The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics: a breakdown

Hi folks, and welcome to the Daily Brief!

Before we start, we at Markets by Zerodha would like to wish you a very happy Diwali! We hope you have an incredible time with your loved ones. You’ve certainly kept our year bright with all the love you’ve given us so far.

And like every year on Diwali, the Muhurat Trading session will take place this time too: on Tuesday (21st Oct) from 1:45 pm-2:45 pm. Muhurat trading has immense cultural significance for India, as every Diwali, brokers and merchants conduct a puja to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity. We hope that the goddess rains down riches on your investments as well 🙂

With that, let’s kickstart today’s episode of The Daily Brief!

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics: a breakdown

Inside the chaos of the global aircraft leasing market

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics: a breakdown

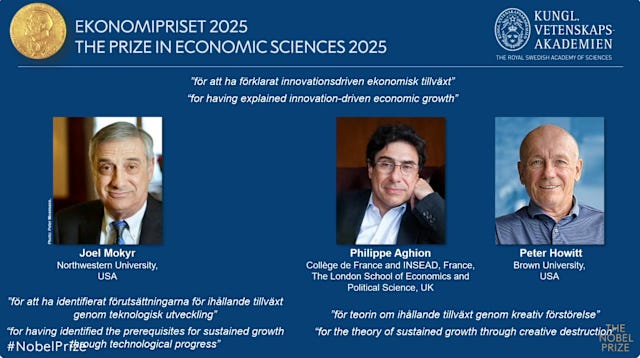

This year, the Nobel Prize in economics was awarded jointly to three people. One of the winners was economic historian Joel Mokyr, who shared the prize with economists (and team-mates) Phillippe Aghion and Peter Howitt.

However, the Nobel committee chose these two sets of people for a reason. Because, in a sense, both sets of people have all wrestled with a single question: how does economic growth work? Mokyr deals with how it began, while Aghion and Howitt deal with how it’s sustained.

So, we decided to summarize their life’s work, while also tying together the themes common to both of them, and how they apply to the real world. But, we also highly recommend diving into their original books and papers.

Let’s dig in!

How did economic growth even begin?

Let’s start with Joel Mokyr’s work.

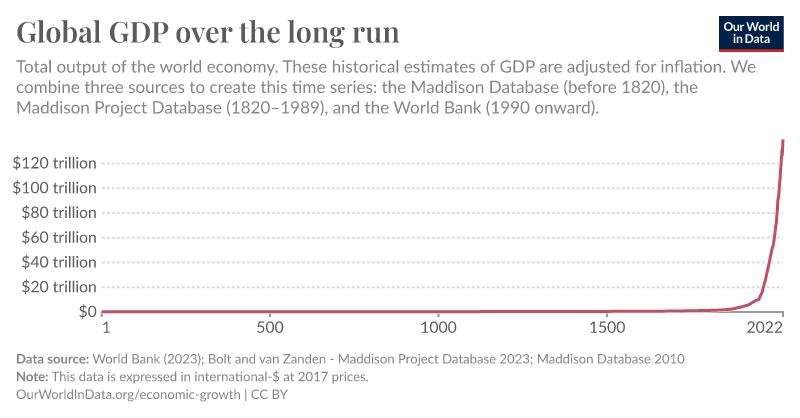

You don’t need to be a scholar to know how important the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th century is to humanity. It’s often considered the starting point of economic growth.

But, have you wondered why it took so long for the Industrial Revolution to even happen? Until then, economic growth basically seemed like a flat curve. Why did economic growth stall until this point? And why did the Industrial Revolution take place in the UK first?

These are, by no means, questions with easy answers. But Joel Mokyr has an interesting take on this. His answer is not the only one, or even the most definitive one. But Mokyr’s thesis has lots of power, and tells us a lot about our world today.

The power of knowledge

Mokyr’s answer centers on the role of knowledge in society.

He describes two types of knowledge. On one side is propositional knowledge, which requires understanding why things work—physics, chemistry, mathematics, and other aspects of science. On the other side lies prescriptive knowledge. That’s knowing how to actually do things—recipes, techniques, practical instructions.

