Of repo rates, black boxes and balance sheets

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why Repo Rate matters

The Economics of Air Pollution

Why Repo Rate matters

Everyone knows that if you’re a “finance-type”, you’re supposed to care about the RBI’s repo rate. Whenever its monetary policy committee discusses the topic, financial papers dissect every little syllable, while economists write up huge, graph-laden reports. But what does that number actually do?

Empirically, we know that it matters. According to studies by the RBI, every time it cuts its rates by 1%, there’s an instant 0.09% jump in investment in the economy. Over the long term, that bump in investment grows to ~1.09%.

Why does an arbitrary number set by the RBI change our economy so much, though? We’ve told you before about the “interest rate channel” — about how the repo rate finds its way into the loans that businesses and people pay. But that’s not the only way the repo rate affects the economy.

The truth is, we have many different, overlapping explanations for what’s happening under the hood. Monetary policy works in many ways. At different times, there are different channels through which it affects the economy.

One of those is the “balance sheet channel” — where rate changes directly affect a company’s financial health. That’s the subject of an interesting new paper by the RBI.

Let’s dive in!

What in the world is the “balance sheet channel”?

There’s an obvious way in which the RBI’s repo rate affects a company. As the repo rate climbs, interest rates rise (we’ve detailed this out before). When that happens, it becomes more expensive for companies to borrow, making them hold off on loans.

This is a big part of the story. But there are more subtle factors at play.

Imagine you ran a business, and were wondering whether to take a loan. Overall, financial conditions were getting tighter across the economy. Somehow, though, someone was offering you a loan at exactly the same interest rate as they did before. Would your borrowing behaviour stay unchanged?

Remarkably, the answer is no.

The interest rate isn’t the only thing you would consider while taking a loan. There would be more nuance to what you do. While, on one hand, you would be interested in how your borrowing costs move, you would also keep an eye on the assets you already have. If the value of your assets — your land, your inventory, your investments, and more — were to fall, the very same loan would feel more expensive.

Interestingly, repo rates can make your assets shrink.

A couple of decades ago, the economists Ben Bernanke and Mark Gertler wrote a series of papers, arguing that the way monetary policy works is, really, a blackc box. Monetary policy shifts many levers at once.

Of course, when monetary policy tightens, the cost of borrowing goes up.

That doesn’t happen in isolation, however. The repo rate simultaneously changes the price of everything. The repo rate, in a sense, sets the price of money. If the price of money goes up or down, the price of everything moves with it, including all of a company’s assets. When monetary policy tightens, a company’s market capitalisation falls. The price of each share drops. All its properties become cheaper. Its investments go down in value. That is, the entirety of a company’s balance sheet shrinks. Its net worth drops.

For one, this spooks companies. If what they own is worth less, they’re less willing to borrow. A loan that made sense before looks much less attractive as your balance sheet shrinks.

At the same time, banks start looking at companies differently. A company might own exactly the same things as before, but if its net worth falls, it looks like a less attractive borrower. Banks then demand a higher risk premium for the very same loan.

Put this all together and you see a nuanced picture emerge: when the repo rate rises, a company’s cost of borrowing goes up for many reasons. Banks charge higher in general, but also, the very same companies seem like riskier borrowers. Meanwhile, companies become more circumspect about borrowing. Together, these create an “external finance premium” — making borrowing look less attractive.

People have empirically studied these complexities all over the world — from the United States, to Japan, to Eastern Europe. In India, however, researchers haven’t explored this dynamic as deeply. That is the gap the RBI was trying to fill.

What the RBI studied

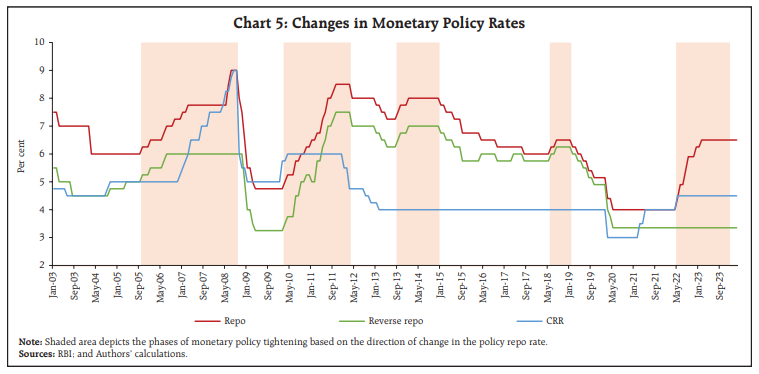

The RBI looked at almost 800 Indian manufacturing companies, through the years between 2002-2003 and 2022-23. In those two decades, India saw five different phases in which monetary policy became tighter. Studying them, the RBI asked: how do companies behave as the policy rate goes up?

It was also interested in more granular questions: like the effect a company’s size or debt burden had. So, it took its list of ~800 companies, and very roughly, broke them down in two ways:

One, it separated small companies from large ones.

Two, it organised them by the amount of debt they had taken, relative to what they owned.

