The sky’s the limit — for only two aircraft makers

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Behind the duopoly of passenger aircraft

India’s Critical Minerals Moment: From Vulnerability to Value

Behind the duopoly of passenger aircraft

Recently, the board of Airbus held its first-ever meeting in Delhi with government officials and Indian airlines to discuss manufacturing planes domestically. This was a clear signal that India’s aviation market has arrived, with local airlines having over 1,000 aircraft on order. To meet this growing demand, the Indian government has been pushing aerospace giants to set up manufacturing under the “Make in India“ initiative.

This piece of news got us thinking about a different question, though: every passenger plane you’ve ever flown on — and we literally mean every single one — was made by either Airbus or Boeing. Think about it. In a world where we have dozens of brands for cars and phones, the passenger aircraft industry is just two companies eating up all the market share.

What is it about aviation that has such a weird and unique market structure? The answer reveals one of the most brutal industries, where even aerospace superpowers with unlimited government backing struggle to break in.

So, we decided to look into what makes commercial aviation so difficult.

(If you’re interested in diving deeper, we highly recommend this piece by Construction Physics.)

Double whammy

Every industry has its own cycles of how it produces things, and how it sells things. Understanding that in the context of commercial aviation is all you need.

A long product cycle is one that requires a lot of R&D and capital investment, and is therefore both time-taking and extremely costly. In a long sales cycle, the customers are other companies and institutions who buy low-volume high-value items. Such deals require long decision times, and therefore high amounts of trust. Naturally, product cycles also influence sales cycles, and vice versa.

And different industries have different cycles. Pharma, for instance, has a long product cycle, the medicine itself sells quickly in fairly large volumes. Clothes have fast product and sales cycles — making them and selling them are relatively easier than other industries. Defence, on the other hand, has few customers, doesn’t sell in high volumes like clothes, and is high-value. Here’s a very rough, illustrative diagram showing this spectrum.

Did you spot commercial aviation? Both its product and sales cycles are so long and tough, they can break the patience of even the calmest, most peaceful monks.

Let’s start first with how its product cycle works.

Cloudy with a chance of product failure

Today, developing a new commercial aircraft routinely costs $20-30 billion — by no means a small amount. Even back in 1965, when Boeing launched the iconic 747, they spent over $1 billion while being valued at just $375 million — betting more than the entire company on building a new commercial plane model. And building a plane, from initial design to final delivery, can take nearly a whole decade.

The struggles don’t end here, though. When starting to make planes, manufacturers typically lose money on every unit, making profits extremely elusive. Between 1970 and 2010, Boeing barely averaged a 5% net profit. In recent years, it’s consistently been recording losses.

You might ask — why is profit so hard to come by? Can’t you just add more seats in a plane to increase its capacity and squeeze more juice out of one jet? But that’s the thing: it’s not as simple as adding seats to make planes more efficient. Just one extra seat will change the weight distribution and fuel efficiency of the plane, requiring further testing and re-certification. There’s no quick iteration here.

This is what makes passenger aircraft a wholly different business from other kinds of aircraft. Fighter jets, for example, while advanced, are light in weight because they only need to house 1-2 seats, while not being used for commercial purposes. Passenger aircraft, though, are far bulkier, harder to make, and need to be commercially ready.

This brutal reality is also why you rarely see brand-new designs. The Airbus A320, which is the most widely used model among Indian passenger airlines, was launched in 1987. It was the first plane in Airbus’ A320 family, and all other models are just minor updates to the original. Each update costs only 10-20% of a clean-sheet design.

The regulatory gauntlet

Safety certification is a huge part of the product cycle. Testing alone takes about five years for a large airliner—five years of spending billions with zero revenue. And that makes sense — a safety issue is the difference between life and death. In fact, Boeing had to fully shut down production of the 737 MAX right after Alaska Airlines experienced a near-crash in 2024.

