India’s push to get the aam aadmi to fly

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Inside India’s Regional Aviation Story

Indian IT is getting a shakeup from below

Inside India’s Regional Aviation Story

If you’ve ever glanced at the news and wondered why obscure places like Kalaburagi or Kishangarh or Pakyong suddenly have airports, or why little-known airlines like Fly91 Shankh Air exist, you’re not alone.

These are, however, not accidents. While stock market chatter about airline stocks revolves around IndiGo or air traffic through India’s biggest cities, a whole other story has been unfolding in the background. It’s the story of regional air connectivity.

What’s driving these changes? Why are new airports sprouting in tier-3 towns, and who is flying these routes? To understand that, we need to rewind to a policy launched in 2016 that promised to make the common citizen fly. It’s called “Ude Desh ka Aam Naagrik” — UDAN in short — and that’s what we’ll be diving into.

How It All Started

In 2016, the government unveiled UDAN under the new civil aviation policy that aimed to connect India’s remote areas through affordable flights. As per UDAN, bids would be invited from airlines to operate in new routes identified by the government.

But, to turn this vision into reality, sweetening the deal for both airlines and consumers was necessary. After all, private airlines are profit-driven. They wouldn’t touch an unproven small-town route unless there was something in it for them. Similarly, if people don’t find enough value in travelling through flights compared to buses or trains, there will be no adoption.

So, UDAN’s architects came up with a bundle of incentives.

First, they had to create demand by pushing prices down. Tickets on UDAN flights were capped at about ₹2,500 for a one-hour flight (roughly ~500–600 km). At least half the seats on each flight had to be sold at these subsidized fares, while the other half could be decided at market rates by the flight operator. Sometimes, the same flight would show two different prices on the same day. But the message was clear: consumers shouldn’t have to worry about spending so much of their money on air travel.

But while cheaper tickets could bring demand, they would suppress supply if airlines couldn’t cover their costs. And so, the government responded with a subsidy. Through a dedicated fund, created by levying fees on non-RCS routes, the government agreed to pay airlines the difference for the first 3 years of an UDAN route. Essentially, it is underwriting the risk for an airline to try out a new route.

Besides this, the government was also willing to waive off overhead expenses if airlines took to these routes. Taxes on aviation turbine fuel at UDAN airports were slashed, often to just 1-4% VAT. Airport charges like landing, parking and navigation fees were done away with at some airports.

The scheme also practically guarantees airlines a monopoly on the new routes they took. Under UDAN, once the airline won the bid to operate on a regional route, it earned exclusive rights to that route for three years. No rival airline could start the same route during that window. If that route proved to be popular, the upside would be enormous, and there would be no competition to take any part of those rewards.

Ready for takeoff

These incentives helped UDAN take off.

