Japan and the future of an ageing world

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

A land without children: What Japan’s example can teach us

How India's night-shift reforms are reshaping women's work

A land without children: What Japan’s example can teach us

Two days ago, at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda delivered a demographic wake-up call. The symposium brings together people from across the world of finance — from central bankers, to financial industry leaders, to academics, to government officials — to talk about long term financial policy decisions that concern everybody. What Ueda pointed to was just that.

He was talking about one of the most profound transformations in modern economic history: across the world, populations are growing smaller and older. According to conventional wisdom, those are terrible conditions in which to run an economy.

Japan’s case, specifically, is hardly surprising. It has been in this bind for over half a century.

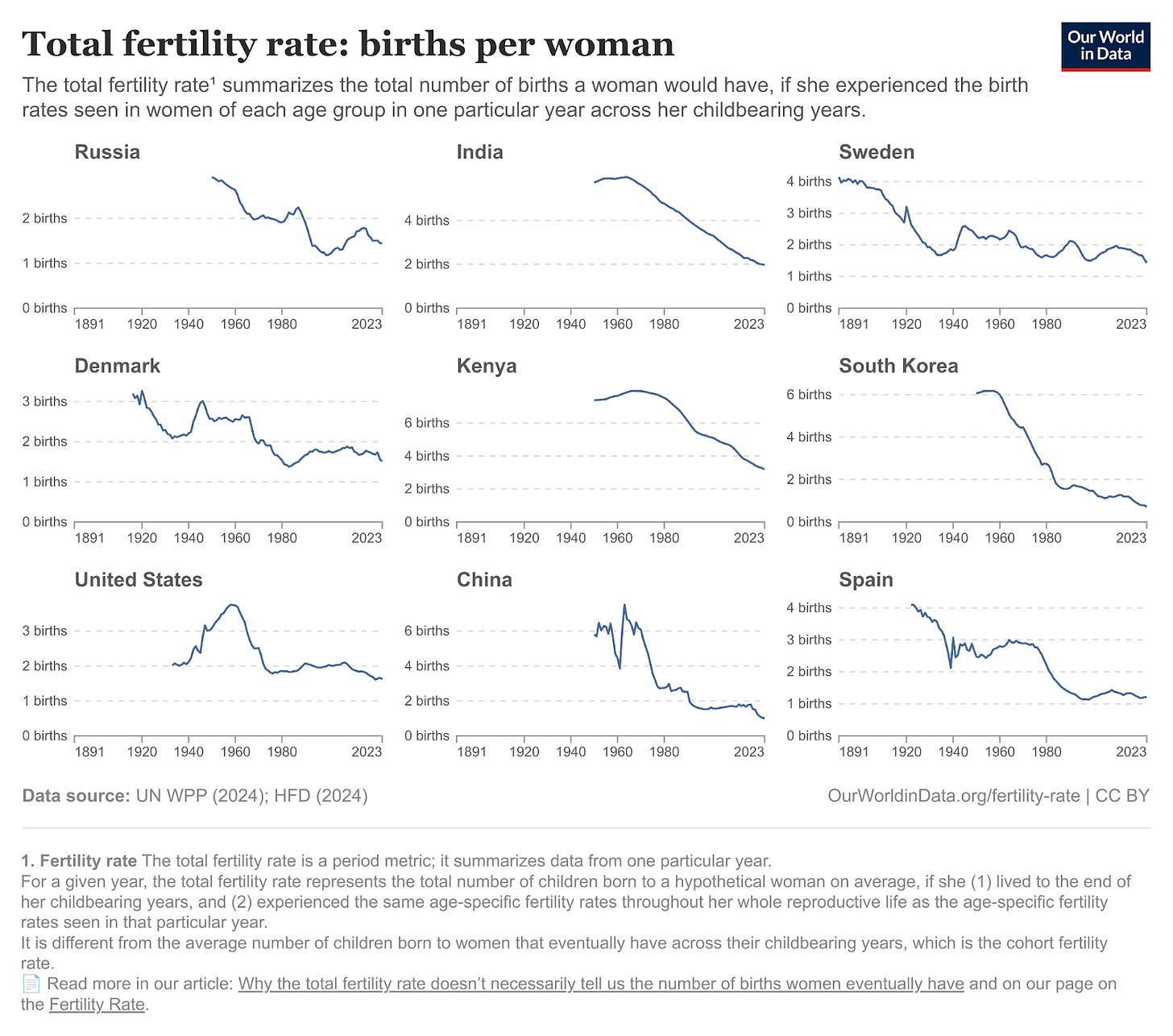

Japan was a “canary in a coalmine”. But slowly, its story is becoming everyone's story. According to the IMF, over half of the world's economies — representing two-thirds of the world’s population — now have “fertility rates” below what’s called “the replacement level”, i.e. 2.1 children per woman. Roughly speaking, at this point, the number of children being born into a country balances out the number of people dying within it. Any lower, and the country’s population quickly becomes smaller and older. We’re now seeing this play out in most of the world.

