Weak Demand

On the demand side, buyers just aren’t keeping pace. The government and states are issuing mountains of long-term bonds, but the natural buyers — banks, insurers, pension funds, and FPIs — aren’t stepping up. The shortfall is pegged at around ₹1 lakh crore. That alone is enough to push yields higher.

Why aren’t these institutions buying? Well, each of them seems to have their own reasons:

Banks: The RBI is cutting back the Held-to-Maturity (HTM) cap from 23% to 19.5% of deposits. That means that banks are simply unwilling to hold more bonds till they mature — especially if their maturity period is long. With less HTM flexibility and rising losses on the accounts of banks, they’re cautious.

Insurers and pensions: Life insurers’ inflows are slowing, and the National Pension Scheme (NPS) has lifted its equity allocation cap from 15% to 25%. That means more fresh money is going into equity, actively taking away the allocation meant for long-term bonds.

FPIs: Foreign investors are small players here, but even they’ve been net sellers. Debt outflows hit ~$2.3 billion in April 2025 — the worst since COVID. A big factor is the India–US 10-year spread, which reflects the premium investors demand to hold Indian bonds which are riskier than US treasuries. The spread collapsed to ~200 bps, its lowest since 2004, making American treasuries relatively more attractive.

The confusion on what the RBI’s rate policy should be has amplified this problem. The RBI started the year by front-loading rate cuts, making traders expect an easy, dovish cycle. But in the latest meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee, it suddenly turned cautious, hinting at fewer cuts ahead. This caused worry among bond buyers. When there is a possible rate cut on the cards in the future, you’d continue buying bonds and enjoy the yields. But that wasn’t the case anymore.

If inflation risks return, then the RBI might hike the rates in the future. So investors right now will likely demand higher yields as compensation for taking on that risk.

Heavy Supply

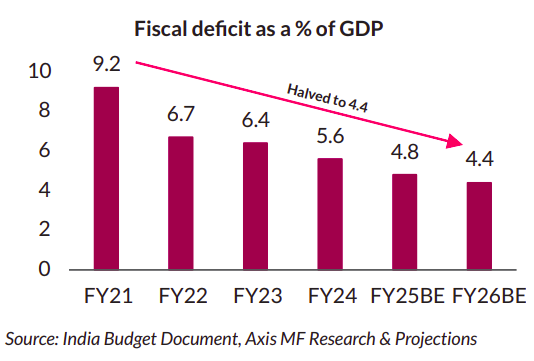

On the supply side, things aren’t looking any better. The government’s fiscal math is under strain.

GST 2.0 rate cuts may be politically popular, but they may also eat into fiscal revenues. The 8th Pay Commission, which will increase salaries for government employees, adds another layer of spending pressure, and income tax collections have actually declined between April and August of this year. All of this potentially points to higher borrowing needs, for which the government will raise bonds.

India had managed to steadily cut its fiscal deficit from the CoVID peak of 9.2% in FY21 to about 4.4% recently — a trend that looked encouraging. But that improvement is unlikely to last with the new GST reforms.

Both the Centre and the states are gearing up to borrow more. States alone are taking on 50% more debt than they did just two years ago, and what’s worse, they’re issuing longer-dated bonds. Long-term bonds are exactly what the market doesn’t need more of right now.

Meanwhile, the supply story has one more headwind that it could face soon — US tariffs.

The return of Trump-era tariffs directly targets India’s Russian oil purchases and broader trade practices. If those measures stick, India’s exports to the U.S. could shrink dramatically by any estimate you take.

Let’s visualize what the possible ripple effects of a trade shock might be. Lower export revenues weaken the current account, and it may force struggling industries to ask for state support. A current account deficit would put pressure on the rupee, which may call for interventions by the RBI to stabilize it. As a result, growth will slow, and the fiscal cost of cushioning the economy rises. To make up for this cost, the government may issue new bonds.

