SEBI unearths a ₹173 crore insider trading scam

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

SEBI unearths a ₹173 crore insider trading scam

Behind ASEAN’s ambitious power grid

SEBI unearths a ₹173 crore insider trading scam

Yesterday, SEBI passed an interim order against eight people for what it calls one of the most serious insider trading cases in recent memory. This one involved the Indian Energy Exchange (or IEX).

The story involves a government official who allegedly leaked confidential regulatory information to a former student, who then passed it to friends and family. Together, they made a whopping ₹173 crore by betting on IEX’s stock price crashing before the rest of the market knew what was coming.

Let’s dive into how this scam unraveled itself.

What is market coupling?

The story starts with a decision made by the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC). On July 23, CERC officially introduced something called “market coupling”, a change that would fundamentally alter how electricity is traded in India.

How does market coupling work? See, the IEX runs India’s biggest platform for short-term power trading, where electricity producers and buyers match bids for the next day. Under the old system, each exchange — IEX, PXIL, and HPX — discovered its own prices. Under market coupling, a single, central system would now set a uniform price across all exchanges.

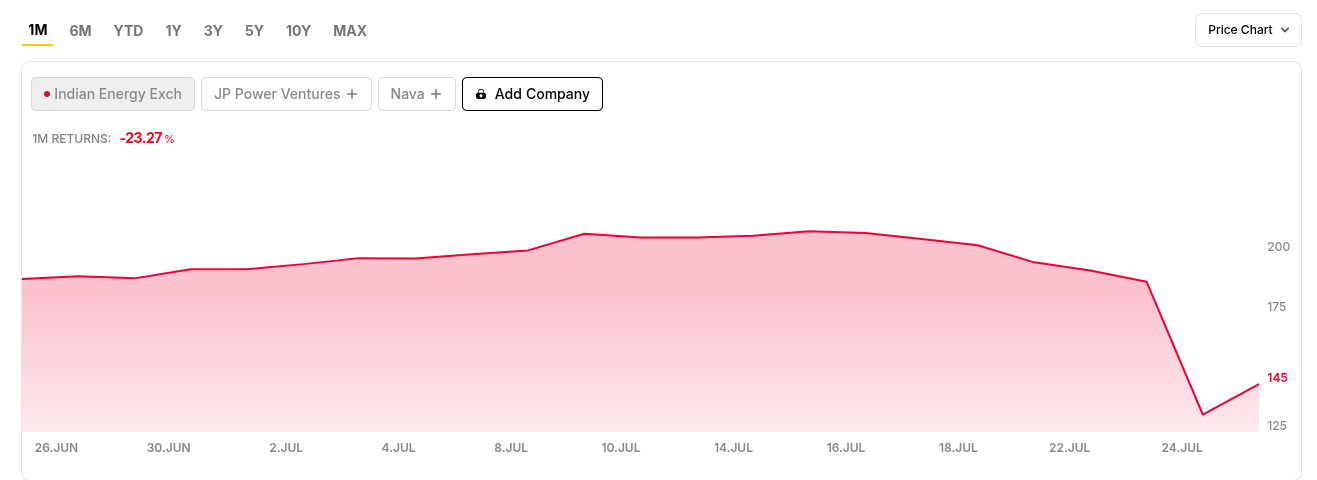

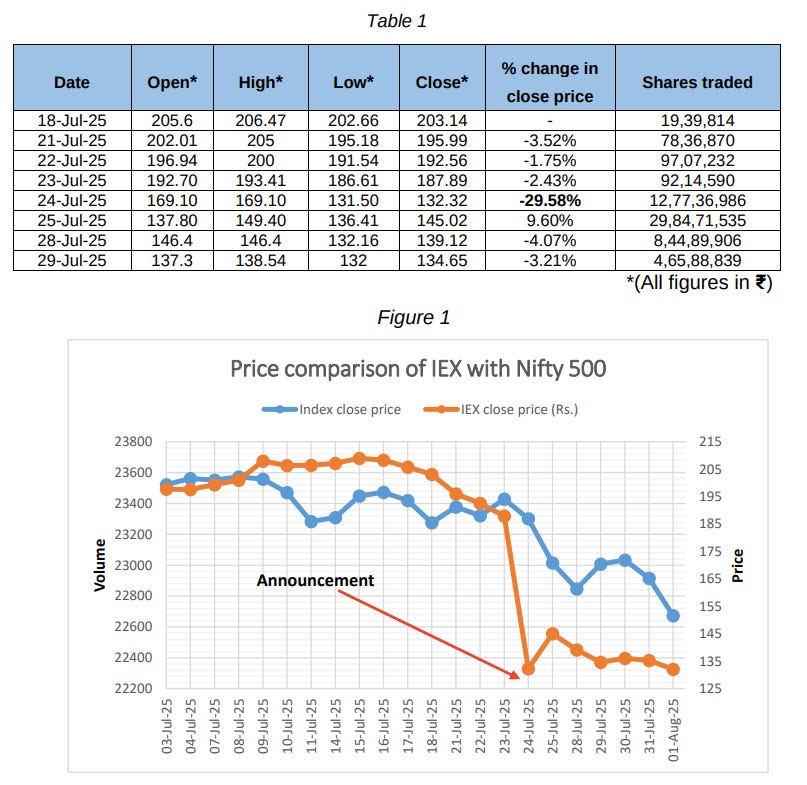

We’d covered this change earlier: especially how it could end IEX’s dominant role in price discovery, maybe even trim its margins. And investors knew this possibility. The next morning, IEX’s stock collapsed almost 30%, one of its steepest one-day falls ever.

The strange trades before the crash

However, when regulators looked back at the trading data from that fateful day, something didn’t add up.