This would let it see what really mattered when the RBI’s rates were up.

One of the key things the RBI was interested in was the “cashflow coefficient” of these companies — or the degree to which a company’s investments depended on its cash flow.

To understand why, put yourself in the shoes of a company that’s planning to make a big investment. Where do you get the money for it? Do you dig into the cash sitting in your bank account? Or do you go to a bank and pick up a big loan instead?

In “normal” times, there’s a clear answer: companies usually avoid using their own cash for investments. If you can reliably get loans at reasonable rates, you’d rather invest your own cash somewhere you think you’ll get better returns. That is, you put a higher value on your own money than that of a bank. This is especially true of smaller businesses. Large, stable businesses may still look inward to fund an incremental expansion. But small businesses have a strong preference for loans.

When borrowing gets harder, though, things shift. Companies are suddenly a lot less comfortable with loans.

This creates an interesting dynamic. If a company is relying on its own cash, its capacity for investment depends on its cash flow. If it’s making huge profits and money is pouring in, they invest happily. When it doesn’t, they hold off. This does something fascinating: if you could just measure how closely-linked a company’s cash flows and investments are, that would practically be a pressure gauge. When that link is strong, outside financing is probably hard. When it’s weak, finance is easier to raise.

What the RBI found

For one, the RBI clearly saw that the “balance sheet transmission channel” worked in India, just like it did anywhere else.

When monetary policy was tight, companies found it harder to get external financing. If they still invested money in a project, chances are that they were using their own money, instead of borrowing any. The opposite would happen as monetary policy got easier. Companies would depend less on their own cash flows, because outside money was simply easier to find.

This is, really, the signature of the “balance sheet channel”. The amount of investment in an economy doesn’t mechanically flow out of interest rates. Companies invest in all sorts of different interest rate environments. Only, what they think about changes. Businesses make sophisticated decisions, carefully assessing their own conditions, and investing according to their capacity.

There’s more, however.

The RBI saw this dynamic play out a lot more sharply for smaller companies. These companies are often young, and are still creating the capital they need to flourish. Often, they have to invest to survive; what they currently own just isn’t enough to serve their customers. When things are good, they take loans and expand. In tighter financial conditions, though, it’s these very companies for whom borrowing becomes unaffordable. And so, their investment activity becomes very sensitive to their cash flow. Their investments, increasingly, are a question of how much money they have.

The script flips with larger companies. In tougher financial conditions, if anything, their investment activity is less sensitive to cash flows. Big companies have already made all the investments they need to survive. To these companies, when financial conditions get tougher, they try to consolidate. They hoard cash and delay investments. If they have to invest, meanwhile, their sheer size makes it easier to take a loan.

How leveraged a company already is, meanwhile, seems like a much smaller deal. The RBI saw both firms with high and low leverage behave rather similarly, based on where interest rates were. What matters, it seems, is not how indebted you already are, but how hard you find it to get your next loan.

What to take away from all this

If there’s one thing to take away from all this, it is this: repo rates don’t just tweak a single dial in the economy. Companies don’t invest merely because loans are cheaper, and they don’t cool down just because they’re more expensive.

Instead, they make complex calculations: around what they own, how much money is coming in, and how much they are comfortable borrowing. The repo rate re‑prices not just loans but entire balance‑sheets. It completely reshapes the risk calculus of businesses across the board.

This means different things for different companies. For smaller firms, a tighter policy can mean their entire growth strategy gets reduced to “how much cash do we have on hand?” For larger firms, it’s more about discipline — when credit feels expensive, they wait and watch.

Either way, the “balance sheet channel” adds a layer of complexity to how you see the economy.

The Economics of Air Pollution

At The Daily Brief, we often cover the economics behind the green transition, and the firms and governments building out renewable technologies.

But all these efforts are being undertaken because of one elephant in the room — air pollution.

The air we breathe shapes how (long) we live, which, in turn, affects our capacity to work and build things. It is as much of an environmental story as it is a macroeconomic one.

In other words, air pollution alters economic development as a whole. More than ever before, as we approach peak emissions, air pollution is quietly shaping the trajectories of many nations altogether. Including India.