One might also say that the strategy of manufacturers to merely update extremely-old planes could lead to safety issues. For instance, the 737 MAX was a derivative of the 737 built in the 1960s. While Boeing made this decision to save time and costs, it led to major design compromises because the old system couldn’t be fully adapted to new technologies.

A supplier ecosystem you can’t replicate

Another feature of the product cycle of commercial aviation is its extremely sticky supplier ecosystem.

A modern airliner is a puzzle of a million parts flying in tight formation. Boeing and Airbus have spent decades building supplier networks—hundreds of major suppliers and thousands of smaller ones—all working in perfect sync. Engine makers like GE and Rolls-Royce invest billions in developing new engines, betting on specific aircraft programs.

For new entrants, this ecosystem is nearly impossible to replicate, especially when safety regulations are so tight. The best suppliers are already deeply committed to Airbus and Boeing, who’ve built decades of trust. As Airbus’s CEO Guillaume Faury noted, assembly is far easier, making up only 7% of an aircraft’s value. Building its supplier ecosystem, though, is far harder.

The sales cycle from hell

Now, how these aircraft are sold to airlines like IndiGo.

Planes are expensive — a single narrow-body aircraft like an Airbus A320neo lists around $110 million. The market for them is pretty small; in a good year, barely 1,000 units get delivered. Since the product cycle is so long, purchase decisions take years. And they are heavily relationship-driven, involving negotiations on price, customization, training, and so on.

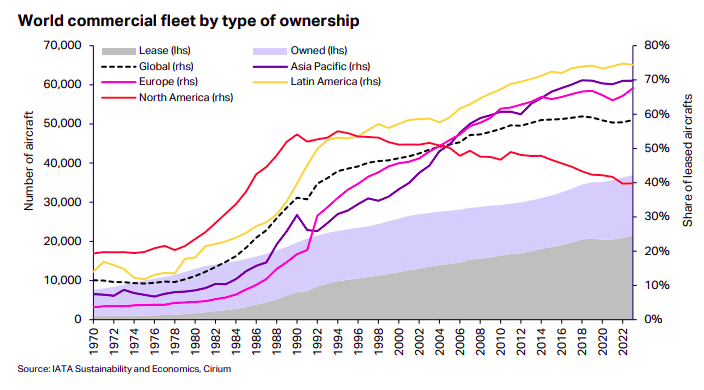

But airlines usually don’t buy planes outright. In fact, ~58% of commercial aircraft are actually leased, and there are strong reasons for it.

Here’s the thing: it’s very hard to forecast how many people will fly 10 years from now. Within a single product cycle, the entire market can change. Airbus, for instance, fell into huge losses with the A380 because of a misjudgment of how air travel will evolve. Additionally, planes depreciate really quickly in value, making them unprofitable to own in the short-term.

Since forecasting demand is hard, airlines often cancel their aircraft orders. In 2023 alone, there were 352 aircraft order cancellations globally. In fact, because of this, Airbus and Boeing deliberately overbook orders that they can’t meet in a realistic timespan — simply because they expect some orders to inevitably drop.

In such a situation, leasing makes more sense than owning a plane. If you don’t want a plane 5 years later, you don’t have to worry about its resale value if it’s leased. As an airline, you can quickly adjust capacity. However, aircraft leasing is its own hugely complex world that we can only cover in a separate piece.

Unbeatable network effects

What’s more, sales are extremely sticky. Airlines usually commit to a single fleet type. IndiGo built its fleet almost entirely with the Airbus A320 family of planes; in 2023, it placed a record order for 500 more A320s, the largest single purchase in aviation history. Southwest Airlines operates only Boeing 737s across its entire fleet.

The reason is simple — pilots need type-specific training, and spare parts are hard to interchange between types. Switching to a different plane model, therefore, requires incurring extra costs as their cockpits and systems can be vastly different. So, it comes cost-efficient to have fleet commonality that keeps getting updated over time.