A few days before CERC’s order, on July 21 and 22, there was a sudden burst of trading in IEX put options — a put option is a bet that a stock will fall. And as we know, with the CERC’s new order, the IEX’s dominance was about to decline. Those puts led to enormous profits when the order came into effect.

The pattern was way too clean to ignore: almost no trading in those contracts before, a huge spike ahead of the announcement, and then total silence after.

So, SEBI had to step in. Its surveillance systems had already picked up the strange movement. Around the same time, it also received a complaint pointing to possible insider trading here. So, SEBI immediately launched an investigation and began connecting all the dots to reveal the underbelly of this trade.

How SEBI began connecting the dots

Firstly, SEBI noticed that the same small set of names kept showing up across multiple trades. They weren’t regular derivatives traders. In fact, most of them had never traded a single IEX option of any kind before. Yet, in those two days before the order, they all suddenly piled into put options on IEX.

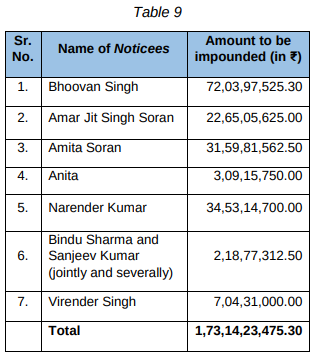

Their timing was impeccable. When the order came out on July 23, the stock fell sharply the next day. By July 28, they had closed out their positions, locking in massive profits. Bhoovan Singh, one of the traders, alone made about ₹72 crore; others made anywhere between ₹2 and ₹35 crore each.

In total, the group netted ₹173 crore in profits in just a few days.

But who were these people, and how did they know this was coming?

The key link, SEBI says, runs through Bhoovan Singh. He wasn’t an employee at IEX or a market insider in the traditional sense. However, his connection to the CERC was far more unusual — he knew a senior official at CERC, referred to in the order as “O1”. O1 wasn’t just your average bureaucrat. She was a Chief in CERC’s economics division, who was directly involved in drafting the market-coupling order. And interestingly, SEBI found out that Bhoovan Singh had once been her student.

