Some strange things are taking over Hollywood

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Hollywood gets rumbled by Silicon Valley

Too much solar, too little storage for India

Hollywood gets rumbled by Silicon Valley

It was a plot twist even screenwriters would struggle to script.

Earlier this month, Warner Bros (WB) — the century-old creator of Looney Tunes, producer of the Batman movies, the Harry Potter franchise, and countless other beloved films — invited bids for the sale of its iconic film studio and streaming business. Netflix, the tech-enabled upstart that Hollywood (apparently) secretly hates, emerged victorious with a $72 billion bid.

A couple of days since, though, the result no longer looks certain.

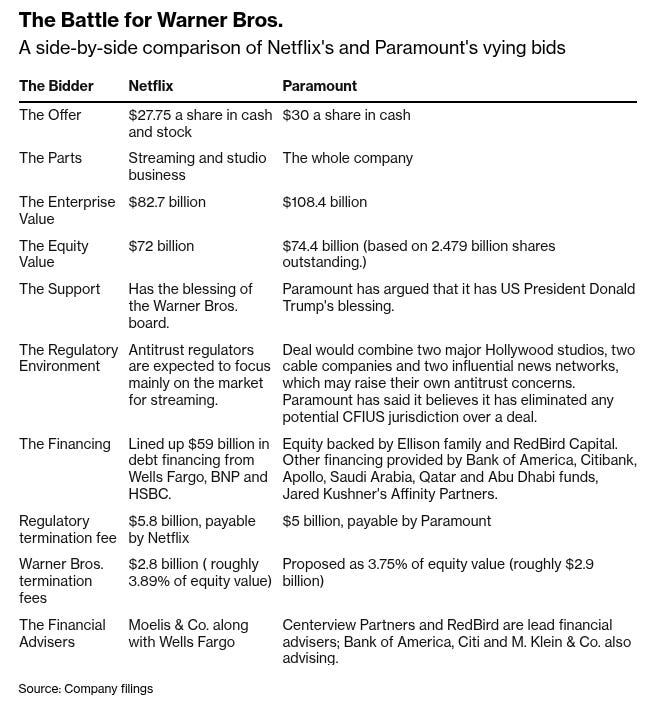

Their winning bid was quickly challenged by another bidder, Paramount-Skydance (or PSKY) — which produces the Mission: Impossible franchise. Backed by financier Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law, and the sovereign wealth funds of Saudi Arabia and Qatar, PSKY announced a hostile $108 billion counter-offer for all of WB’s business. It’s an all-cash offer, which seems to give investors more bang for their buck than Netflix.

At the moment, both suitors are loudly making their own cases. PSKY’s CEO, David Ellison claimed that his bid was “creating a stronger Hollywood,” with fewer job cuts, and more focus on creators. Netflix’s co-CEO, Ted Sarandos, brushed off the move as “entirely expected,” but appeared confident of closing the deal.

WB’s, now, is a cliffhanger. This moment perfectly captures the storm engulfing the big, old Hollywood studios that, in their heyday, made the most popular movies in the world. To us, this is an excuse to understand the current state of an industry we haven’t dug into before: show business.

Let’s roll.

Creativity is risky

The movie business comes with no guarantees. There is no way of knowing, in advance, if a story will really capture the hearts of people. For every success, there’s a graveyard of failures. You could pour hundreds of millions into a story you think has to be told — only to see it go down without a flutter.

The business is also capital-intensive and slow. An A-list movie can take years and hundreds of millions of dollars in upfront investment. You then spend massive amounts of money on distribution and marketing. For all of that, you aren’t promised a single rupee in return.

That nauseating uncertainty is, perhaps, the cost of trying to create a moment of magic on screen.

Interstellar 4K HDR IMAX | Into The Black Hole - Gargantua 1/2

The industry behaves a lot like venture capital — with each movie like a startup in its own right. There’s no universe where you only deliver hits. You’re just gambling that a few hits will make up for your many losses. You bankroll many, very expensive projects, knowing that they could all flop, in search for that elusive mega-hit.

There are ways to soften this volatility. For instance, studios do everything they can to juice out successful IPs. Take WB’s ownership of Harry Potter — it gave them some hope of steady revenues from its films, as well as non-film sources of revenue like theme parks or merchandise. But that, too, comes with few guarantees.

Unlike many other industries, scale, too, has its limits in the movie business. Simply being bigger, or making lots of movies at once, doesn’t guarantee success. There are few fixed costs that you can successfully spread over multiple productions. Big expenses — like high-profile actors and directors, or distributing and marketing costs — are incurred afresh for each movie. If anything, when properties do work, you end up paying the talent behind those projects more, killing your economies of scale.

