India’s airport industry fights to stick the landing

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads-up before we dive in. The Meesho IPO is open now. We wrote about them earlier — you can read the full story on Meesho here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The long and winding journey of India’s airport industry

Inside the credit rating business

The long and winding journey of India’s airport industry

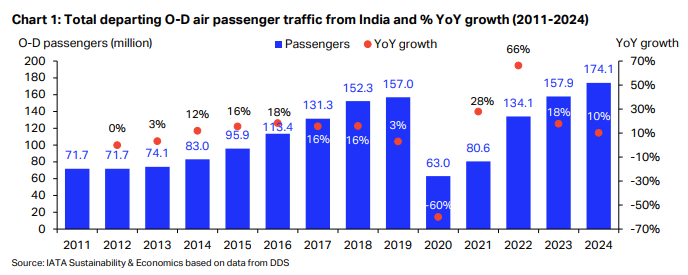

India’s airports are busier than they’ve ever been. Between 2011-2019, they logged an impressive double-digit growth rate, reaching a peak of 157 million passengers in 2019. While CoVID-19 dampened global air travel, India rebounded strongly in just 3 years. And it’s expected to continue its excellent run.

It’s on the back of this growth that Adani Airports, India’s largest private airport operator, said that by 2030, it shall invest $15 billion on airport infrastructure.

This might nudge you to think of gleaming terminals, world-class lounges and other luxuries. But behind those polished facades is a complicated, constantly-evolving policy experiment. At the heart of this experiment is a dilemma. On one end, airports want the freedom to price and make profits. On the other, both airlines, who pay those fees, and the government, which wants air travel to be affordable for passengers, want those fees to be reduced.

This experiment has changed shape multiple times. And understanding it explains a lot of things: from why your airport coffee costs so much, to how even the largest airport operators can be brought down to their knees.

The evolution of Indian airports

To understand the Indian airport business, let’s take a little history lesson.

The PPP model

For most of independent India’s history, airports were government-run. The Airports Authority of India (or AAI) owned and operated everything. But these often looked old and dilapidated. And by the 1990s, it was increasingly clear: the government simply didn’t have the funds to modernize our airports.

As India liberalized over the 1990s, airports went down the route of public-private partnerships (PPP). This would bring in private capital and expertise, while the state provided land and security. Both would share revenues. In 2006, GMR Group won the bid to modernize the Delhi Airport; while GVK Group won Mumbai. Around the same time, greenfield airports in Hyderabad and Bengaluru were developed by private-led consortia.

The model seemed to work. These cities now have world-class terminals that are also among the busiest in the world.

But there was a catch. The AAI got a really high revenue share, raking in 46% of gross revenue at Delhi and 39% at Mumbai. Nearly half of every rupee the Delhi Airport earned, for instance, would never come to the private operator behind the scenes.

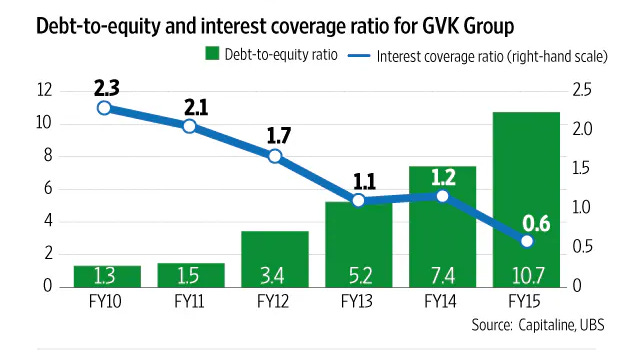

Meanwhile, those airports require a lot of capex, often funded by debt. Often, operators found themselves crushed under the burden of rising interest payments. For instance, GVK Group, the former operator of the Mumbai Airport, was forced to sell off their airports due to debt.

One privatization after another

By 2019, the government wanted to raise more funds to run their existing airports. That meant inviting more private capital. But drawing them in needed a major shift in the business model.

And so, instead of revenue-sharing under the PPP model, bidders for new airport leases would now pay a per-passenger fee (PPF) to be paid to AAI. This gave them transparency: it was easier to plan around a fixed fee per passenger, rather than a percentage of unpredictable revenues. The government held PPF bids for 6 airports — with the bidder promising the highest PPF winning the right to operate an airport for 50 years.

