India's huge bet on smart electricity meters

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s huge bet on smart meters

How corporate India survived COVID

India’s huge bet on smart meters

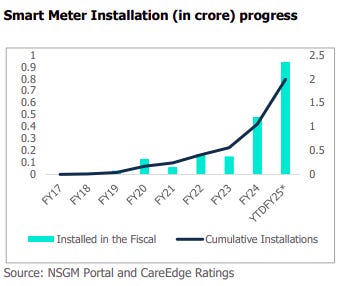

Recently, CRISIL released a sobering assessment of India’s ambitions in installing smart meters to measure electricity. Our plan was to install 25 crore smart meters across all kinds of establishments except agriculture — households, factories, shops, wherever there’s a connection — by March 2026. We’ve barely crossed 10% of that target.

That said, it’s not all bad news. It’s hard to deny that this project of installing smart meters has picked up pace, even if not as fast as we had hoped. It’s recorded solid growth so far in FY25, and as per CRISIL, the revenue of smart meter manufacturers will rise by ~20% this year.

But why even talk about the humble electricity meter? Well, while nobody thinks much about them — us included — they’re a key part of our energy sector. So important, in fact, that considerable government resources are being plowed into just replacing old meters with smart ones. How India’s going about this also reveals how we manage risks in India’s energy sector as a whole, and the innovations we’ve made to minimize those risks. The deeper we went into this story, the more we were blown away by the sheer scale of it all.

So, well, let’s dive in.

The problem with analog

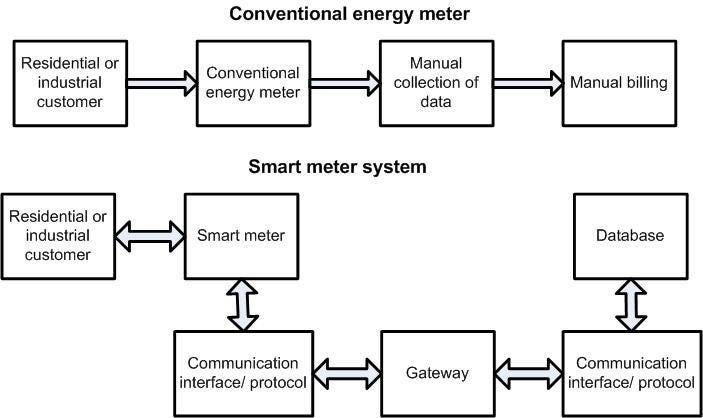

Traditional analog meters are simple counters. They only measure how many units you consumed. An official needs to physically visit your home and actually read the count. That already makes electricity delivery a cumbersome process for our government. But the issues run deeper still.

For one, you can only be charged for power once you consume it, once this count is taken. If a consumer declines to pay at this point, stacking up unpaid bills, there might be commercial losses for power distribution companies.

Additionally, analog meters cannot measure efficiency losses in power transmission. There’s a chance that power can leak out before it reaches the meter. Now, some loss is just part of transmitting power through a wire. But right now, we can’t track where these losses are happening. Apart from making grid maintenance harder, this also makes electricity theft — which is huge in India — trivially easy. One can bypass the meter and hook up an illegal connection without being detected for a long time.

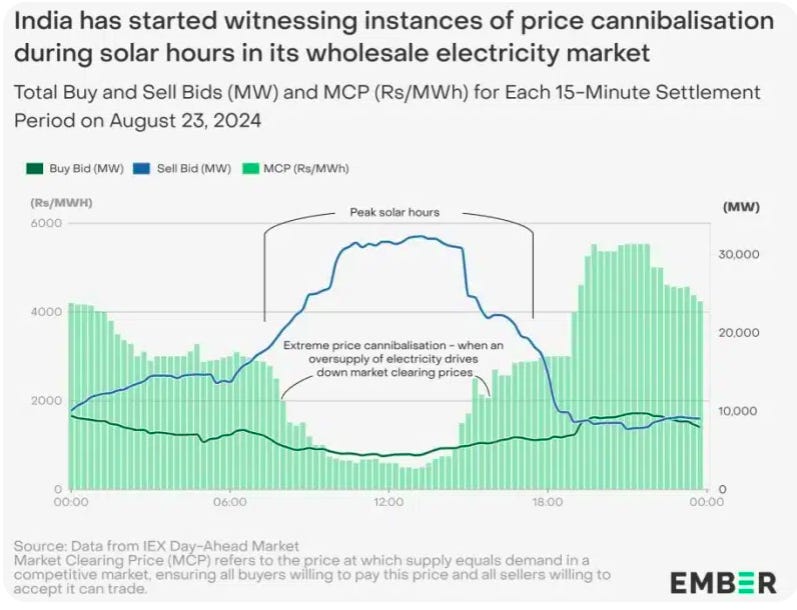

Finally, analog meters only work when you’re giving electricity at a fixed price. They cannot price electricity as per demand and supply. Ideally, a supplier would want to price power according to how much they need to supply, and how much they can procure. For instance, there could be an excess supply of solar power in the day, driving costs down, while peak demand is reached in the evening, after that supply dries up. By reflecting this in the price, they could nudge people to move their power usage to when it’s cheap. But currently, the price is set uniformly for each unit — wasting that clean energy, while forcing us to burn fossil fuel during peak hours.

