India’s state discoms are at the cusp of a big change

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s state discoms are at the cusp of a big change

The new age of trade

India’s state discoms are at the cusp of a big change

A new Draft Electricity Amendment Bill is making its way through the system. The changes to the original bill are almost entirely targeted at just one section of India’s power grid, which is also the weakest: the state-owned power distributors, or discoms.

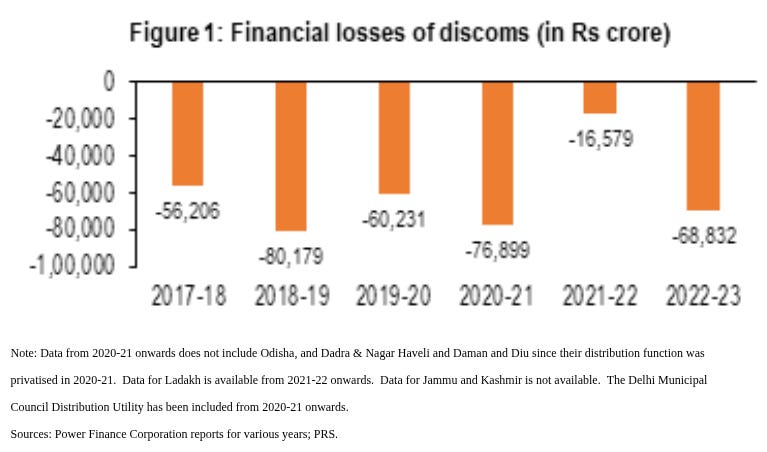

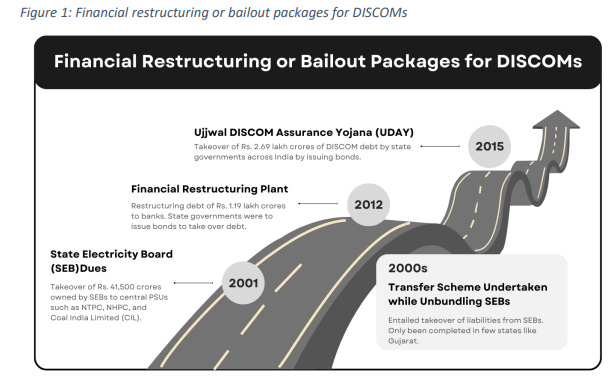

The last mile that delivers electricity from the plant to your home remains a chronic money pit. State-owned discoms have accumulated over ₹6.77 lakh crore in losses by 2022-23, growing at ~7% annually since 2015. To fund these losses, discoms have been taking on debt, which crossed over ₹7.5 lakh crore last year. Yet, the losses continue, and discoms get stuck in a loop of raising new loans to service older debts.

As a result, the government is forced to repeatedly bail them out.

These losses reverberate across the entire power ecosystem. Much needed infrastructure investments get delayed, while generators often don’t get paid on time. And consumers suffer through unreliable power supply and tariffs that never quite make sense.

The draft bill attempts to address this by targeting four structural friction points that have plagued discoms for decades. These aren’t bugs in the system — they emerged for reasons that may be valid. But these features have now turned into distortions that need repairing. Understanding them might explain why your electricity bill looks the way it does, or even why reforms keep stalling.

Let’s break them down.

Power procurement

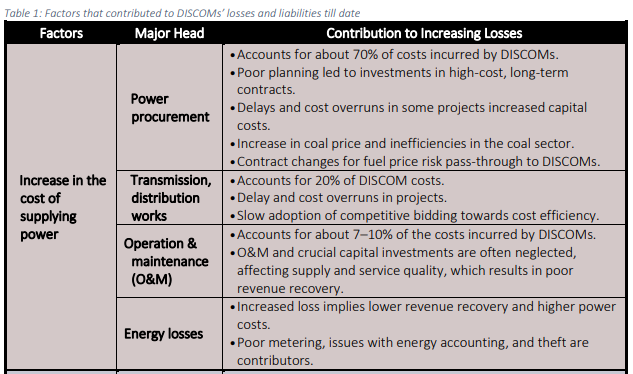

A state discom’s job sounds simple: buy power from generators, deliver it to consumers, and collect payments. But it’s not the delivery of power where they’re most inefficient — it’s the buying part.