Mokyr says that economic growth, as we know it, began when these two types of knowledge started interacting with — and feeding — each other. And that didn’t happen until the Industrial Revolution.

Here’s the thing: before the 1800s, there were plenty of inventions. For instance, Chinese engineers built blast furnaces centuries before Europe. Romans constructed aqueducts that still stand today. Medieval Europeans developed windmills. But these innovations were isolated. Without institutions to facilitate the diffusion of knowledge, breakthroughs didn’t compound systematically. They appeared, produced some benefit, then the process stalled out.

So, what changed? Well, Mokyr credits Francis Bacon, the famous 17th-century philosopher, who argued that the purpose of knowledge shouldn’t merely be to satisfy curiosity, but to improve the human condition. He believed strongly that natural philosophy and useful knowledge can be combined to solve technological problems. And that idea spread like wildfire among like-minded people over time.

So, why Europe? Why did the Industrial Revolution take place in Britain first?

Mokyr credits the political structure of Europe with why the Industrial Revolution took place there first.

Back then, Europe was not politically unified. Different regions were ruled by different entities and had different sets of laws. If you, as a scientist or philosopher, found one region to be too stifling, you could just move to another. No single authority could suppress you. This also incentivized states to compete with each other to relax their laws and procure talent.

But without a culture that promotes knowledge, Mokyr says, political structure is not enough. Europe’s scientists and scholars formed a loose, cross-border group called the “Republic of Letters”. They were committed to the free flow of ideas and the pursuit of scientific truths. This culture was sustained by institutions in various regions, like London’s Royal Society, or the Académie des Sciences in Paris.

It was this institutional support for openness to ideas, Mokyr says, that allowed the start of what’s called the Enlightenment era. Enlightenment was a belief in reason, that the world could be observed not by faith or tradition, but by science and cold, hard logic. Successes in practice validated scientific theories made in the lab — and science, in turn, improved practical techniques in the factory. Finally, theory and practice fed strongly into each other.

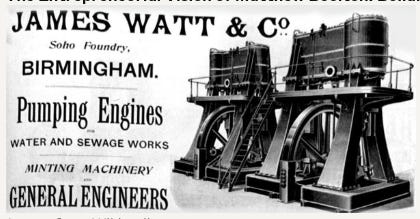

A great example of this is James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine. He understood the scientific theories around heat and pressure, and he applied those principles to improve the steam engine dramatically. Those improvements raised new questions about thermodynamics and energy conversion, which pushed scientific research forward.

At the time, Mokyr says, Europe was the only region in the world that had a combination of all these factors. And within Europe, the UK in particular had an abundant supply of such people, like Francis Bacon, the economist Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, James Watt, and so on. That’s why, as Mokyr says, the Industrial Revolution started there rather than, say, France or the German states.

A culture of innovation

So that’s what Mokyr emphasizes on. For economic growth to work, openness to ideas, scientific inquiry, and institutions that support these ideas are necessary. Without these, economic growth will cease to work. In fact, Mokyr strongly believes that knowledge matters just as much as capital or technology.

But Mokyr identifies another critical factor: societies had to be open to change.

New technology always threatens someone else’s existing interests. It makes established skills worthless and obsoletes expensive equipment. It undermines local monopolies and disrupts social hierarchies. Throughout history, powerful groups blocked technologies that threatened them. Mokyr has also documented such resistance to technological change across history.

And this is where the work of Aghion and Howitt comes in.

The power of creative destruction

At Markets by Zerodha, we’re in the business of tracking how companies live, and also how they die. Both these things are tied to each other like yin and yang. As a whole, this describes one of our favorite concepts in all of economics and finance: creative destruction.

Creative destruction is a concept originated by an Austrian-born economist named Joseph Schumpeter. Inspired by the work of Karl Marx, Schumpeter came to a crucial conclusion about the economy we live in. He said that capitalism is a constantly-moving process where new technologies keep replacing old ones.