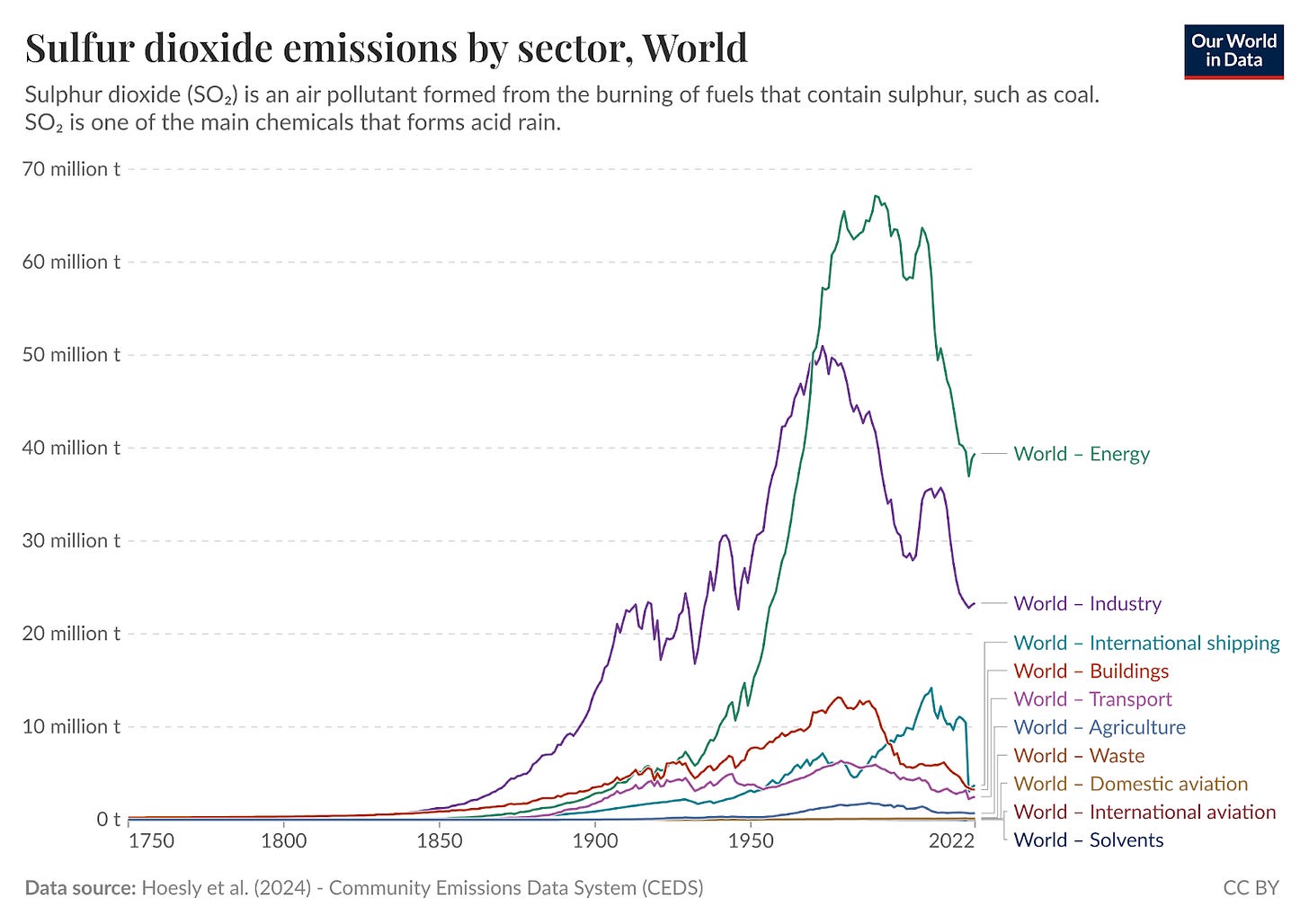

So, we decided to write a story about that. We’ve used the graphs produced by the excellent team at Our World in Data, and can’t thank them enough for such a wonderful public resource.

Let’s dive in.

Where does air pollution come from?

Where air pollution comes from can tell you a lot about how our economies work.