In fact, procurement makes up 70% of the costs of a discom. Effectively, the biggest reason for why discoms run heavy losses can’t truly be controlled by them. To understand why, let’s break down into how they procure power.

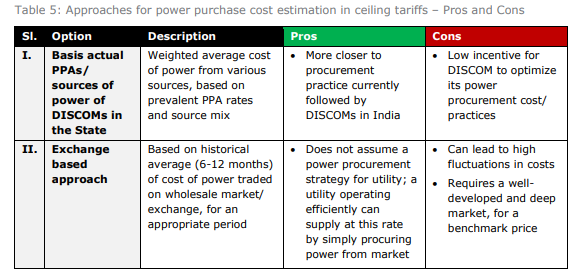

See, discoms buy power from generators (typically coal plants) through Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). These long-term contracts are usually 20-25 years long, and include fixed capacity charges that don’t really change over time, along with some variable costs. So, even as operational efficiencies improve, these contracts don’t adjust prices much. Because of that, a coal plant built in 2012, for instance, might be charging similar prices even today.

As a result, discoms are often forced to buy expensive legacy power even when cheaper alternatives, like solar, wind, or even short-term market purchases, are available.

Additionally, these PPAs are take-or-pay contracts, where payments must be made regardless of whether the power is actually used. This causes problems in situations where power demand has clearly been overestimated. For instance, if a discom signed a PPA expecting demand to grow 8% annually, but demand only grew 4%, it will still pay for unused capacity. These fixed costs run into thousands of crores annually.

On top of that, when energy prices get higher due to a crisis, the generator passes on the extra costs to discoms. Also, power procurement is affected by the capex undertaken by power generators, which can often be inflated. This, in turn, raises the fixed prices faced by discoms.

Inflexible pricing

The second friction relates to how discoms set the prices you pay. To a degree, we covered this earlier in our primer on how Indian power prices work. But we’ll summarize it quickly here.

Discoms follow a “cost-plus pricing“ system, which is regulated by the local State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC). They calculate their costs (most of which is defined by procurement), and add a return on capital which is set by the SERC, and that becomes the tariff. In theory, this should guarantee cost recovery. In practice, though, the effect has been different.

For one, without penalties for not meeting certain benchmarks, the cost-plus model doesn’t incentivize efficiency. If a discom can pass through its costs anyway without consequences, why would it want to reduce them? Losses due to transmission or poor collections are likely to get baked into future tariffs with a regulatory lag, rather than eliminated quickly. However, this has been slowly changing, with discoms getting more efficient lately.

The second issue, though, is mostly out of the discoms’ control. Power is a politically-sensitive topic, especially during elections. So discoms find it extremely hard to pass on any costs passed on to them further to households. The gap between what it costs to supply power and what consumers actually pay gets recorded as a “regulatory asset“ — essentially an IOU to be recovered from future ratepayers. These regulatory assets have ballooned to lakhs of crores across various state discoms.

This system of setting tariffs becomes even further complicated due to the friction between the Centre and state governments on electricity as a subject. In India, electricity sits on the Constitution’s Concurrent List — both Centre and states can make rules on it. This makes reform a pretty hotly contested space between the two.

Each state has its own discom and has iron-hand control over it. Regulatory commissions, though nominally independent, often reflect state government preferences. If the Centre tries to push for cost-reflective tariffs but a state government wants to promise free power, it’s usually the latter that wins out.

Some states have even gone years without any upward tariff revisions, simply rolling over losses. However, at the same time, they’ve often delayed subsidies that were earlier promised to discoms in order to make up for these losses. This puts discoms between a rock and a hard place that they find it hard to get out of.

