SEBI skins a notorious finfluencer

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

SEBI skins a notorious finfluencer

Don’t fear the exchange rate

SEBI skins a notorious finfluencer

Have you seen The Wolf of Wall Street?

If you don’t know already, the movie is about a trader named Jordan Belfort (played by Leonardo DiCaprio). He recruited many unknowing people — who knew nothing about the stock market — to sell scammy stocks to unsuspecting retail investors. In that process, he built a cult of personality around himself, where he promised people to make people rich beyond their wildest dreams. And they took his word as gospel.

But most of those promises were false — he got jailed for stock manipulation and misselling.

India has similar (if not same) cases, too, like Ketan Parekh and Harshad Mehta. And SEBI is always on a tight watch for such individuals.

They’ve now trained their sights on Avadhut Sathe, a self-proclaimed finance professional who sold stock market education courses. He built a cult around himself, with people claiming their fortunes have changed because of his courses.

His case is not as serious as the scams mentioned above, which were hard-core stock manipulation cases rather than miseducation. But the cult of personality is common to them. And, much like Jordan Belfort, there’s a lot of dancing in his events. Almost as if they’re weddings rather than conferences.

Dance Video Of Avadhut Sathe Sir #shortvideo #dancevideo - YouTube

But here’s the thing: in the stock market, you should be deeply suspicious of such promises and cults. No one — not even the best investors — has a one-size-fits-all magic formula to beat the market consistently and be foolproof. However, much like godmen, Sathe offered such magic.

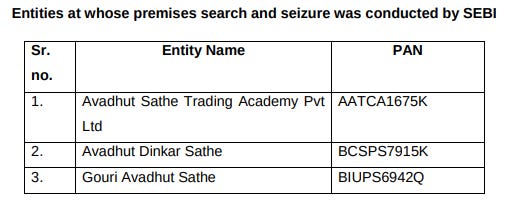

So, SEBI has taken Avadhut Sathe, and his wife Gouri Sathe — the directors of Avadhut Sathe Trading Academy (or ASTA) — to task, raiding their property earlier this year. We’ll break down what they found, but more than the dissection of a potential case of fraud, this is a cautionary tale.

Let’s dive in.

The cost of no registration

Avadhut Sathe’s scheme boils down to one thing: that he was unregistered with SEBI.

See, in order to provide investment advice or even publish official equity research, you must register yourself with SEBI. It’s not a very expensive process. You just need to meet certain educational qualifications, pass an exam by the NISM, and meet a minimum level of work experience.

But, it’s the rules that apply after registration that matter most. After all, you’re now a custodian of the Indian capital markets, and your word matters to the rest of the market. That means you can’t mislead people, or run unofficial channels to peddle investment advice.

For this reason, there’s a list of things SEBI-registered investment or research analysts cannot do. That includes running WhatsApp (or Telegram) stock tip groups, or guaranteeing success or any type, or advertising selective success stories. Analysts can sell educational courses, but they cannot be mixed with specific stock recommendations.

However, ASTA was basically found to break each one of these rules. In fact, one might say that being unregistered with the SEBI was the foundation of its “business model”.