And so, Japan’s experience has become relevant to everyone else. If you want to try and understand what happens in such a scenario, Japan presents a ‘template’ for what to look for.

That’s what we’re trying to decode from Ueda’s speech.

Japan’s population crisis finally breaks through

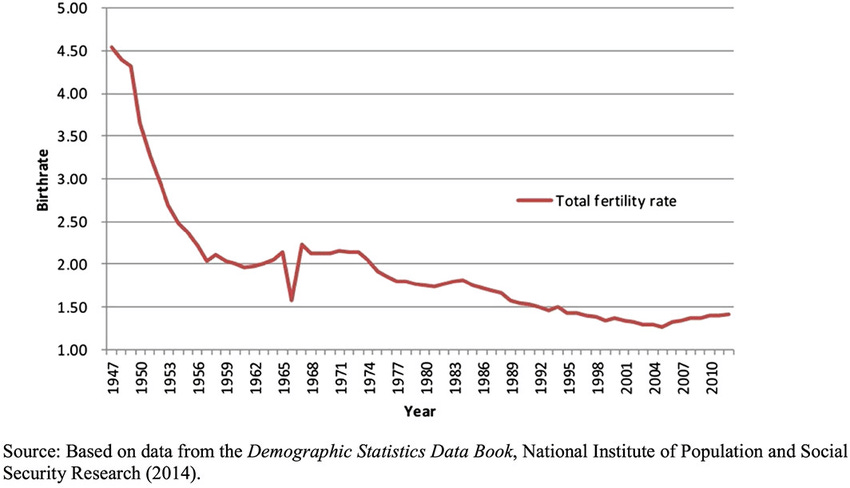

In the early 1950s, the average Japanese woman would have around four children. Men usually lived to be about 64, while women lived till 68. But something changed over that decade. By 1960, the country’s fertility rate had halved. And then, it fell even further.

By 2024, its fertility rate had collapsed to just 1.15 children per woman — among the world's lowest. Meanwhile, life expectancy soared. Japanese men now live to 81, on average, while women live to 87.

This was a demographic double-whammy. An ever-larger number of Japanese people were living to ripe old ages, but very few children were being born. The country was losing its youth. Its working-age population reached its zenith in 1995, almost 30 years ago, after which it began falling. By 2008, its total population had begun declining as well.

It has now seen over a decade of population decline. That decline, however, took its time showing up in the data.

The hidden crisis

For decades, if you were just looking at Japan’s job market, the crisis would have seemed invisible. Through the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, unemployment remained high while wages stagnated. There were few tell-tale signs of a shortage of workers.

