India’s Economy: The Big Revelations

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

By the way, if you want to understand what happened in this year’s budget, we released a video on it here:

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Where is our economy, and how can we fix it?

Life Insurance Companies are going through temporary hiccups

Where is our economy, and how can we fix it?

Every year, on the day before the Finance Minister’s budget speech, the Finance Ministry comes out with an ‘Economic Survey’. This survey, prepared by India’s Chief Economic Advisor (or CEA), is one of the most important annual commentary on India’s economy. It shows you how the government’s best economic minds think about things and their ideas about what India’s future path should be.

There are three things you should look to any economic survey for: (a) a comprehensive look at how different parts of the economy are doing, (b) India’s biggest economic challenges, and (c) the CEA’s suggestions on steps India could take to boost its economy.

This year’s Economic Survey comes a mere six months after the last one. The context of the two surveys, however, could hardly be more different. Over the last year, the outside world has become increasingly uncertain — a bad environment for India’s growth.

Thus far, India has survived this uncertainty fairly well, with strong agricultural prospects and robust services growth. But the picture isn’t too rosy either. Foreign investments into India, for instance, are drying up. Our manufacturing sector has seen limited growth. The rise of AI can create unprecedented challenges for our services industry. The one thing the Survey highlights, beyond doubt, is that this is a make-or-break moment for the country.

Unless you have ten hours to spare, there’s no way we can compress this 450-page report into something that’s easily digestible. For a full picture, consider skimming through it yourself.

Instead, we’re going to look at what are, to us, the five most important observations the survey makes about our economic troubles, and what we can do about them. Let’s begin.

Excessive financialisation of the Indian economy

In recent years, India has seen its financial sector boom. Indian companies are increasingly turning to financial markets, and not banks, for their funding needs. This is something we have waited a long time for. Finance, after all, is the brain of any economy. It routes people’s savings to those who can make the best use of it.

But this is an inflection point. As Indian finance blooms, we’ll need to tread carefully.

As the Economic Survey points out, there’s such a thing as too much finance. For instance, when Ireland’s finance sector grew too fast in the early 2000s, that caused its productivity to lag. Thailand, on the other hand, saw the opposite happen — its financial sector shrank during the Asian financial crisis, but this only made its economy more productive.

There’s a Goldilocks zone (see the graph above) — one where the finance sector is neither too large nor too small, but just right — which makes an economy function optimally.

Why so? See, an overly large financial sector ends up competing with the rest of the economy for resources. The economy’s most skilled workers, for instance, end up in finance jobs, starving other sectors of their talent. If the finance sector is too big for an economy, it can end up innovating bogus products that send money into projects that do nothing for the economy. These ‘innovations’ can be deeply dangerous, as we learned during the 2008 financial crisis.

This is a trap that India must avoid. It needs a healthy finance sector, without compromising on the stability of the economy. How can it do so? The Economic Survey thinks regulatory innovation is the answer. Digital infrastructure, such as the Open Credit Enablement Network or the Unified Lending Interface can make finance easier, without giving financial firms the leeway to take unnecessary risks.

Is India still investible?

The Economic Survey paints a concerning picture around India’s ability to draw investment.

Net FDI, for instance, plummeted to just USD 0.48 billion between March and November last year, from USD 8.5 billion over the same months in 2023. To be fair, gross FDI inflows have actually increased by 17.9%. A lot more investment, though, is being repatriated to where it came from.

This is, in a way, a good thing — it means India now has a proven track record of letting investors make profits. However, unless more money flows in, we’ll struggle to meet our needs for growth.

So, why are we struggling so much to pull in investment? At least part of the answer lies in how over-regulated business in India is. In fact, the Survey cites Mario Draghi’s indictment of Europe — which we covered a few days ago — saying that India suffers many of the same problems.