We don’t need no education

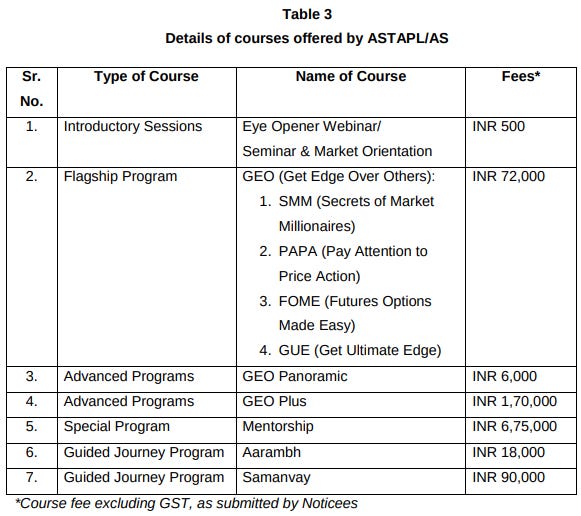

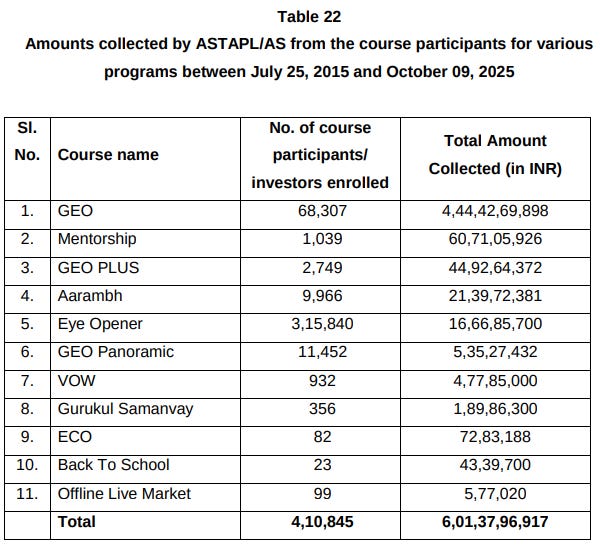

At the heart of ASTA’s business are multiple-tier courses on how to play the stock market. Many of them have extremely cheesy names.

The courses broke every rule in the book, and here’s how.

To start with, SEBI seized video recordings of the courses in the raid. Across every course, Sathe (or one of the other teachers) explained an entire trade: from the stock choice, to when and what price to buy, all in real time. A huge no-no in the eyes of SEBI, which does not allow live-trading sessions in educational courses.

It gets worse, though. Sathe was also found making stock market predictions in his courses — and if there’s anything we know about predictions, it’s that they’re more often wrong than not. To do so in an attempt to influence your own students to trade, especially as an unverified investment advisor, is an extremely shady practice.

In fact, Sathe was explicit in his influence, often saying that his trades are “good for everyone”. SEBI also found him showing his own mark-to-market gains to try and get his students to make those trades.

And that influence worked just as intended. SEBI has also found evidence of the participants duplicating Sathe’s exact trade at the same time as him.

These offences are bad enough as it is, and it looks like it couldn’t get much worse. But the outcomes of these trades are where this crosses over from mere rule-trespassing to a potential case of fraud.

No money where the mouth is

ASTA has been aggressive in promoting its courses. The most important marketing device it used was testimonials from past students, who would credit the supernormal returns they earned to Avadhut Sathe’s courses. These students were either homemakers, bankers, people who worked regular jobs.

Doesn’t this seem like the easiest way to earn trust? Only if you judged a book by the cover. SEBI found that, in the case of 5 public testimonials available on YouTube, the actual profit earned by the student was far less than advertised. Actually, of the 5 people, only one had recorded a profit. All the rest bled lakhs of losses in the time period advertised in the testimonial. This is as obvious and blatant as fraudulent advertising can get.

If you zoom out from these testimonials, it becomes clear that Avadhut Sathe has no magic formula for beating the market. For 186 ex-students, SEBI found that in the 6 months after the course completion, 65% of them incurred losses. In total, this entire set of 186 people made a dismal loss of ~₹1.9 crore.