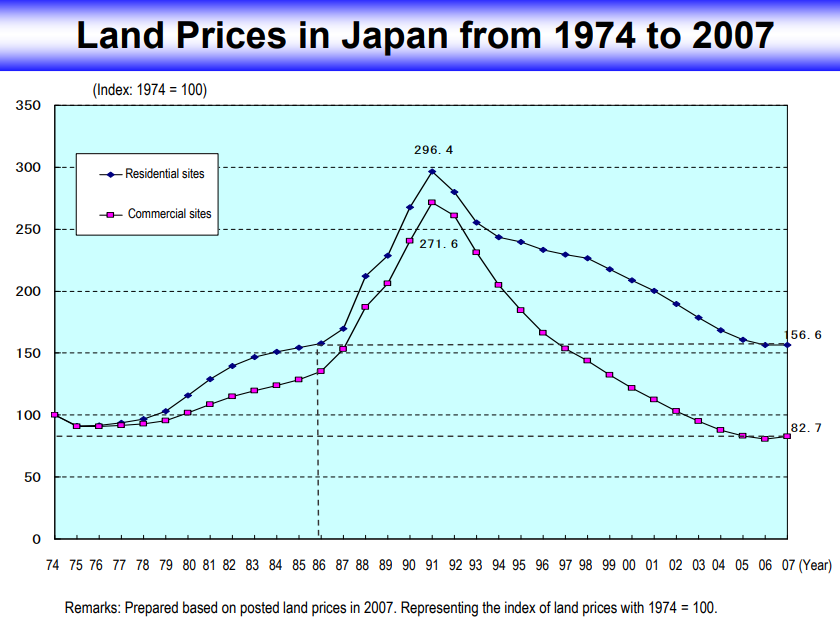

That was because of a very peculiar happenstance. Japan was trapped in what Governor Ueda calls a "deflationary equilibrium." The country had seen a profound asset bubble burst in the early 1990s, which killed the vitality of its economy. The country entered three decades of economic stagnation. It was stuck: people weren’t spending; businesses found themselves unable to raise prices; so instead, they refused to raise wages, even if they had room to; and that limited people’s appetite to spend even further.

Those years were hard on the workers that were part of its economy. From the mid-1990s until 2022 — nearly three decades — full-time workers barely saw their wages budge. Base wage growth was stuck in a band between (-)1% and 1%.

But those waiting outside were caught in a waking nightmare. Millions of men and women simply found no way to enter a stalled economy, creating a “lost generation”. Instead of a worker shortage, Japan’s economy was too weak to even accommodate its depleting workforce.

With few jobs to go around, Japan’s demographic pressures stayed under the surface. Breaking out of this, as Ueda said, required "a large external shock."

The COVID breakthrough

That shock came from an unexpected source: post-pandemic global inflation.

As supply chains broke under the pressure of world-wide lockdowns, central banks across the world flooded economies with money. As money poured in, Japan saw something it hadn't seen in decades — meaningful price increases.

By early 2023, Japan's inflation hit 4.2%. To most countries, this would barely register as abnormal, but for a country with three decades of flat prices, it was seismic. It finally broke the economy-wide belief that prices would stay still.

The results were dramatic.

In spring 2025, wage negotiations across the economy delivered a 5.25% wage increase — a 34-year high. This wasn't just happening at big corporations. Wage growth spread all the way down to small and medium businesses — the backbone of Japan's economy. Its data now shows employment conditions at a level of tightness not seen since the late 1980s, back when its economy was in a massive bubble.

Japan’s generation-long “employment ice age” may finally be coming to an end. And its demographic change is finally becoming evident.

The changing character of Japan’s workforce

Japan’s workforce didn’t remain unchanged through its years of economic stagnation. Those demographic changes were making themselves felt under the surface. They changed the character of Japan’s workforce. And recently, those changes have accelerated.

The participation revolution

Through those stagnant decades, Japan had been paving the way for new cohorts to enter its labour pool. Groups that were previously underrepresented in the workforce were finding it more feasible to work.

Women led this transformation. In the early 2000s, only ~60% of women aged 15-64 participated in the labor force. That number has risen considerably since — a result of policy changes, combined with social evolution, as per Governor Ueda. Japan greatly expanded social insurance for its part-time workers over the decades, and massively increased its childcare capacity. Meanwhile, Japanese society was growing more comfortable with working women. By June 2025, 78% of working age women were part of its workforce — numbers otherwise seen only in Northern Europe.