That’s how this trail starts. A professor and her former student connected over WhatsApp, exchanging messages that contained sensitive regulatory information.

How the leak began

Inside CERC, discussions about market coupling had been going on for over a year. The commission had formed a committee to explore how to implement it. In their fourth meeting in Jan 2025, they finally produced a set of recommendations on how coupling could begin.

The leak started with internal documents from CERC’s economics division being shared with Bhoovan Singh on WhatsApp and email. On February 20, for instance, minutes of the January meeting were circulated inside CERC. On the same day, SEBI says, they were also forwarded to Bhoovan Singh, who then shared them in a WhatsApp group called “OTC”.

The group wasn’t made of CERC officials, but of the people involved in the trade. This group became SEBI’s biggest clue. Investigators found that Bhoovan had been sending messages there regularly, often relaying updates he received from O1 and another CERC official, referred to as “O2”.

Then, a fifth meeting on June 30, 2025 finalised the implementation plan. Those minutes were internal and they weren’t meant to be public until the formal order came out. However, by mid-July, history repeated itself. The minutes of the June meeting also surfaced in the same WhatsApp group.

But the rabbit hole doesn’t end here, either. On July 14, Bhoovan Singh told Sanjeev Kumar, a member of OTC, that the order could be out soon. The next day, Sanjeev showed up at CERC’s office. He was the managing director of a company called GNA Energy — itself a CERC-regulated entity. SEBI found that he met officials inside the office and even shared a photo in the group that showed a livestream of a CERC meeting.

By now, the group knew the timing. Between July 21 and 22, the trades began.

How the trades were placed

To buy the IEX put options, this group used different trading accounts spread across family members to spread out their exposure. Bhoovan had access to some of these accounts; in one case, Sanjeev placed trades using his wife Bindu Sharma’s account. These weren’t small-time retail bets, either; they were huge positions worth crores.

Bhoovan Singh was not at all a regular trader. SEBI examined his phone to find search histories that showed he had been looking up tutorials on how put options work, along with searches on how the CERC order could affect IEX’s stock. Clearly, the leader of this wolfpack didn’t know much about how the market worked, and had probably never placed a put option before in his life. But, he learned just in time to place the perfect bet.

When CERC’s market-coupling order went public on July 23 after market hours, the IEX stock plunged 29.6% the next day. The put options that cost just a few rupees suddenly exploded in value. By July 28, the traders had squared off, booking their profits.

What SEBI found during the searches

Once SEBI’s surveillance team spotted the pattern, it didn’t take long to move in.

Between September 18-20, it conducted search and seizure operations at the homes and offices of the suspects. Officers recovered laptops, phones, and confidential CERC documents that told the rest of the story.

Besides this, in Bhoovan Singh’s phone, SEBI’s forensic team also found traces of deleted WhatsApp and Signal chats with O1. After the trades, on July 31, the NSE sent queries to some of these traders asking for explanations about their sudden activity in IEX options. Right after that, SEBI says, the WhatsApp chats between Bhoovan and O1 disappeared. But the backups and Signal messages remained.

One of the surviving messages, sent on September 20 — 2 months after the trading — showed O1 forwarding a copy of IEX’s legal appeal to Bhoovan. Clearly, the guilty parties were still communicating after the trade — perhaps about how they could evade the law. This is another sign that they knew what they had done, and were trying to erase the trail.

SEBI also found bank transfers showing that part of the profits from these trades were moved into three connected companies which had overlapping ownership with the families involved.

SEBI’s interim action

On October 15, SEBI issued its interim order.

It froze a total of ₹173.14 crore, matching the alleged illegal profits, and restrained all eight people from trading in the market until further notice. The order directs them to park the frozen amount in fixed deposits under a lien to SEBI and to submit a full inventory of all their bank and demat accounts within 15 days.