This also implies that airlines value continuity—they know Airbus or Boeing will build as per their need. Buying from a less-established player feels far more risky. And a new jet must be significantly better to entice airlines to overcome switching costs — which, as the product cycle shows, is really tough.

A brief history of the duopoly

Now that we know how hard it is to build and sell aircraft work, let’s see how Boeing and Airbus have managed to capture virtually the entire market.

By the 1990s, virtually all Western jet manufacturers had consolidated into two giants. Boeing, founded in 1916, survived competition to become the last US maker of large passenger jets. Airbus formed in 1970 as a European consortium of French, German, British, and Spanish firms that joined hands to compete with Boeing’s monopoly.

Both have received — and continue to receive — massive government support. In fact, given that this industry is so hard, government support is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for success. After COVID-19, for instance, the US carved out a $17 billion loan fund specifically for Boeing. It’s a company that’s considered crucial to national security, and hence cannot be allowed to fail.

Intense Competition, Thin Margins

However, despite being a duopoly, Airbus and Boeing don’t really collude with each other. On the contrary, they compete fiercely.

Boeing was long dominant until Airbus’s aggressive push in the 1980s and 1990s. By 2019, though, Airbus had surpassed Boeing as the world’s largest aerospace company by revenue. And this was primarily because of innovation.

The Airbus A320 was a whole new paradigm compared to what Boeing had. It developed the first full set of digital controls on a cockpit. It was also more fuel-efficient than Boeing, This put Boeing on the backfoot, forcing them to rush production of the 737 MAX. That rushed decision led to their design and software issues, which have caused many tragic crashes.

This competition also drives deep discounts, eating further into margins. It’s a duopoly where much value goes to airlines through cheaper prices while manufacturers bear enormous risks.

The A320 and 737 families together account for nearly half of all passenger planes flying globally. No third player has been able to make a dent to this reality, and it’s not really for a lack of trying, either.

Jet lag

Many countries, both developed and developing ones, have tried — and failed — to create a rival to this duopoly.

Canada, for instance, had Bombardier, which developed the CSeries — a technically excellent jet. But development costs nearly bankrupted the company. Facing pricing wars and US tariffs, Bombardier sold the program to Airbus in 2018, exiting passenger aircraft entirely.

Brazil’s Embraer has succeeded in small, regional jets, but is struggling to make bigger ones with more seats. In 2018, Boeing agreed to buy 80% of Embraer’s commercial division, which would have helped them scale up. But, in 2020, amid the 737 MAX crisis and the pandemic, Boeing canceled the deal, leaving Embraer stranded without a clear path.

Then, there’s China with its heavily state-backed Comac. The biggest customer in its order book is currently the Chinese government. Its top passenger model, the C919 is technologically solid. But it lacks international certification, while relying too much on Western engines and avionics. So far, only a single non-Chinese airline — Indonesia’s TransNusa — uses the C919.

Even giants that made advanced fighter jets have failed here. Lockheed Martin, a powerhouse in military aircraft, exited commercial aviation in 1981 after the L-1011 TriStar lost $2.5 billion.

The failures can easily fill up a book — be it Japan’s Mitsubishi, Russia’s UAC, advanced fighter jet makers like Lockheed and Fokker, and so on.

500 (air)miles away from home

The commercial aviation duopoly isn’t the result of anti-competitive behavior. It’s the natural outcome of an industry with perhaps the most brutal economics in all of manufacturing.

One has to be too ambitious — or insane — to want to start a passenger aircraft company. Even the most well-capitalized, well-supported, technologically-advanced companies can’t survive. While things might change eventually, for the foreseeable future, if you’re boarding a standard passenger jet anywhere in the world, it was certainly made by Airbus or Boeing.

The duopoly isn’t unbreakable because they’re unbeatable. It’s unbreakable because the economics of breaking in are impossible to justify.

India’s Critical Minerals Moment: From Vulnerability to Value

No matter where you look, critical minerals are everywhere.