This heralded the arrival of a new player: Adani. To the industry’s surprise, Adani Airports swept all six airports on offer, with aggressive bids that more than doubled competitors’ offers. For Ahmedabad, for instance, Adani bid ₹177 per passenger versus GMR’s ₹85. And by 2021, Adani took over ownership of the massive Mumbai airport from the distressed GVK Group.

Money for nothing

As privatization took over the airport industry, an age-old conflict emerged: should crucial infrastructure like airports be run purely for-profit? Or, much like Railways, should they also be seen as social service?

After all, airports are geographic monopolies. A city can realistically support only one airport — or two at most, if the city is very big. Every passenger from that city has to use them. This makes airports akin to essential public infrastructure. If private operators get unchecked pricing power, these passengers will have no choice but to pay them. This is why, despite increasing privatization, the government has always regulated how airports make money.

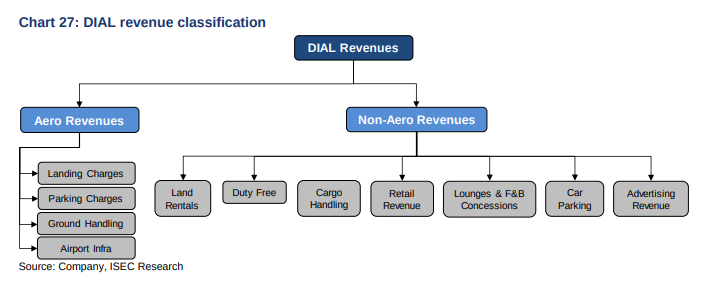

To understand this better, let’s break down how airports earn. This can broadly be bucketed into two categories.

The first category is aeronautical revenue, which is directly related to flying operations: like landing fees and parking charges against airlines (which usually pass it on to passengers). These are regulated by the Airports Economic Regulatory Authority (AERA), which sets aero tariffs every five years to ensure operators earn a “fair“ return without gouging airlines or passengers.

The second category is non-aero revenue: money from hosting retail shops, restaurants, car parking, advertising, international duty-free and real estate. In theory, these aren’t price-regulated — airports can negotiate whatever deals they want with tenants.

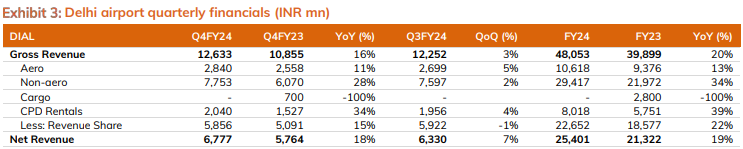

In fact, with the liberalization of the airport business, non-aero revenue has taken as much (more, in some cases) importance as aero revenue. Since aero revenue is generally subject to price ceilings by the regulator, non-aero offers the only flexible way to make profit. In fact, over 60% of Delhi Airport’s business, for instance, comes from non-aero revenues — nearly triple that of aero revenues.