SEBI also clarified that these findings are “prima facie”, meaning preliminary, and the accused can file their replies within twenty-one days and request a personal hearing. For now, the goal is to prevent the money from being moved or spent before the final decision is made.

The investigation isn’t over. The eight individuals have 21 days to respond to SEBI’s findings and can request a personal hearing. The regulator will continue examining digital evidence, financial trails, and any links to others who might have had access to CERC’s internal files.

Once that’s done, SEBI will issue a final order. If the violations are confirmed, it can impose penalties, order disgorgement of profits, or even permanently bar them from trading.

Behind ASEAN’s ambitious power grid

We often talk about international trade in goods and services. Whether it’s a net good or bad for the economy is up for debate. And Trump, for one, clearly thinks it’s bad for the U.S., hence all the tariffs.

But there’s something else that’s traded across borders which doesn’t feel very intuitive: electricity. Unlike electronics or crude oil, which can be shipped anywhere in the world through sea routes, electricity is bound by geography. You can only trade power through transmission lines. No transmission means no trade. Which means — an interconnected grid is everything.

India, unfortunately, doesn’t have the most cooperative neighbours for this. We don’t have many logical trading partners when it comes to electricity, and even with the few we’ve tried, it hasn’t exactly been smooth sailing.

Elsewhere though, this is a big deal. Europe is a giant interconnected grid, and that’s no small achievement. Building transmission infrastructure itself is a massive technical challenge, but getting so many countries to coordinate and run it smoothly is nothing short of remarkable.

Today, we’re talking about another, lesser-known multinational grid that’s closer to home: the ASEAN Power Grid. Conceptualized in 1997, it spent a long time stuck in limbo, but is now finally gathering pace.

This story is about what happened there — what went right, what went wrong, why getting such projects off the ground takes so much effort, and whether interconnected grids are actually worth all the effort. By the end, we’ll hopefully have learned a thing or two about power systems, a bit of geopolitics, and a lot about transmission.

Let’s dive in.

What Is the ASEAN Power Grid, and Why Does It Matter?

Imagine a giant electricity network stretching across Southeast Asia, seamlessly connecting all ten ASEAN countries. That’s the vision behind the ASEAN Power Grid (APG).

The idea dates back to the late 1990s, but progress was sluggish for decades. Now, however, this long-held dream is gathering momentum after years of inertia.

Why the renewed interest? One obvious, big reason is climate change. Southeast Asian (SEA) nations are looking for ways to cut carbon emissions and meet their climate pledges, and they’re realizing they can’t get there alone. In other words, countries like Singapore, Vietnam, or Indonesia will find it much easier to shift to clean energy if they can trade electricity with neighbors.

A shared regional grid would let a country with surplus renewable power (say, hydroelectric dams in Laos or wind farms in Vietnam) export it to places facing power deficits, and vice versa. In fact, as per some expert estimates, better regional power integration could slash the cost of decarbonization by about $800 billion (11%) compared to each country going it alone.

Beyond climate concerns, practical economics are also at play. For one, SEA’s power demand is soaring; the region is on track to see one of the fastest electricity consumption growth rates in the world over the next decade. At the same time, their governments are under pressure to keep energy affordable and reliable.

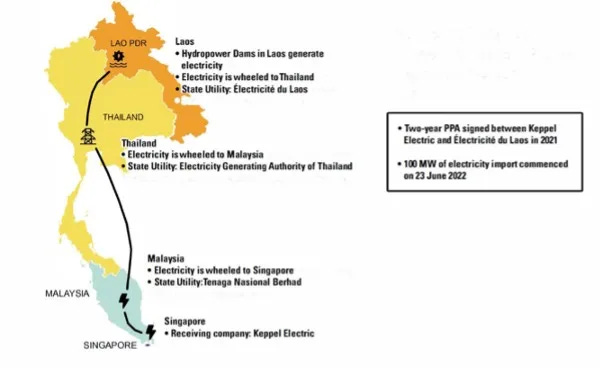

Additionally, a regional grid can resolve demand-supply mismatches. Laos, for instance, has an abundant supply of hydropower that it can’t fully consume itself. On the other hand, Singapore is trying to decarbonize itself, but doesn’t have enough land to install large solar farms or hydroelectric dams, and has always been reliant on imports for its own power needs. An ASEAN grid would solve both of their problems.