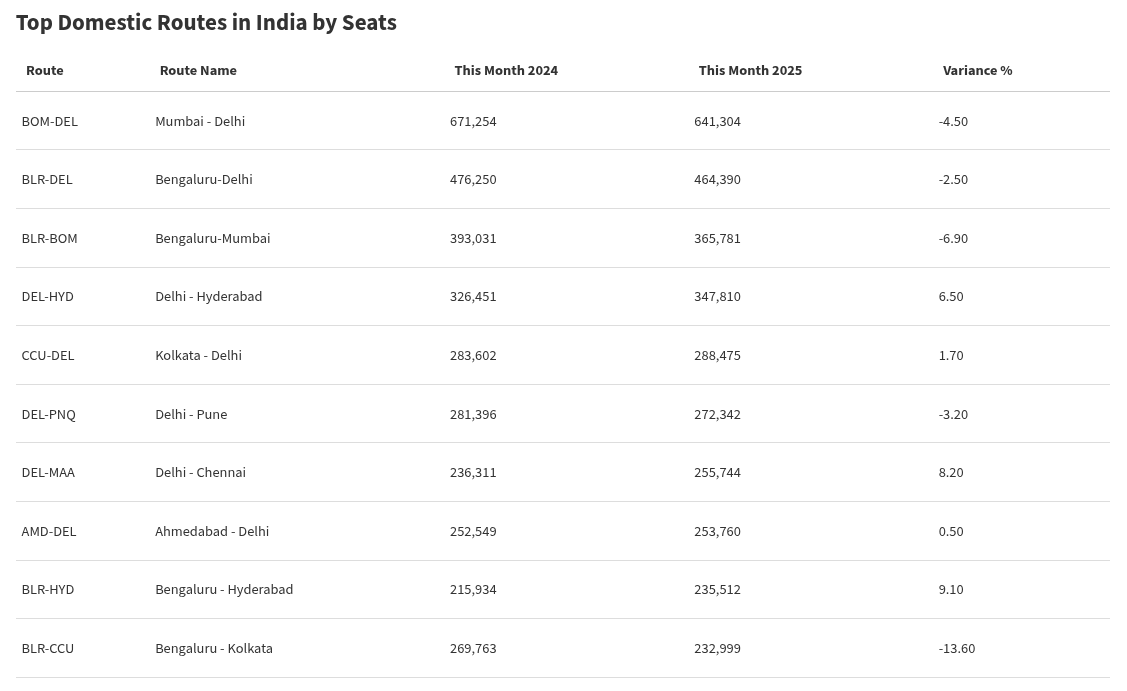

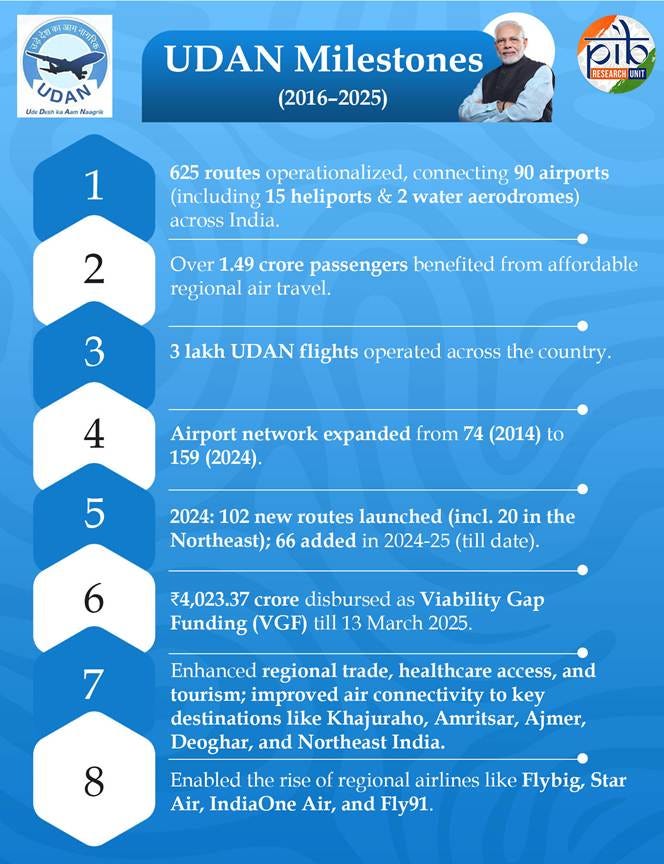

Over multiple bidding rounds, hundreds of routes were awarded to airlines. As of October 2025, UDAN had operationalised over 649 routes, connecting 93 airports (many of them revived from scratch or brand new), plus 15 heliports and 2 water aerodromes. More than 1.5 crore passengers have flown on UDAN flights — many of whom never had an airport in their town before. Thanks in part to UDAN, India’s total airport count more than doubled from 74 in 2014 to 159 by 2024.

Take Kishangarh Airport, near Ajmer in Rajasthan — a prime example of UDAN’s promise.

Kishangarh is famous for its marble industry, but before 2017 the only way in or out was a long drive. UDAN changed that by introducing direct flights from Kishangarh to metros like Delhi, Hyderabad and Mumbai. Local marble traders could literally fly in clients or samples at a day’s notice, and reach big markets faster. A government brief noted that Kishangarh’s marble trade increased partly due to this new air connectivity.

Importantly, UDAN also nurtured a new breed of small airlines.

The policy gave a push to a special category called “Scheduled Commuter Airlines” — basically, niche regional carriers flying small planes (up to 20-40 seats) on thin routes, compared to Scheduled Domestic Airlines with more than 40 seats. Over the past few years, names like Fly91, Shankh Air, Star Air, IndiaOne Air, and Air Taxi emerged to fly in these regional skies.