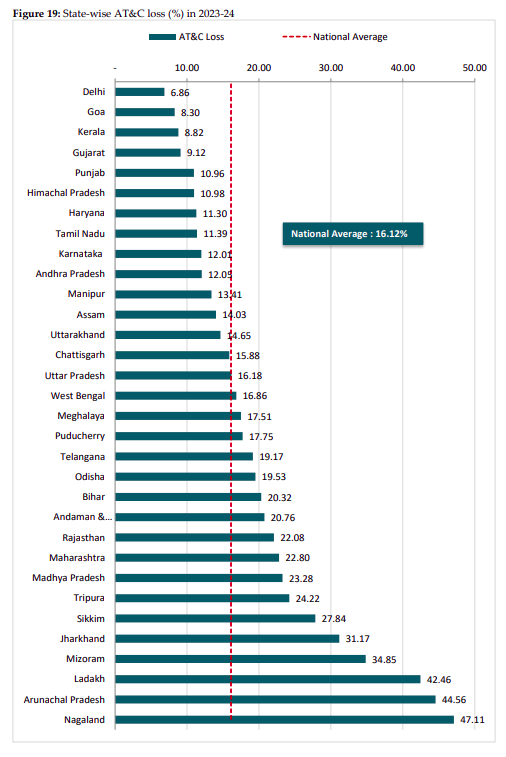

This makes our power sector losses massive. Its aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) losses across India averaged ~16% in 2023-24. That is, for every ₹100 worth of power transmitted, ₹16 vanishes into thin air. In some states, those losses cross the 30% mark. That is crores in lost revenue.

The smart alternative

Enter the smart meter. These are cellular-enabled IoT devices, which measure your electricity consumption, and transmit that data back to the utility every 15 minutes to one hour.

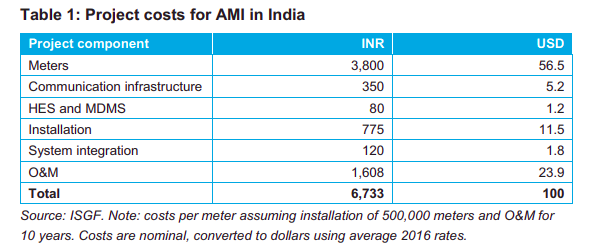

Naturally, this complexity makes them a lot more expensive than analog meters. A single meter can cost over ₹6,700.

Installing these meters isn’t easy either. Teams must coordinate door-to-door visits across millions of households. And moreover, setting them up is more complex than a simple device swap. Each meter needs a SIM card or radio module. At the backend, these must be integrated into billing systems, outage management, and data analytics platforms. And more complex technologies also require better maintenance.

This makes installing smart meters a capital-intensive business.

The benefits, however, are transformative. Smart meters allow automated billing, which eliminates human error and misreading. Tamper alarms instantly flag theft attempts. It becomes possible to price electricity dynamically, based on supply and demand. This also enables prepaid payment — like mobile data, consumers can pay for power before use, with the meter examining how much they use.

For discoms, this permits real-time monitoring of where power goes, makes payments quicker, improves revenue and optimises costs. For consumers, it means transparent bills, and lets them optimise their power use for lull periods. We know that the tech works: in Japan, for instance, every household has a smart meter. In the US, the ratio is 73%.

But we have a long way to go. As of April 2025, a dismal 5-6% of Indian households have smart meters.

The difficulties of putting up smart meters

India had tried to install smart meters at scale before this. Only, we relied on our state-owned discoms to do this. That was a poor choice.

Most state discoms generally operate at a loss, and must be propped up by government bailouts. They can’t afford the huge capex that smart meters demand without taking on further debt. This financial distress also pushes them to delay payments to vendors for months, making private smart meter vendors hesitant to sell to discoms on credit — forcing them to pay for everything upfront.

Discoms also struggled with the technical difficulties of pulling such a project off. They’ve struggled to integrate their smart meters into their outdated IT systems.

It hasn’t been easy for private players to get approval for their products, either. Each model requires a specific certification from the Bureau of Indian Standards (or BIS). However, neither did India have clear standards for smart meters, nor did it have enough testing capacity in labs to ensure products were approved quickly, causing serious delays.

A new paradigm

By 2021, it was clear that this strategy of relying on discoms wasn’t working. smart penetration in India was less than 1%. A new approach was needed. So, in July 2021, the government launched the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS), with a ₹3 lakh crore budget — half of which was dedicated to smart meters.