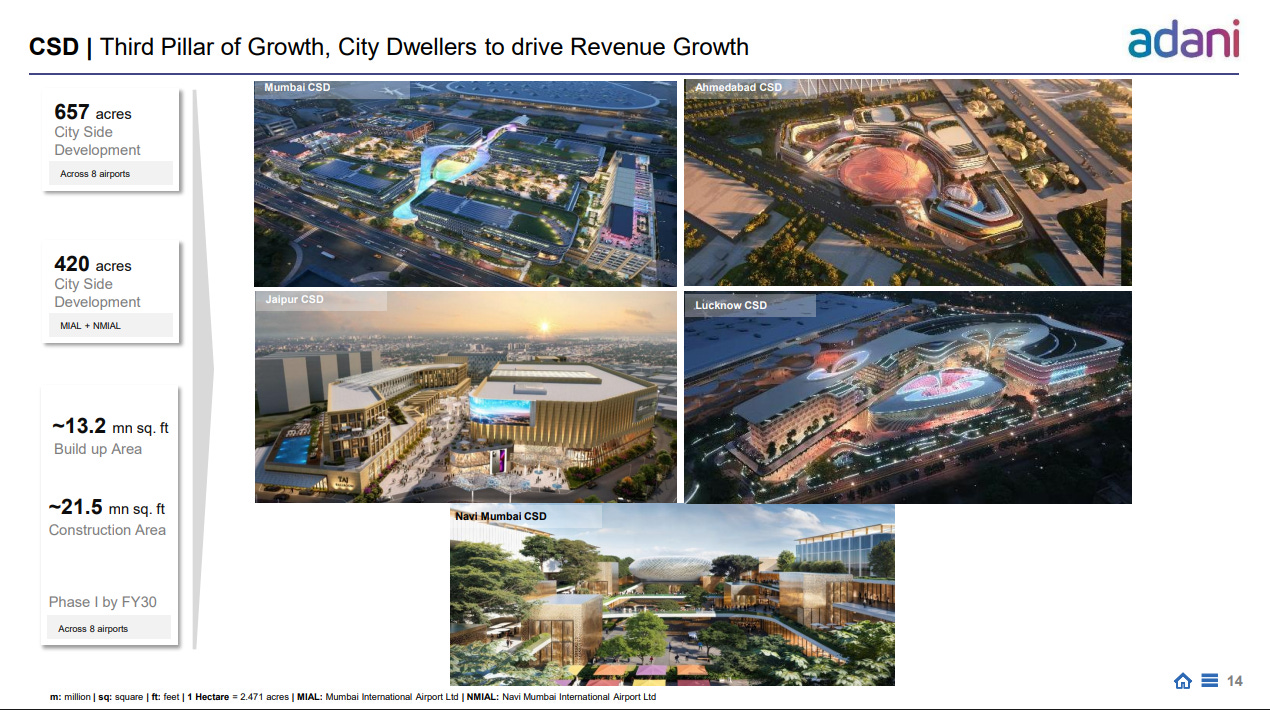

Real estate, in particular, is a massive source of non-aero revenue. Big airports sit on hundreds of acres of prime land, which can be used to develop projects like luxury hotels, office parks and warehouses. This was a big reason that Adani — which already has a strong real estate business — entered the airport industry.

Single-till vs dual-till

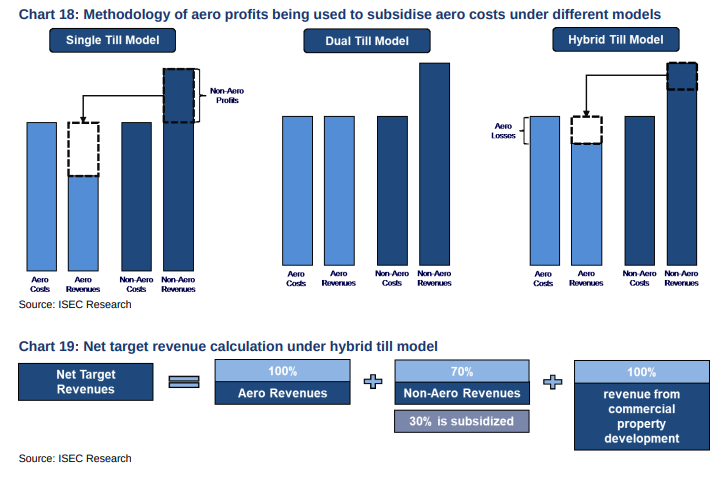

In practice, for the longest time, non-aero revenues were regulated, but indirectly. Understanding this requires grasping one of the most crucial debates in airport policy: should revenue sharing be single-till or dual-till?

Imagine you run an airport that, in a year, earns ₹100 crore in fees from airlines, and ₹50 crore from non-aero sources. Under a single-till regime, both revenue streams are pooled together when the AERA is setting tariffs. If the airport’s non-aero business is booming, AERA will factor that in and lower the landing fees airlines are charged.

As the argument goes, non-aero revenues don’t exist without flights. After all, flying is the most important purpose of an airport. Without that, airport food and shopping doesn’t exist. So, excess profits from shops should subsidize flying costs.

Under a dual-till regime, though, the two are treated separately. Aero tariffs are set based only on aviation costs. The airport keeps all its retail profits without worrying about them hurting plane-landing fees.

Single-till benefits airlines and passengers with cheaper flying, but limits airport profitability. Dual-till is the reverse — airports keep their commercial upside, but flying may get more expensive.

For a long time, India followed single-till. However, in December 2015, a crisis reshaped the entire regulatory framework.