But such a technological shift comes with a lot of turbulence in the market. While new companies get created to implement new technologies, older firms go bankrupt as their stocks fall to zero. This also causes a rise in unemployment as older jobs go obsolete. However, this turbulence is central to innovation — and hence economic growth. They go hand-in-hand.

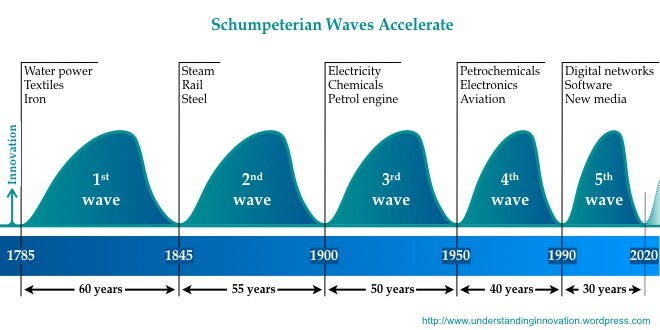

This process causes industrial revolutions every few decades, where new waves of technologies keep appearing. The Industrial Revolution of the 1800s, Schumpeter says, was merely the beginning.

In fact, there are so many episodes of The Daily Brief that make for great examples of creative destruction. Be it lab-grown diamonds replacing natural ones, or how Intel lost out on the chip race, or the rise of solar in the world’s energy mix, or EVs slowly replacing gasoline vehicles, or, of course, the rise of AI. It’s everywhere for you to see.

India is no exception to cycles of creative destruction, either. Fund manager Maneesh Dangi highlights an incredible statistic on this in a piece with IIM Udaipur:

“If you had invested in the top 20 Indian business groups of the 1960s, more than half would have disappeared by now. Names that once dominated—Thapars, Scindias, Mafatlals—have faded into history. Corporate mortality is real, yet most investors obsess over how firms succeed rather than why they fail.”

Putting numbers to theory

For a long time, creative destruction was just a theory. However, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt made a rigorous, mathematical model out of it. And this model was a vast departure from the other economic models that existed.

In the 1990s, Aghion and Howitt wrote a paper on modeling creative destruction. In this model, firms invested in R&D actively to jump ahead of the race. However, investing in R&D is a highly risky process. So, to incentivize such a process, a successful innovation is made to win a temporary advantage through extra profits. This advantage could take the form of patents, first-mover advantages, and so on.

But that very success invites the next leap by a rival, who might even replace you. As this keeps happening, economic growth increases.

Now, why was this model so revolutionary? Here’s the thing: until then, in economics, innovation was treated as this thing that just happened on the side. It was considered important, but never part of the model itself. Most existing models at the time instead focused on the idea that the source of economic growth was how much people saved and invested in factories, machinery, and so on. Everything was analyzed from the point of view of investment.

The model by Aghion and Howitt changed everything. It showed how actual business life flowed into macroeconomic growth theory. Entry, exit, bankruptcy, workers losing jobs, entire industries disappearing, new ones arising. It reflected the real world far more than past models.

The relation between innovation and competition

Through this model, Aghion and Howitt also explored an interesting relationship between innovation and competition. Innovation creates two contradictory, push-and-pull forces that influence the competitive structures of various industries.

On one hand, when you make an innovative breakthrough, future innovators can piggyback on your work for far cheaper and build new innovations, even though you bear the initial risk. So you don’t fully capture that future social benefit—the next company does.

On the other hand, though, when your innovation succeeds, it takes away your competitors’ profits and even market share, putting them on the backfoot. This increases inequality between firms.

Now, neither force is good or bad in and of itself, except in extremes. With too much competition, though, nobody can earn enough incentive to justify the massive risks of innovation. With too little competition, incumbent firms face no serious threats, so why invest in expensive and risky R&D? They can just monopolize the market and protect their profits by blocking innovations by others.

But, Aghion and Howitt discovered that these dynamics created an inverted U-shaped relationship between innovation and competition.