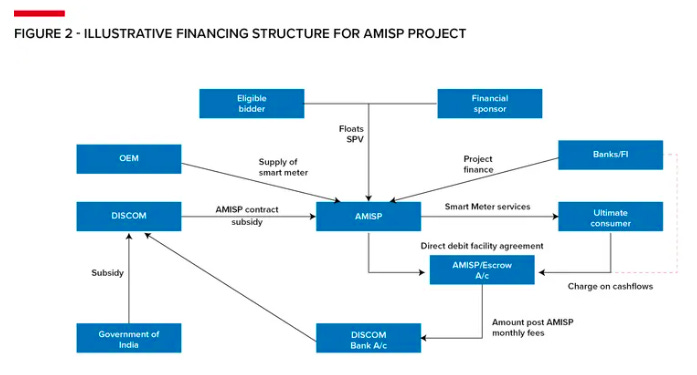

The goal was 25 crore installations by March 2026, and the government debuted a new strategy to this end. It introduced a new framework for public-private partnerships, called TOTEX (or total expenditure). Instead of discoms procuring meters upfront and managing operations separately, the entire responsibility was moved to private sector entities called “Advanced Metering Infrastructure Service Providers” (or AMISPs) for 8-10 years.

Through competitive bidding, AMISPs would be given concessions for a discom area. There, they would finance meter procurement, handle installation for all consumers, establish communication and IT systems, and maintain the whole set up.

For these services, Discoms pay the AMISP a Per-Meter-Per-Month (PMPM) service fee, to cover both the capex efforts and ongoing operations of the AMISP. Crucially, this payment is performance-based — the AMISP only receives full fees if meters increase power efficiency.

Through this program, the RDSS tried dampening the risk posed to discoms, outsourcing operations, and spreading costs across a longer period of time. The operational challenges and risks were made the burden of the private sector, in return for incentives to bear it.

A masterclass in shifting risk

Previously, manufacturers sold meters and booked revenue immediately. Under the AMISP model, though, they must invest upfront and recover money over 8-10 years from utilities with shaky credit. This was extremely unusual for manufacturers, instead resembling the risks you would see in road or infrastructure projects. Would they be willing to buy in?

To manage this risk, companies came up with an ingenious solution to this problem: using Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) to finance projects.

Here’s how it works: a manufacturer partners with an infrastructure investor to create a separate legal entity (or an SPV) that is specific to a project. This SPV bids for the AMISP contract, buys meters from the manufacturer, handles installation and operations, and receives payments from the discom over time.

This is an exercise in compartmentalizing risk. If a particular state project fails for some reason, the financial damage is largely contained within that SPV. A bank that has lent to the SPV can claim its assets as collateral, but the parent company’s balance sheet — while somewhat damaged — still remains protected. On the other hand, the manufacturer only bears the risk of making the meters, not installing and servicing them.

It’s not perfect ring-fencing, but by providing some degree of insulation, it has become the industry standard.

Let’s illustrate this with a real-life example — the biggest AMISP in India, in fact.

Genus Power, India’s market leader in making smart meters, has an SPV with Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, GIC. GIC committed $2 billion to a joint platform for AMISP projects for a 74% stake in the platform. Genus has the rest. GIC also took ~15% equity in Genus itself.

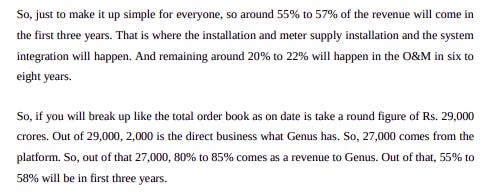

This SPV places bids with the government for contracts. Genus supplies meters exclusively to these SPVs, booking those manufacturing orders immediately. The SPV does all the installation and servicing, funded primarily by GIC’s capital.

Genus’ contract with GIC ensures they get their revenue as quickly as possible. Over half their revenue is expected to come in the next 3 years, while the rest will take another 6-8 years.

This structure offers predictable cashflows to Genus and its investor GIC, while also isolating most of the risks of project failure to just one entity.

Execution, the biggest bottleneck

How has RDSS done so far?