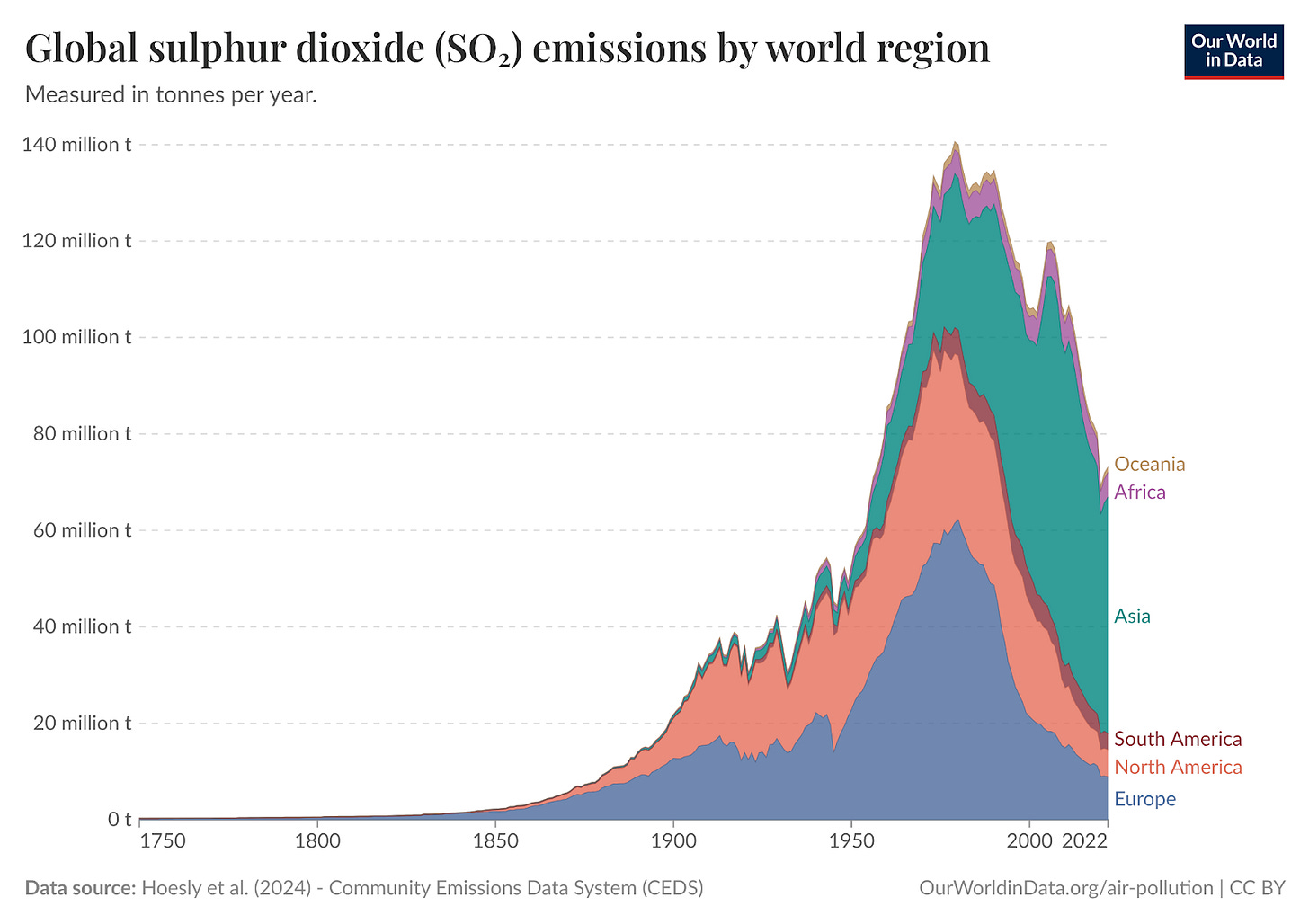

Energy production is the largest contributor, particularly coal-fired power. Industrialising countries often rely on coal because it’s cheap and available. But burning coal releases sulfur dioxide, which causes acid rain and respiratory illness. In 2022, energy production generated nearly 40 million tons of sulfur dioxide worldwide.

Next is transportation. Fossil fuel engines—cars, trucks, ships, planes—emit nitrogen oxides, which create thick urban smog. Road transport produces around 34 million tons of these emissions annually.