Cracks in the runway

Now, every new scheme goes through turbulence, and UDAN is no exception. After the initial hype of inaugurating new flights, reality started to bite.

The most recent data paints a sobering picture of how much of UDAN’s promise has struggled to get off the ground — sometimes literally. The Comptroller and Auditor General’s (CAG) report from 2023 and other official replies have been very candid about the gaps.

Up to UDAN’s first 3 rounds, 52% of all awarded routes never even commenced operations. Yes, over half the routes that airlines won in the bidding didn’t see a single flight. And sustaining them was even harder — only 14% routes made it through the full 3-year subsidised period, and a mere 7% of the total were still flying after the subsidies ended.

In short, for every 100 routes touted under UDAN, only 7 turned out to be truly viable long-term. That’s a tiny success rate that raises serious questions about planning and demand forecasting.

Why did that happen? There are a few reasons.

First, airlines simply pulled the plug when flights went empty or losses piled up. In many cases, demand was far below expectations — planes were flying with too many empty seats. The government subsidy wasn’t enough to cover the deficit. Low passenger uptake meant that routes that looked good on paper couldn’t survive in reality.

UDAN’s subsidy funding was designed as a tapering support — after three years, an airline was supposed to stand on its own feet on that route. But those 3 years weren’t enough. As soon as the subsidy stopped, many routes became unviable overnight. Airlines had priced those tickets low due to the fare cap, and once they had to do so without government top-up, the economics failed.

In fact, after an initial spurt, UDAN passenger traffic declined from 33 lakh in FY2022 to about 18 lakh in FY2024 as earlier routes dropped off the map when their subsidies expired.

Second, there was also a huge infrastructure gap that UDAN didn’t really cover.

It turned out that building or reviving an airport is one thing, but making it fully functional is another. A number of UDAN airports lacked basic operational infrastructure. Some had no night-landing facilities or instrument landing systems, meaning flights could only operate in daylight and clear weather.

Others had no refueling stations or maintenance hangars on site, so aircraft had to carry extra fuel or fly out empty to tank up elsewhere. There were instances where airports were technically “open” but didn’t even have proper terminal lighting or perimeter security in place.

SpiceJet, a major UDAN participant, cited cases where they had to suspend routes because the airport was “not ready for operations” – for example, at Thanjavur, Moradabad, or Saharanpur, where scheduled flights couldn’t start since the airport infrastructure wasn’t completed or operational. Such gaps made several routes unviable from day one, as flights got frequently cancelled or delayed due to operational constraints.

Finally, a fundamental structural problem has been the size of aircraft most airlines deployed.

UDAN was meant for small aircraft on thin routes – ideally 10, 20, 30-seaters. But the market reality is that India has very few such small planes in commercial service. Instead, airlines used their ATR-72s (70-seaters) or even Airbus A320s (180-seaters) for UDAN routes. These planes are efficient on thicker routes as they bring overhead costs down, but on low-demand regional legs they are often like half-empty buses. Flying a larger plane with barely a dozen passengers is a surefire recipe to lose money.

There’s another problem. Many smaller airports can technically only handle small propeller planes, yet the airlines who have the capacity to serve them don’t find it economical to buy and deploy such small planes.

IndiGo, for example, ordered hundreds of new Airbus A320neo jets for its main network expansion, but has shown little interest in acquiring 20-seater aircraft for true last-mile connectivity. Their strategy (like that of most large carriers) remains metro-centric, but a metro-centric strategy doesn’t work for regional routes at all. Clearly, UDAN’s value proposition hasn’t convinced the big players to go all in on regional flying.

These cracks show that while UDAN succeeded in kick-starting regional connectivity, it has struggled with keeping it sustainable. Routes have come and gone like a flicker. Airlines that enthusiastically joined the scheme have also burned their hands on these routes. None of this is to say that UDAN did nothing – it clearly did a lot – but it shows the magnitude of the challenge.

A reality check

Eight years, nearly ₹4,300 crore of subsidies spent, and hundreds of routes later, where does UDAN’s progress rank?