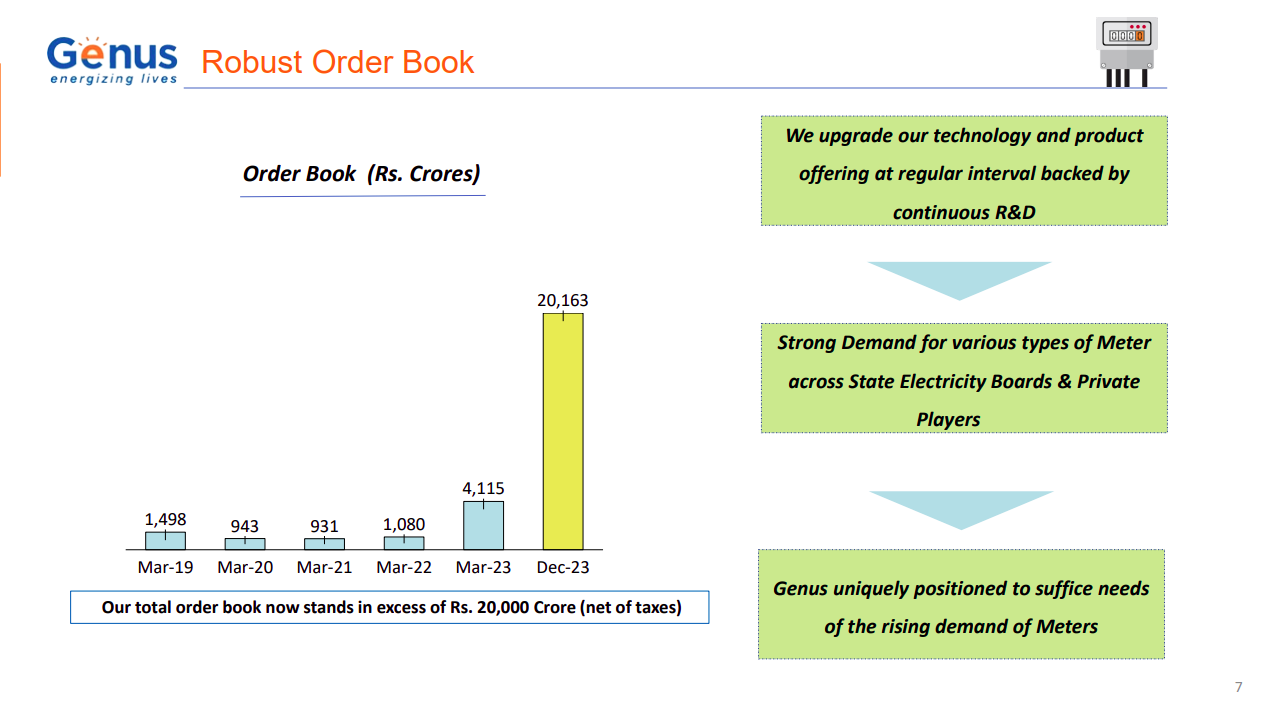

Well, it has made real progress. As of April this year, 80,000 smart meters were being installed every single day — a nearly 8x increase from 12 months before that. The order books of market leaders like Genus and HPL Electric have exploded.

However, the project is still far behind targets. By mid-2025, a total of ~2.5 crore smart meters had been installed, which is only ~10% of the target. That said, contracts for ~12 crore meters have already been awarded — meaning that the large order books of companies are yet to be executed.

These delays also point to the difficulties in execution that still exist.

The most critical one is the payment risk from discoms. The RDSS had envisioned faster payments, but many discoms still follow the old, long payment cycles, creating 90-180 day receivable periods for AMISPs in some cases. CRISIL warns that such persistent 6-month payment lags could erode the viability of projects.

It’s also hard to get approval to replace meters or install new networks for them, especially in dense urban areas. Various states have challenged the Central government over the compulsory requirement of installing smart meters. In fact, smart meters are now a politically sensitive issue.

Then there are infrastructure delays. For instance, in areas with poor telecom coverage, smart meters won’t be able to transmit data back to the server. The existing, outdated IT infrastructure of discoms, too, make execution difficult.

Lastly, there’s consumer resistance. The shift from postpaid to prepaid has not been easy for consumers. Consumers often assume that smart meters overcharge, invade privacy, or will even disconnect power harshly. Some households refuse installations on the grounds that meters are being installed against their will. This requires more consumer awareness that can only happen gradually.

A truly smart power grid

This is a story that will only grow more important with time — especially as we furiously add to our renewable energy capacity. But it’s also a story about how we create systems to adapt to new risks.

Though late, the recent growth in smart meter installations has been impressive. As installations accelerate and more data comes online, they could create a positive feedback loop: better discom finances, which enable more investment, which improve service quality and consumer trust, which makes reforms politically easier. The early signs of such a loop are there.

For something we rarely notice, smart meters can really shift the needle on how India manages its energy ambitions.

How corporate India survived COVID

It’s easy to forget this, today, but when the COVID-19 pandemic first broke out, it hit India’s economy like a heart attack.

Amidst a country-wide lockdown and world-wide chaos, the first quarter of FY 2021 saw nearly a quarter of our economic activity — 23.8% — wiped away, compared to the previous year. The prognosis for corporate India was grim. Sales plummeted. Manufacturing and non-IT services sales fell by 41%. Any business that didn’t live online faced an existential crisis.

Back then, it was easy to imagine that Indian companies could see a prolonged period of distress even if the pandemic faded away, simply because of how bad this single shock was. From our current vantage point, though, it seems like our worst fears didn’t come to pass.

How did we make it through? A new RBI paper examines this phenomenon. It analyses detailed financial data from over 3,000 listed companies to try and piece together what happened. And through that, it argues that corporate India didn’t just survive the pandemic, but emerged from it stronger.

The emergency room

While it lasted, the COVID-inflicted contraction in our economy was perhaps the sharpest peace-time economic shock we had seen. It had become impossible to do most sorts of business. If you ran a factory, or a hotel, or a construction company, or a transport business — or really, anything that required you to be in the physical world — your revenues disappeared.

