Is Europe a lost cause?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Europe’s Vanishing Power

Sanctions, Oil, and India’s Game Plan

Europe’s vanishing power

How many super-powers does the world have? There’s definitely one: the United States. There’s also an obvious superpower-in-waiting: China. Chinese people may not have the same standard of living as their Western peers, but when it comes to national power, the country punches well above its weight.

And then, there’s another superpower, though it hasn’t lived up to the name in a long time: Europe.

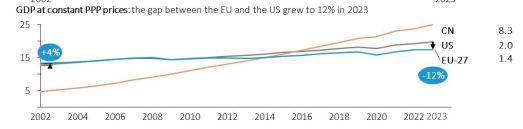

On paper, Europe should have everything going for it. With a population of 440 million, it represents 17% of global GDP. It boasts a variety of heavily industrialized economies, and governments that can provide stellar outcomes in health, education, and climate policy. In the early 2000s, it was bigger than both, the United States and China, at least on a purchasing-power-parity basis.

Yet, today, it lags both as a distant third. It has a muted international presence, and declining clout. So, today we ask: why has a continent-sized economic bloc with so much potential fallen so far behind?

The answer is rooted in complacency, structural contradictions and external shocks.

A neoliberal experiment

Europe’s integration was a product of the neoliberal era.

While ‘neoliberalism’ has come to become a catch-all term for whatever people hate about capitalism, at its core, it believes in four freedoms: the free movement of people, goods, capital and information. This comes from a fundamentally cosmopolitan outlook, where “societies” and “nations” mean little, and all the world’s people are the same — they’re just competing to buy and sell things from each other. Everything else is a distraction. In this view, the world’s governments would slowly stop trying to fight each other, or push for any national priorities. They’d recede from people’s lives and eventually become mere providers of key infrastructure.

This way of seeing the world was much more popular thirty years ago than it is today. And because the EU was just being formed, the four neoliberal freedoms were baked into its very structure.

In this new regime. Europe was conceptualised as a ‘common market’. While countries still had autonomy over ‘provincial’ matters like education or defence, they ceded a great deal of control over economic aspects of policymaking. Everything from trade, to competition, to monetary policy was now to be run by a continent-wide bureaucracy, based on neutral principles.

This structure had its limitations. The Eurozone debt crisis was a product of these limitations. European countries no longer controlled their own currencies, and had strict limits on what their governments could spend. And so, when a crisis came about, they didn’t have the tools to respond. Many countries on the continent’s periphery — like Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain — were hurt terribly by this lack of control.

But while reforms followed, its overall structure persisted, because it simply worked too well — at least at the time.

Europe’s golden advantages

In its heyday, Europe had three big things going for it:

Openness to foreign trade: Foreign trade accounted for nearly half of Europe’s GDP — much more than it did for the US — making it the global hub of commerce.

US security umbrella: The United States was an all-weather ally of Europe, and underwrote a great deal of the continent’s defense costs. Europe, meanwhile, could redirect resources on economic and social development.

Cheap Russian energy: Since the 1990s, Russia’s fossil fuel industry has supplied affordable energy, which fueled Europe’s industries and households.

These were big advantages, and they maintained Europe’s status as a global power centre for decades. Unfortunately, these advantages also bred complacency.