The answer is a mixed bag. On one hand, the scheme indisputably scored some firsts. It put Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns on the aviation map. Over 1.5 crore people – many from smaller cities – experienced air travel, often as first-time flyers. UDAN also spurred investment in airport infrastructure across states – from new terminals in the Northeast to upgraded airstrips in Uttar Pradesh.

However, after all this time and money, the scale of regional aviation is still just a drop in the bucket of India’s overall air travel. That’s roughly 1.4%. In other words, for 98 out of 100 Indian air travelers, UDAN might as well not exist.

And why is that? Possibly because real demand on many of these thin routes is just not there – at least not at fares that make commercial sense. Indeed, India’s shiny new Vande Bharat Express trains have become a worthy competitor to UDAN flights.

To be fair, it was unjust to expect UDAN to totally revamp the Indian aviation sector since metros would continue to remain demand centres for this service. Whatever little it did to spurt regional connectivity is visible, but was it enough? More importantly, is there more that should be done or this is just how regional air travel will always be? These are difficult questions we too are finding answers to.

Indian IT is getting a shakeup from below

A few days ago, we examined the latest quarterly results of India’s large-cap IT giants, like TCS, Infosys, and HCLTech. Of late, their story has been one of flattening growth, falling margins, and a slowness to adapt. And while their Q2 FY26 results were decent, they’re hardly indicative of a comeback.

But if you only focused on these huge companies, you’d be missing the forest for the trees. Zoom out slightly, and you’ll see that these firms are being shaken up from below by their own, smaller peers.

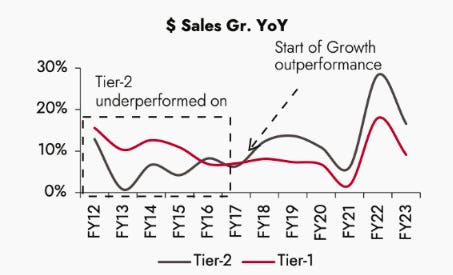

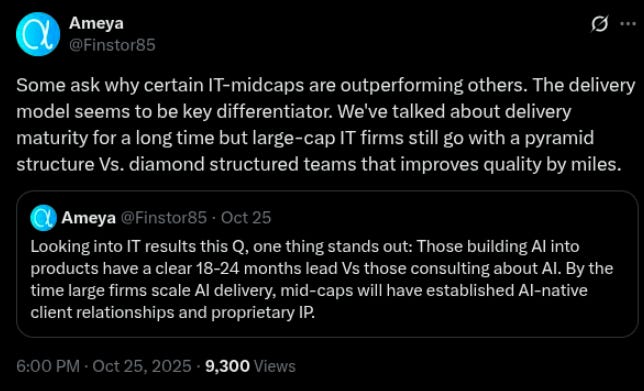

What’s even more interesting is that a decade ago, the story was completely different: large-cap IT firms were beating midcap firms handily. But in 2017, something switched, and since then, smaller firms have been outperforming larger ones.

But this isn’t really by accident. They reflect a business model that’s a bit different from what their bigger peers do — even, at times, eating into the lunch of tier-1 IT firms.

So, let’s dive into the results of three such companies — Persistent Systems, Coforge, and Tata Elxsi — to see what’s really going on in India’s mid-sized IT firms.

Two different worlds

To understand why midcap IT is thriving, you need to first understand how the dominant business model in IT works.

The Large-Cap Model: Scale and Stability

India’s IT giants were built on a simple premise: Western companies need armies of engineers to maintain their IT infrastructure, and India can provide that talent at a fraction of the cost. TCS, Infosys, and Wipro became masters of this trade. When a bank buys a core banking software, these firms help integrate it, customize it for local needs, run it day-to-day, and fix it when it breaks. It’s steady, recurring work.

This model is manpower-heavy. Success is measured by how well these companies utilize their existing staff.

A lot of their revenue comes from what they call vendor consolidation and cost-takeout deals. What does this mean? Well, say you’re a bank that needs to cut costs. You’ve figured that your IT systems are one place where that can be done: you have way too many vendors for different kinds of software. So, to streamline this, you’ll hire a TCS or Infosys, who will consolidate these services and cut your IT costs.