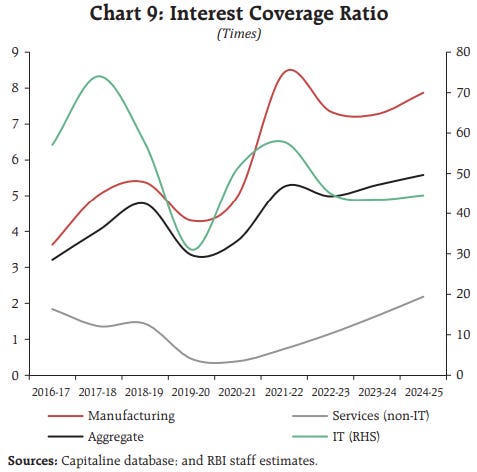

While this was a crisis for the best of companies, things could have gone seriously wrong if you had taken debt. Economists use something called the “interest coverage ratio” (or ICR) to understand if a company can pay its debt back. If you have an ICR below 1, the interest you owe is more than your operating profit — and you’re at severe risk of a default.

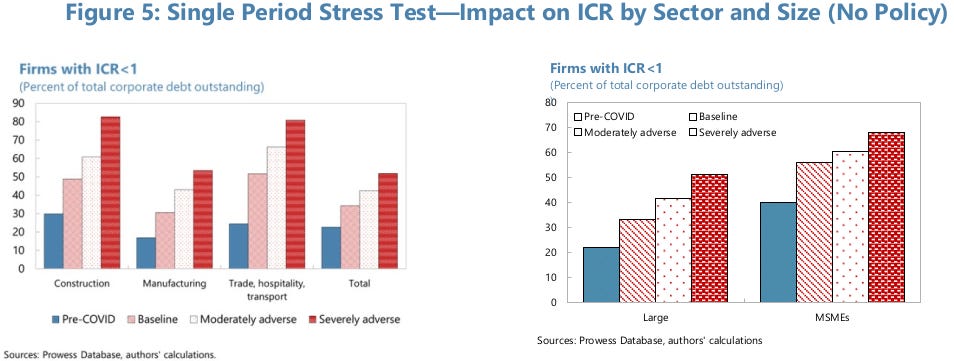

In November 2021, the IMF studied India’s economy to understand just how bad things looked. Looking at over 20,000 firms, it found that before the pandemic began, over a quarter of Indian firms were already struggling with their debt loads, with an ICR under 1. But COVID could have made things much, much worse. In its baseline, over 36% of Indian firms would be at risk. In a worst case scenario, over half of India’s firms would have found themselves in distress.

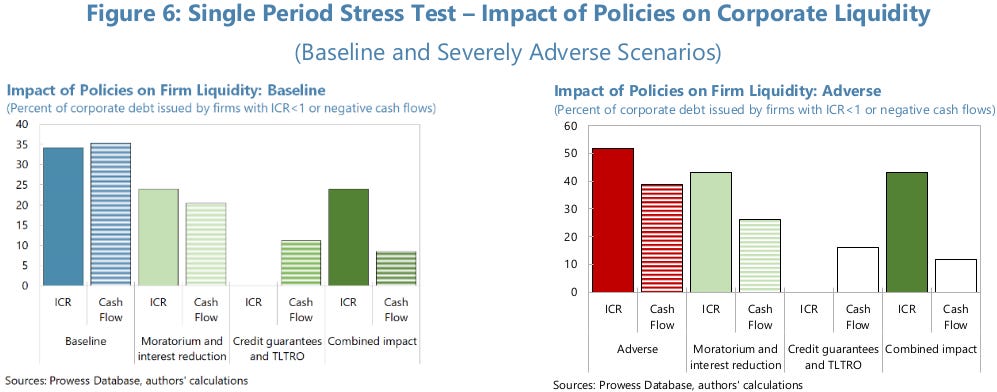

The reason they didn’t was that the RBI rushed to their rescue.

RBI pushed out over a hundred emergency measures in those days. This ranged from the conventional — like a repo rate cut by 250 basis points — to the extraordinary. For instance, it announced a six-month loan moratorium, gave out credit guarantees to MSMEs, carried out long-term repo operations, and more. This kept many firms on the ventilator, even as cash flows had halted.

Despite all these measures, though, corporate India was fragile.

The RBI’s measures were meant to keep corporate India liquid, but not solvent. They ensured that companies wouldn’t collapse for lack of cash. But eventually, they would still have to adapt to this new situation, and deal with their debts. The RBI had wagered that Indian companies weren’t fundamentally broken — they were healthy businesses, which had lost their ability to generate cash. Given enough time, they would recover once the economy re-opened.

As the RBI’s paper argues, corporate India proved the RBI right.

The recovery

The RBI, in its paper, studies more than 3,000 non-government, non-financial (NGNF) firms. It looks at how they were doing before the pandemic, how the pandemic affected them, and how their performance changed once the pandemic abated.