When AERA set Delhi Airport’s tariffs for 2014-2019, it applied the single-till formula strictly. The regulator determined that the airport was earning too much — partly because of an aero tariff hike from earlier, and partly due to booming non-aero retail income. As a result, AERA ordered an ~89% average reduction in aero charges. The “user development fee” passengers paid, for instance, was slashed from ₹275-550 to just ₹10. Arriving passenger fees were eliminated entirely.

This left airports deeply unhappy. Delhi Airport argued this would make operations unviable and trigger loan defaults. The decision was challenged in court, creating years of regulatory uncertainty.

In response, the government introduced a “hybrid-till” model in 2016 — a compromise between single-till and dual-till. Under this model, only 30% of non-aero revenues would be used to subsidize aviation tariffs; while the operator keeps the rest 70%. The hope was that this left some incentive for airport operators, and some social benefit.

India is now one of the few countries where every large airport within its borders is mandated to follow this 70-30 model. Elsewhere, individual airports often have their own arrangements. London’s Heathrow Airport, for instance, operates on single-till, while many other British airports are either dual or various versions of hybrid-till.

Whither profit?

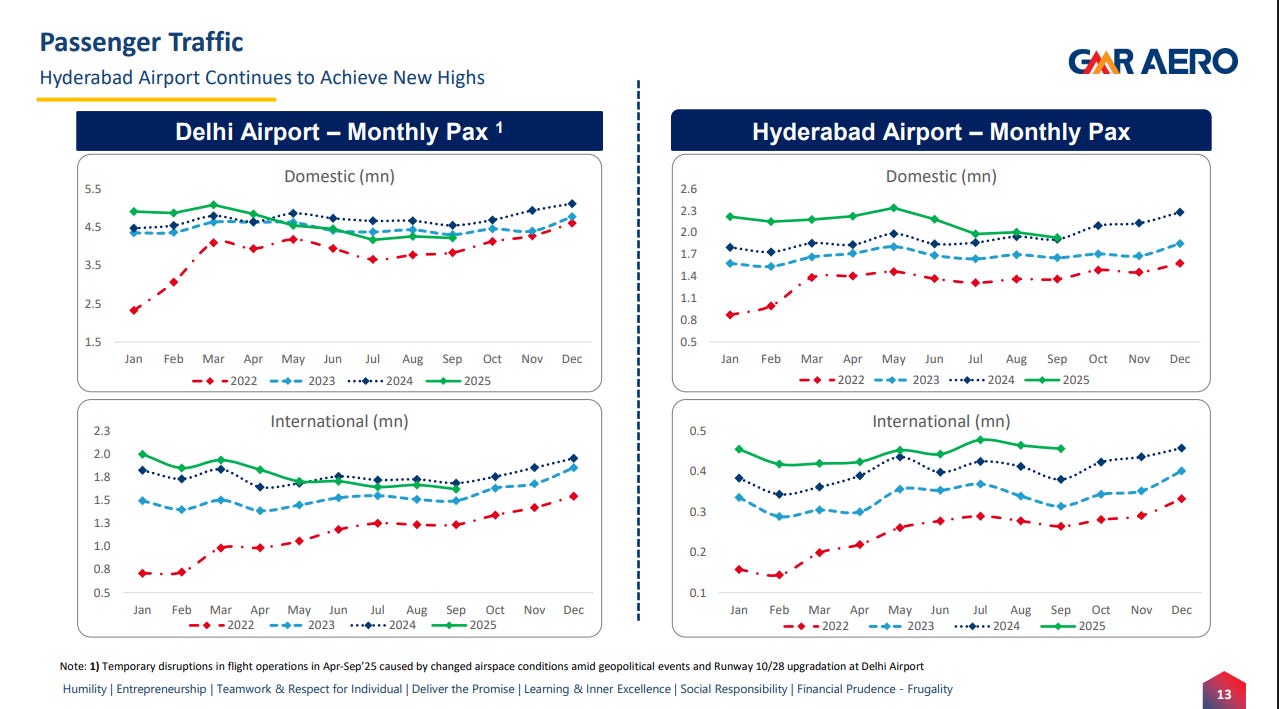

Since the pandemic, airport finances have been getting better — partly due to the hybrid-till model, and partly due to hikes in aero tariffs. For instance, just last quarter, GMR finally scored one of its highest quarterly EBITDA margins. Adani, meanwhile, recorded a 43% increase in EBITDA in FY25.