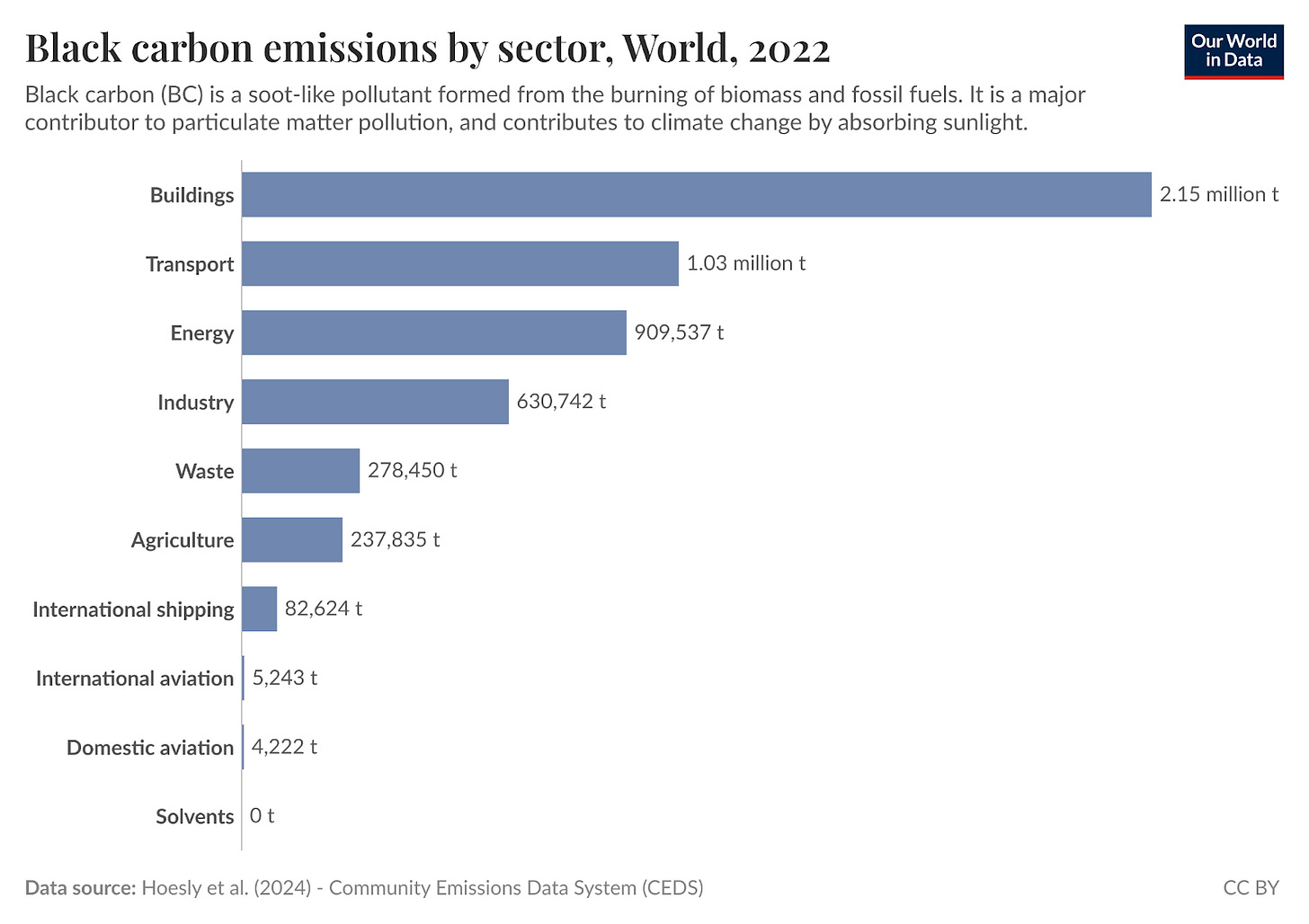

Then there's black carbon, or soot, from heating and cooking in buildings, and diesel engines in cars. In many developing regions, people still burn wood, charcoal, and biomass, adding to both indoor and outdoor pollution.

Agriculture adds a different layer. Livestock and rice farming generate about 139 million tons of methane annually. While methane is mainly a climate concern, it also contributes to ozone formation and thus affects human health.

These pollution sources come from the building blocks of growth: energy, transport, housing, and food. They release not just polluting gases, but also polluting solid and liquid particles that hang in the air (called particulate pollution). Countries can’t really eliminate these sources, but they need to transform them.

How Pollution Destroys Human Capital

It goes without saying that the human cost of air pollution is absolutely no trivial matter.