Engineering Over Operations

Midcap IT firms, however, took a slightly different path. Companies like Persistent Systems and Coforge positioned themselves not as body-shops like these larger firms, but as specialized engineering partners. They don’t merely maintain software, but they build it. And unlike larger firms which tend to be more broad-based in domain knowledge, midcap firms are experts in specific domains.

Take Persistent, for instance. The company works directly with Independent Software Vendors (ISVs) and hyperscalers like AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. When a SaaS company needs to add a new feature to its product, or when a cloud provider needs to optimize its infrastructure stack, they typically call Persistent.

Or take Coforge, which is one of the few firms that specializes in travel, building airline systems, designing booking platforms, and so on. They’ve helped build much of the core software that keeps global travel infrastructure running. Meanwhile, Tata Elxsi knows the A to Z of how to install software in cars.

It’s not like large-cap companies don’t do such engineering work, or midcap companies don’t do any managed IT services. But compared to midcap companies, product engineering and R&D makes up a very small part of large-cap revenue, while the opposite is true for many midcap firms.

In today’s age, large-cap companies express fears that the body-shopping model may come to an end soon. At the same time, the operational model of midcap firms is gaining far more importance.

Industry-beating growth

The proof, as always, is in the quarterly results. And in an industry where the large firms are barely hanging in, midcap firms have recorded rip-roaring growth.

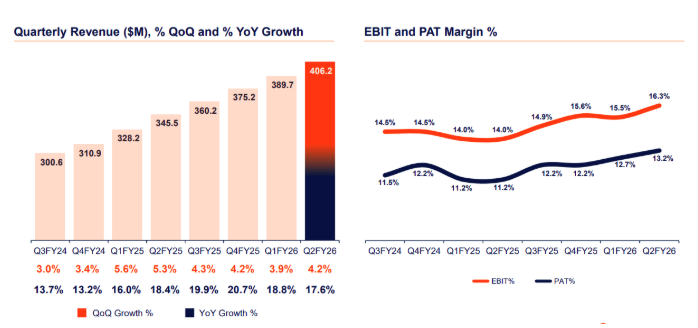

Let’s start with Persistent. They posted ~₹3,605 crore in revenue for Q2 FY26, up 17.6% year-on-year and ~4% from last quarter. Their profit-after-tax (PAT) margin was 13.2% — a whopping ~45% increase from last year. This quarter marked Persistent’s 22nd consecutive quarter of sequential growth.

Then comes Coforge, which had an even better quarter. The company reported ~₹3,986 crore in revenue for Q2 FY26, a 32% increase from the same time last year. Their PAT for the quarter was at ~₹376 crore, which is nearly 10% of the revenue. But what is worth highlighting is that compared to last year, their PAT is close to being doubled. The major segments they play in: banking / financial services / insurance (BFSI) and travel, have all enjoyed solid growth.

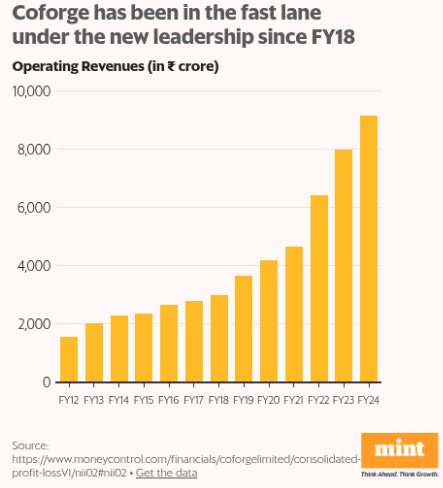

Coforge’s performance is actually far more impressive when you dig into their history. A decade ago, Coforge — then NIIT Technologies — was considered a laggard. Until 2017, it grew 11% every year. But that year, NIIT’s leadership team changed almost overnight, and 3 years after that, it renamed itself. Since then, Coforge nearly doubled their annual growth rate.