Net-net, however, most airports continue to be in the red. Hybrid-till hasn’t done enough to change the fact that airports still bleed money every year, regularly recording negative PAT.

This is partly because the government continues to take a massive cut of the revenues. Not profit, by the way, but revenues — meaning that this is a large and immediate expense for airport operators. These payments are why AAI, a PSU with volatile finances, profitable in recent years.

This risk continues with the PPF model, albeit in a different way. Now, these airports have to pay AAI for every passenger that enters an airport, losing money unless that passenger uses their restaurants or shops.

The second is that airports’ dependence on non-aero revenues means that they’re constantly trying to maximise everything outside of airline fees. Airport restaurants and retail, for instance, operate on razor-thin margins — because they must pay steep rents to the airport operator, who in turn is trying to maximize non-aero income, because aero tariffs are capped. This, perhaps, is why your airport coffee costs so much.

Indian airports also underperform global peers on non-aero. Major Indian hubs averaged just $4.3 of non-aero revenue per passenger in 2023-24, compared to $7-14 at global airports. Indian travelers are cost-sensitive—they browse duty-free but spend relatively little on luxury goods. Indian airports also tend to get more domestic passengers rather than international ones, who are likely to spend more on a trip.

The third reason is one we briefly mentioned earlier: airports are debt-heavy businesses that also depreciate. Terminals, runways, parking structures—all require massive upfront capital, typically funded by debt. And that debt servicing often needs raising more debt — GMR, for instance, is still paying off its old loans by raising new bonds.

Up in the air

India’s airports look and feel premium. But behind the scenes, they operate as high-capex, high-debt, heavily-regulated utilities with thin margins — even after privatization.

The state regulator faces a constant balancing act: encourage private investment while preventing monopoly abuse and keeping air travel affordable. And that requires a lot of experimenting, failing, and trying again. They’ve adjusted accordingly, too: the shift from single-till to hybrid-till was one such idea. The move from revenue-share to per-passenger fees was another.

But they haven’t reached an equilibrium. Things will get increasingly complex as tier-2 cities take up a bigger share in air traffic, as we’ve written about before. But maybe the trick, as India has done so far, is to not figure out a single winning formula, but constantly adapting to newer contexts.

Inside the credit rating business

We’ve covered large parts of the financial world before, on The Daily Brief — banks, stockbrokers, mutual funds, or even insurance companies. There’s a critical capital markets player, though, that usually stays outside the limelight -– credit rating agencies (CRAs).

These are the invisible gatekeepers of finance. They don’t lend money, or facilitate transactions. Their core product is an opinion — a credit rating — on how likely a borrower is to pay back debt. This simple service has huge implications. A single decision by a rating agency can literally move markets.