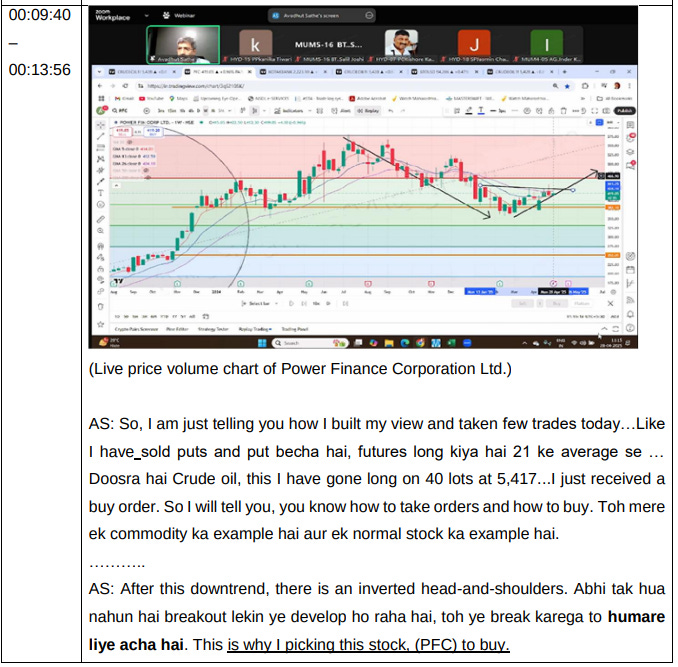

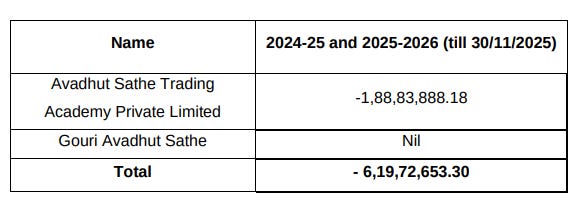

What’s even more damning is that, if the last 2 years are anything to go by, Avadhut Sathe himself wasn’t great at trading. SEBI discovered a cumulative loss of over ₹4 crores in his trading account, while his trading academy also ran a loss of ~₹2 crore.

But these losses were more than made up with the total course fees collected over the last 10 years. They served over 4.1 lakh participants who paid them a total of ₹601 crore. In the end, they did win, but at the cost of their students.

Now, some of this is already known. In fact, nearly 2 years ago, based on some preliminary findings, SEBI issued an early warning to Avadhut Sathe to stop misrepresenting things.

However, Avadhut Sathe, with his infallible cult, responded with how he’s being unfairly targeted. He argued that he could not be classified as a finfluencer because he did not monetize his YouTube or social-media channels. He conveniently called himself a “victim of regulatory vacuum”.

Well, with the new information that has come to light, it seems more like a case of “it isn’t cheating until you get caught”. And this order could potentially set a precedent for those who run similar unregistered advisory operations.

The penalty

SEBI’s order is not final. It doesn’t have too many binding directives, and Sathe hasn’t yet been legally charged with a crime. But even by those measures, it is strict.

SEBI has banned Avadhut Sathe and his wife from dealing in securities in an individual capacity. They are also not allowed to sell off any of their assets in the meantime. Most importantly, SEBI has impounded over ₹546 crores from ASTA, deeming it as unlawful gains received from selling unregistered investment advice. Now, they’ve not been fully seized, but they’re just one step away from there. This money will be put in a fixed deposit account that will be under the watchful eye of SEBI.

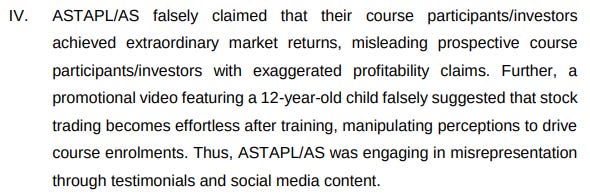

Since this is an interim order, things could get far worse from here. In fact, the interim order has some complaints for which concrete evidence hasn’t been found. One such complaint is that ASTA used a 12-year old in a promotion video, perhaps to showcase that if a 12-year old can effortlessly trade after a course, so can you.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, the stock market is a game where you deal with the fact that you can never know the future for sure. Risk lurks in even the simplest-looking trades, and it is always worth being skeptical of those who claim that they’ve 100% mastered risk.

Once in a while, capital markets keep getting such figures. Usually, their story is all too common: have a lot of innocent people believe your supposedly-godlike power, behind which are highly-suspect practices. These practices stack on top of each other, but such a stack becomes too visible for a regulator to not ignore. And that’s when the house of cards begins to crash.

Much like Wolf of Wall Street, which made us laugh a lot, the ASTA incident has left some funny tidbits — like this jingle.