Lithium, cobalt, and nickel, for example, form the backbone of high-density batteries. Rare earth elements enable powerful magnets in cars. Silicon is a necessity in solar panels and semiconductors. And this is hardly scratching the surface of where all critical minerals are used, making them just as indispensable to the world today as oil.

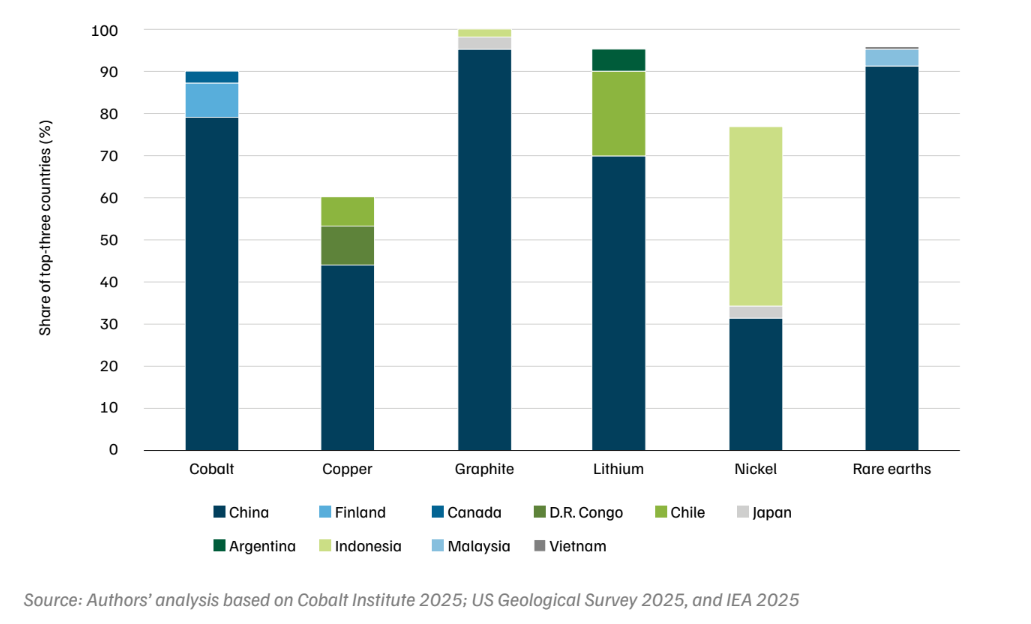

And, as we’ve covered before, the critical minerals race is geopolitical. Supply chains today are highly concentrated in just a few countries. A single dominant player, China, refines an outsized share of the world’s battery and magnet ingredients, leaving others vulnerable to export restrictions or supply shocks.

For India, this moment presents both a warning and an opportunity. The warning: relying on imports for critical minerals could undermine India’s energy transition and strategic industries. The opportunity: by acting now, India can turn its resource vulnerability into a strategic advantage.

A new, in-depth report by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), “Making India a Hub for Critical Minerals Processing”, shines a light on how India might seize this moment. Let’s dive into what the report says.

Global Trends

The story inevitably begins with China’s dominance — not just in mining, but also refining.

In 2024, for instance, China alone processed over 90% of global rare earth elements and natural graphite, nearly 80% of the world’s cobalt, and about 70% of lithium chemicals. Other countries lead in mining — Indonesia digs up the most nickel, Australia supplies over a third of lithium ore. But much of their output — which isn’t very useful in its raw form — still ends up shipped to China for refining.