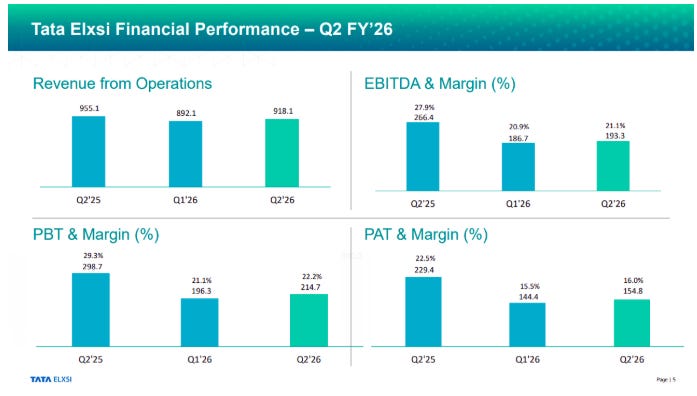

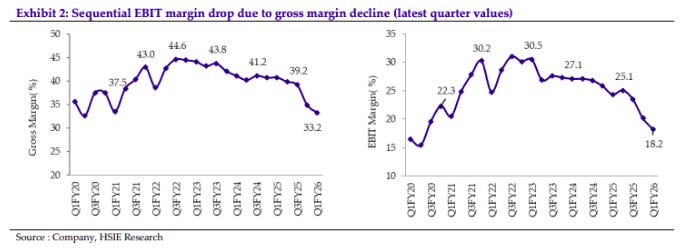

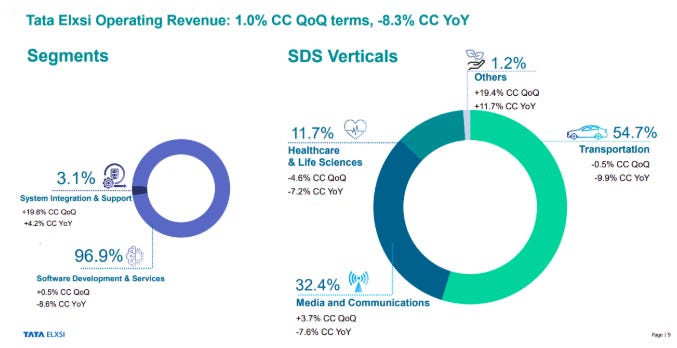

Tata Elxsi had a more sobering second quarter. Revenue grew by ~3% this quarter to ₹918 crores, but it is actually ~4% down from what it was last year. The operating margin this quarter is 21%, while the PAT margin is at 16%.

However, it’s worth seeing how Elxsi has performed over time. Since FY21, Tata Elxsi has doubled its annual revenue to ₹3,729 crore. In fact, before this year, their operating margins were extremely high, almost touching ~30% in FY24. For context, at the same time, Infosys recorded only ~24% operating margins.

So, why have the margins fallen so much? Well, the answer boils down to the industry they specialize in. Lately, global automakers have been cutting back on their investments and R&D spending. This partly reflects economic uncertainty due to tariffs, and partly declining profits due to a global price war.

Additionally, a major client of theirs was hurt by a massive cybersecurity attack, which hurt their growth this quarter. Now, they didn’t explicitly say who the client is. But, Jaguar Land Rover — well-known to be one of Elxsi’s biggest clients — did suffer such an attack this year, nearly halting their production.

The secret sauce

So, what’s behind these standout results? Let’s take a look at the structural advantages some of these businesses possess that give them a leg up.

First, domain expertise leads to better deals.

Specialization is a huge moat for midcap IT, especially as clients are increasingly getting frustrated with large-cap IT’s “one-size-fits-all“ approach. Midcaps offer lean teams with more experienced specialists (than junior-level employees) that work directly with the client’s engineers. In contrast to the pyramidical structures of larger companies, this diamond model of delivery of midcap firms makes a big difference.

Take Tata Elxsi. Their peak EBIT margins were no accident—they reflected premium pricing for specialized work in auto. The rise of EVs, which have far more electronic content than traditional cars, turbocharged Elxsi’s recent growth. Tata Elxsi also specializes in Media & Telecom work, which makes up over 30% of its business.

Persistent, meanwhile, has cultivated a reputation as the partner of choice for software companies that need to build or modernize their products. This isn’t work you can easily replace with junior resources—it requires senior architects who understand the client’s technology stack intimately.