Here, Aghion and Howitt find that innovation (measured by R&D spend) thrives not in the extremes, but in the middle range. The competitive pressure is strong enough to motivate them, but the potential rewards are large enough to justify the investment. Firms try to escape neck-and-neck competition by spending more on R&D, continuing the push-and-pull. The trick, however, is to manage this push-and-pull sustainably using policy.

Some policy implications

When you think about it, Aghion and Howitt’s work has huge policy implications.

For one, how should competition be regulated by the government? Should regulators break up big tech companies like Google, NVIDIA and Microsoft?

Well, it depends. If those companies are innovating rapidly and the competition for “the next big thing“ is intense, breaking them up might actually reduce innovation. But if dominant firms are using their market power to block new entrants and innovations, then intervention could restore the healthy competition that drives innovation.

Secondly, how can the government manage the destructive parts of creative destruction? After all, it involves people being let go from their jobs. However, Aghion and Howitt’s work has shown that it’s indeed possible to manage it, if not fully remove it. The policy principle that emerges is: “protect workers, not jobs”. That means investing in retraining people and providing strong social safety nets in between such massive transitions.

These questions are similar to the ones Joel Mokyr asks: what kind of cultural or institutional structure works for innovation? How important is openness to change — and how do we manage the pros and side-effects of such openness? And that’s what ties the 2025 Nobel Prize together.

Conclusion

The Nobel Prize has been awarded to three people who have dedicated their lives to finding out what makes economic growth tick. Their answers find common ground in understanding the role of the openness of ideas, culture and competition.

Their answer is not the final word on the question of economic growth, and there are plenty of debates around their ideas. But they’ve certainly opened new frontiers when it comes to this question.

We’ve barely touched on what these questions mean for future innovations, especially AI. There’s a worry that not only will AI will displace many jobs, but also, its benefits might just be concentrated in a few hands, rather than be widespread.

However, as Mokyr, Aghion and Howitt show, it is indeed possible to manage this whole process in a sustainable way. We’ve done it many times before.

Inside the chaos of the global aircraft leasing market

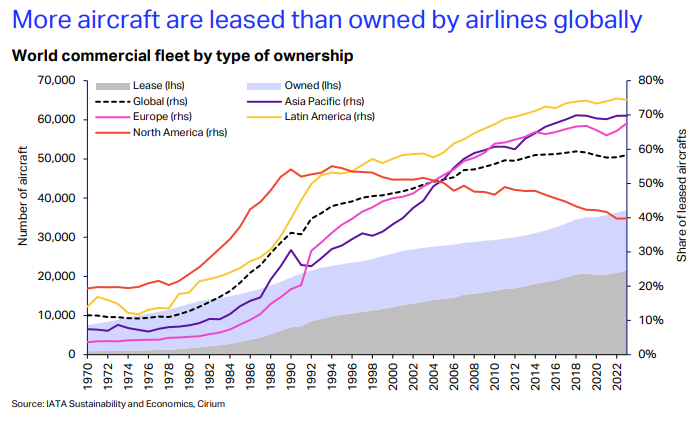

Last week, we examined why passenger aircraft manufacturing is a duopoly between Boeing and Airbus. We mentioned that over 58% of the world’s commercial fleet is not purchased outright, but leased. But we didn’t dive deeper into this.

So, we decided to write a separate piece on it. This market as it has its own unique quirks, market structure, and its own geopolitics.

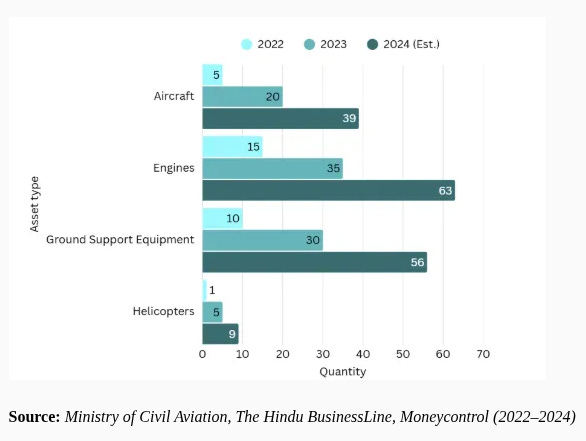

Moreover, India is making serious moves in this business now. Last week, Air India’s aircraft leasing arm got a loan of $215 million from Standard Chartered and Bank of India. This is also the first commercial aircraft transaction to be structured with a borrower located in GIFT City.