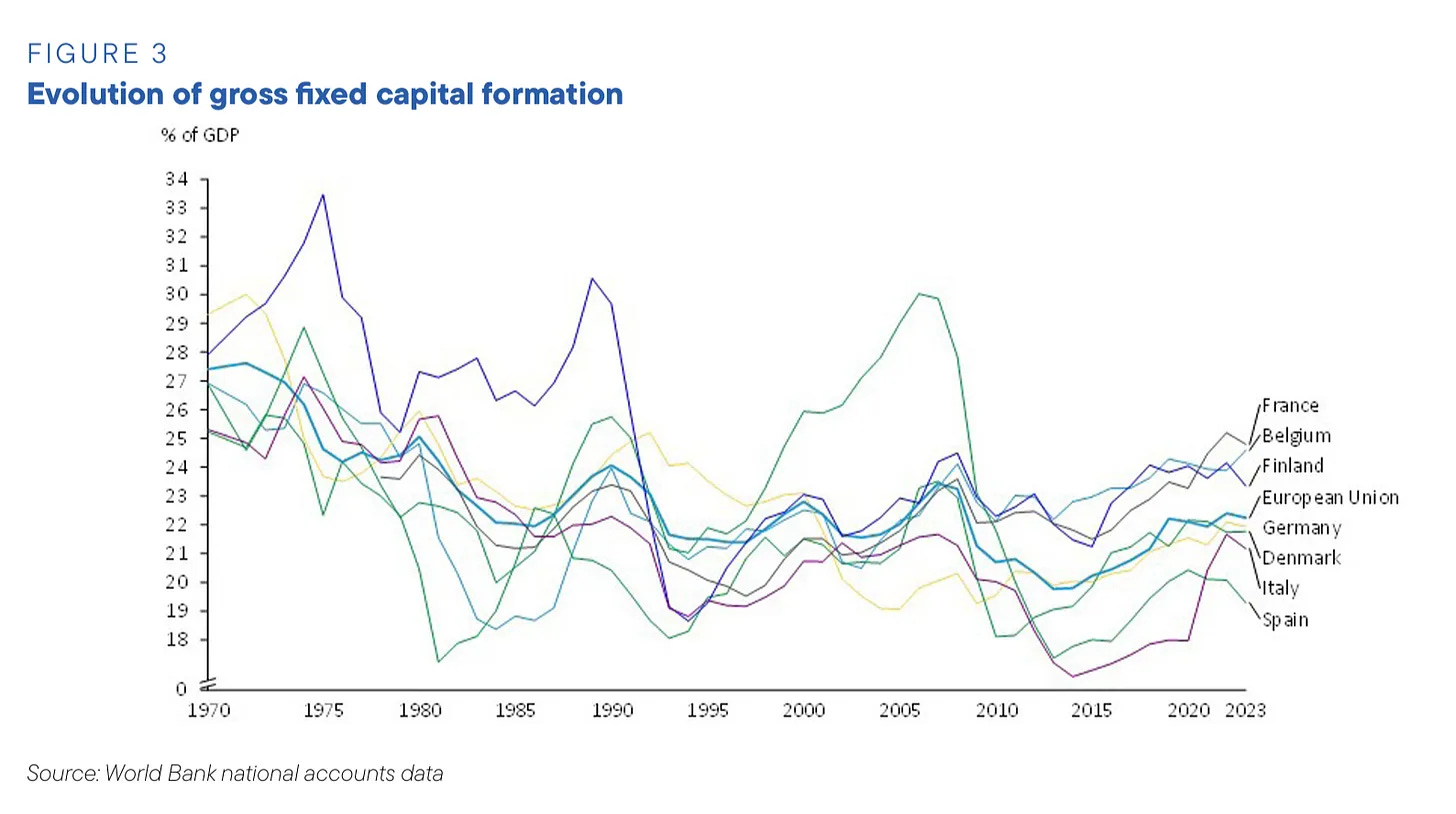

The continent slowly lost its competitive edge. Investment in infrastructure and education stagnated.

Productivity waned.

The continent papered over this decline with the belief that, with the right regulatory policies, it could maintain its strength. After all, Europe was arguably still the world’s best market. Every company in the world wanted to sell its wares in Europe. This created a point of leverage that Europe could use to maintain control over everyone else.

Many good things came out of this — from global scrutiny over big tech’s data policies, to the universal Type-C charger. At the same time, however, this led to major regulatory overreach, making life hard for European businesses.

The poly-crisis

Europe’s reliance on its past successes left it ill-prepared for the tectonic shifts of the coming years.

In the last decade, the continent has been hit by a series of crises — each of which feed into each other:

Brexit: When Britain withdrew from the EU, it raised fundamental questions about the union’s role and purpose. The Union’s cohesion was shaken, and ‘Eurosceptic’ voices in other countries have since become much louder.

Rise of Trump: Trump broke from decades of precedence in his first term, when he questioned the extension of America’s security umbrella over Europe. While this security cover hasn’t been withdrawn, it has caused a lot of uncertainty in Europe.

COVID-19: While the COVID-19 pandemic devastated the entire world, Europe was one of the worst-hit regions in the world — especially in its early years. The economic and political impacts of the pandemic are still being felt in the continent.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: When European pushed back against Russia’s Ukraine invasion, it severed Europe’s access to cheap energy. Energy costs in Germany, today, are 3-5 times higher than in the US.