This is why classic corporate tactics that pursue scale, like mergers or acquisitions, regularly fail in this industry.

Tech enters the mix

There was one thing that did affect the industry’s economics, though: Silicon Valley. The tech industry came knocking on Hollywood’s doors in two avatars.

Tu-dum

The first type is the streaming platform model, championed by Netflix.

Streaming companies fundamentally changed how content was delivered to customers, by bringing the internet into the picture. It was, arguably, a tech company that happened to work with films. Their product isn’t movies or TV shows, but their platform.

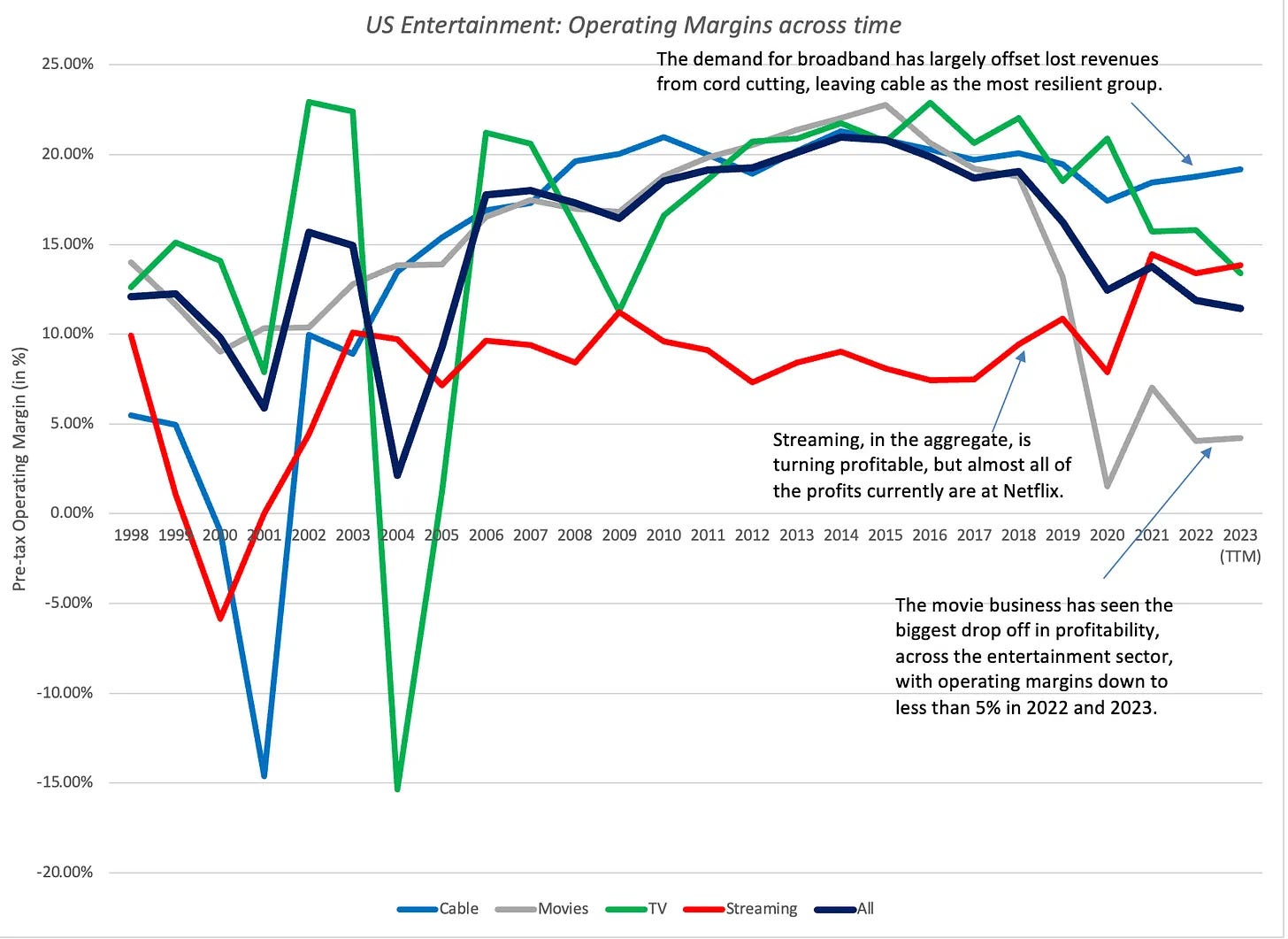

That allowed for very different economics. Like many other software products, Netflix enjoys a stable, monthly subscription revenue. And they created genuine economies of scale — every new customer gives them revenue, while delivering content to them costs almost nothing. And so, uniquely for this business, Netflix could aspire to smooth, low-risk, non-volatile revenue.