But jokes aside, we’d like to restate the importance of investor awareness in light of such incidents. If you want to learn about trading or investing, you can check out Varsity Live, where we teach everything for free, without any song and dance.

Don’t fear the exchange rate

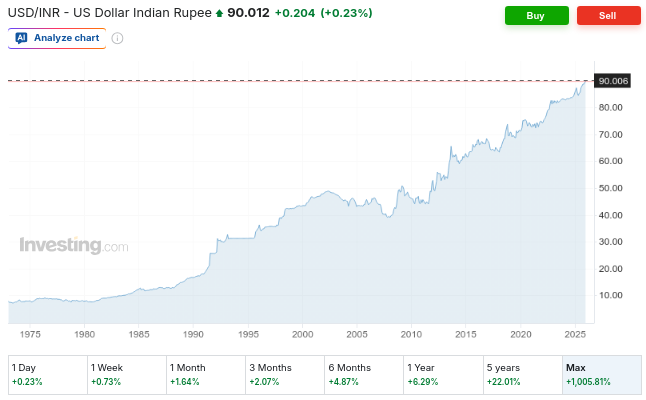

You’ve probably seen a lot of articles, recently, on how the USD-INR exchange rate crossed the ₹90 mark. Some breathlessly call this a crisis. It is not. That figure is considered a “psychological barrier”, but that’s only because it’s a nice, round figure. Ultimately, though, it’s a number like any other.

You should understand what’s happening, however, and why that number always seems to rise.

Currency economics tends to sound very complex. At a broad level, though, it boils down to just two simple things: supply and demand.

Every time any money leaves India, at an abstract level, it creates a supply of Rupees in currency markets. Likewise, every time money enters India, someone demands Rupees from currency markets, to send into India. The specific mechanism through which these forces play out can be complex. But fundamentally, these two forces alone determine the exchange rate.

If there are too many Rupees floating around international forex markets, without someone having a real need for them, supply exceeds demand. The “value” of the Rupee falls. Likewise, if a lot of people are hunting for Rupees to pay someone in India, but there isn’t enough of it on international markets, demand exceeds supply. The “value” of the Rupee rises.

However, to really understand the dynamics driving demand and supply, we’ll need to dive a little deeper. For that, we’re looking at an excellent summary of the current situation from MUFG.

Current account

One way of tracking all these flows of money is a country’s “balance of payments”. Think of it as a giant diary that records all the money that’s moving in and out of a country, for whatever reason.

Not all these flows behave the same way. Sometimes, you send money across borders without any future expectations or strings attached. These are simple payments, made for whatever reason — from payments for something you’ve bought, to even scholarships or charitable donations. Crucially, these do not create any assets of future obligations.

This is the realm of the “current account”.

The demand-supply question

The current account is the simplest, most direct place to see the demand and supply of the Rupee.

On the one hand, there are many things India buys from the world — like oil, gold, iron, laptops, even subscriptions for services like ChatGPT. Every time an Indian makes such a purchase, they introduce Rupees to the currency markets, creating more supply.

At the same time, we sell things to the world — like carpets, spices, medicines, iPhones lately, IT services and so on. Every time somebody pays an Indian, they create demand for Rupees in the currency markets to make those payments.

There are other, smaller flows, too. Like an interest payment made by an Indian company for a loan taken aboard. Or when an NRI sends money back home from California. And so on.

The variables at play

There’s a simple way to understand India’s long-term current account trajectory: as a share of our GDP, our imports are regularly 2-3% higher than our exports. This difference creates a steady “current account deficit” — that is, every year, Indians pay out a little more money than they bring in. The supply of the Rupee, then, constantly outstrips demand.

This has recently become slightly more complex.

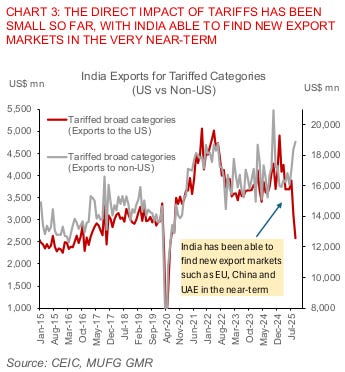

For one, Trump slapped massive tariffs on Indian imports. As we wrote before, this has been terrible for some pockets of our economy — like textiles, or jewellery. Of course, India’s exporters aren’t sitting idle; they’ve found new markets to replace the US, and are ramping up our exports there. But it’s not easy to replace one’s largest trading partner.