That’s no coincidence — GIFT City (that we also covered recently) is trying to be a global aircraft leasing hub. But that’s not going to be easy.

To know why, let’s dive into the chaos of aircraft leasing.

Why lease and not buy?

In our earlier piece on the aircraft duopoly, we had mentioned why airlines like Indigo, Emirates, and so on prefer to lease their planes rather than buy them outright. But we’ll summarize it again.

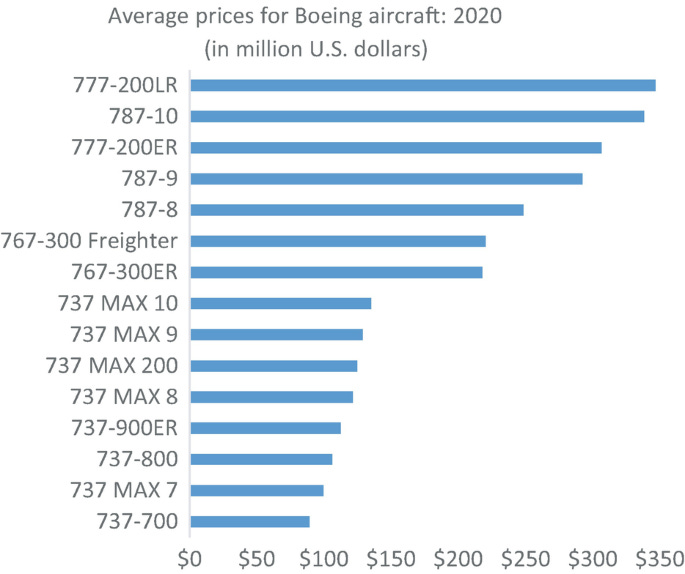

Firstly, aircraft are extremely expensive, risky assets, costing hundreds of millions of dollars. However, they depreciate really quickly in value. Airlines also operate on razor-thin margins. Tying up so much money in depreciating metal could potentially be suicidal.

Secondly, planes can take a whole decade to make and deliver. Predicting what consumer demand for flights will be like in 10 years’ time is extremely difficult. Economic shocks, pandemics, and shifting consumer preferences make buying fleets a really expensive affair. It is an extremely cyclical industry.

So, to make these problems more manageable, airlines lease planes instead from specialized aircraft lessors, usually for 6-12 years. Instead of huge capital expenditure, airlines pay predictable monthly rent. This preserves precious capital that can be used elsewhere. Crucially, it also transfers the risk of what a plane will be worth 20 years later to the lessor.

Leasing originated in the 1970s — partly because airlines had excess plane capacity that remained idle. Lessors entered the game by buying those planes, and then renting them out to other airlines. The leasing market grew over time as it allowed airlines to scale without burdening their balance sheets.

But, the biggest inflection point for the market was the 2008 global financial crisis. As asset values fell like a bomb, airlines were even more disincentivized to own planes since their balance sheets had crashed. Banks were also unwilling to finance their purchases since anything airlines offered as collateral was useless at this point. So, lessors found a huge window to take over this game.

Anatomy of an aircraft lease

However, the flexibility offered by leasing doesn’t come cheap. Aircraft lease agreements have really strict conditions for the airlines that borrow planes. The conditions have one goal: ensure that the value of the plane remains as high as possible by keeping wear and tear minimal.

One major condition in the contract is a clause called “hell or high water“. What it says is that, no matter what — be it technical failure, regulatory pinch, rain or shine — the airline has to pay rent to the lessor. Operational risk is not the lessor’s problem at all. And this is upheld strongly by the courts.