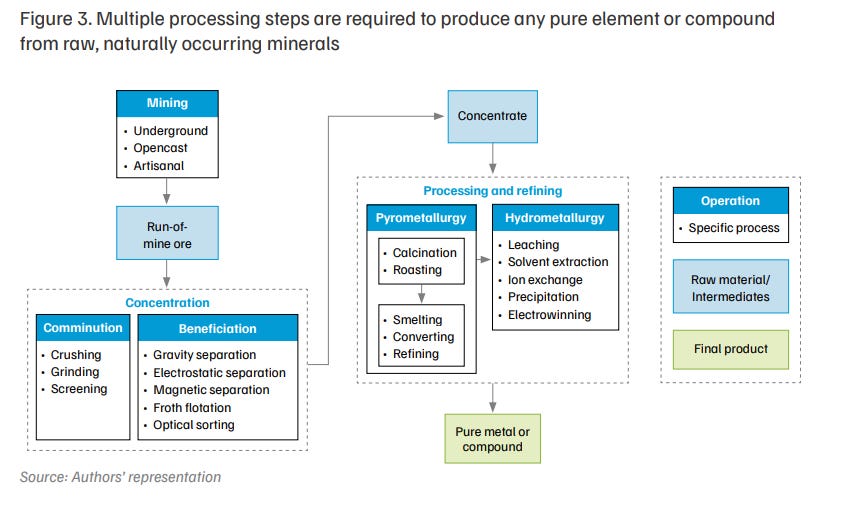

The thing is, mining tends to hog the headlines — the excitement of a new deposit discovery or a mine opening is tangible and easy to grasp. It’s the upstream segment of the mining value chain, where minerals are extracted. But dig deeper (pun intended), and you’ll find what happens after the ore comes out of the ground is just as important — maybe even more.

This is the oft-overlooked midstream stage known as mineral processing and refining — where, using some high science — raw rocks are transformed into the high-purity materials that (downstream) manufacturing industries actually need. And China has far more leverage than any other country in the world in this midstream segment.

Why is processing so crucial and challenging? For one, most critical minerals don’t come out of the earth ready to use. They are typically found mixed with other minerals or locked in ores at low concentrations. For example, in lithium ores, the valuable element might be just a tiny fraction of the ore, often bound up with lots of other “junk” which miners call gangue. Extracting that tiny bit requires a series of complex, multi-step procedures. And extracting the mineral is harder — and therefore costlier — if the ore is lower-grade.

Moreover, each mineral has its own stubborn quirks — some require high-temperature furnaces, while others need strong acids or solvents. All of them demand significant know-how, energy, and investment to get from rock to useful, higher-value material.

So, countries that lack refining capacity basically export the weighty low-value ore and buy back the high-value refined product. That’s not a great bargain. It proves that mining alone is not enough for true self-reliance.

A recent, vivid example is the status quo can be found in India itself. Earlier this year, it was reported that Jammu had unexplored lithium reserves. However, without local refining technology, that lithium would likely have to be sent abroad for processing before it can power an Indian-made battery.

Turning Vulnerability into Opportunity

In the past couple of years, a slew of policies have emerged as nations scramble to secure these supply chains.

The US, for example, passed the Inflation Reduction Act (2022), unlocking huge incentives for domestic critical mineral refining and recycling. Australia launched a “Future Made in Australia” plan with a $7 billion tax incentive to promote local processing and refining, plus funding for shared infrastructure. Japan rolled out subsidies covering half the cost of new smelting and refining facilities.

For all its progress, India today still finds itself heavily reliant on others for the minerals that its future industries will need. It imports virtually all of its lithium, cobalt, and nickel – metals indispensable for batteries and electronics. But what if India could turn this vulnerability into a strength?

But India isn’t sitting silently, either. In 2023, the government drew up a list of 30 critical minerals deemed essential to national goals. The decades-old mining law was amended to empower the central government to auction off blocks of these minerals more easily. In January 2025, India launched a comprehensive National Critical Mineral Mission, backed by a whopping ₹34,300 crore budget over seven years. One of its crucial pillars is to develop domestic processing capacity.

These new policies are creating momentum. As India identifies domestic deposits and even invests in overseas mines, a pipeline of raw materials could start to flow in the coming years. This also opens a window to build up processing and refining capacity in parallel, which can upgrade India from being merely a buyer in global supply chains to a competitive alternative supplier.