Seniors followed a similar pattern. Japan changed its laws to nudge older people to work: requiring firms to ensure employment until age 65, and make an effort to provide opportunities until age 70. Today, over a quarter of Japanese people aged 65 and older work — the second highest rate among OECD countries.

As more women and seniors took to work, they compensated for the overall decline in Japan’s working-age population. Even though Japan was facing a severe demographic declined, more Japanese people are employed than ever.

But this trend comes with an expiry date. The scope for further increases is limited. Japan’s female labour matches the highest rates in the world, as does its senior participation. Anyone that can work, in short, does work.

There are only two levers that Japan has left to expand its supply of workers. One, nearly half of Japan’s working women are part-time workers, and with the right policies, many more could become full-time employees. Two, Japan can draw in more foreign labour. While foreign workers account for only 3% of Japan's workforce, in fact, they contributed over half of its labor force growth between 2023 to 2024. But there are limits to how much either can add to Japan’s labour pool.

Ultimately, though, an economy isn’t just defined by how many workers it has.

The mobility transformation

Japan's labour market is also seeing a cultural revolution.

Until recently, the Japanese economy was organised around the “salaryman”. You would dedicate your life to a single job: you would join right after university, and stay there until you retired. Job-switching was rare. That's changing rapidly, however. Governor Ueda's data shows regular employees switching jobs has been increasing, especially among younger generations.

This has had an interesting effect.

When companies locked workers down for life, they faced little pressure to raise wages to keep their staff. But as people become more willing to change jobs, companies suddenly find themselves competing for workers.

This has driven wages up, of course. But it has also had more unexpected effects.

Many small and medium enterprises lack the ability to match these rising wages. They’re instead closing down, or merging into bigger firms. Their workers are being released into the broader market.

Under normal circumstances, this would be traumatic. But in the special case of Japan, according to Ueda, this might be a good thing. See, an economy doesn’t simply grow by increasing the number of people in it. It can also grow by making its existing workers more productive. That’s what we’re starting to see. As small workers close down, given Japan's acute labor shortages, those workers are quickly getting absorbed by larger, more efficient firms that can pay higher wages.

With the same labour pool, and fewer businesses, Japan is interestingly gearing up to do more.

The technology response

Japanese companies are also turning to technology to make up for their worker shortfall. Firms in sectors that traditionally employed large workforces — like hospitality or retail — are investing heavily in labour-saving technologies. Software investment growth in these industries, in fact, outpaces other sectors. Jobs one reserved for labour are being taken over by capital.

That puts Japan in a weird spot in the AI debate. Where so much of the world is worried about AI displacing young workers, Japan has a more nuanced view. As governor Ueda said, "Whether AI will provide just enough substitution to offset demographic decline remains to be seen."

The words “just enough”, there, is telling. Japan’s hoping for AI adoption to fall into a Goldilocks zone. Too little, and AI won't be able to replace the productivity of its shrinking workforce; too much too fast, and it might see another phase of joblessness.

What can the world learn from Japan

The changes that Japan sees today could be those that the rest of the world shall see tomorrow.