As Europe struggled to emerge from these crises, the world had shifted. Many of its natural advantages had disappeared. It no longer had cheap energy, making its industry uncompetitive.

It no longer had the certainty that America would protect its borders. Instead, this dependence had become a problem. For instance, the United States was able to bully ASML — a crucial player in the chips supply chain — into cutting itself from China.

There was also a broader geopolitical shift. The neoliberal consensus had withered. Trade protections were propping up all over the world, and the other global superpowers, the US and China, were adopting muscular industrial policies.

Europe’s problems were suddenly impossible to deny: the continent was no longer as pivotal as it once was for international trade.

Europe’s deep malaise

This is where Europe finds itself today.

Many of the region’s key economies are struggling. Germany is in recession. France, caught in a political deadlock, is seeing growth falter. Austria’s economy shrinks amidst political crises, while Belgium and the Netherlands experience sluggish growth due to labor and energy shortages.

Its main economic engines have eroded. Europe once led the world in advanced engineering and automotive manufacturing. China has now leapfrogged the continent. Germany’s auto industry, for instance — once the envy of the world — faces a make-or-break year ahead.

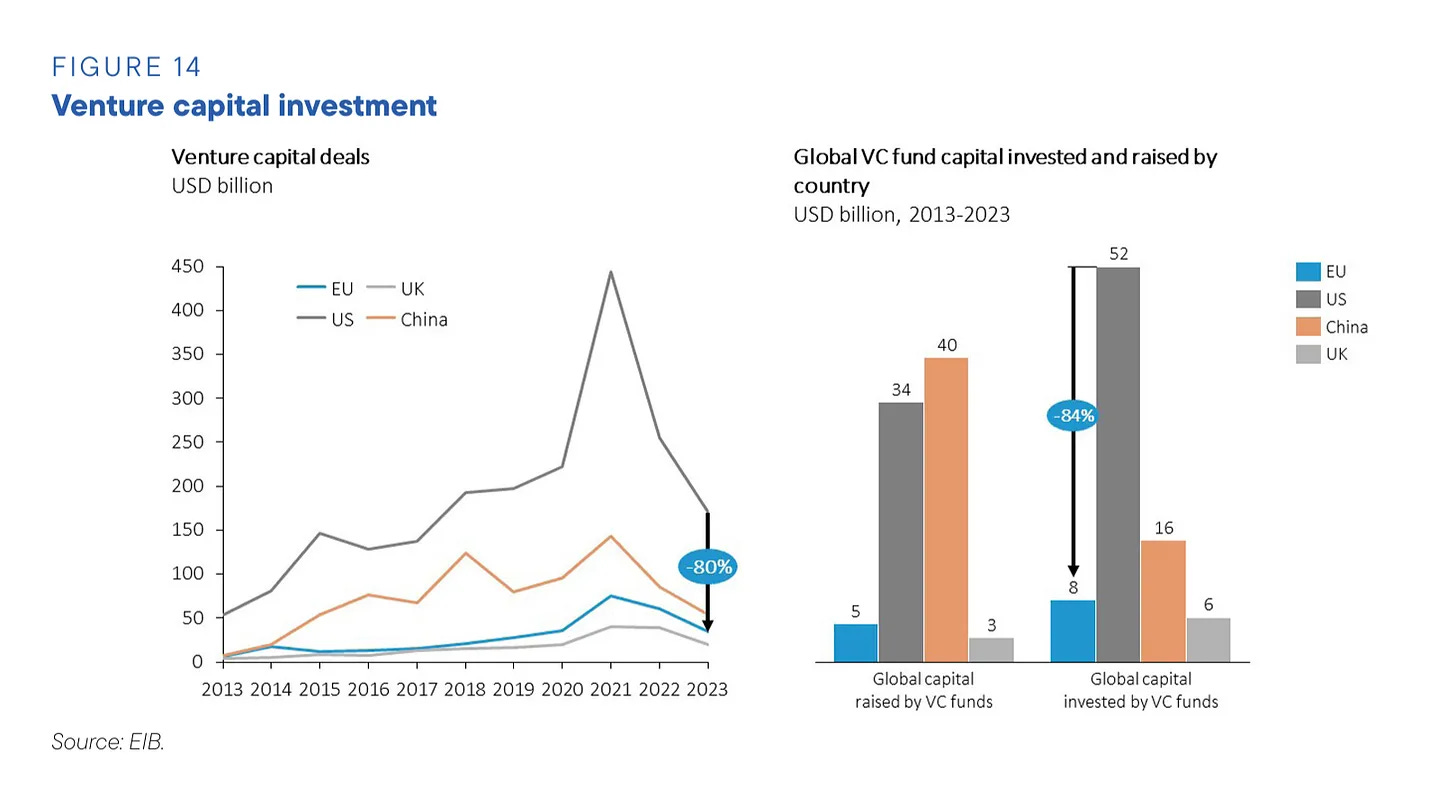

Venture capital investors no longer look towards Europe for new, innovative firms.

The best of Europe’s talent is shifting to the United States, and many of its manufacturing giants are moving production to the US.

All of this calls for a major re-think. However, there’s little hope for that happening. The continent’s two anchors, France and Germany, are in severe economic and political turmoil. Germany is reeling from the shock of losing its industrial base to China and the United States. France’s fiscal mismanagement has put it in a place where it can’t seem to pass a budget. Both are stuck in severe political deadlocks. They’re unlikely to provide regional leadership any time soon.

Things rarely go on forever

For all these reasons, most of the world is deeply pessimistic about Europe’s medium-term prospects.

But that doesn’t mean the continent can be written off just yet. There are industries that it did successfully safeguard — from aerospace, to pharmaceuticals, to green technology — and these retain their global importance. Last year’s medical sensation, Ozempic, was a product of the European pharmaceutical giant, Novo Nordisk. The continent remains capable of more such surprises.

Ironically, while many of Europe’s champion economies struggle, the very countries that were hit the hardest by the Eurozone crisis — Portugal, Greece, Italy and Spain — have now become economic bright-spots.