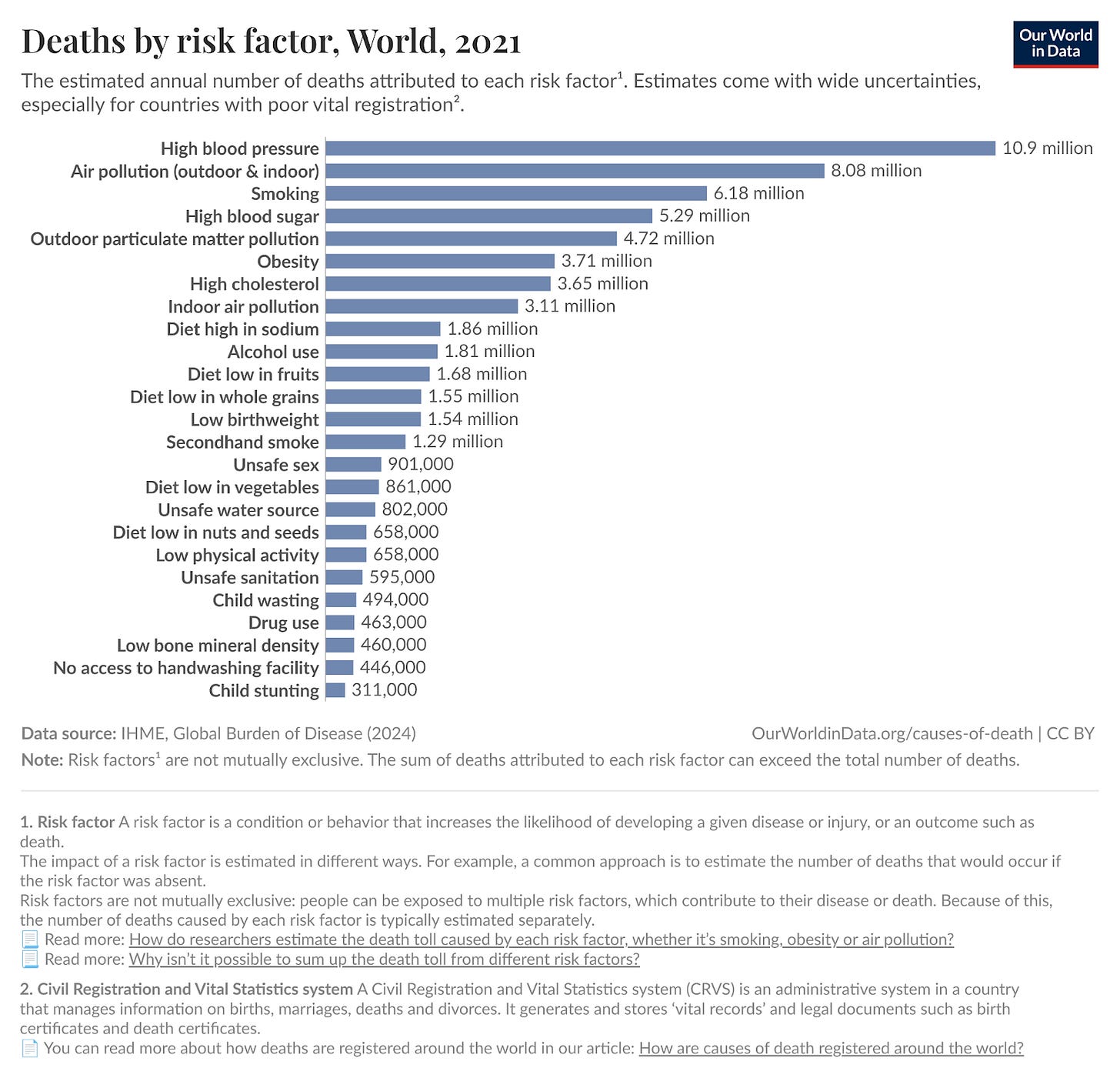

Roughly 8 million people die prematurely from air pollution each year. That includes about 3.1 million from indoor air pollution (mainly from burning wood, dung, and crop waste for cooking and heating) and 4.7 million from outdoor pollution. An additional half million deaths are due to ozone exposure. Air pollution now contributes to one in ten deaths globally, being only second to high blood pressure.

But on top of that, air pollution dampens economic productivity, too. This happens in three ways:

First, direct exposure to toxic gases causes immediate health problems. Workers with asthma, bronchitis, and other respiratory conditions are less productive, miss more work, and incur higher medical costs. Hospital admissions spike during periods of high pollution.

Second, many pollutants break down into particulate matter—microscopic particles that penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream. These cause heart disease, strokes, and cancer. This means the loss of workers in their most productive years.

Third, pollutants combine in the atmosphere to form ground-level ozone, which inflames lungs and damages cardiovascular systems. This leads to populations with long-term reductions in health and stamina.

The outcome: entire regions where human potential is eroded by the very air people breathe.

The Development Trap – And How Some Escape It

Poorer nations that rely on cheaper sources of energy aren’t just not progressing — they might be entering a development trap.

Around 2.4 billion people—one-third of the global population—still burn solid fuels like wood and dung for cooking and heating inside their homes. But the cheapest energy sources are the most harmful. Countries with a GDP per capita under $2,000 typically have less than 10% access to clean cooking fuel. Children suffer long-term health effects, adults face chronic illness, and families spend disproportionately on healthcare. Pollution creates cycles that keep poor people where they are.