The bond market sees all of this coming. More borrowing, weaker revenues, global trade shocks — it all adds up to heavier supply and higher risk. And quite naturally, investors are demanding higher yields to absorb it.

What it means for the economy

Right now, the RBI’s cuts aren’t flowing through the system the way they should. Higher market yields are undoing the central bank’s easing, and you can already see the impact with fundraising deals getting delayed or pulled, like it did for HUDCO and Bajaj Finance. The bond market is basically saying: borrowing isn’t going to be cheap, no matter what policy rates do.

Part of this is about government finances. Revenues are being squeezed just as expenses are set to rise, which means more borrowing is on the way. And the way that borrowing is structured — with a heavy tilt toward long-term bonds — is clashing with a market where the usual big buyers have stepped aside. That’s why the yield curve is staying steep and borrowing costs aren’t easing.

Global pressures add another layer. The India–US yield spread has narrowed sharply, making foreign investors less enthusiastic, while trade tensions and tariffs could further strain India’s external position.

Unless borrowing plans are adjusted and the RBI steps in with clearer signals, yields are unlikely to soften meaningfully. That leaves the economy facing a higher cost of money at precisely the time it’s trying to accelerate growth.

The coming months will hinge on three things. First, whether the RBI is willing to get more active in the bond market, even in small ways, to break the buyers’ strike. Second, how the government structures its borrowing calendar, especially whether it cuts back on long-dated issuance. And third, the flow of money from big institutional players like insurers, pensions, and foreign investors. Any shift on those fronts could ease pressure quickly.

This story isn’t just about interest rates. It’s about the trust and credibility of institutions, and who’s willing to buy long bonds. Until those pieces line up, yields will stay elevated, and the economy will have to run harder — just to stand still.

Tidbits

India ups diesel shipments to Europe by 137% in August (Source)

India's diesel exports to Europe surged 137% year-on-year to 242,000 barrels per day (bpd) in August. This was partly in anticipation of the EU’s ban on fuels refined using Russian crude oil — a story we’ve covered. But analysts also attributed the surge to other factors: expected winter demand, and Shell’s decision to advance the maintenance of one of their European refineries.Apple continues to swing — and hit — big in India (Source)

Apple’s annual sales in India officially crossed $9 billion in the previous fiscal year. Since FY23, Apple’s India business has grown 1.5x. As part of a huge retail push, the phone maker also added two new stores in Bangalore and Pune this week.Amazon gets an NBFC licence in India via an acquisition (Source)

Amazon buys Indian NBFC Axio (earlier called Capital Float) in a $200 million deal. This is a step in Amazon’s direction to build a full-stack financial services business in India. They already have a mobile wallet licence, an online payment aggregator licence, and an insurance broking licence. This deal might finally allow it to also get into lending to consumers as well as small merchants / SMEs. Rival Flipkart already received an NBFC licence in June this year.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

We just started a new experiment - Plotlines?

Plotlines is an extension of our Chatter newsletter. While most financial analysis focuses on quarterly results and near-term changes, Plotlines takes a different approach. We analyze executive commentary from earnings calls and investor presentations to identify long-term, structural shifts that will shape industries for years to come.

Instead of chasing headlines, we look for strategic pivots, evolving competitive dynamics, and fundamental changes in how companies allocate capital. Each week, we'll highlight the most significant "plotlines" from recent corporate communications, focusing on comments that signal permanent changes in market structure, technology adoption, or business models.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Hi - There is one important point missing from the second story > that it is the short-term rates that usually move with the RBI policy rates - which have come down since the start of the RBI easing cycle (though I am not sure of the exact % decrease). 10-year yields usually move with growth expectations and fiscal considerations > which are facing pressure due to trade tensions and GST 2.0, as it is pointed out in the article. Please let me know if I am wrong.

Hi - I have one question. I don't understand how increasing loan prices would automatically lift loan values? Gold is only being used as a collateral here so unless borrowers are topping up their loans - which grows the loan amount - just an increase in gold price shouldn't increase gold credit?