Coforge’s deep expertise in travel paid similar dividends. It understands airline economics, cargo operations, and the intricacies of global distribution systems. This knowledge helped Coforge win its largest deal ever with Sabre, a global giant in travel technology.

And this expertise is translating to bigger deals — even winning business against their larger peers. Coforge’s Sabre win is the marquee example of this:

Here’s Persistent talking about a banking client, having first stolen them away from a tier-1 peer years ago:

Secondly, the nature of their work puts them close to AI.

By virtue of what they do, some midcap IT firms are much better positioned to capitalize on AI than their large-cap peers.

Persistent, for instance, works heavily with hyperscalers like AWS, who are building AI data centers at breakneck speed. That makes them extremely close to the action in AI and ML.

And they’re making full use of this advantage. Persistent is iterating on its own proprietary AI products, the primary one being called SASVA. It’s a GenAI-powered suite that helps automate large chunks of software development. This quarter, under SASVA, Persistent filed 20 patents, taking the total to 75. Here’s one way SASVA is being used:

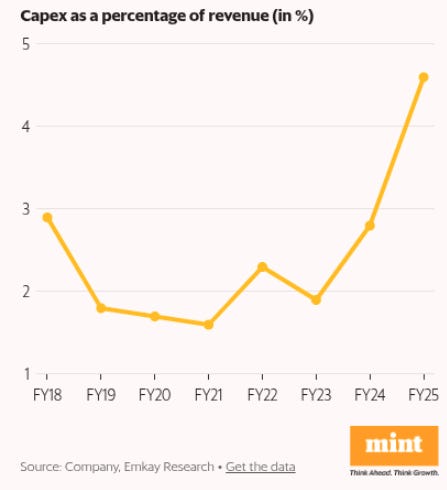

Coforge is also playing the AI game in its own way. In an industry that is known to be asset-light that spends barely 2-3% of their revenues on capex, Coforge has doubled their capex share. And much of it is being devoted to building their own AI platforms and IPs.

Here’s one example from Coforge’s last quarter of how GenAI is being used in a deal:

Other unique strengths

There are other firm-specific strengths that we think are worth highlighting.

Tata Elxsi, for instance, benefits a lot from being in the Tata ecosystem. Tata Motors, Tata Communications and Jaguar Land Rover are some of its biggest clients. While we can’t put a number to it, it’s worth considering that this will be a significant chunk of their business.

Coforge, on the other hand, has benefited from a string of good acquisitions in recent times. Their acquisition of SLK Global, for instance, has boosted their BFSI portfolio. They also acquired Cigniti recently, and the synergy looks to be already contributing to business.

The risks lurking beneath

You may be wondering: if midcap companies are so good, why aren’t they bigger businesses yet? Well, for all their strengths, midcap IT firms do face vulnerabilities that large-caps have successfully avoided.

To begin with, domain specialization is a double-edged sword.

Tata Elxsi’s current struggles highlight the risk of deep vertical focus. The auto business, which is already cyclical, is going through a crisis. Elxsi also highlights how volatile the media & telecom industry is currently.

Persistent faces similar risks too, albeit less acute. Its revenue is heavily tied to ISVs and tech companies. So if a recession hits, the software industry will cut back strongly on new projects and R&D spend, hence requiring Persistent’s services less. Persistent understands this, and has been trying to diversify into projects that don’t depend heavily on such discretionary spend. But they’re far away from fire-proofing their business.

On the other hand, large-caps, with dozens of verticals and thousands of clients, have built-in diversification. They win multi-year, multi-billion dollar deals across many sectors. More importantly, when a recession happens and a client feels like they’ll need to cut IT costs, they’ll reach out to tier-1 firms that know how to do this best. This ensures that they are shock-resistant even in the worst of times.

Secondly, there’s concentration risk.

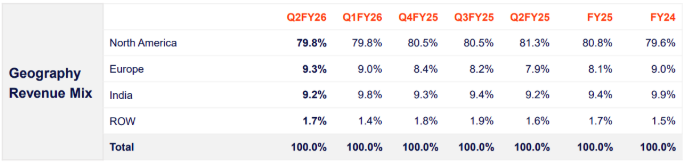

Persistent derives 79% of its revenue from North America, owing to most of the best tech firms being located there. Large-caps, by contrast, have far more diversified geographic exposure—TCS earns nearly 50% from North America.