But crucially, tech didn’t solve everything.

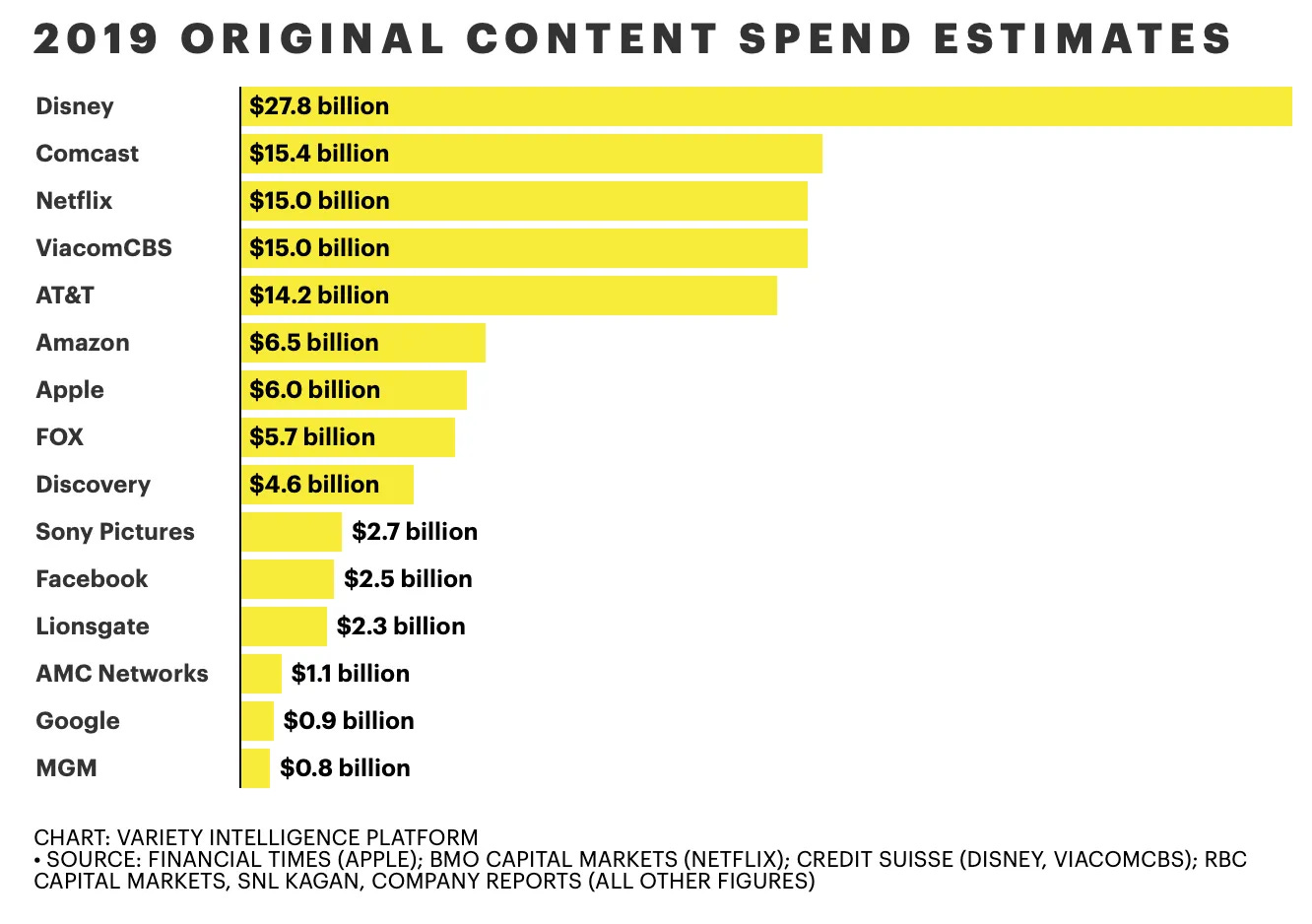

Netflix’s other bet was that it could make it more cost-effective to create content as well. The company thought it could churn out movies and TV shows in huge volumes, and then have an algorithm determine where it should double down, and where it should cut its losses. It began bombarding its customers with shows made to binge — with entire seasons released on the same day to maximize engagement. By 2022, Netflix was outspending almost every traditional studio in production budgets.

The promise of technological disruption, here, fell short.

Other studios, like Amazon’s Prime Video, were learning the same lesson. Amazon could cut costs and achieve scale on the back of its distribution network and cloud infrastructure. For the content for its platform, though, it eventually went old school. For instance, it famously acquired the iconic MGM Studios — which owned the James Bond franchise — for $8.5 billion.