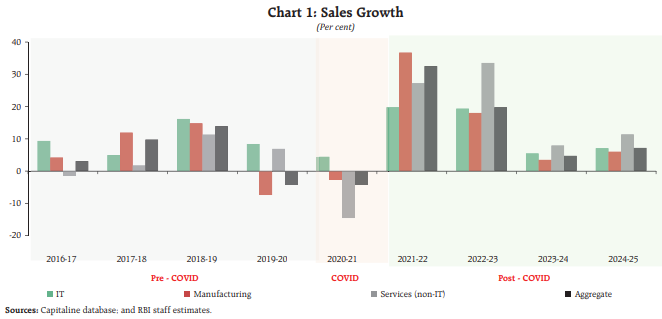

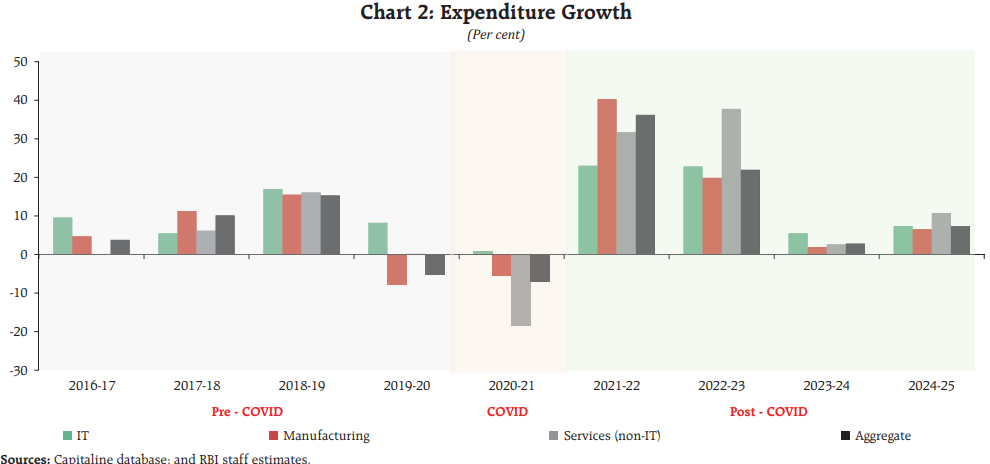

In the years before the pandemic, corporate sales growth had been shaky — but had been picking up momentum. From an unspectacular 3.1% in FY 2017, it had grown to a robust 14% in FY 2019, but FY 2020 had seen another contraction. And then, in FY 2021, sales went into a free fall. This is what forced the RBI to jump in.

At this point, things could have gone either way. There was no guarantee that revenues would return.

But they did, dramatically. In FY 2022, sales saw a strong rebound — shooting up by 32.5% year-on-year. This was, of course, on the back of a terrible year. Some recovery was to be expected. But it also pointed to genuine economic dynamism. FY 2023 was yet another strong year, with sales growing at 19.8%. By FY 2025, they had moderated to 7.2%. By this point, our economy had convincingly seen itself through what could have been a horrible crisis. And hearteningly, much of this recovery was broad-based — cutting across sectors.

This is something that you probably already know. What’s more curious, however, is how this turnaround was achieved. Because, as the RBI finds, the corporate India that had emerged from the pandemic wasn’t what it was in the years before. The crisis had changed Indian business. In a few short years, companies had re-wired their business models at breakneck speed. They had reconfigured their supply chains, and changed their cost structures.

An open-heart surgery

Surviving the pandemic

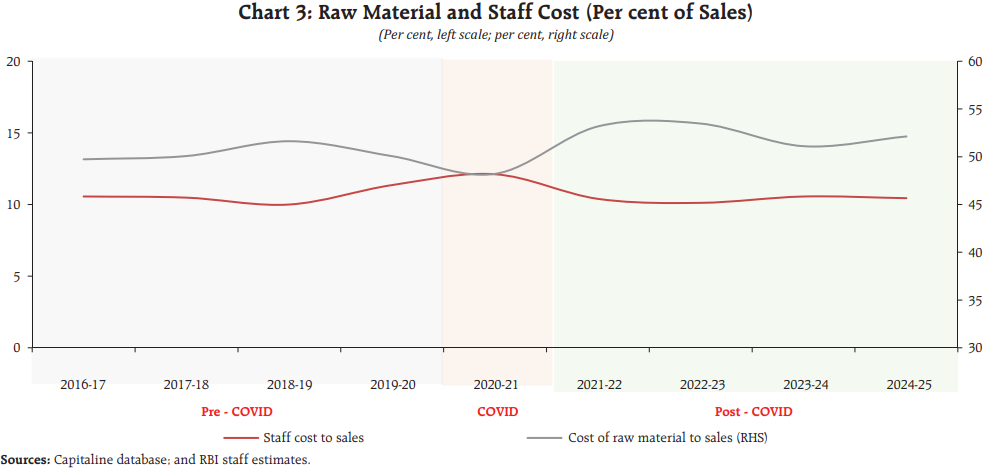

For a while, during the pandemic, companies’ biggest challenge was simply to make it through to the other end. As revenues collapsed, firms were forced to slash expenses to the bone. Global commodity markets, thankfully, had fallen all around, giving them room to slash their spending on raw material. Companies also held off spending on their personnel — with staff costs growing at just 0.3%, compared to 8.1% the previous year.