But this is hardly the start of how strict the contract can get. Leases impose strict requirements on how an airline can operate, too. For instance, airlines face strict caps on flight hours and cycles. They cannot modify cabin interiors without consent from the lessor. Lessors may also prevent planes from flying into areas that are sensitive to geopolitical risks. The reason is simple: in such areas, the lessor can’t repossess the plane. And as we shall see, this risk is quite real.

Leases also put a mandate on how airlines can replace parts, requiring them to source only parts from the original manufacturers (OEMs). This is despite the fact that the cheaper Parts Manufacturer Approval (PMA) components – which are equivalents certified by aviation authorities — help them save costs. But lessors argue that PMA parts create negative market perception, and would hence decrease asset value.

But if you thought that the expiry of the lease might ease things, you may be wrong. In fact, delivering the plane back to the lessor is when the conflicts increase. Leases specify exhaustively detailed requirements for how aircraft must be returned—a process that can begin 24 months before lease-end. Failure to meet any condition triggers substantial penalties.

For instance, in 2011, US Airways returned planes to Wells Fargo with a ~10% lower maximum take-off weight (or MTOW) compared to when it was first lent. Wells Fargo claimed this as a breach of contract, with the penalty being twice the monthly rent. While the actual rent amount wasn’t disclosed, the court sided with Wells Fargo.

Such contracts provide immense leverage and power to lessors over airlines. Smaller airlines and those with weaker credit often face “take it or leave it” terms.

The global landscape

Now, let’s move on to the geographic spread of the market.

The leasing market concentrates in two nations: Ireland and Singapore. But this isn’t really by accident. These countries offer huge advantages to lessors.

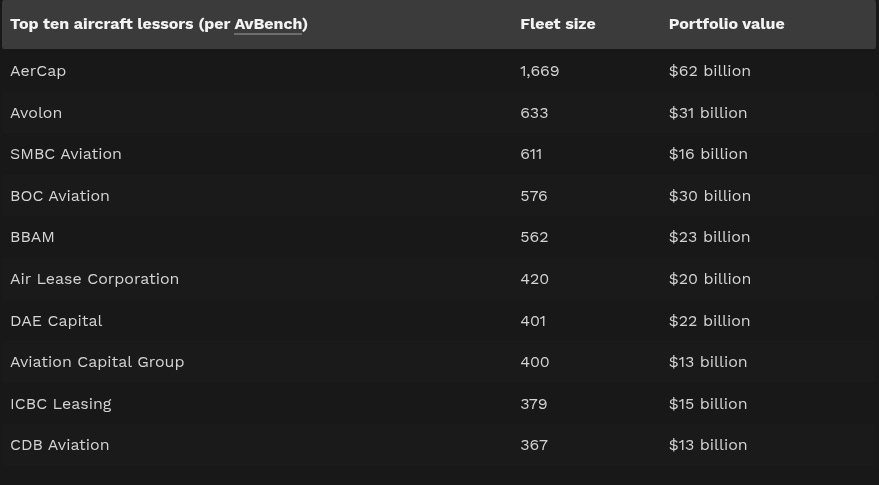

Ireland, for instance, manages over half of the world’s leased fleet. Its dominance traces to the 1970s, with one of the first lessors — Guinness Peat Aviation (GPA) — being founded in the country. Many ex-alumni of GPA went on to start or lead other major lessors, like AerCap (which is the world’s largest aircraft lessor), Avolon, and SMBC.

What helps Ireland is a very low 12.5% corporate tax rate on trading income. This is complemented by bilateral agreements with multiple countries that minimize taxes on lease payments. Ireland was also an early adopter of the 2001 Cape Town convention, which made it easier for creditors to repossess aircraft upon airline default.