The 21st-century studio

Technology also came for the industry in the form of the tech-forward studio, championed by companies like Skydance — a company founded by David Ellison, the son of Oracle’s Larry Ellison.

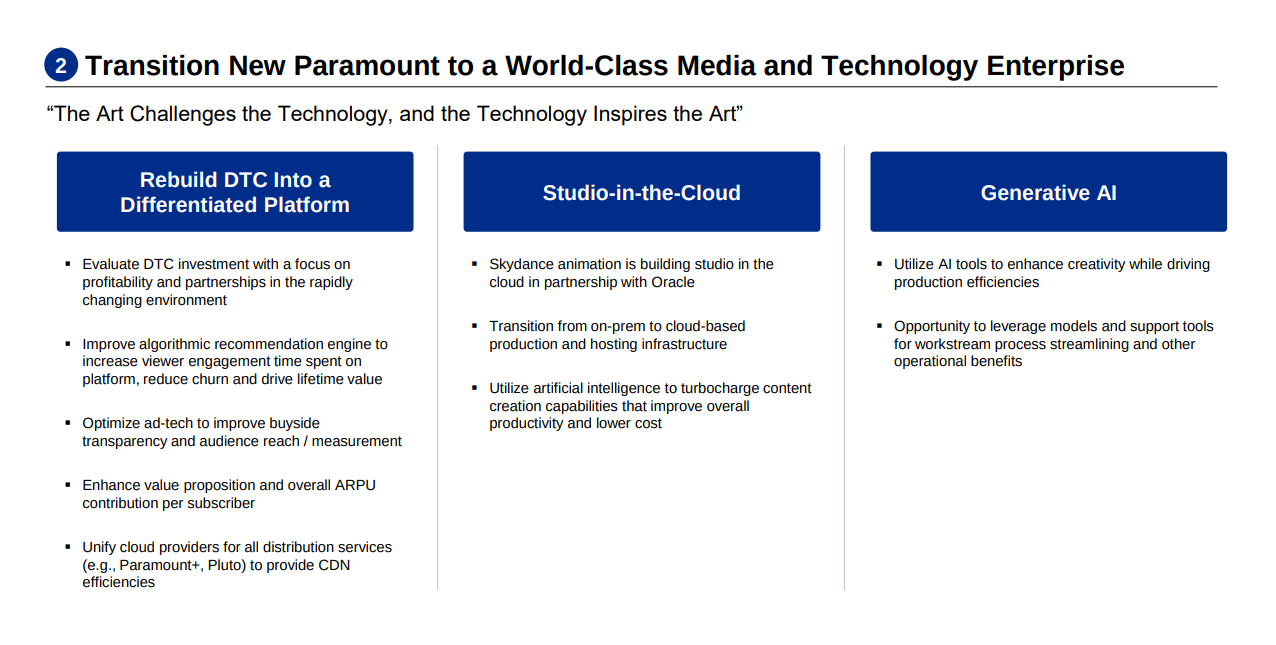

Unlike Netflix, Skydance wasn’t trying to improve distribution. It was bringing technology to film production, incorporating platform-like features in its production workflows. For instance, it’s building a “studio in the cloud” for its animation films, in partnership with Oracle. It also has an advanced advertising-tech stack and a powerful algorithmic system to increase engagement on all its IPs.

This makes it leaner, faster, and more tech-savvy than traditional firms like WB.

Within 2 decades, Skydance had grown large enough to acquire one of Hollywood’s great legacy companies, the 110-year old Paramount, which had made some of the most beloved movies of all time — including The Godfather, Interstellar, and Top Gun.

A passing of the mantle?

As these new disruptors, the incumbents certainly tried adapting to this new era.

Briefly, they even thought they would prevail. Back in 2022, WB’s CEO David Zaslav had bragged that his company was resilient, even as Netflix’s profits were dwindling. He was echoing a wider sentiment. The industry had declared streaming dead, and Netflix’s stock was falling dangerously.

A little more than three years in, though, that statement feels profoundly ironic.

Goliath crumbles

Warner Bros was one of the great giants of Hollywood. But by the early 2020s, its aura had faded. It had seen an entire generation of failed attempts at corporate restructurings. In 2000, for instance, its parent Time Warner went through one of the great mega-mergers of the era, with AOL. That eventually came to be seen as one of the worst corporate marriages ever. Later, in 2018, the telecom giant AT&T bought Time Warner. After years of unbearable costs, they spat out Warner Bros in 2022, merging with Discovery — only to see that fail as well.

Amidst this tumult, WB’s core businesses — traditional cable TV, news channels like CNN, and so on — were declining fast, as streaming became ever more popular. Their legacy IPs, meanwhile, were depreciating in value.