This concentration means a company like Persistent is highly exposed to US economic cycles, regulatory changes (like H-1B visa restrictions), and client-specific risks.

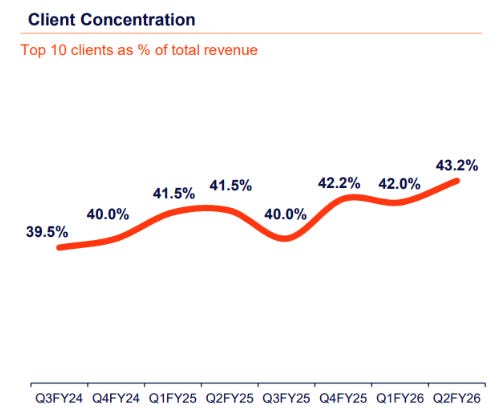

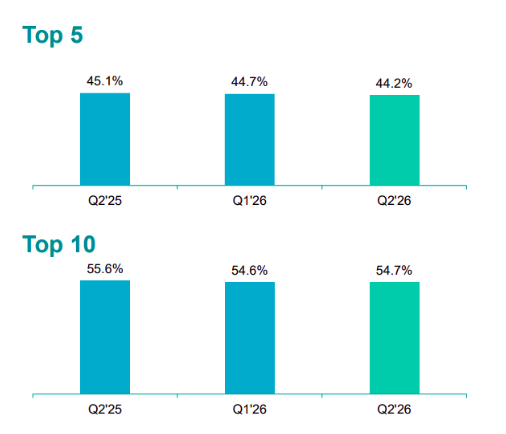

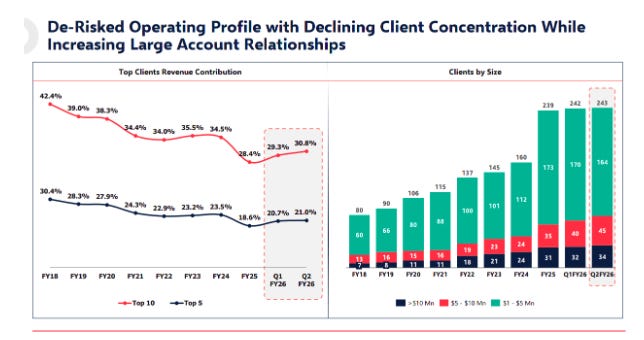

The client concentration is even starker. Persistent’s top 10 clients account for over 40% of revenue — meaning that losing even one major account is a significant blow. For Tata Elxsi, that ratio is a whopping ~55%.

In the case of tier-1 firms, though, the top 10 clients make up just ~20% of their revenue. They wouldn’t hurt as much if they lost one of these clients. In fact, Coforge has been actively trying to reduce their top 10 client concentration.

The bottomline

It’s well-understood by everyone that today, Indian IT is at an inflection point.

Now, that has led to lots of reactions — like predicting the death of the whole industry, or the killing of the body-shopping business model alone. And if it’s the latter, then the path forward is still a little unclear. However, the outsized performance of our midcap firms might offer a way. Companies that are actually involved in how software gets built in their specific domains are having a moment.

By no means is it an easy business to be in. But it is high-value work. And it might play a huge role in deciding what the landscape of Indian IT will look like in a few years’ time.

Tidbits

India will impose a 30% import duty on yellow peas starting November 1, 2025, reversing its earlier duty-free window that was to last until March 2026.

Source: Reuters

Boat’s parent, Imagine Marketing Ltd, has cut its IPO size to ₹1,500 crore from ₹2,000 crore, with ₹500 crore as fresh issue and ₹1,000 crore via OFS by investors and founders.

Source: ET

DP World has pledged an additional $5 billion investment in India to expand its ports, terminals, and logistics network, on top of the $3 billion it has already invested.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The first story was really fantastic. I just read about UDAN 3-4 days back in the book Viksit Bharat 2047 by Aditya Pittie. Indian Govt is on the right track, but you did address all the doubts which I had!

Excellent read on the midcap IT firms. Thank you.