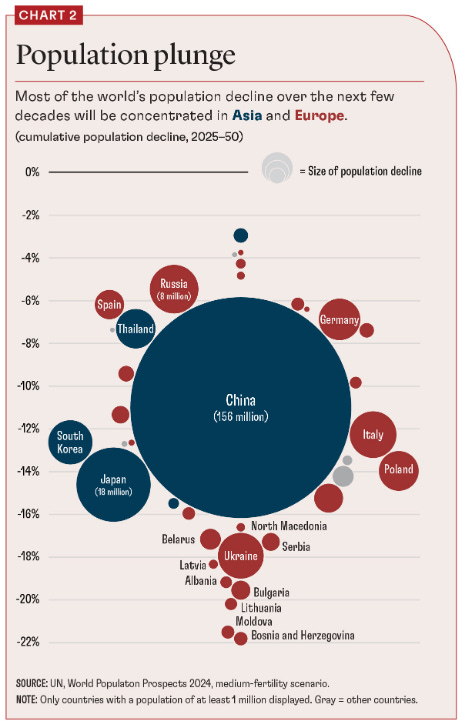

Over the next 25 years, 38 different countries with populations above 1 million will see their populations fall — up from 21 in the last 25 years. Some of these shifts will be seismic. China alone, for instance, is projected to lose 155.8 million people. In fact, most parts of the world will see their populations stagnate, or fall. The only major exception is Africa, where fertility rates are still high.

What would that world look like?

To many people, this can only bring doom. As countries move towards smaller, older populations, the rate of technological change could slow down. There will be fewer innovators and fewer new ideas. Over the long term, the world may even stagnate. Many countries have social safety nets that are premised on non-stop growth. Shrinking, aging populations could strain that net. Indeed, that sounds like a terrible future.

But Japan's experience offers a different perspective. Demographic decline doesn't automatically mean economic decline.

If conditions align, you might see a world emerge that looks very different: one where workers gain more power, social barriers fall, and technological adoption accelerates. Even though Japan’s recent economic history has been full of pain, ultimately, its demographic shifts may even be positive.

The fertility paradox

There’s a paradox at the heart of this story, however: while Japan’s economy has done a remarkable job of adapting to its demographic decline, those very adaptations may make its demographic challenge harder to solve.

As labour markets tighten, and women gain better career opportunities, having a child seems like a bigger sacrifice than ever. Somewhere, Japanese people are rethinking the idea of having a “family”. A fertility rate of 1.15 children per woman isn’t a mere number — it’s a cultural phenomenon. It points to a society where having children is unattractive, whether for cultural, economic or social reasons.

This isn’t limited to Japan. There are parts of the world — like France or the Nordic nations — that have made massive public investments into increasing their fertility rates, through generous parental leave, subsidized childcare, or child allowances. The scale of these investments has been enormous. But even these countries see below-replacement fertility.

This might just be a reality we have to live with.

The new normal

Japan was a canary in a coal mine. It was the first country whose population went into free-fall. And through this phase, it was hit by a multi-decadal economic nightmare.

But if anything, Governor Ueda’s speech signalled hope. Japan’s example has shown that economies can adapt to shrinking populations. It presents a template for how advanced societies could navigate one of history's most profound demographic shocks. The implications of this extend far beyond Japan. Over coming decades, countries across the world will face similar transitions.

Will those other societies implement the structural changes Japan is pioneering? And perhaps more importantly, can they do this while maintaining social cohesion and economic dynamism?

Japan's story suggests the answer might be “yes”. In the coming years, we will learn if its example is an aberration, or if it is the norm.

How India's night-shift reforms are reshaping women's work

From Japan, let’s turn to India, where the picture looks very different. As we’ve covered previously, the share of working women in India, particularly in manufacturing, has been stagnating.

To us, this isn’t just crucial for the sake of diversity. Higher female labor force participation is a key driver of economic development in most emerging economies. But in India, women face a series of barriers that keep them out of the workplace — from family attitudes to workplace discrimination.

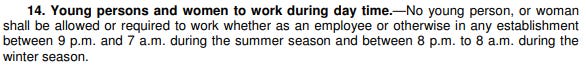

There’s also a legal side to this, however. Many Indian laws actively prohibit women from some types of work — for instance, from working night shifts. Delhi, for instance, bans women from working after 9 PM during summers, and 8 PM during winters.

The intention behind these laws, perhaps, was to ensure women’s safety. But increasingly, this is seen as a systemic barrier to their employment.

Between 2016-2023, 8 Indian states — including major economic hubs like Gujarat and Karnataka — decided to change this. They amended their laws to remove this ban. Economists Nisha Vernekar and Karan Singhal looked at the varied impacts of the repeal of this ban, specifically on women in the services sector, in a new paper. Their paper reveals how laws interact with India’s economic structure in complex ways.