A unified grid potentially promises cheaper, more secure power for nearly 68 crore people. Instead of each nation building expensive backup power plants or suffering blackouts, they could buy electricity from a neighbor through the grid when needed. This kind of cross-border trading could lower overall generation costs and reduce reliance on polluting fossil fuels. A more integrated ASEAN grid might even trim consumer electricity prices by up to 3.9% across the region — a win-win for wallets and the environment.

What’s Actually Included in This Grid?

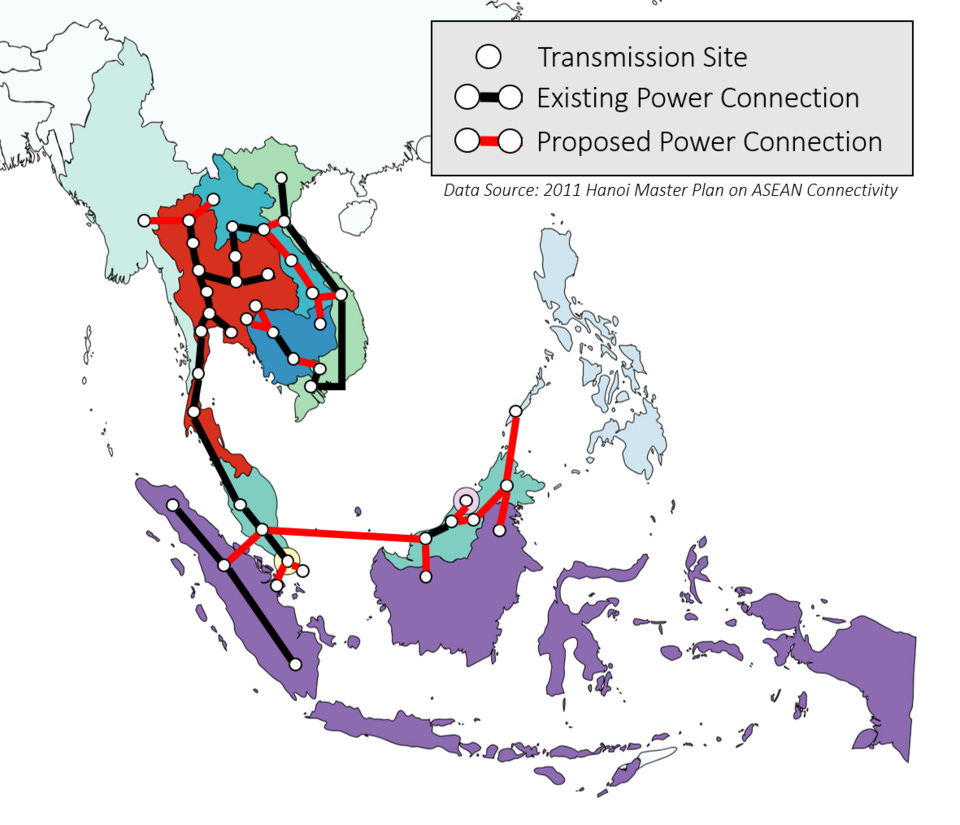

So, what does a “regional power grid” look like in practice? Rather than one physical mega-grid being built overnight, the ASEAN Power Grid is coming together through dozens of cross-border links and trading arrangements, piece by piece.

Think of it as connecting the dots: first between two neighboring countries, then gradually expanding those links into a wider network that spans the whole region. The ultimate goal is a fully integrated, Europe-style power system by 2045, where electricity flows freely across borders as needed. But getting there is a phased journey.