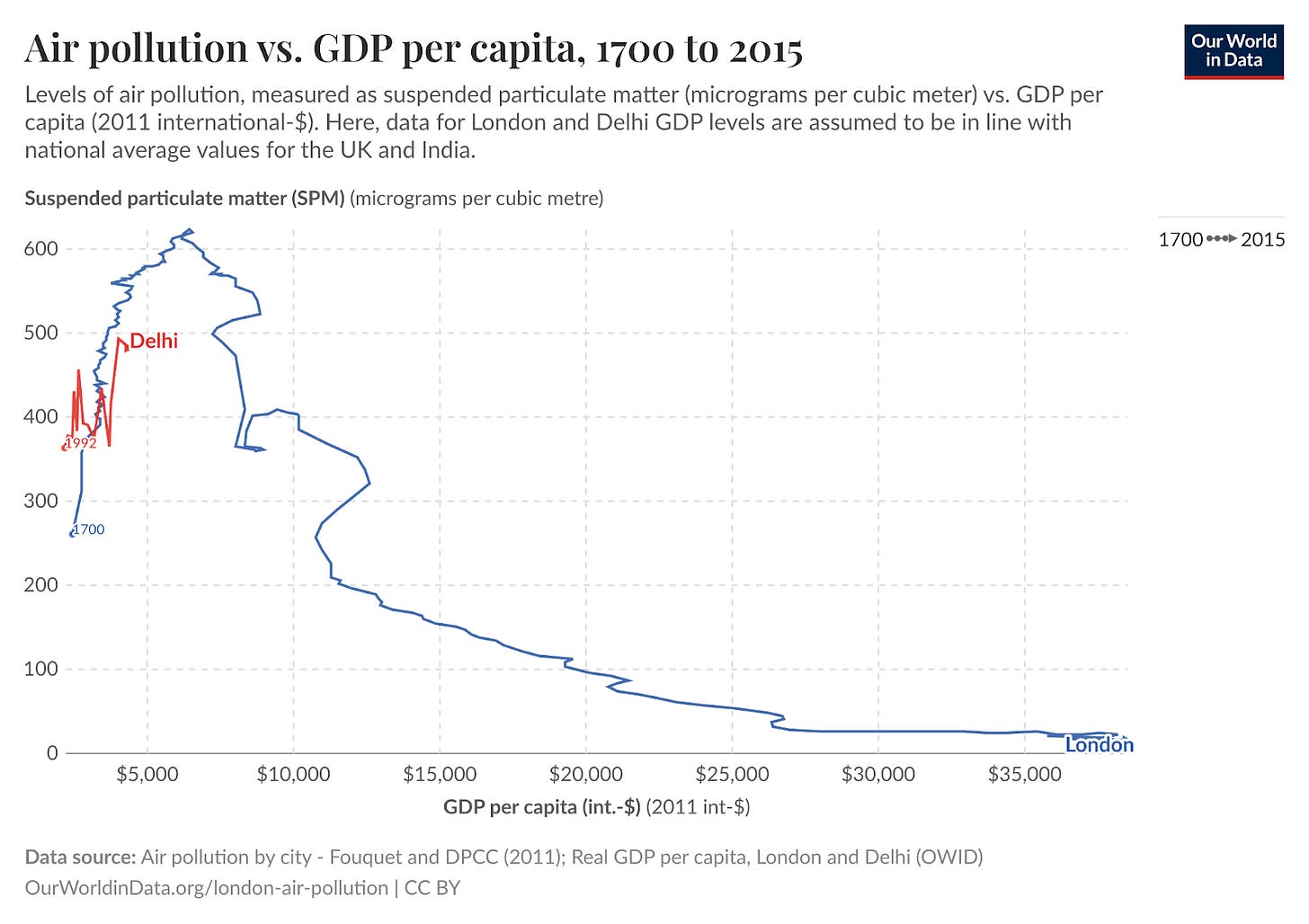

But that isn’t all. Air pollution worsens when a country pursues economic growth. As they attempt to build many industries, a lot of fuel gets consumed, leading to more harmful emissions. But emissions usually fall after peaking at middle-income levels. This trend is called an Environmental Kuznets Curve, and is quite common in the history of developed countries.

The UK is a classic example. During their industrial boom in the 1800s, London saw 80 dense fog days a year—some areas reported 180 in 1885. These weren’t natural fogs but toxic coal smoke. The city faced major health consequences. Deaths from bronchitis rose from 25 per 100,000 people in 1840 to 300 per 100,000 by 1890. At its peak, 1 in 350 Londoners died from bronchitis.

Eventually, London introduced cleaner fuels, implemented pollution controls, and phased out coal. Today, its air is about 40 times cleaner than during its worst period.

This shift wasn’t automatic, though. It took them nearly a century to turn the corner. And it required active investment in new technologies, infrastructure, and regulation.

The Acceleration Story

But here’s more good news: countries today can move faster than the UK did.

China offers a striking case. Sulfur dioxide emissions peaked in 2006 and have since fallen by 75%, even as coal use grew. This was achieved by installing pollution-control technologies that capture the sulfur pollutant before it gets mixed with the outside environment.

But that’s just an example of a country using technology to battle air pollution — policy can be extremely helpful, too. Take the case of the US after 1990. Beginning from 1990, they implemented cap-and-trade systems under the Clean Air Act Amendments. Basically, coal plants were given emission allowances, but exceeding them incurred steep penalties. This spurred the adoption of cleaner technologies and drove down emissions by 80% in two decades.

What took London a century, the US did in 30 years, and China in under 20 years.

There’s lots of progress within sectors, of which transport is a great example. In the UK, nitrogen oxide emissions peaked in 1990 and have now dropped below 1950 levels—despite a threefold increase in miles driven. This success came from stricter emission standards, catalytic converters, and improved engine design. Pollution per mile has dropped by 85% since the late 1990s.

Today, electric vehicles are eliminating tailpipe emissions entirely. Countries like Rwanda are mandating electric motorcycles in cities—primarily to improve air quality, not just for climate goals. And China is the largest driver of the electric vehicle revolution.

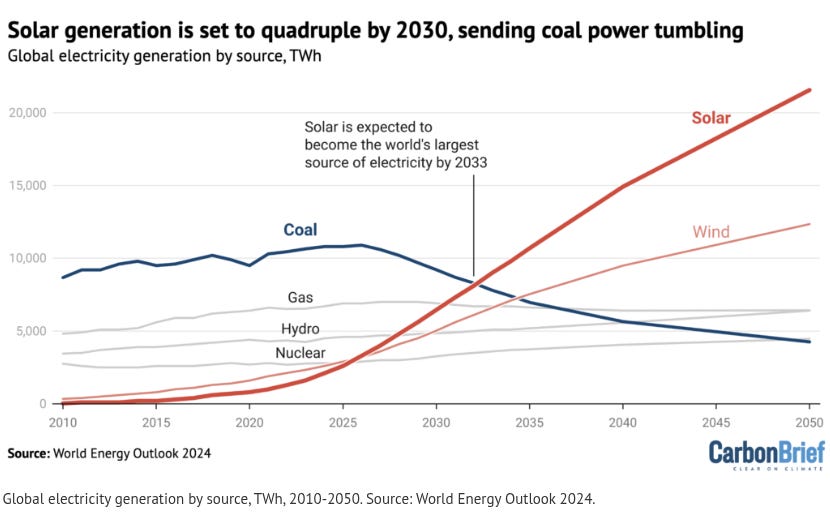

But most importantly, we have new sources of energy that throw up far less pollutants. The leading country in solar energy is also China — with a capacity larger than the next four nations combined. 26% of its energy production comes from wind and solar. However, much of Europe and India are also prioritizing renewables, too. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that solar will surpass coal as the world’s largest source of electricity within 10 years.