Let’s dive in.

More than just a legal tweak

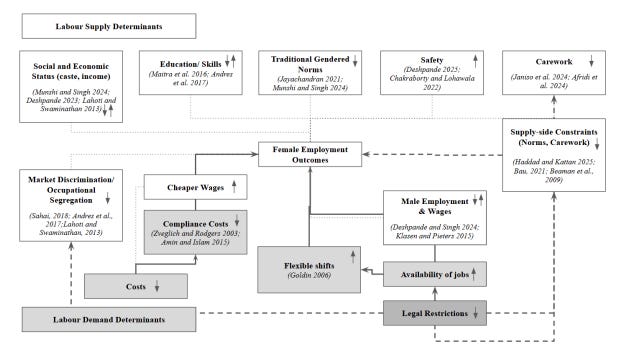

Many researchers look at our poor rates of female employment in India through supply-side factors. That is, they look for reasons that stop women from supplying their labor to firms: things like family responsibilities, or safety fears.

A ban on women working the night-shift, in contrast, is a demand-side barrier. It makes women less attractive candidates for businesses. To an employer choosing between a man and a woman, the law made the latter an inferior choice — you simply have less legal flexibility on where you can deploy female workers, regardless of their qualifications or willingness to work.

These laws systemically excluded women from many formal, well-paying jobs — especially those in the services sector.

Consider India's GCCs, for instance. They offer many well-paying positions in call centers, software development, and technical support. But many of their clients live in other timezones, and they need to run night shifts to serve those global clients. Or think of hospitals — they cannot function without a skilled nursing staff that works 24x7.

If you ran such a workplace, would you employ a woman?

Now, these laws contain a labyrinth of exceptions and grey areas, creating breathing room to some workplaces. That said, they pose a hurdle to hiring women that simply doesn’t exist for men. So, when these laws were done away with, it represented a test: how important was this demand-side barrier really, for female employment in India?

The answer, it turns out, is complex.

The test results

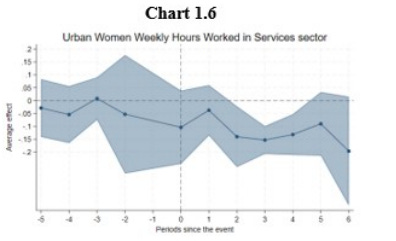

A major finding of the paper was that, to a large degree, many women reallocated their work time from day shifts to night shifts. Relative to men, women in the services sectors were also taking up night shifts faster and more enthusiastically.

This does not mean that their working hours increased overall — in fact, the paper found that the women they studied actually worked 12.2% fewer weekly hours on average.

For women who have caregiving responsibilities during the day, it seems, night-shifts are attractive: they offer better work-life balance. Night work may also bring higher wages, allowing women to earn similar income while working fewer total hours.

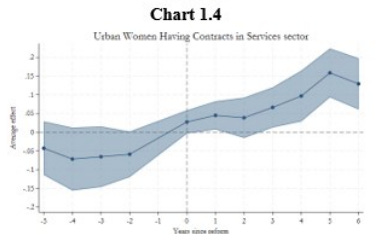

Along with this time reallocation was another important, related finding: more women got formal jobs. If you’ve read our story on India’s broken job market, you would know that India is filled with informal jobs that have no social security and insurance, no contracts, and no recourse to the law if something goes wrong. And women suffer the brunt of informality far more than men.

But women in the states where laws were reformed, it turns out, were 8% more likely to have a formal employment contract. In other words, allowing night-shifts translated to more decent, flexible working conditions for women — while helping them reallocate their time better.

There’s a sound logic to this. Earlier, firms would employ women for night shifts illegally, without formal contracts. Women worked night shifts anyway, but on top of that, they had no labour protections either.

Once night work became legal, employers had to offer new protections — like providing safe transportation and better security. Simultaneously, women gained bargaining power: they could now leverage their new legal right to work at night to demand better employment terms.