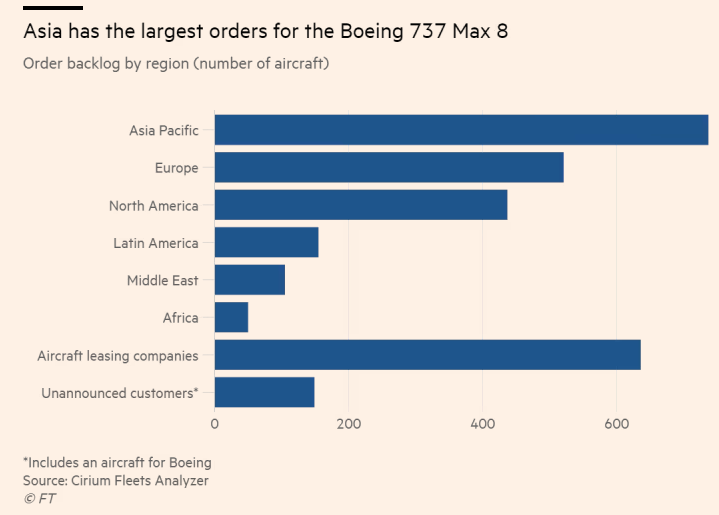

Singapore, too, has benefited from similar reasons: providing high ease of business, tax concessions, creditor-friendly rules, and some of the deepest capital markets in the world. But most importantly, Singapore has benefited from a major tailwind: recently, Asia has become one of the most important sources of aircraft demand. In fact, Airbus says that over the next 2 decades, Asia will make up 46% of the world’s demand. Singapore sits at the center of this wave that will only continue to rise.

Say hello to Chinese ownership

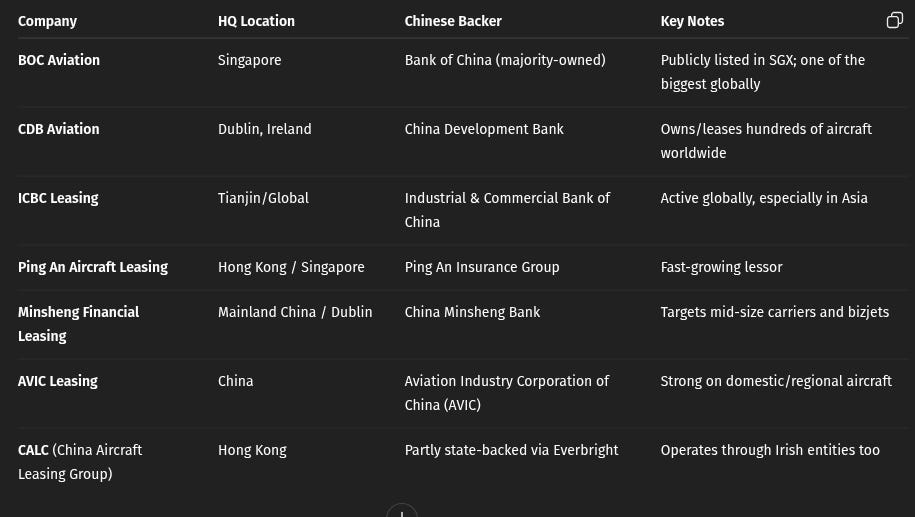

But analyzing the market by where the lessors are headquartered misses a critical dimension: ownership structure. And if you look at the table below, you might spot a common theme in the ownership of some of the biggest lessors.

Yep, that’s right. China has become a huge source of financing for global and domestic lessors. And China’s strategy was driven by 2 reasons: a) to reduce reliance on Western finance, and b) to create a funding ecosystem to support their own aircraft manufacturer, COMAC.

So, fueled by their system of cheap state-backed loans, Chinese lessors grew explosively. They even acquired established Western firms—Bohai Leasing, for instance, bought Dublin-based Avolon for $7.6 billion. Today, Chinese players like ICBC Aviation, BOC Aviation, and so on are among the biggest globally.

Geopolitical risk

China’s rise has created new kinds of geopolitical risks. Since the US-China trade war, global lessors are looking to hedge against the Chinese market. But it won’t be easy — China is officially the world’s largest market for airline lessors.