The cross-subsidy squeeze

The third friction is related to the various consumer bases of discoms, and how some of them subsidize the others.

Broadly, discoms have two separate sets of consumers. On one hand, you have households and farmers, who require cheap power. On the other, you have commercial & industrial (C&I) consumers who run shops and factories, as well as the Indian Railways. In many states, the latter set pays ₹10-12 per unit (sometimes more), while the actual cost of supply is around ₹7-8. The difference is used to subsidize households and farmers.

This has long been a rule that India’s power sector has followed. The logic of this was equity: essential sectors and vulnerable groups shouldn’t bear the full cost of power.

However, this system is now slowly turning unsustainable. C&I consumers are increasingly opting out of these high tariffs. Instead, they’re procuring power from third-party generators directly. In fact, the Green Energy Open Access Rules (2022) have allowed factories to generate their own power supply — India now has 79 gigawatt worth of industrial power generated captively. Every time a high-paying customer leaves, the cross-subsidy pool shrinks.

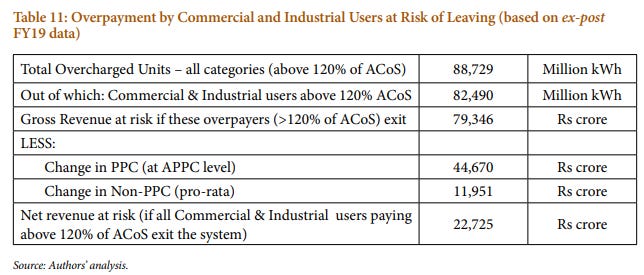

Now, how much does this cross-subsidization matter? Well, it is true that commercial customers make up quite a small chunk of discom sales. However, much of this volume shortfall is made up for in value. As per the CSEP’s assumptions, in 2023, the net amount at risk if all overpaying commercial users leave was over ₹22,700 crore. And most industrial consumers, it seems, have already made the move away from discoms. So, discoms are left depending heavily on their low-revenue customers.

Besides these three, there are other inefficiencies within discoms. For instance, losses due to transmission are quite sizeable — we’ve covered this earlier. But these are the three major friction points that the bill aims to tackle — and that’s what we’ll be discussing next.

The policy response

One of the biggest changes in the new bill is introducing private competition. It allows multiple distribution licensees to operate in the same area, using shared infrastructure. A new private entrant could procure power more efficiently, and offer consumers better prices, pressuring discoms to optimize. The bill also hopes to introduce new, more flexible market instruments beyond the standard PPAs.

However, this idea is also one of the most scrutinized. A major concern is that if most of the costs come from power generation, how effective will competition within discoms be in reducing the rest? In fact, in many Western countries, attempts to introduce competition within discoms have generally yielded mixed results.

Additionally, this type of parallel licensing has been tried before in small pockets (like Mumbai), but ran into network duplication issues. It could be far more efficient, the argument goes, to have just 1-2 operators — or look to introduce competition in other forms.

Additionally, the bill allows SERCs to exempt their discoms from the Universal Service Obligation (USO), if they want. The USO mandates discoms to supply electricity to all customers who ask for it — including high-powered industrial consumers. For that, the discom has to procure more power, thereby signing a PPA. However, this new change hopes to do away with that burden for consumers who use more than 1 MW of power. With industrial users moving towards securing power from other sources or even captively, this rule is timely.

The bill gets aggressive on tariff-setting. It empowers the SERC to revise tariffs if discoms don’t file petitions on time. Ideally, this should prevent massive delays from the discom side, and instead ensure that the new, cost-reflective tariffs are applicable starting the next financial year. The era of rolling losses into regulatory assets should, in theory, end.

On that note, the bill also streamlines power between regulators, state governments, and the Centre. For one, the bill hopes to create an Electricity Council, which aims to reduce friction between the Centre and states on electricity. Think of it as a GST Council for electricity.