Another paper by economists from Ashoka University (Bhanu Gupta, Kanika Mahajan and others) found similar results about manufacturing too.

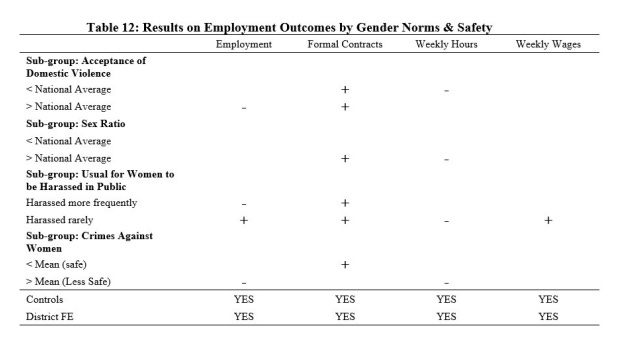

However, these results are not uniform. There are places where they moved the needle less than expected. For example, the reform did not improve actual female employment rates, nor did it do much to boost weekly wages for women as a whole. The results, it seems, were spread unevenly. Different women were affected differently — based on where they lived, where they worked, and how much they already earned.

The winners win, the losers lose

Our biggest learning from the paper was this: the law doesn’t work in a one-size-fits-all manner. Instead, it plays off against other social factors in weird, often fascinating ways.

For one, geography really matters.

The benefits of these reforms went almost entirely to large cities. Smaller towns practically saw no difference. One reason, perhaps, is that infrastructure determines how effective such a reform can be.

Here’s one example: under the law, if a company wants to hire a woman for the night shift, it has to provide her with transport facilities. Practically, that means the company has to contract with a cab service, or arrange for a shared shuttle bus. In big cities, such services are easier to find. But in smaller towns, where the infrastructure is poorer, it becomes too expensive for firms to procure such services.

Secondly, women in already-existing large, formal companies gained the most.

Big firms, by virtue of their size and finances, could absorb the compliance costs of hiring night-shift women workers much easier. Given the scale at which they employed women, they had more efficient ways of complying with the law. The benefits of employing women at night, to them, were higher than their costs of compliance.

On the flip side, women working in small, informal firms couldn’t move up the ladder. Those firms found the new compliance costs too expensive, leading them to either avoid hiring women for night shifts, or reduce their hours to manage costs. If a firm was already employing women at night by skirting the law, these costs stopped them from doing so legally — so they didn’t make the switch.

This created a divided outcome — the reform vastly improved the more urban, already-formalizing segment of the economy, but those women that previously worked small, informal jobs saw no real change to their lives.

The change was also most likely to help younger women whose families already earned well, and did not come from disadvantaged social groups. These were, perhaps, the very women that had the privilege and connections to land jobs with large companies in big cities. These reforms helped them negotiate favorable terms to work at night when that possibility opened up. If you didn’t have that privilege, however, the reform has less of an impact on your life.

Safety as economic infrastructure

Vernekar and Singhal put a crucial caveat to their results: these reforms only bring change if women feel safe. Safety, they highlight, is a very big determinant of how well such a reform works.

In areas with low levels of crimes against women, the reform worked ideally: increased employment, higher wages, reduced working hours. But in unsafe environments, the reform didn’t just not help women, it harmed them. In places where sexual harassment was already a problem, the reform backfired completely. It actually brought a decline in female employment.

Possibly, in unsafe areas, such a policy would have increased anxieties among women. Now that an employer could legally ask them to work at night, they would rather withdraw from the workforce rather than risk such a possibility.

Safety, it seems, isn’t simply a social good — it functions as essential economic infrastructure. Without it, economic liberalisation can cause more harm than good. When the law becomes more permissive, it heightens fears instead of expanding opportunities.

Social norms, the authors found, were another fundamental factor in whether these reforms did anything. In states where people tend to turn a blind eye to domestic violence against women, the reform hardly changed anything. These were perhaps more patriarchal states, where women didn’t have "social permission" from families to take up a formal job — let alone at night. Permission by law, then, means very little.