The first phase is bilateral connections — building grid interconnectors between two countries. Many such links already exist: Malaysia and Thailand’s grids are linked at their border, as are Thailand and Laos, Laos and Vietnam, and so on. These lines allow one country to directly buy power from another. For example, Thailand generally imports electricity from hydroelectric dams in Laos via dedicated transmission lines. These one-to-one deals prove that cross-border trade is feasible technically and commercially.

The second phase is multilateral trading projects. The next step is linking multiple countries in a single power exchange agreement, essentially expanding from bilateral to small multilateral pilots.

The most notable breakthrough here is the Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project (or LTMS-PIP). It works like this: Laos generates hydropower and sends it into Thailand’s grid; from Thailand the power flows to Malaysia, and ultimately into Singapore. This makes LTMS-PIP a proof of concept that multiple ASEAN countries can coordinate to buy and sell electricity as a group. However, it’s worth noting that currently it’s still a relatively small, one-directional deal largely relying on existing bilateral connections.

Another ambitious multilateral initiative on the drawing board is the Brunei-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines Power Integration Project (or BIMP-PIP). This one aims to connect the power grids across countries with lots of islands and sea between them. Unlike the land-based links of mainland SEA, the BIMP-PIP will require undersea cables to hop between islands. The vision is for two-way flows of clean energy but it’s a far more complex undertaking than LTMS-PIP, both technically and financially.

The third phase will aim at creating one unified grid. In the long run, by the 2040s, ASEAN’s goal is to weave these bilateral and multilateral links into a fully integrated regional grid with an open electricity market. In practical terms, this could mean a future where, say, a surplus of midday solar power in Indonesia could instantly be sent to help power factories in Thailand. Or, a wind farm in Vietnam could ramp up output to keep Singapore’s data centers running after dark. That is the endgame.

So what’s the holdup?

If the ASEAN Power Grid sounds so great on paper and is the need of the hour you might wonder why it isn’t already a done deal. The truth is, building an integrated regional grid is hard, for a mix of technical, financial, market, and political reasons. Here’s a breakdown of the key challenges holding the project back:

Technical challenges

It’s tough to synchronize electricity systems across ten different countries. Power grids need common standards and grid codes to operate in unison, which ASEAN currently lacks.

Let’s understand it with an example. India and EU operate their grids at 50 Hz frequency. However, India’s grid often fluctuates around 49.5–50.5 Hz. The EU grid is kept extremely tight: usually between 49.95 and 50.05 Hz. These tiny differences matter. Cross-border links need both sides to stay stable; otherwise, power can trip or destabilize the network.

There’s also the basic issue of reliability: if one country’s grid experiences a blackout, how do you prevent that from cascading to neighbors through the interconnections? This is something that actually happened to Spain this year because of a fault in an interconnection line with France. These technical hurdles mean progress has been cautious and countries are careful about hooking up to a neighbor’s grid if it could introduce instability to their own network.

Financial costs

Building an ASEAN-wide power grid is an expensive proposition. We’re talking hundreds of billions of dollars in new infrastructure, like high-voltage transmission lines, subsea cables, substations, and so on. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates the region will need to invest at least $100 billion by 2045 just on cross-border transmission lines. ASEAN officials have put the total price tag for the full grid vision as high as $764 billion.

The ADB and World Bank recently launched an ASEAN Power Grid Financing Initiative with the ADB committing $10 billion to kickstart projects, but that’s just a fraction of what’s needed. Private investors are afraid of putting money into giant transmission projects unless they’re confident they’ll get paid back, which requires stable agreements between countries.

The cost challenge is especially high for the island connections: linking, say, the Philippines or Indonesia’s archipelago to the mainland grid means laying very long, very high-capacity cables under the sea. That’s vastly more expensive than building overland lines.

Market mismatches

Even if the physical wires are in place, you need compatible market rules to trade electricity smoothly. Here, ASEAN’s diversity becomes an obstacle.