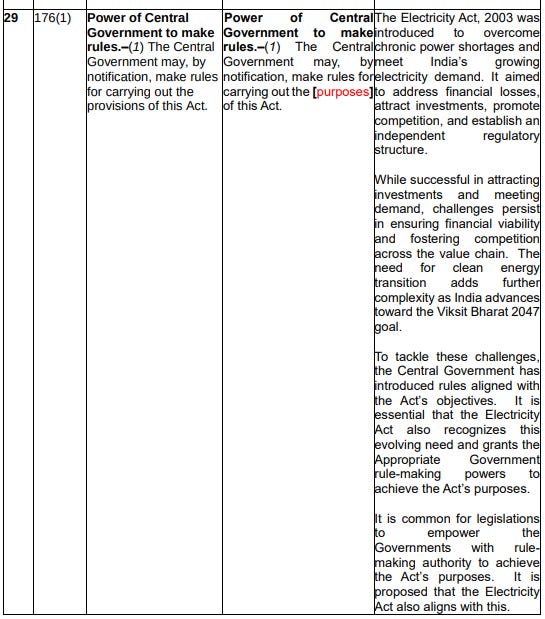

But this is also where things get controversial. On paper, the bill empowers the Centre to throw out members of a SERC if they “willfully violate” the Act. Determining such a violation can often be subjective, and therefore open to abuse. Additionally, as per Section 176, it also allows them to set the rules of the Act going forward as per their whims. These two rules can damage the independence of regulators, while potentially centralizing power to an extreme.

Lastly, the bill is doing away with industrial cross-subsidies gradually over the next five years. Given that industrial consumers are leaving the grid (taking their subsidies with them), this makes sense. For farmers and low-income households, subsidies will continue, but will be drawn from the state budget instead of hidden tariffs. This, the government hopes, will reduce the costs of rail freight and improve the competitiveness of our MSMEs.

Beyond these areas, the bill importantly mandates that discoms procure a minimum share of their power from renewable sources — flouting which can result in penalties. It also establishes universal service standards for reliability and quality, formally recognizes energy storage systems under the Electricity Act, and so on.

Conclusion

The Draft Electricity Amendment Bill encompasses procurement rigidities, tariff distortions, cross-subsidy unsustainability, and federal friction in one legislative package. That’s extremely ambitious.

However, this ambition doesn’t come without concerns. For one, there is plenty of uncertainty on whether the bill’s competitive framework will function as intended. Secondly, there is a fear that the changes proposed could raise prices significantly for the average Indian. There is also a hesitation that the bill overcompensates the Centre with too many powers — some states have indeed expressed their dissatisfaction with the bill.

It is certainly still a work-in-progress. But there’s no denying that, any which way, India’s power distribution direly needs changing. Our electricity future hangs on whether this intent translates into the right kind of change.

The new age of trade

2025, as you’ve probably heard a thousand times so far, was the year global trade seemed to fall apart.

The year saw the United States mount a far-reaching, world-wide tariff war, along with a series of other trade restrictions. As others responded, globally, the level of trade restrictions reached a point it hadn’t in decades. Trade networks developed over decades abruptly fell apart. Earlier this year, you could be forgiven for wondering if we were entering a phase of deglobalisation — where countries would retreat from international trade, and their businesses would only serve their own consumers.

That isn’t what happened. Although this has been a major stress-test for the global economy, the system hasn’t collapsed. Instead, it has adapted to its new constraints, bending and re-routing to meet new challenges.

Every year, a team of global economic organisations, including the World Trade Organisation and the Asian Development Bank, publishes a “Global Value Chain Development Report”. The report looks at how global value chains have changed in the preceding year. Naturally, this year’s edition — a 450+ page behemoth — has a lot to chew on. Its message, though, isn’t altogether pessimistic.

We can’t cover every detail the report goes into, but here are some things that caught our eye.

How 2025 has moved the global picture

The big, global economic story of the last few years is one of fragmentation.