In the aggregate, therefore, people from abroad are buying slightly fewer things than usual from India, and are sending less money our way. The demand for the Rupee has fallen.

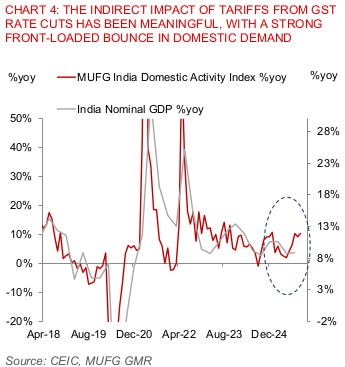

On the other side of the equation, the government just cut GST rates, and Indians responded by making a lot of purchases. Some of those purchases were imported. Many others — such as automobiles — were probably made in India, but using imported parts. In both cases, some money left India.

Our biggest surge in imports, perhaps, was of gold. As we’ve written before, this festive season, Indians shook off the shock of high gold prices, accepted them as the new normal, and bought jewellery with the same vigour as ever.

In short, Indians have been sending a lot of money abroad. The supply of Rupees has grown. And with it, the difference between supply and demand has grown too.

Capital account

There’s another facet to a country’s balance of payments. Sometimes, money comes into our borders, but with an obligation attached. It could be to purchase an asset — for instance, a foreigner buying a flat in an Indian society. That money could create some other sort of claim, like money that a foreign bank has loaned to an Indian, expecting that it’ll be paid back. This is money that comes in, but it isn’t something we can take for granted — the person sending money into India either gets to own something in return, or expects to be paid back later.

If our current account, alone, determined our exchange rate, our deficit would have disappeared a long time ago. After all, if more payments constantly leave the country than come in, to anyone outside India, Rupees keep becoming less useful. That should pull its value down. And our money becomes less valuable, it’s much harder for us to buy things from abroad, while outsiders get a “discount” on anything they buy from India. In theory, then, the imbalance between our imports and exports should quickly evaporate.

A big reason that hasn’t happened — and the reason we’re constantly able to make those extra purchases — is all the money flowing into our capital account.

Long-term investments

Any investor putting money into India, in a broad sense, creates demand for Rupees in currency markets — which are then invested into the country.

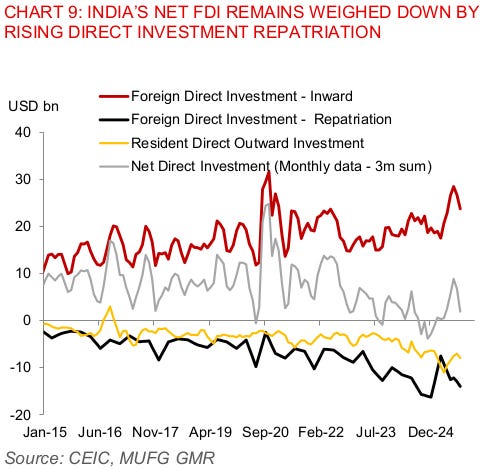

For decades now, India has regularly drawn a lot of investment from foreign countries. This has created a constant source of demand for the Rupee. Off late, though, there’s a steady stream of supply to balance this out.

This is the outcome of two trends. One, foreign investors are cashing out on their investments. Every time a large foreign PE fund sells their shares in an IPO, for instance, they take Rupees from investors and introduce them into currency markets. Now, this isn’t a bad thing — foreign investment only comes into India because people hope to eventually make a profit. If nobody could cash out, nobody would invest either. But temporarily, that adds to the supply of Rupees.