Some member states, like Singapore, have liberalized electricity markets – multiple power generators compete and trade on a wholesale market, and prices fluctuate with supply and demand. Others, like Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand, still use a “single-buyer” model where a state-owned utility company controls all power purchases and sales, somewhat like India.

These different market structures make regional trading tricky. For instance, Singapore might want to buy power in real-time from whoever offers the best price. But if Laos on the other end has only one state utility that sells at a fixed price under long-term contracts, how do you reconcile that? Each country has its own laws on energy imports/exports, tariffs, and monopolies. Harmonizing these rules or creating a regional marketplace for electricity is a slow process.

Political Will

To be fair, the technology exists, the capital can be raised, and markets can be designed. All of it becomes possible if there is enough political will. Energy policy touches on national sovereignty – governments can be uncomfortable about depending on neighbors for something as critical as electricity.

In ASEAN, decision-making is consensus-driven and member states guard their autonomy closely. Getting all 10 countries to agree on bold, long-term infrastructure sharing is not easy. Some countries forged ahead on bilateral deals that suited them, but there wasn’t always a collective drive to push the regional project as a top priority.

In short, technical, financial, market, and political issues have all conspired to keep the ASEAN Power Grid progressing slower than hoped. As of now, only about half of the 18 originally planned interconnection projects have been completed, and most of those are just basic two-country links. The fully integrated grid is still a long way off.

Conclusion

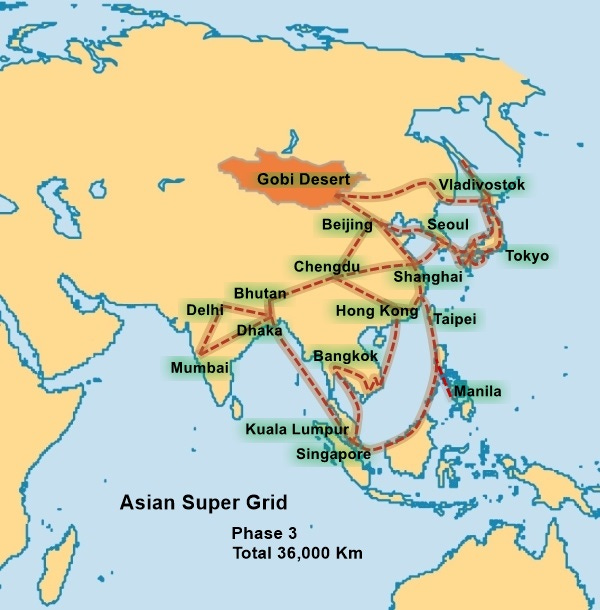

A fully connected ASEAN Power Grid could be transformative, cutting fossil fuel reliance, lowering energy costs, and boosting the region’s competitiveness. It would let renewable power flow across borders to where it’s needed, creating a more secure and efficient energy system. Beyond ASEAN, it could eventually anchor an “Asian supergrid” linking India, China, and beyond — a distant but powerful vision.

If countries align, this grid won’t only be a success story for renewable energy. It could actually light the way for a new model of cooperation between countries in today’s tense times.

Tidbits

India’s palm oil imports fell 16% in September to a four-month low as refiners switched to cheaper soyoil, whose imports hit their highest since 2022. In an earlier episode, we covered the trade chaos of our cooking oil.

Source: Reuters

Just a few days back, we spoke about coking coal — now, India’s steel mills are facing a met coke crunch, meeting barely half their needs in the first half of 2025. Producers like JSW and ArcelorMittal are urging the government to ease import curbs that have tightened supplies.

Source: Reuters

Hyundai Motor will invest ₹45,000 crore in India over five years, with 26 product launches including seven new models and its first locally made electric SUV by 2027. The company aims to make India a global export hub, crossing ₹1 trillion in revenue by FY30.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

📚Join our book club

We’ve started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we’d love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