India: The Next Critical Test Case

India represents the key juncture in the Kuznets curve. Right now, it's where China was about 15 to 20 years ago: still on the upward slope of the pollution curve, but with access to modern technology and knowledge.

Today, all 1.4 billion Indians are exposed to unhealthy PM2.5 levels. Delhi’s pollution often reaches 450 to 500 micrograms per cubic meter—extremely high and dangerously mirroring London’s trajectory in the 1800s, though still below London's historical peak.

But here's what makes India's situation so economically critical: In 2019, air pollution caused 1.67 million deaths in India—about 17.8% of all deaths. The economic toll is shocking: $36.8 billion, or 1.36% of GDP.

To put that in perspective, that's economic damage equivalent to losing the entire output of a major industrial state annually. If air pollution is not aggressively controlled and managed, its costs could undermine India's plans to increase its economy to $5 trillion by next year. If India had met safe air quality standards in 2019, its GDP would have been $95 billion higher—thanks to fewer deaths, reduced absenteeism, and better productivity.

But unlike the old days, India has access to solutions.

The challenge remains in execution. Only 8% of India’s coal plants currently have technologies to prevent the spread of sulfur in the air. While over 50% of them have been awarded contracts to install them, delays and cost overruns are widespread.

This is crucial because unlike China, where sulfur dioxide emissions peaked in 2006 and have been falling since, India's emissions are still growing. Between 2013 and 2021, India accounted for over 59% of the world's increase in particulate air pollution. In November 2024, Delhi’s air quality index hit 494—the second highest since 2015. The response: the government mandated many companies to ask its employees to work-from-home, and many migrant workers began leaving the city.

There are some bright spots, however. Solar energy is one of them. As per various reports, we are among the top 5 solar power generators in the world. Between 2018-2023, our installed solar capacity tripled to 70,000 mega-watts. The government has announced a ₹24,000 Cr subsidy program to boost the domestic manufacturing of solar modules.

India’s ability to leapfrog the pollution curve will affect not only its own future but also global economic patterns.

Looking Forward

The Environmental Kuznets Curve isn’t a guarantee. Progress depends on deliberate action—investment in clean technology, strong regulation, and thoughtful development choices.

Some countries are accelerating through the pollution transition. Others remain stuck, facing high pollution levels without the systems to address them.

The countries that learn from others and act quickly will see healthier populations, stronger growth, and more stable development. Those that delay will pay the price in lost productivity, high healthcare costs, and population flight to cleaner areas.

The privilege we have today is that of having effective solutions to combat it. The question is now of implementation at the fastest speed possible.

Tidbits

Reliance Retail’s Q4 showed strong festive-driven momentum, but this latest move isn’t about short-term demand. It’s a long-term bet worth ₹75,000 crore to dominate India’s consumer durables market.

Reliance has acquired Kelvinator, the legacy home appliance brand, in a strategic push to expand its presence in the fast-growing premium appliances segment. With over 19,000 stores and a deep merchant network, Reliance now has the reach, and with Kelvinator, it’s adding brand equity.Source: Business Line

Earlier, we looked at Foxconn’s China troubles, from pulled engineers to blocked equipment. Now, the industry itself is sounding the alarm.

The India Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA), which represents giants like Apple, Tata Electronics, and Dixon, has written to the government flagging that India’s $32 billion smartphone export target is now under threat. The reason? Informal Chinese trade restrictions.

Key capital equipment is being held indefinitely at Chinese ports. Skilled Chinese workers, critical for final assembly setups, are being blocked from travelling. Several Chinese suppliers have even cancelled India expansion plans altogether.

Source: Business StandardAdding to the steel saga that we are seeing and writing about over the past few months:

India's iron ore imports are projected to rise to 8–10 million metric tons in 2025, up from 6 million tons last year, driven by increased demand from JSW Steel. Falling global prices, currently below $90 per ton, are making overseas purchases more attractive for the country's largest steelmaker.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Bhuvan.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Article on repo rate seems a bit repetitive in narrative, the last para is what is needed. Big fan of daily brief but this one didn't satisfy.. 🤐

you have mentioned agriculture and dairy farming among the causes of air pollution. haven't mentioned anything about animal slaughtering. Which one is more polluting agriculture and dairy farming on one side and slaughter houses on other side ?