Consider our textile sector, for instance. Indian textiles, for most of world history, have been sought after all over the world. It remains the perfect industry for a country like us — creating lots of jobs with low skill requirements. Today, however, India commands just 2.8% of the global apparel market. We’re significantly behind China (30%), Bangladesh (9%), and Vietnam (7%). The Survey finds that while around USD 3 billion worth of India’s apparel exports are world-class, the rest of our textile sector struggles against our competitors. And that shows in how our textile exports are stagnating:

Why? Well, India’s textile industry suffers from terrible structural issues. While competing nations boast of vertically integrated 'fibre-to-fashion' firms, our textile production is fragmented across multiple SMEs. This makes us both costly and inefficient. We have put all kinds of complex regulatory procedures in place — for instance, exporters have to meticulously account for every square centimeter of fabric, buttons, and zippers used. India’s competitors simply do not have such bureaucratic bottlenecks.

The Survey suggests a two-pronged approach to address these challenges. First, India needs to "pull out all the stops" in making itself attractive to foreign investors. Foreign investors constantly look at how India compares with competing nations — and we need to make the best possible case for ourselves.

Second, and perhaps more crucially, if we can’t control the amount of investment into India — if investors are too spooked by global uncertainty, for instance — we must focus on improving the efficiency of every dollar that does come in. This may require comprehensive deregulation. In fact, within India, states that have pursued policy reform have slowly come to dominate Indian manufacturing:

Inflation trajectory diverging from the world

India's inflation figures, in 2024, were in stark contrast to global trends. As the Economic Survey notes, while global inflation steadily declined from its 2022 peak of 8.7% to 5.7% in 2024, India’s inflation trajectory has been more chaotic. This is largely the result of food prices. While most major economies are seeing food prices stabilize or decline, India remains one of the few emerging economies, alongside Brazil and China, bucking this trend.

Food prices have an out-sized impact on India's overall inflation. Consider this: vegetables and pulses, which make for a little more than 8% of our CPI basket, caused one-third of the overall inflation in FY25. When these items are excluded, the headline inflation drops from 4.9% to 3.2% – a significant 1.7 percentage point difference. This outsized impact of select food items points to deeper structural issues in India's food supply chain.

As per the Survey, there are two key factors driving this divergence:

One, climate change has emerged as a major disruptor for Indian agriculture. India experienced heatwaves on 18% of days during 2022-2024, compared to just 5% in 2020-2021. There’s a clear correlation between extreme weather events and spikes in vegetable inflation, with effects lasting up to three months.

Two, India's agricultural supply chain is deeply fractured. Even though we grow more onions and tomatoes than we consume, prices remain volatile.

The findings suggest that India needs a two-pronged approach: one, India needs immediate measures to handle short-term price pressures, and two, India needs long-term structural reforms to improve agriculture.

Geo-economic fragmentation

The global economy is witnessing a fundamental shift from hyper-globalization to what the Survey calls "geoeconomic fragmentation." Between October 2023 and October 2024, WTO members introduced new trade restrictions covering $887.7 billion worth of trade, more than doubling from the previous year's $337.1 billion. Unlike the Cold War era when trade was just 16% of global GDP, today it stands at 45%. If we revert to Cold War-like conditions, the repercussions will be severe.

At the heart of this challenge lies China's overwhelming dominance in critical industries. For instance, China controls over 80% of solar panel manufacturing, 60% of wind capacity, and 80% of battery manufacturing globally. For India, this creates particular vulnerabilities - it sources 75% of its lithium-ion batteries from China and has negligible domestic production capacity for key green technology components. This dependency will only become more critical as India aims to achieve its energy transition goals.

The Economic Survey suggests a pivot towards strengthening domestic growth drivers. To achieve its target of 8% annual growth, India needs to raise its investment rate from 31% to 35% of GDP. However, in an increasingly fragmented global economy, we cannot merely rely on increasing investment volume — we must improve the efficiency with which this money is spent. This requires systematic deregulation, particularly at the state level, and building robust domestic supply chains in strategic sectors. This will be challenging, but it is necessary to adapt to new global economic realities.