Encouragingly, India isn’t starting entirely from scratch here. We have decades of know-how in mining and metallurgy across a range of bulk metals like steel, aluminum, copper, and zinc. India is also one of the largest refiners of oil in the world — while having very little crude oil of our own. This existing expertise in handling large-scale mineral processing can be a headstart for tackling the more complex chemistry of critical minerals.

Where India stands today

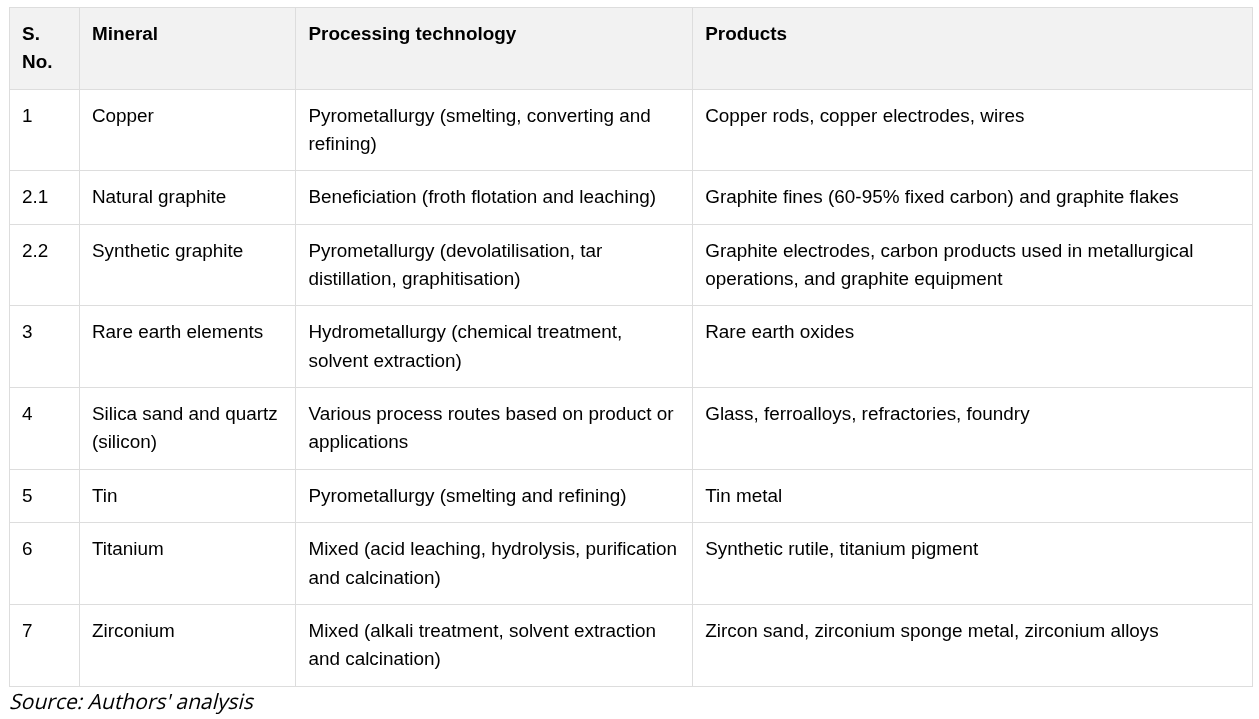

As per the CEEW, India currently has commercial-scale processing capability for only seven of them. These include familiar metals and minerals like copper, graphite, rare earth elements, silicon, tin, titanium, and zirconium.

In these cases, domestic companies do operate mines or refineries, which is good news. However, even for these seven, India’s capacity falls well short of domestic needs, especially when high purity is required. Technical constraints often prevent achieving the ultra-refined grades that cutting-edge technologies demand.

For instance, India processes rare earths from monazite sands, but fully separating all the individual rare earth elements at a purity required by batteries or magnet grades remains a challenge. Similarly, we produce some graphite, but not yet the super-pure spherical graphite needed for EV batteries at scale.