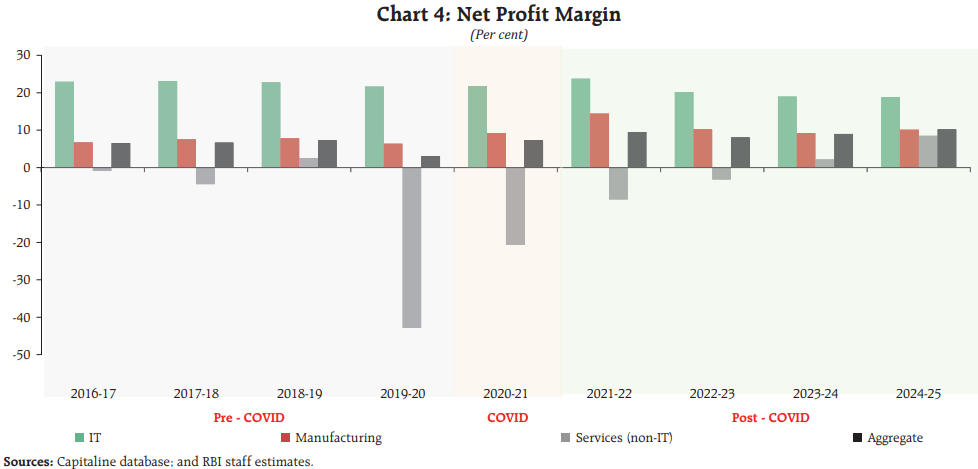

As a result, while their sales had taken a hit, companies succeeded in cutting their expenses even deeper, allowing them to keep afloat during the crisis. Remarkably, during COVID, operating margins were 200 basis points higher than they had been before the pandemic. And with that, their net profit would actually grow 115.6% in FY21.

A return to normal

Eventually, demand would return, and companies would jump back into action. Corporate India’s profits would shoot up in the coming years. From ₹2.5 trillion in FY 2021, they would grow to over ₹7.1 trillion by FY 2025.

They would also quickly resume creating value. After contracting 5.3% in 2020-21, corporate India’s “gross value addition” roared back with 20.4% growth in 2021-22.

But their recovery was far from straightforward. While demand had returned, their expenses went back up as well. Commodity prices increased once again — even rising somewhat as many supply chains frayed. In FY 2022, their raw material expenses jumped back up, by 47.6% year-on-year. Staff costs, too, were up in the double digits. In the years since, companies’ personnel costs have gone back to where they were before the pandemic, while their raw material costs actually inched up from the pre-pandemic trend.

Some industries would take exceptionally long to recover. Consider non-IT services. Many of these would have to be delivered in person — and over repeated waves of COVID, struggled to turn a profit for years. IT services, too, saw a peculiar trajectory. While they did well during the pandemic, since then, activity has come down, dragging down margins with it.

But in the aggregate, the Indian economy has done an exceptional job of defending its margins. With manufacturing, in particular, leading the way, by Fiscal 2025, margins had entered double digit territory.

How was that achieved? The RBI points to a change in the attitude of corporate India.

A change in attitude

The RBI analysed data from over 1,100 listed companies across 11 industries, to try and understand how companies got to their operating margins.

Before COVID, there was a strong relationship between sales growth and margins. That is, companies were chasing growth, and that’s where their profits were coming from. After COVID, however, that relationship has inverted. That is, companies sacrificed sales growth while protecting margins. Having survived a near-death experience, they’ve turned cautious about expansion, focusing on sustaining profits rather than growth for growth’s sake.