Two, as we’ve occasionally covered, Indians are making more foreign investments than ever. Again, this isn’t a bad thing. A successful foreign investment only enriches India — both, by bringing in returns, and by introducing us to new ideas and know-how. But this, too, adds to the international supply of Rupees.

Net-net, these two trends have resulted in a slight decline in investors’ demand for Rupees. For brief periods, in fact, this supply even outstripped demand — pushing the Rupee down rather than propping it up.

Betting on India’s markets

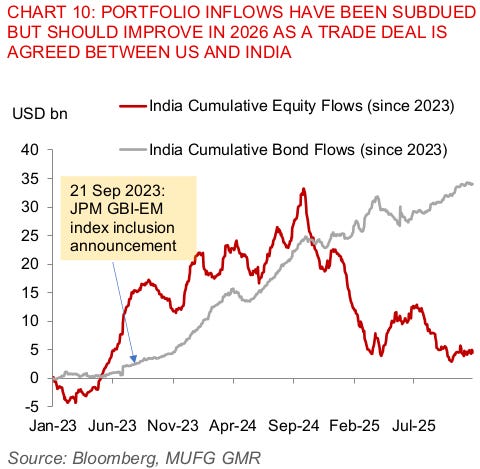

Sometimes, foreign investors don’t actually want a long-term bet on a specific Indian business or asset. Sometimes, they’re simply taking bets on India’s financial markets — in all the stocks, bonds, mutual funds and derivatives we have to offer.

These are called “foreign portfolio investments”, and they come in all forms. They could look like the exciting high-wire maneuvers by hedge funds like Jane Street. But these could also just be boring foreign funds parking their money in a basket of debt securities.

The principles stay the same, though. When they put money into India, they create demand for the Rupee. When they pull out — which is much easier when you’re only dealing with financial markets — they create supply.

Late in 2023, Indian bonds were added into JP Morgan’s index of government bonds from emerging markets. This brought a rush of foreign portfolio money into India. Over the last year, though, foreign investors have been scared away from Indian equities. There have been many points where foreign equity investors have sold their holdings much faster than foreign debt investors have acquired them. This could be for many reasons — including the simple fact that investors across the world are terrified by the world’s current trajectory, and are taking less risk than before.

Either way, currently, Indian equity markets don’t have a lot of interest from foreign portfolio investors. That has suppressed what is otherwise a massive engine of demand for the Rupee.

Confounding factors: central banks, liquidity, and more

Let’s put this all together.

There’s a constant outflow of money from India, because our imports and exports aren’t perfectly balanced. With tariffs on one end and GST cuts on the other, that skew has only grown in the recent past. Ideally, this would be balanced with capital flows coming into the country. Right now, however, people are cashing out of their Indian investments, or are investing abroad. And portfolio investors are cooling on Indian equities.

The result? For now, Rupee supply, internationally, is higher than its demand. Naturally, the Rupee has fallen.

That’s the heart of what’s driving our exchange rate. There are a few things that can skew things a little, though:

Like anywhere else in finance, there are many other reasons that people approach a currency market — from hedging their exposure to foreign currencies, to simply taking bets on where things might go next. This skews the simple demand-and-supply picture we’ve painted.

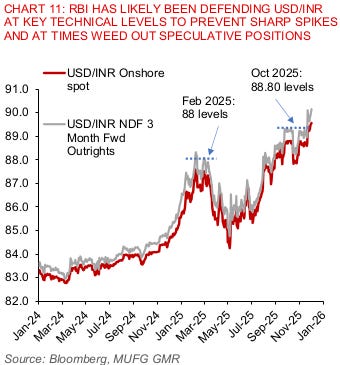

The RBI is the biggest whale in international Rupee trading. It can single-handedly move the market. When there’s a lot of international interest in the Rupee, it tends to hoard foreign exchange as “reserves”. Later, when the Rupee is under pressure, it dumps those reserves to buy Rupees — creating a flood of fresh demand. The RBI lets the Rupee move along with the market, but in a slow crawl.

A lot of the Rupee’s attractiveness comes from the repo rate the RBI sets. The higher rates are, the better returns you’re likely to get on any Rupee-denominated asset — and the more it’s in demand. The RBI’s recent rate cut, for instance, could make the Rupee slightly less attractive to hold — putting further downward pressure on its price.