To step up to the challenges of this new era, WB began its own streaming service, HBO Max — much like the other legacy media firms did, to counter Netflix. It looked like a strong showing. The project had some of the best IPs in the business — from Game of Thrones, to Last Week Tonight, to Chernobyl, to Succession.

But where they excelled with their content, they lost the plot elsewhere. The platform was bogged down by poor technical execution. It made strategic mistakes with pricing and branding. Infamously, they changed their logo so often that their own employees were confused. Max failed to make a dent in the market, growing by just 1-1.5% monthly, .

As problems mounted, WBD began making worse mistakes. They tried finding savings through cost-cutting, only to miss the forest for the trees. They gutted potential quality IPs, including near-complete films. That money was fueled into reviving its older, depreciating IPs, which disappointed.

All of this led to a spectacular price crash between 2022-2024.

Shape-shifting

But as WB’s troubles escalated, Netflix dragged itself out of an existential crisis.

Just a few years ago, the company was widely seen as throwing too much money trying to make new inroads into a saturated customer base. But then, it changed tracks dramatically, even doing things it once said it wouldn’t. For instance, after vowing never to do so, they introduced ads in 2022. By 2024, this ad-tier plan had attracted over 70 million monthly active users globally.

Similarly, they cracked down on password-sharing — as you probably experienced yourself. Netflix has said that this move, while controversial, helped get them many more paid users.

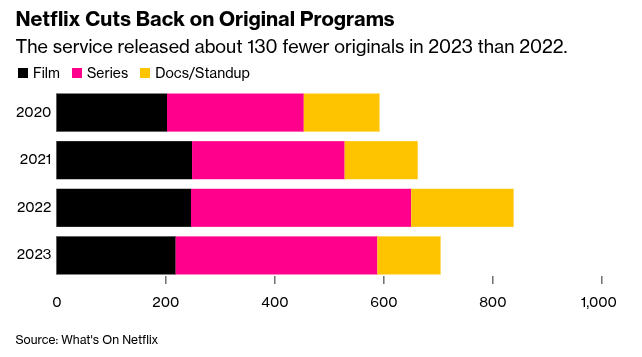

The company also finally began pulling back from its volume-heavy content strategy. Over the years, it had flooded the market with new shows, but had barely created any memorable IPs. In fact, their one-shot “binge” releases meant that even good shows see a small peak in engagement, only to fizzle out. But lately, the company has finally learnt to bend to the unforgiving economics of show business. It’s turning to make fewer, but more high-quality films and TV shows every year. It’s also changing how it releases its TV shows — from dumping entire seasons in one-shot, it is staggering episode releases over weeks.

Even as it was chipping away at those losses, the company’s bets on international content and sports started paying off. The South Korea-based Squid Game became Netflix’s most-watched series, proving that great content could cross language barriers. They also began foraying into live sports, notably getting exclusive rights to the Mike Tyson-Jake Paul fight — which became one of the highest-streamed one-off sport events ever.

By Jan 2025, Netflix had completed its remarkable turnaround, growing to over 300 million subscribers globally. Its market cap rebounded above $400 billion — greater than even Disney’s.

Meanwhile, Skydance was trotting along its path comfortably. It consistently delivered some incredible movies in the past 4 years, including Top Gun: Maverick (which was the highest-grossing movie of 2022) and the last 2 Mission: Impossible films. It was also expanding its slate of animation films.

At the same time, it avoided overspending in the streaming wars, which helped it maintain financial discipline. Unlike WB, it didn’t invest in creating its own streaming platform, and instead chose to partner with other streamers — like with Apple TV+ for exclusive animation releases.

The technology side of things helped a lot. Unlike any other animation studio which works a lot on-premise, Skydance does everything on the cloud, which helps it achieve global scale in film production — something legacy studios could never do, and in a way different from streaming. They’re also using AI and ML in their production workflows. For instance, in a movie with a lot of animations, AI can be used in tracking which assets need to be reused where.

Slowly and steadily, it performed well enough to acquire a huge piece of Paramount in 2024.

Roll credits?

So, does Netflix take over WB? Or does PSKY’s eleventh hour bid bring them the win? We have no idea. It looks like this war might last for months.

No matter who wins, though, it will leave Hollywood a very different entity. As another giant falls, the industry will come one step closer to monopolisation. And it will mark one more win for Silicon Valley in the business of making films. What will this mean? Will productions, for instance, become more homogenous, as they come under the oversight of an algorithm?

It isn’t entirely clear that this deal is desirable for the buyer. After all, Warner Bros. itself felt on top of the world before it went down its path of ruinous M&A. For all you know, acquiring WB could end up being more expensive than the multi-billion dollar offers they’re already making. In fact, Netflix’s shareholders were reportedly unhappy at the prospect of buying a lumbering business like WB.