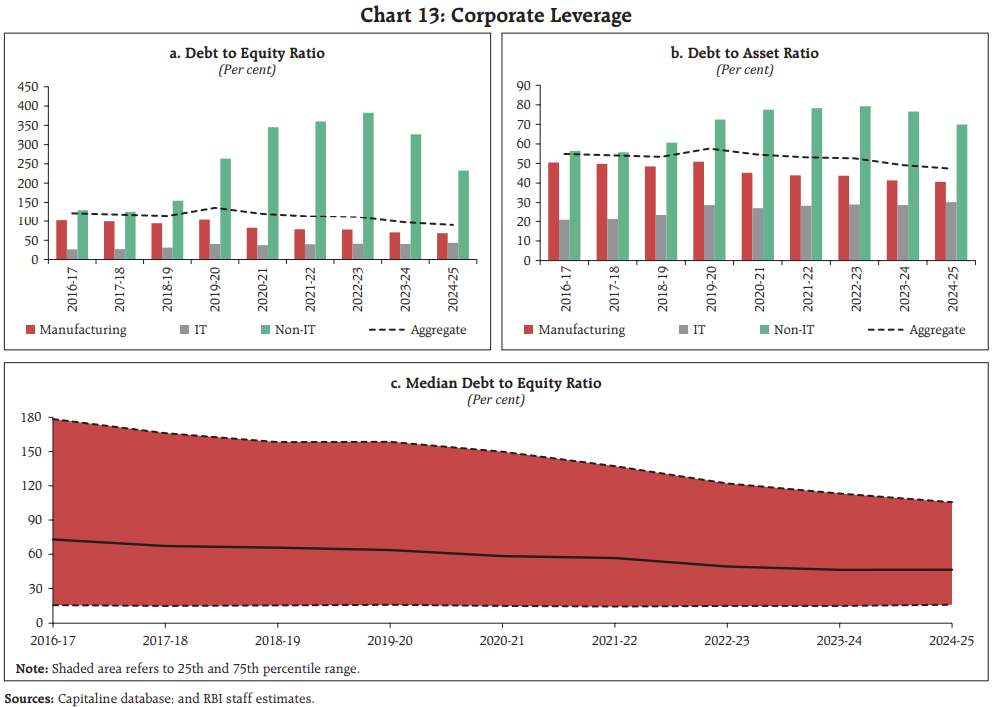

This caution also shows up in how heavily companies have focused on cleaning up balance sheets, and bringing down their debt load.

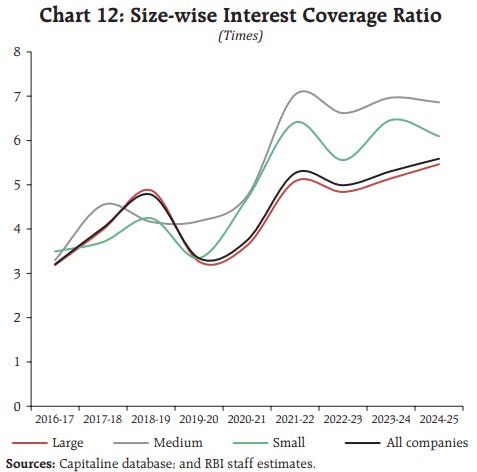

As companies’ profitability recovered, they’ve made a serious attempt at improving their interest coverage ratios. Manufacturing companies, for instance, improved their ICR from around 4 times, pre-COVID, to 7.7 times post-pandemic. That is, they can now pay their interest bills nearly eight times over from what they earn. Non-IT services were the worst hit during the pandemic, dropping under the red line of 1. But as soon as cash flows improved, they brought their ICRs above 1.

In fact, small and medium businesses were the most enthusiastic in repairing their balance sheets. While large firms maintained the highest operating margins, driving the bulk of profits alone, medium and small firms improved ICR faster.

The debt-equity ratios of corporate India, too, have improved drastically across the board. For large companies, these plunged from 139.2% in FY 2020 to 94.0% by FY 2025. But once again, smaller companies achieved even more dramatic improvements, with their debt-equity ratios almost halving from 115.2% to 66.1%.

The same caution is also evident in how companies are making investments. Since the pandemic, companies have focused on retaining their earnings, instead of plowing them into acquisitions or giving away huge dividends. Most of their investments, moreover, have been in fixed assets and long-term financial products. Their speculative exuberance has gone, it appears — they’re instead trying to create “fortress balance sheets.”

The metamorphosis

Corporate India began the COVID pandemic on the back foot. Things were already slow in FY 2020, and the pandemic ratcheted up our economy’s problems. Without the RBI stepping in to intervene actively, a large part of our corporate sector could have been in dire straits.

But ultimately, the RBI’s paper conveys a picture of resilience. Although conditions have remained difficult in the years since, Indian firms, too, have adapted — growing tougher and more disciplined. A once-in-a-lifetime shock has taught them to relearn the basics. While maintaining growing revenues, they’ve held on to their profit margins, and have actively deleveraged to strengthen balance sheets. The crisis of COVID-19, interestingly, has made them less fragile and vulnerable than they once were.

This doesn’t mean success will come any easier, or that they’re immune to the next crisis. But, for that, their odds are better than they were before. That is a victory in itself.

Tidbits

Punjab National Bank may take a hit worth $1 billion as the RBI is considering changing provisioning rules for banks. CEO Ashok Kumar has said that the bank is positioned well to absorb this hit comfortably. As we covered very recently, the RBI will gradually move from an incurred-loss provisioning framework to an expected-credit loss one. PNB is one of the first to declare the impact of this shift on their finances.

Source: ReutersIndia’s infrastructure output slows to its lowest in three months in September, growing only 3% year-on-year. The index tracks 8 sectors, and its slowdown was driven by declines in the output of crude oil, natural gas and refinery products.

Source: ReutersHeineken warns that its beer sales would only continue to fall as macroeconomic challenges worsen. It expects its annual operation profit to be in the lower end of the 4-8% range, and its stock has been sliding down. Its volume fell by 4.3% in the third quarter of this year.

Source: ET

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Assam has a high penetration of smart meters. Also, the government has changed to Pre-paid billing. If you forget to recharge, you get disconnected and the your electricity connection resumes within 15 minutes of recharge.

https://open.substack.com/pub/earningsunwrapped/p/watts-up-with-smart-meters?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=rer2b

Wrote about this industry sometime back, humongous scope, still some variables with respect to policy implementation.