The Ukraine war, in particular, shattered any remaining illusions about aircraft being politically neutral assets. With flights being grounded in Russia, lessors were filing insurance claims worth billions of dollars. Western sanctions required lessors to terminate Russian airline leases and repossess aircraft. In response, Russia banned aircraft exports, effectively making repossession impossible.

In the matter of a short timespan, a war and the resulting sanctions changed the global market overnight.

India’s GIFT City Gambit

In all this chaos, India sees an opportunity.

Our airlines operate over 80% of aircraft on lease, with the vast majority structured through Irish and Singapore entities. This creates two vulnerabilities: billions in annual foreign exchange outflow through lease payments, and exposure to foreign legal and regulatory regimes.

Through GIFT City, India wants to build a big domestic lease market for itself to compete with Ireland, Singapore, and even China. To achieve that outcome, it is offering a variety of sweet incentives: like 10-year tax holidays on profits, zero withholding tax for non-residents, complete GST exemptions, and so on. The legal backstop is the 2025 Protection of Interest in Aircraft Objects (PIAO) Bill, aligning Indian law with Cape Town Convention principles.

Early results are promising. By early 2024, 33 leasing entities had registered in GIFT City, with over 200 aviation assets worth $1+ billion leased from the hub. Air India has also established a leasing unit there.

But significant challenges remain. International lessors remain cautious—the bankruptcy of the Indian airline Go First exposed difficulties lessors faced in repossessing aircraft. This has reinforced skepticism about the enforcement of creditor rights. Plus, it’s going to be hard to take away business from established, highly-trusted hubs like Ireland and Singapore.

Conclusion

Today, aircraft leasing has evolved from a niche financing tool into the indispensable financial engine of global aviation. It evolved quite naturally due to the needs of airlines and banks, and has massive complexities that aren’t found in other leasing markets.

But it’s no longer just about economics. The pushes by China and India show how control over aviation finance is viewed as an instrument of national power. The Ukraine war confirmed that sovereign actions can override commercial contracts.

The future of what was already a complex market has just turned far more uncertain.

Tidbits

Indian quick-commerce platform Zepto raised $450 million at a $7 billion valuation, up from $5 billion last year, bringing its cash reserves to $900 million as it prepares for an IPO.

Source: ReutersChinese automaker BYD is recalling over 115,000 Tang and Yuan Pro vehicles (2015-2022) due to design flaws and battery issues, marking its largest recall following previous safety-related recalls totaling approximately 104,000 vehicles.

Source: Economic TimesIndian Oil Corp and Hindustan Petroleum Corp purchased 4 million barrels of Guyanese crude from Exxon Mobil for late-2025 or early-2026 delivery, marking India’s first imports from the South American producer.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Manie

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Hi guys - love your work. In the second story, would have loved to read more on the economics of leasing vs. owning airplanes - like more numbers. Not sure if its something that is easily available, but could be interesting to look at how the decision affects an airline's P&L over the long-term.

The economics of CREATIVE DESTRUCTION aims to make way for current technology to boost economy and thereby the quality of life. Unfortunately CREATIVITY DESTRUCTION wil disrupt the way for current technology and will bring obstacles to boost economy and block the possible improvement in the quality of life.

Therefore CREATIVITY DESTRUCTION by talent suppression will not only cause damage of intellectual property but also cause damage of knowledge resources. In other words Talent suppression and grounding of creativity will disable economic development of a nation.

I am of the view that aforesaid creativity destruction or talent suppression is WORSE THAN CORRUPTION. In corruption some one is benefited, though illegally; Whereas in CREATIVITY DESTRUCTION nobody is benefited. When the cat steals the milk, its belly is filled ; when the snake bites its belly gets nothing.

The Government should enable creating an environment to transform creative ideas and techniques to realise Intellectual Property. Suppression of talent vis- a-vis CREATIVITY DESTRUCTION by any person holding authority in Government institution or corporate sector should be legally dealt with as a punishable offence by law. This suggestion is made in public interest.