The climax of this story is still being written, and we have no idea if there’s a happy ending in sight.

Too much solar, too little storage for India

If there’s one thing we’ve learned from the solar frenzy, it’s that you can have too much of a good thing.

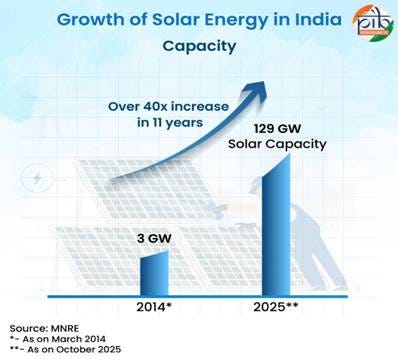

Fueled by government incentives, Indian companies raced to build solar module factories at rapid speed. In fact, we already surpassed our 2030 target of 50% of electricity capacity from renewables. But, this speed has led to a problem — supply of solar power is wildly outstripping demand. India’s solar module manufacturing capacity may shoot past 125 gigawatt (GW) by the end of this year — over 3 times what the country can absorb domestically.

This is causing the industry to brace for a painful shakeout. There is a desperation to sell panels at any price just to utilize production capacity. Margins are shrinking fast, and some module makers have even slipped into the red.

Here’s where things get even more absurd. Even with this over-supply, developers who do want to build new solar farms are finding no buyers for their power. As of September, 44 GW of awarded renewable capacity doesn’t have any power purchase agreements, because no one (especially state utilities) will sign them. That’s nearly half of all projects tendered since FY24!

Utilities aren’t buying because they’re betting on future prices being even lower. Solar tariffs in India have plummeted ~80% over the past decade, and state discoms don’t want to commit now when solar could be even cheaper next year. If you could buy power for near-zero rates in the spot market, why would you enter long-term fixed-price contracts now?

So, how do we break this logjam of too much midday power and no takers? Enter grid-level storage – the hero we need and have talked a lot about. Large batteries could soak up the noon-time solar glut and release it during the evening peak, turning unpredictable renewables that depend purely on sunshine into on-demand power. With enough storage, projects without agreements might suddenly find buyers.

Unfortunately, India’s current battery storage capacity is still painfully short of our needs. But it’s not for a lack of trying. It turns out that we’ve tendered a lot of energy storage projects, but awarded or built only a small fraction so far. In fact, we’ve been rushing to deploy storage fast, rolling out some of the world’s largest battery procurement auctions.

But the tenders have a major problem in how they’re rolled out — they have been eye-poppingly cheap, perhaps too cheap.

And that’s the story we’ll be telling you today: one of lopsided incentives and rosy assumptions guiding a key part of India’s energy strategy.

Lopsided incentives

Recent bids to build grid-scale battery energy storage systems (BESS) have come in at record lows. In Rajasthan, for instance, an auction drew 50+ bidders and delivered a jaw-dropping low price of around ₹1.50 per kWh for storage service. That’s roughly one-third of what industry folks say is a healthy tariff for battery storage — around ₹4–5 per unit. Reportedly, even the Power Ministry was stunned by such bids.

How did prices get so low? A big reason is how the auctions are conducted.

In the eagerness to discover the lowest price, the tenders didn’t enforce strict qualifications. Unlike standard power tenders, early BESS tenders often had minimal technical and experience requirements. This opened the floodgates to a crew of bidders, including those who had little to do with energy, or have probably never even seen a BESS before — like companies in real estate, food processing, construction, etc. With few entry barriers, the competition became a race to the bottom.

Established energy firms (like Adani) didn’t want any part of this madness. Many of them sat out or bid very conservatively, unwilling to chase irrational prices. In their place, less-experienced, or even unserious players put in ultra-aggressive bids to grab a piece of the action.

This lopsided dynamic of incentives is helping nobody. We now have several big BESS projects awarded at tariffs so low that developers will struggle to make any money — if they even build them at all. In fact, a number of recent winners appear to be treating it as a “finance play”, winning the tender with no intent to execute themselves, but hoping to flip the project to someone else at a premium.

If they fail to sell or build, the project just collapses, potentially leaving banks with dud loans, and the grid with little or no storage.

Cheap dreams, fragile foundations

However, the structure of the tenders is only one half of why the bids went so low. The other half is that solar companies themselves are banking on certain assumptions about future costs. And some of these assumptions might be a bit too optimistic.

Essentially, bidders are betting that battery prices will keep dropping sharply year after year, in line with the past decade’s trajectory. One such huge assumption is that today’s glut of Chinese-made lithium batteries will continue to become cheaper. Another is that interest rates will stay low, and so on. Moreover, they also expect that nothing major will upset the supply chain apple cart.