A decade ago, the world felt like it was slowly turning into a single, large, global economy. But since 2018, that picture has been collecting fractures. Starting with the first US-China trade war, geopolitical rivalries began spilling into the domain of trade. While countries are still trading across geopolitical lines, the amount of such trade began to decelerate.

The worst episode, according to the report, came in 2022 — as many trading ties broke once Russian troops marched into Ukraine. Things stabilised, briefly through 2023 and 2024, but the first half of 2025 re-accelerated that fragmentation. The year saw the world’s largest trading partnership — the United States and China — pulling apart faster than ever.

But crucially, this doesn’t signal an end to global trade.

Trade adapts

When old trade links break, the bilateral trade between countries naturally wanes. For instance, when the United States ramps up trade barriers on countries like China or India, it imports less from those countries. Similarly, if Europe cuts its oil purchases from Russia, they trade less.

And so, some features of the globalised world we once knew have already disappeared. Europe, for instance, severely curtailed its reliance on Russia for its energy needs — reversing a trend that began with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

But lower trade between some countries isn’t the same thing as reduced globalisation.

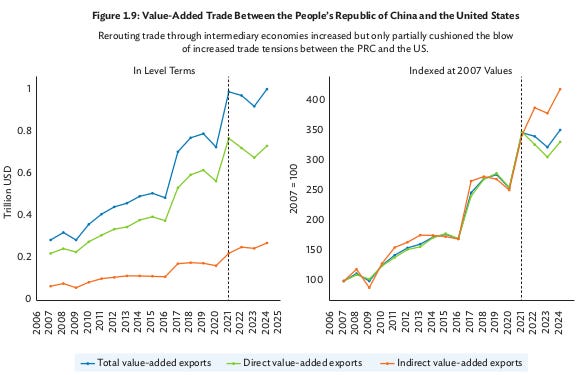

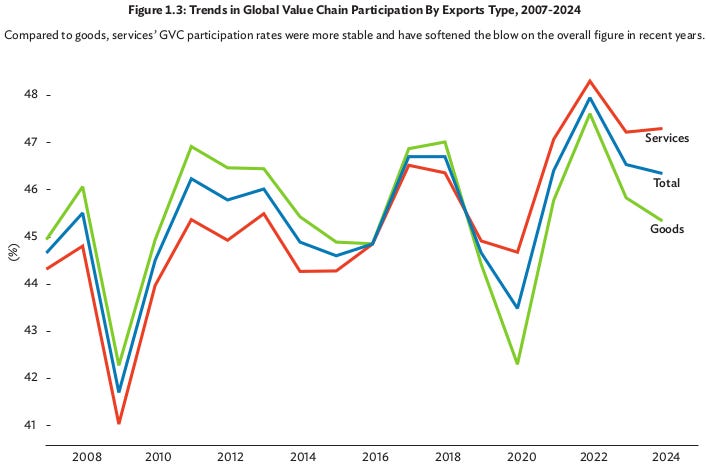

The broader model of global value chains — of large, international production networks where different tasks are performed in different countries — is almost untouched. At its peak, in 2022, 48% of world trade happened through global value chains. Now, it’s declined to 46.3%. For all the chaos of the last few years, globalisation is functionally untouched. It’s close to the highest it has ever been.

Instead, global value chains are adopting new forms. The biggest such adaptation, perhaps, is the rise of “connector economies” — like Mexico and Vietnam. We’ll get back to that soon.

Services now lead globalisation

There are some facets of globalisation that have almost been unaffected in the recent chaos. While goods trade has been difficult in some quarters, trade in services — especially digital ones — continues unabated.

This shift has been in play for a while. In fact, over the last five years, services have consistently been the most important component of global value chains. Many — especially those like finance, or information technology that are delivered through the internet — have also been more resilient than goods in the face of shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the world sours on goods trade, services could become a shock absorber.

What to expect in this new world

That said, the fact that globalisation isn’t dead is probably no surprise to you. If you’ve followed us for a while, you probably also realise that businesses and economies are endlessly flexible, and routinely find ways out of impossible-looking situations.