Europe survived the Eurozone crisis because of the Italian economist, Mario Draghi. Draghi was appointed the President of the ECB when the crisis struck, and he famously said he was “willing to do whatever it takes” to pull Europe out. And he did — from debt restructuring to prolonged negative interest rates. It worked; Europe survived.

Last year, he was brought in again, to suggest a new roadmap for Europe during these troubling times. He published a 300+ page report in September, diagnosing Europe’s problems and suggesting a package of reforms — which covered everything from investments into AI, to skilling, to improving governance. As a whole, it pushed for a more united, cohesive Europe — that could survive an unstable global landscape, and act with the kind of muscularity the rest of the world was moving towards.

There are some indications that Europe is listening. Some of Draghi’s recommendations have already been included in the European Commission’s next five-year agenda. The body’s currently considering an omnibus package that would simplify corporate reporting requirements.

Will any of this actually work? Well, it’s certainly not going to be easy.

That said, only a fool would completely count the world’s third superpower out.

Sanctions, Oil, and India’s Game Plan

When the United States slapped fresh sanctions on Russian oil earlier this month, it raised some eyebrows, especially in India, where Russian crude now makes up over a third of the country’s total imports. These sanctions are aimed at disrupting Russia’s oil revenues—by targeting producers, tankers, and even insurers—but for India, it’s another test of how skillfully it can navigate an increasingly complicated energy landscape.

Hardeep Singh Puri, Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas, however, wants to reassure everyone: “No need to panic,” he says. Speaking to NDTV Profit in an interview, Puri emphasized that India’s energy security remains intact.

There’s plenty of oil in the world, and India is better positioned than most to secure its share.

To understand the fuss, let’s break it down. The U.S. sanctions, introduced on early in Jan this year, don’t just restrict Russian oil exports—they go after the logistics of how that oil reaches countries like India and China. This includes blacklisting tankers and insurers tied to the so-called “shadow fleet” Russia uses to transport its crude. The goal is to squeeze Russian revenues further, making it harder for Moscow to fund its war in Ukraine.

The catch for India? These new sanctions complicate the availability of discounted Russian oil, which has been beneficial for Indian refiners since 2022 due to its lower cost. India started buying Russian oil in ‘22 only because it was really cheap and has nothing to do with India’s relations with Russia. Puri put it bluntly: “If Russian oil is available at good discounts, we will buy it. If it’s not, we will buy elsewhere.

We buy oil from wherever we get it at the cheapest price”

We covered the whole backstory of this in one of the recent episodes titled US sanctions on Russia make things tough for India.