Lots of things need to go right for this future to pan out. If that doesn’t happen, this could all crumble like a house of cards. And there are some signs that not all of these dynamics might pan out as per those assumptions.

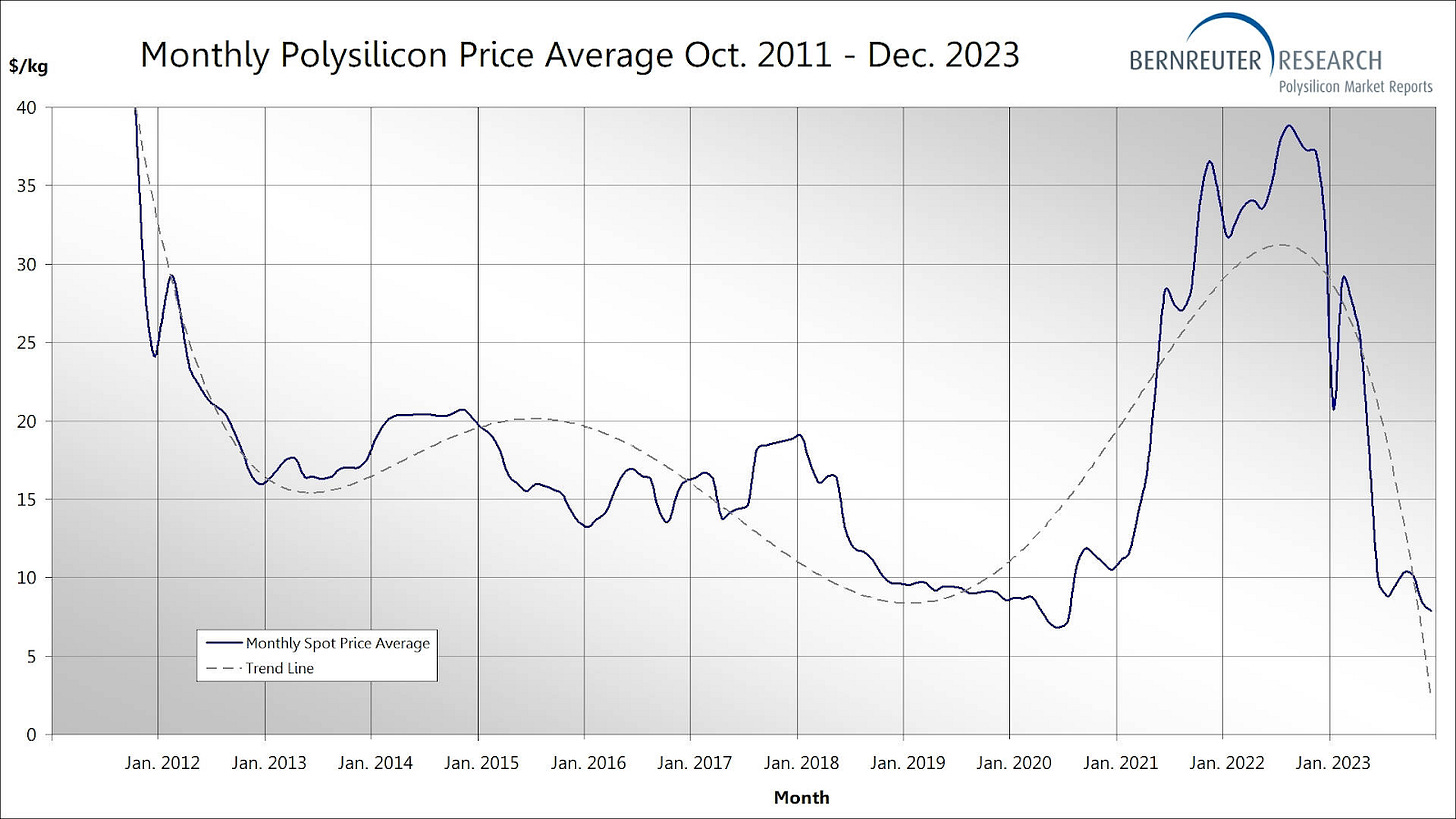

The first sign is the Chinese glut itself. In the recent past, Chinese manufacturers have been flooding the world with dirt-cheap solar and battery gear, selling at rock-bottom prices to clear out oversupply. Developers in India benefited from this fire sale, locking in cheap panels and cells.

But that era is already ending, as Beijing has stepped in to stop this. China is cutting back polysilicon and battery output, and has axed an export VAT rebate that kept prices artificially low. In effect, this should make Chinese solar modules and batteries more expensive.