India must prepare for AI taking over jobs

India faces a daunting employment challenge. It needs to create 78.5 lakh jobs annually in just the non-farm sector by 2030 to absorb its growing workforce. Now, add artificial intelligence to this equation. Recent surveys paint a concerning picture: 68% of white-collar workers in India expect their jobs to be partially or fully automated within five years, with 40% believing their skills will become redundant.

What makes India particularly vulnerable is its economic structure. As a services-driven economy, India is exposed to white-collar automation in ways that manufacturing-led economies might not be. A significant portion of India's IT workforce is employed in low value-added services - precisely the kind of work most susceptible to AI automation. We're already seeing early signs: companies like PhonePe have cut 60% of their support staff as AI drives efficiency gains. Moreover, India's entire economy is consumption-driven. Job losses could trigger a dangerous downward spiral — when workers lose jobs, they consume less, which hurts businesses, leading to more job losses.

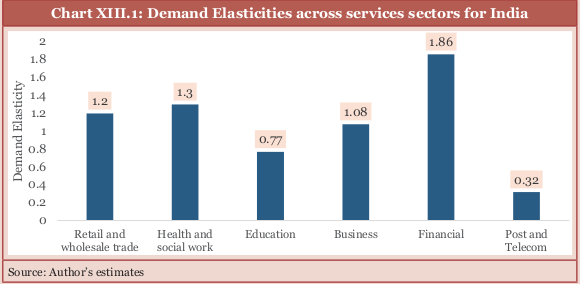

However, the survey's analysis shows demand may stay high in key service sectors — like financial services, health and social work, retail and wholesale trade, and business services. This means that while AI drives productivity gains, these sectors might actually expand employment rather than contract it — provided we manage the transition well.

For that, India will need to build three types of institutions: "enabling" institutions for workforce skilling, "insuring" institutions to provide safety nets, and "stewarding" institutions to govern AI deployment. But time is of the essence. The success of India's AI transition will ultimately depend on how quickly we can build these institutional frameworks.

Life Insurance Companies are going through temporary hiccups

Private life insurers have released their results, and we thought we would give you a glimpse of what is unfolding. Insurance is a complex sector, and we are far from experts, so we will focus on just a few points that should matter to anyone starting to learn about this space.

Let’s begin with the industry-level growth rates, specifically the APE (Annual Premium Equivalent) growth rates. APE is similar to the revenue equivalent for insurance companies; it gives us an idea of how much premium these players are collecting.

Overall, the industry declined by 2.3% for the quarter, while it grew by 13.8% year over year. This suggests that something happened in the most recent quarter that caused a hiccup in the long-term growth story. Going more granular, LIC dragged the industry down by declining 27.3%.

This was mainly because group insurance premiums nearly halved for LIC. An insurance company caters to two types of customers: individual and group. Individual insurance targets people like you and me who buy policies for personal security, while group insurance covers multiple individuals under a single master policy. Group insurance is often offered by employers, associations, or financial institutions.

Group business makes up around 33% of LIC’s total revenue, so it took a hit. The reason? There was a spike in APE in December 2023 from a large client group, which has now normalized. If you compare numbers with December 2022, LIC still shows positive momentum.

But you see, even private insurers saw their APE growth dip, mostly due to factors beyond their control. Here are a few plausible explanations:

IRDAI had revised norms for those looking to surrender a life insurance policy and that could facilitate a better exit payout for customers. This basically doesn’t only affects margins for the insurers because they will have to dole out more money than before, but also affect their growth rates. Why? Because The new surrender value norms introduced by Irdai will apply primarily to new endowment policies and since this rule will provide greater flexibility and liquidity for life insurance customers who want to switch policies, it is less likely that they will be missold the policies they didn’t need in the first place. Now that is a stretch in the hypothesis that was being made by media and research reports, but sounds plausible.