The more interesting question is: what are the specific adaptations they’re coming up with in a time like this?

An era of connector economies

The fragmentation we’re seeing, today, has a common feature: countries that consider themselves geopolitical rivals are beginning to see the direct trade between themselves fall. The report explores global “blocs” based on their UN voting patterns, and finds something interesting: since 2017, trading activity within a bloc has grown by roughly ~4% faster than it has across blocs.

The starkest example of this lies between the US and China. Since 2018, when their trade war began, their trade with each other has grown ~30% slower than their trade with the rest of the world.

These global divides aren’t absolute, however. The fact that the US and China are de-coupling doesn’t mean that all their trade partners are de-coupling as well. Quite the opposite: many countries are successfully positioning themselves between feuding nations. In doing so, they can become “connectors” — conduits through which goods flow between countries that don’t see eye-to-eye.

For instance, until 2024, Mexico turned itself into a conduit for Chinese goods to enter America — becoming its largest trading partner. Similarly, Kazakhstan helped a heavily-sanctioned Russia buy goods from the world. In 2022, once Russia was technically cut off from European markets, its imports from Kazakhstan went up nearly 83% — just as the latter suddenly stepped up imports from the EU.

This doesn’t mean connector economies are blindly re-routing goods from one country to another. More commonly, they’re stepping into small roles in the value chain — like assembly, or packaging. Becoming a connector, it appears, could be the first stepping stone into integrating oneself into a global value chain.

Investing in resilience

There’s another side to this though. As uncertainties rose, many businesses began blindly diversifying to suppliers from other countries. According to one survey, in 2022, 62% of enterprises tried changing their supplier base.

Ultimately, however, many of these changes turned out to be entirely cosmetic. While the medium country substantially increased the number of trading partners, the number of their meaningful trade relations — partners with more than a 1% trade share — barely changed.

As the report explains, it only makes sense to diversify to a new trading partner if they’re less brittle than what came before. This is why narratives like “China+1” don’t automatically result in new business opportunities. Other economies need to be ready to meaningfully replace old suppliers.

The report introduces a new framework to evaluate potential suppliers — which it calls the “Global Value Chain Readiness Index”. We won’t go into the index here, but the key insight is this: a good replacement supplier should have everything from good connectivity, to short customs clearance times, to easy permitting, to access to financing. Without that sort of readiness, the opportunity doesn’t really exist.

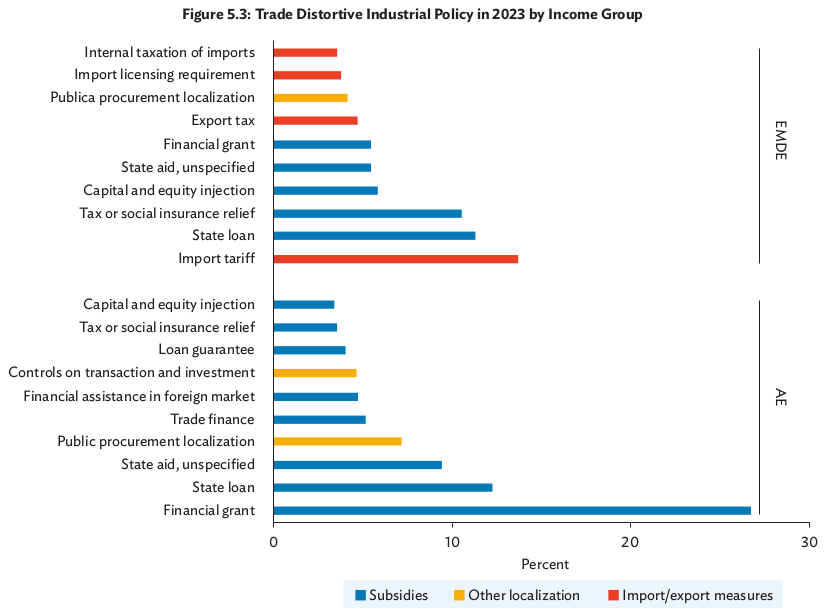

Industrial policy

The current spate of uncertainty has, for many countries, felt like a crisis. Many have responded through industrial policy. As trade relations break down, there’s a rush to on-shore the production of important things — chips, green technology, batteries, and the like — through generous incentives. The report notes that recent industrial policies have been unprecedented in their scale and scope, especially as the WTO has grown weaker.