We’ve seen this story before. A few years back, during a polysilicon crunch – a raw material in solar panels – module prices spiked and Chinese suppliers even walked back on some really cheap contracts that they had signed. Battery materials are no different: lithium carbonate prices rocketed by 6× in 2021-22 and then crashed in 2023.

Many of India’s low BESS bids assume they can source super-cheap cells from China indefinitely. That’s a fragile foundation, especially when 90% of the global supply of certain battery chemistries (like LFP) is controlled by China. Bidders banking on continual cost declines driven by China could be in for a nasty surprise.

There’s another dark side to these cheap bids: the temptation to use subpar equipment and cut corners. Developers might opt for cheaper, lower-grade battery cells that have shorter lifespans, or even downgrade (or remove) safeguards like cooling systems and fire suppression.

At these tariff levels, projects could be forced to rely on “super cheap” cells that aren’t battle-tested for the intense stresses of India’s energy grid. In India, deploying large lithium-ion farms in hot climates is still new territory, and safety standards are still catching up. If players start bargain-hunting beyond the best suppliers, the risks multiply. Unlike low-grade solar panels, a shoddy Battery Management System (BMS) can literally blow up in your face.

Finding our way out

If we don’t get this renewable-plus-storage equation right, the fallout could extend far beyond some failed projects or stranded solar modules. On a broader level, it could halt the progress we have made towards the goal of net-zero emissions.

The hard truth is that coal continues to be ramped up while our storage roll-out falters. Experts are already projecting that, given the current trends, coal will remain the backbone of India’s power supply well into 2030. Without sufficient storage or flexible backup, the grid operators have no choice but to keep coal and gas plants running to handle evening peaks, or even sudden dips in renewable output.

How do we get out of this trap? The good news is that the problems, while hard, are largely fixable.

The first, most obvious fix is redesigning renewable and storage tenders for success, not just lowest price. That means incorporating quality and experience filters so that only serious, capable players participate. Future battery storage bids should require proven technical credentials or partnerships with experienced integrators.

We also need a reality check on pricing — ultra-cheap bids shouldn’t always win by default. One solution floating around for this is to set a reasonable benchmark price for BESS. Bids that are too far below this benchmark will have to undergo extra scrutiny. Basically, if someone bids ₹1.5 when everyone else is at least double that, it’s worth asking how they plan to pull off that magic.

Secondly, we should right-size the auction targets to what the grid and market can absorb. Instead of dropping 4,000 MWh of storage or 5 GW of solar on the market in one go and hoping someone buys it, break procurements into phased, digestible tranches.

On that note, a big fix is to lock in offtakers early. We can’t keep auctioning projects and figuring out buyers later — that clearly isn’t working. Central agencies and states need to coordinate so that every renewable/storage tender has committed buyers upfront, or immediately after auction.

Will this permanently solve the problem of record-low battery storage bids? Well, we aren’t in the business of predicting the future, but it could certainly have immediate material impacts. Moreover, if nothing else, these fixes will certainly make the Indian solar ecosystem more sustainable and reliable.

Tidbits

JioHotstar to invest ₹4,000 crore in South India’s content ecosystem

JioHotstar will pump ₹4,000 crore over five years into South India’s creative industry, unveiling 25 new South titles and partnering with the Tamil Nadu government to build production capacity. The plan includes writer labs, creator training, and job creation—1,000 direct and 15,000 indirect roles—as Jio pushes deeper into regional OTT.

Source: Economic Times

Oracle’s heavy OpenAI dependence triggers investor worry

Oracle’s massive $300 billion OpenAI contract and debt-fuelled datacenter expansion are drawing scrutiny. Its stock has given up all gains from a recent AI-driven surge, while credit default swaps hit record highs. Analysts warn Oracle is overly exposed to one customer even as AI-linked cloud revenues are set to jump 71% this quarter.

Source: Reuters

EU opens antitrust probe into Google’s AI training practices

The EU has launched a probe into whether Google is unfairly using publishers’ and creators’ content to train its AI models. Regulators will also examine if Google’s terms disadvantage rival AI developers. Brussels says innovation can’t come at the cost of competition or creator rights, marking another escalation in its crackdown on Big Tech.

Source: Financial Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Fascinating deep dive into how platfrom economics dont solve content creation risk. The venture capital comparison is spot on, Netflix had to learn the hard way that algorithms cant manufacture hits. What's underappreciated is how Skydance's cloud-based production actually creates differnt advantages than streaming distribution, theyre solving a totally seperate bottleneck in the value chain.

Great article team.

Nitpick: In Roll credits? sections, first statement: "We have no idea.", word idea takes to some insurance site (https://www.nosenzo.it/index.php/it/)...