And then there are the critical minerals for which India currently has no meaningful production or processing. Chief among these are lithium, cobalt, and nickel – the trio powering lithium-ion batteries – where India relies almost entirely on imports today. In short, when it comes to the most vital ingredients of the 21st-century economy, India is still playing catch-up.

Why has India lagged behind?

The report points to several gaps in the domestic ecosystem that have held back critical mineral processing.

One major gap is limited technical know-how — refining lithium or cobalt is a different ballgame than refining iron or aluminum, and India simply hasn’t invested enough in the specialized R&D to master these processes yet. Moreover, weak links between research and industry do not help. While Indian labs and universities might experiment on a bench scale, too few of those innovations make it to commercial-scale operations.

Another big gap is the underutilisation of secondary sources. India generates plenty of industrial waste (like coal ash, steel slag, electronic scrap) that contain recoverable amounts of critical minerals. But we’ve barely developed a recycling ecosystem to do this.

Then there’s the shortage of a skilled workforce tuned to this niche sector – we need more metallurgists, chemical engineers, and technicians experienced in advanced refining techniques.

On the demand side, one could argue that historically, India’s domestic demand for certain high-tech materials was low. For instance, if you don’t make lithium batteries or EVs domestically in large numbers, there’s less incentive to refine lithium at home. But that equation is changing rapidly now with Make-in-India initiatives, the electric mobility boom on the horizon, and our rapidly-expanding solar capacity. This progress already justifies scaling up the processing industry.

What can we do about it?

So how can India bridge the gap between where it is and where it aspires to be in critical minerals processing? There is no one-size fits all solution. But the CEEW report lays out some practical, strategic suggestions.

For one, building a competitive processing industry starts with know-how. The report emphasizes investing in dedicated research for critical mineral extraction and refining technologies. Equally important is cultivating a skilled workforce, which will include specialized training, internships, and curricula focused on metallurgy for critical minerals.

The report also points out that by investing in technologies and facilities to reuse and recycle, India could cut import dependence while also addressing environmental waste concerns. It’s a win-win that also buffers against supply shocks, since above-ground “urban mines” are within our control.

Third, and probably most importantly, forging international collaborations is important, and we’ve already made a start. One example is a joint venture with Kazakhstan for titanium processing. Such partnerships can help India leapfrog by adopting proven technologies and processes, rather than reinventing the wheel. They also open doors to secure supply contracts – if India helps process a mineral, it is more likely to have assured access to that mineral. However, hoping for similar ventures with China might be more doubtful.

Conclusion

These suggestions aren’t an exhaustive list, but they sketch an encouraging path forward.

None of them are as simple as flipping a switch. Each requires concerted effort, investment, and coordination between government, industry, and research institutions. The tone of the recommendations is exploratory and practical, recognizing that India will need to experiment, adapt, and learn on the go.

What’s clear is that there’s no single silver bullet; instead, a combination of innovation (technological and policy), capacity building, and strategic partnerships will collectively move the needle.

Tidbits

SEBI has raised the minimum block deal size from ₹100 crore to ₹250 crore and widened the permissible price range to 3% above or below the stock’s price. The trades will continue through two sessions—morning and afternoon—and the revised framework will take effect 60 days after SEBI issues the circular.

Source: ReutersPVR INOX has launched its first dine-in cinema in Bengaluru as part of a push to boost non-ticket revenue and F&B spends. The format lets customers book tables instead of tickets, with dynamic pricing and plans for 4–5 more locations by FY27. The company is also expanding into catering, live events, and mall-based food courts through a JV with Devyani International.

Source: The Hindu Business LineHollywood and Bollywood groups, including the Motion Picture Association and the Producers Guild of India, are lobbying an Indian government panel to block AI firms from using films and videos for training without licences. They argue that broad AI exemptions would erode creators’ rights, while tech firms push for fair-use allowances to foster AI innovation.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

📚Join our book club

We’ve started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we’d love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