The liquidity in our banking system, meanwhile, shapes how easy it is to sell or borrow Rupees. A more liquid Rupee is a Rupee in high supply, and that can erode its value.

What you should expect

It doesn’t look like the Rupee will recover soon.

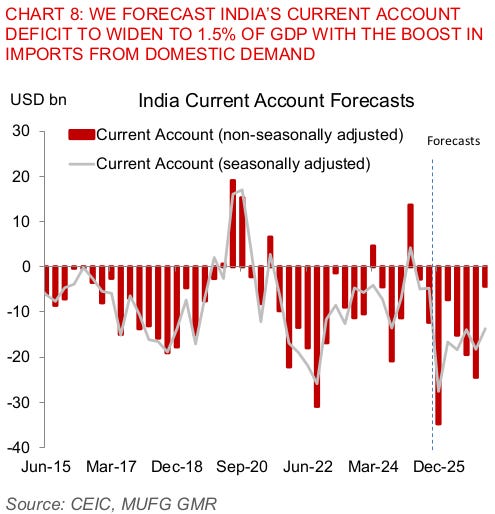

If MUFG is to be believed, given the GDP cuts, Indians are in no mood to pause their buying spree. By its forecasts, our current account deficit will probably widen in coming months — even assuming that the US will soon cut tariffs on our exports.

Investors, meanwhile, don’t seem to be warming up on India any time soon. With the most recent rate cut, the Rupee could become less attractive.

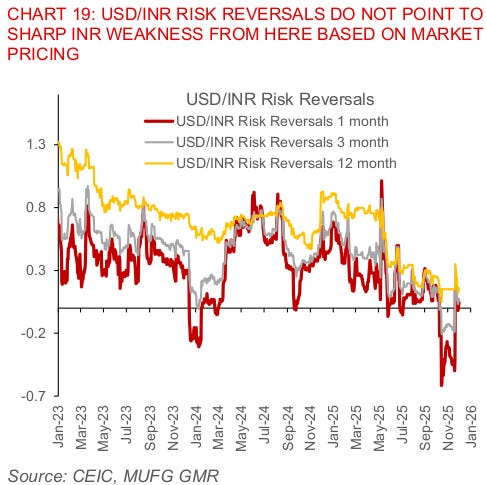

But there are signs to be hopeful. For one, the markets aren’t freaking out. If anything, they’re rather sanguine about what’s happening.

If anything, the Rupee looks unusually cheap when compared to other international currencies — a sign that it might re-gain some strength over time.

More importantly, though, short-term price fluctuations are just noise. The bigger question is: how do the fundamentals of the Rupee look. There, there’s distinct good news. The world’s recent volatility has pushed our government into action, and it has unleashed wide-reaching reforms to everything from labour markets to import restrictions.

And since the Rupee seems to have fairly-solid foundations, the fact that we’ve crossed the ₹90 threshold shouldn’t bother you.

Tidbits

Reliance starts work on Jio IPO draft

Reliance has begun preparing the draft prospectus for a long-awaited Jio Platforms IPO, Bloomberg reports. The listing is expected to be India’s biggest ever, though timelines remain open. Work has started quietly as markets turn more favourable for large tech floats.

Source: Reuters

Meta to cut Metaverse budget by 30%; layoffs likely

Meta plans to slash next year’s Metaverse/Reality Labs budget by 30%, with layoffs possible as early as January. Most cuts will hit VR and Horizon Worlds, despite earlier optimism from leadership. Reality Labs has already racked up $70+ billion in losses, and investors want Zuckerberg to redirect cash toward AI.

Source: Economic Times

Adani, Hindalco eye Peru copper mines

Adani and Hindalco are evaluating the purchase of Peruvian copper assets as global demand surges with the clean-energy transition. India’s copper needs are set to triple by 2030, and both groups are scouting overseas mines to secure long-term supply.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

enjoyed the second story a lot!

Great article team....