Recently, the Directorate General of Shipping extended approvals for Russian insurers whose name are extremely hard to pronounce, allowing them to cover tankers carrying Russian oil into Indian ports. This bypasses Western insurers who are now under sanctions. It’s a clever move that keeps the supply chain flowing, at least for now

However, the U.S. has set a deadline: sanctioned Russian tankers can only offload their oil in India by February 27, leaving refiners scrambling to finalize deals before that date. Beyond this, India will need alternative shipping arrangements. But Puri remains unfazed. “The global oil market is not in a state of scarcity,” he said, pointing to increased production in countries like Brazil, Guyana, and Canada

One of the most significant issues tied to Russian crude is its impact on gross refining margins (GRMs)—a key metric for refiners that measures the profitability of turning crude oil into finished products like petrol and diesel.

Russian crude’s discounts are shrinking (from $8.5 per barrel last year to just $3-$3.5 now), alternative supplies like Middle Eastern crude don’t offer the same profitability. BPCL’s Director of Finance, Vetsa Ramakrishna Gupta, recently revealed that Russian oil, which accounted for over 30% of BPCL’s refining mix last year, will likely fall to around 20% by March. Gupta also pointed out that declining discounts are adding pressure to refining margins, forcing Indian refiners to reassess their sourcing strategies

But the Oil Minister still seems optimistic. He mentioned that, “Our refining capacity is growing rapidly. We’re investing ₹80,000 crore to expand it, ensuring that we’re prepared for shifts in the global oil market.”

Puri pointed to India’s growing exploration capabilities and its partnerships with global players to boost domestic production. “Petrobras is working with Oil India on offshore surveys in the Andaman Sea. BP is partnering with ONGC to rejuvenate old wells in Bombay High,” he said. These efforts, combined with expanding refining capacity, are aimed at reducing India’s dependency on imports and bolstering long-term energy security.

One of the most striking points Puri made was about India’s unique leverage in the global oil market. Unlike some countries struggling to pay for their imports, India’s strong economy and ability to pay upfront make it a preferred buyer for oil exporters. “This is a buyer’s market. We have demand, and we can pay—unlike many countries that are struggling financially,” he said.

He also said a few other things that were quite interesting. Reflecting on the broader dynamics of the global oil market, he pointed to emerging suppliers like Guyana and Argentina as examples of how new sources are reshaping the landscape. Guyana’s story, in particular, stood out. “They drilled 16 wells with no success. The 17th well hit the jackpot—oil and gas. And that’s just the beginning. There are many other Guyanas waiting to be discovered,” he said. Argentina, too, has joined India’s import basket, marking another step in India’s strategy to diversify its sources. “We’ve gone from sourcing oil from 27 countries to 39. With Argentina coming on board, that number will only grow further,” he added.

This focus on diversification also ties into India’s green energy transition.

While the shift to renewables is inevitable, he emphasized that it’s not a process that happens overnight. “The green transition is critical, but it has a wind-in and wind-out period. You don’t just switch from fossil fuels to renewables,” he said. At the same time, he acknowledged that India’s oil demand is unlikely to peak anytime soon. “Even the most conservative estimates suggest our demand will continue to grow until at least 2040, and possibly 2050,” he noted.

For now, India’s strategy remains clear: continue to secure affordable oil from diverse sources, expand domestic capabilities, and prepare for long-term energy needs. As Puri put it, “Conflicts don’t last forever, but even if they do, we will navigate around them.”

Tidbits

The FMCG sector faces rising input costs, with crude palm oil prices up 40% YoY and tea prices up 24%, squeezing margins. Rural demand grew 5% YoY, but urban demand lagged at 0.5%, reflecting inflation’s impact on consumption and profitability.

India's Composite PMI fell to 57.9 in January 2025, with services slowing to a 26-month low while manufacturing hit a six-month high of 58.0. Strong job creation provides a silver lining, but high inflation and competition challenge the service sector's outlook.

China's January manufacturing PMI fell to 49.1, its lowest since August 2024, as weak domestic demand and unemployment weigh on growth. Despite a $1 trillion trade surplus in 2024, export reliance and geopolitical tensions threaten recovery.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

great writing!

But you forgot demographics in Europe's decline! That's a huge problem for them in the coming decade. Immigration won't solve it, cause it clashes with their pissed off local population.