It’s hard to really know how to even understand the impact of these policies. Modern economies are simply too complex. Here’s one example: some time ago, China started subsidising its local ship-building industry, even though it was far more inefficient than its competition in Japan and Korea. As these government-backed Chinese builders began crowding out their rivals, the global price of ships fell, making shipping ~6% cheaper. That was unexpected good news for China — as the world’s biggest manufacturer, cheaper shipping meant that other Chinese exports grew by ~5%.

Funnily, every dollar of subsidy they gave only generated ~18 cents of profit for Chinese ship-builders. As industrial policy for ship-building, the returns are mediocre. But it gave a lot of business to Chinese manufacturers, and their customers abroad. Did the policy succeed, or fail?

Targeted trade deals

There’s an interesting, somewhat counter-intuitive outcome of the global uncertainty: the number of trade deals have increased. These aren’t the broad, all-inclusive deals that happened before, where countries would try and set the overall terms of trade between themselves. Instead, these are narrow agreements that target something very specific: like cooperation in critical minerals, or technology. In the last five years, the number of critical minerals related deals have gone up ~15x. The number of digital trade agreements, over the same period, have gone up ~35x.

These deals are less ambitious than the sweeping trade agreements countries would aspire for. And that means their effects are very different.

For one, many of these are hastily patched together. They often don’t have any binding commitments at all. In practice, unfortunately, that sometimes means these deals generate very little trade.

The most successful of these deals are between entities that already have strong trade ties, and whose economies are already meshed into each other. If the countries signing a deal already have a regional trade agreement in place, the new deal is more than 8 times more likely to succeed. This has an interesting outcome: as countries that trust each other grow closer ties, the global economy can come to resemble a patchwork.

Where does India sit?

There are a lot of themes the report covers, and there is much that we haven’t gotten to. Before we leave, though, we wanted to run through a few things it says about India:

India has broken into the world’s top ten countries, in terms of the value they add domestically to their exports. Roughly 2.8% of the value added in the world’s export basket comes from India. Much of this is on the back of our services exports.

The WTO does a detailed assessment of India’s readiness to take on global value chains, and our performance varies wildly across criteria. For instance, we’ve been rated highly for our financial reserves, or for our logistical performance. Surprisingly, the report even assigns us Rank 1 on its “business climate index”. Meanwhile, we do exceptionally poorly on many criteria — including the capacity of our firms, our energy infrastructure, and our financial depth.

The report also recognises India as one of just sixteen countries it studied where global value chains are persistently lengthening — that is, we’re one of the few parts of the world that is steadily taking on deeper and more complex parts of global production.

Tidbits

JSW Energy to Build Wind Turbine Blade Plants: JSW Energy is setting up wind turbine blade manufacturing units in Gujarat and Karnataka, expected to produce 700–800 blades annually. The facilities will serve both JSW and its Chinese partner Sany Renewable Energy.

Source: ETJP Morgan to Build Asia’s Largest GCC in Mumbai: JP Morgan will occupy a 2 million sq ft facility in Mumbai’s Powai by 2029, housing 30,000 employees. This will be Asia’s largest global capability centre, backed by a $1 billion investment from Brookfield.

Source: BSKushner’s Affinity Partners Exits Warner Bros Takeover Bid: Jared Kushner’s Affinity Partners has withdrawn from Paramount’s $108.4 billion hostile bid for Warner Bros Discovery. The studio’s board is expected to reject the offer, favouring Netflix’s $82.7 billion deal instead. We recently covered the economics of this whole deal on The Daily Brief.

Source: BS

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