Also, private life insurers depend heavily on banks to sell their policies, especially their parent banks (like HDFC Bank for HDFC Life). More than half of HDFC Life’s and SBI Life’s sales come from bancassurance. Now that deposit growth has slowed in the banking system, banks have likely been pushing traditional banking products over insurance products, as pointed out by Care Edge Ratings. There are also rumors that IRDAI might cap bancassurance contributions at 50% of an insurer’s revenue, which could become another pain point.

That said, it’s not all doom and gloom if we take a step back. Let’s look at the three largest private insurers.

If we rank them by APE, SBI Life is the largest, followed by HDFC Life and ICICI Prudential. But in terms of APE growth over the past year, ICICI Prudential leads at 27%, followed by HDFC Life at 20%, and SBI Life at 11%. Smaller players often find it easier to grow faster, but there’s more to it than just size.

What explains these different growth rates? It comes down to which products they sell and how they distribute them.

ICICI Prudential

ICICI Prudential is the fastest-growing player right now, partly because its ULIPs (market-linked savings plans) grew nearly 50% year-on-year. ULIPs blend insurance and investment and make up around half of ICICI Prudential’s total business. Customers seem to be chasing market-linked returns, boosting sales. However, ULIPs usually offer insurers low margins since they’re more like investment products than traditional insurance, and underwriting is minimal, so fees are limited.HDFC Life

HDFC Life is seeing its non-par savings products grow 55% year-on-year. These products act like a savings plan with guaranteed returns and fixed maturity benefits but don’t offer any share in the insurer’s profits. Typically, they attract risk-averse customers. Margins are higher compared to ULIPs because the customer doesn’t participate in the insurer’s profits.

While ULIPs are ICICI Prudential’s biggest draw, HDFC Life focuses on these other segments with potentially higher margins. Its share of ULIPs has dropped from 36.9% in March 2024 to 32.3% in December 2024.

3. SBI Life

SBI Life, India’s largest private insurer, also relies heavily on ULIPs, which make up about two-thirds of its business and grew by 21% over nine months. But other segments declined—group savings fell 30% and individual protection fell 19%—bringing overall growth to just 11%.

Like ICICI Prudential, SBI Life has invested in its agency channel, which grew 28%, but bancassurance, mainly through SBI’s branches, still accounts for 63% of its sales and grew by only 7%.

A common trend is that ULIP sales have been the main driver of premium growth for these insurers so far, likely due to strong market performance. However, when markets turn volatile, ULIP demand typically falls. That effect often appears with a nine- to twelve-month delay. With markets looking somewhat unstable now, ULIPs could falter if volatility persists.

Tidbits

Whirlpool Corporation plans to reduce its stake in Whirlpool of India from 51% to 20% by the end of 2025 through a market sale. The move is expected to raise $550-600 million, helping the company repay $700 million in debt next year. Following the announcement, Whirlpool of India’s stock took a sharp 20% hit, closing at ₹1,260.80 on the NSE.

JK Paper has acquired a 65% stake in Quadragen VetHealth for ₹460 crore, marking its fourth acquisition in just 2.5 years. Quadragen VetHealth, with an EBITDA margin exceeding 30% and a 20% CAGR, offers a high-margin business that contrasts with JK Paper’s struggling paper segment. In Q3 FY25, JK Paper’s net profit plummeted to ₹65.39 crore from ₹235.11 crore a year ago, highlighting the need for diversification.

Adani Enterprises Ltd. reported a staggering 97% YoY decline in net profit for Q3 FY24, falling to ₹57.83 crore from ₹1,888 crore in Q3 FY23—the company’s worst drop in three years. Revenue dipped 9% to ₹22,848 crore, largely due to a 44% slump in coal trading revenue (₹8,980 crore) and forex losses of ₹296 crore from its Australian operations.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav, and Kashish

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

New tax regime will impact insurance companies. Earlier in old regime, people used to buy lic for 80c and medical for 80d, now, such deduction and 18% gst on those products, we might see dip.