The way forward

So, how should you see these legal reforms?

Well, it’s complex. Legal reforms are necessary to boost female employment. But they aren’t sufficient. Without complementary reforms elsewhere, they do little — in some cases, they’re even harmful.

Any state that’s trying to reform their laws to bring more women to the workplace, therefore, need to add a couple of additional things to their policy playbook:

Safety as a part of economic policy is first and foremost among them. The safer women are, the better they’re able to participate in the economy. Even small things — better street lighting, reliable public transport, and effective policing — can go a long way towards making that happen.

Secondly, economic policy and urban planning go hand-in-hand. Cities are where people go to get a good job. The better our cities are, the more likely people are to find working conditions that they can accept. If our cities are poorly designed, and have poor infrastructure, even excellent laws can only do so much.

Finally, while compliance requirements are often necessary, they’re also hard to follow — especially for smaller firms, for whom those costs can seem too high. If states do nothing to make it easy for them to comply, they can often be locked out of doing things the law allows on paper. Along with compliance burdens, therefore, governments could provide tax credits, subsidies, or technical assistance to small firms, letting them stand on a more equal footing to large companies. Some states, like Tamil Nadu, are already doing this by subsidizing women’s salaries.

For India's policymakers, the lesson is clear: legal equality is merely a starting point, not the ultimate goal. Without a holistic approach, even good laws can make inequalities worse.

Tidbits

The Reserve Bank of India has approved Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) to acquire up to 24.99% stake in Yes Bank, according to the bank’s stock exchange filing. Crucially, RBI clarified that SMBC will not be treated as a promoter, sparing it from additional regulatory obligations.

Source: Reuters

Blue Star now expects its room AC sales to grow up to 20% this year, higher than its earlier 10–15% forecast. The boost comes from the government’s plan to slash GST on consumer goods and appliances from the current 28% slab, potentially down to 18%, starting October. But in the short term, the industry may see a slowdown as buyers delay purchases until the tax cuts kick in — even during the festive season.

Source: Business Line

Dream11 has opened talks with the Board of Control for Cricket in India to exit its ₹3.58 billion jersey sponsorship deal due to the newly enacted ban on real-money online games. Under the new law, advertising, promotion, or sponsorship of such platforms is now prohibited, making the continued branding on the national team’s jerseys legally untenable.

Source: Reuters

India’s market regulator, SEBI, has approved LIC’s request to be reclassified from promoter to a public shareholder in IDBI Bank—stripping it of board rights and limiting its voting power to 10%, with a mandate to cut its stake to 15% or less within two years. This marks a key step toward the planned privatization of IDBI Bank, with financial bids expected between October and December as the government and LIC prepare to divest a combined 60.7% stake.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

I compliment TDZ for articles that have Hidden Brains that will affect Economies other than GDP growth in long term.TDZ has excelled in digging deep and shares us valuable insight that Japan’s example has shown that economies can adapt to shrinking populations.As TDZ mentions we are living in A Shrinking World.By the end of this century, the global population will almost certainly start to shrink. Global birth rates will have to increase and stay there. Absent that, simple math dictates that the population eventually falls to zero.So,Japan or other countries need to adapt policies for shrinking population beyond economic growth.

In her novel, Scattered All Over the Earth, Yoko Tawada imagines a world in which Japan has physically vanished and Japanese-ness survives only with a handful of natives and Japanophiles.

In Japan octogenarians may soon be filling jobs like taxi driving if a rule change takes place. There’s very little slack in the labor market, “Nearly 87% of the working-age populace is employed, well above the 79% average of countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development,” says Gearoid.

The other article—How India's night-shift reforms are reshaping women's work—is very informative and if I’m not making a mistake,part of the article was covered in a previous TDZ.

The ultimate single unit of economic backbone is the human mind. Without people, there’s no supply, no innovation and ofc no consumption.

India thinks overpopulation as a burden. Maybe it’s not the best way to look at it - given Japan’s example.