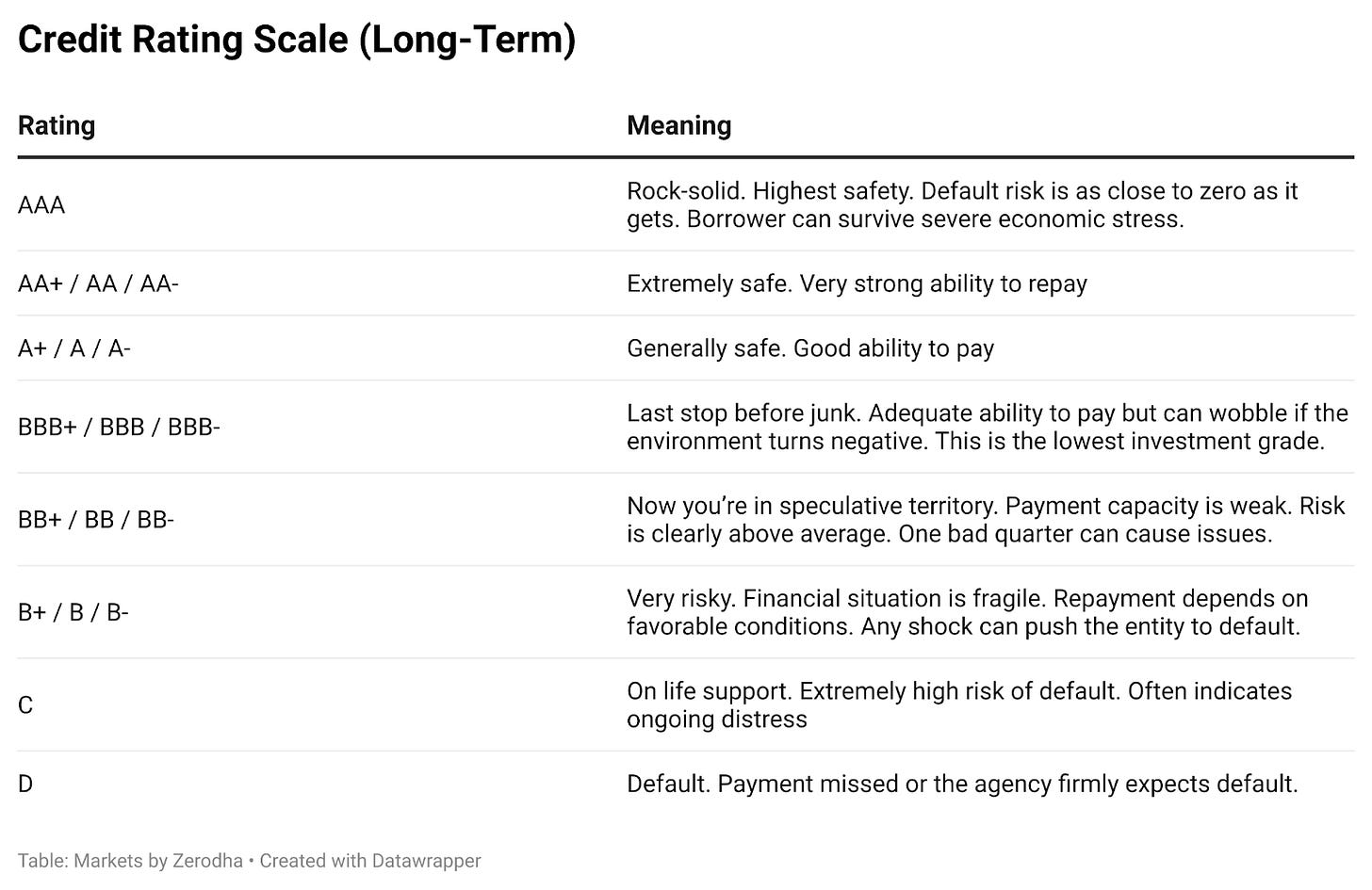

We saw this in action this August, when S&P Global Ratings upgraded India’s sovereign credit rating from “BBB-” to “BBB”, the first time in 18 years. Markets reacted immediately. The Rupee suddenly firmed against the dollar, while yields on 10-year government bonds fell by ~7 basis points.

Despite this power, though, CRAs are poorly understood. So, today, we decided to learn about them, from the ground up. Let’s dive in.

What do credit rating agencies do?

CRAs evaluate the creditworthiness of borrowers — whether they’re governments, companies, or even specific debt instruments. Put simply, they ask: how likely is this borrower to default on their borrowings?

Based on that, they assign a rating. These range from the highest grade, AAA (indicating extremely low risk of default) down through AA, A, BBB (the cutoff for “investment grade”), and downwards — all the way to D (default).

A good rating is a stamp of approval. It signals to lenders and investors that “this borrower is solid and will most likely repay on time.” A poor rating, meanwhile, points to significant risk.

None of this is a guarantee. CRAs are just professional, SEBI-registered opinion-givers. But in a world that’s constantly on the hunt for safe spaces to park their money, even a mere opinion from a trusted voice can go a long way. It can move trillions of dollars in capital worldwide, by influencing what investors buy, and the interest rates companies pay.

There’s only so much money that ratings alone can bring in, however. And so, many CRAs have diversified into related services — usually playing off their reputation for research and risk assessment.

For instance, many CRAs produce in-depth research reports, offer risk management and analytics solutions, provide advisory services, or give out ESG (environmental, social, governance) ratings. Think of these as side hustles. After all, CRAs already pour over companies’ and governments’ finances. They already have a large base of knowledge that they could repurpose into research reports. Apart from bringing in extra revenue, these additional business lines also help smooth out what can be a rather lumpy business.

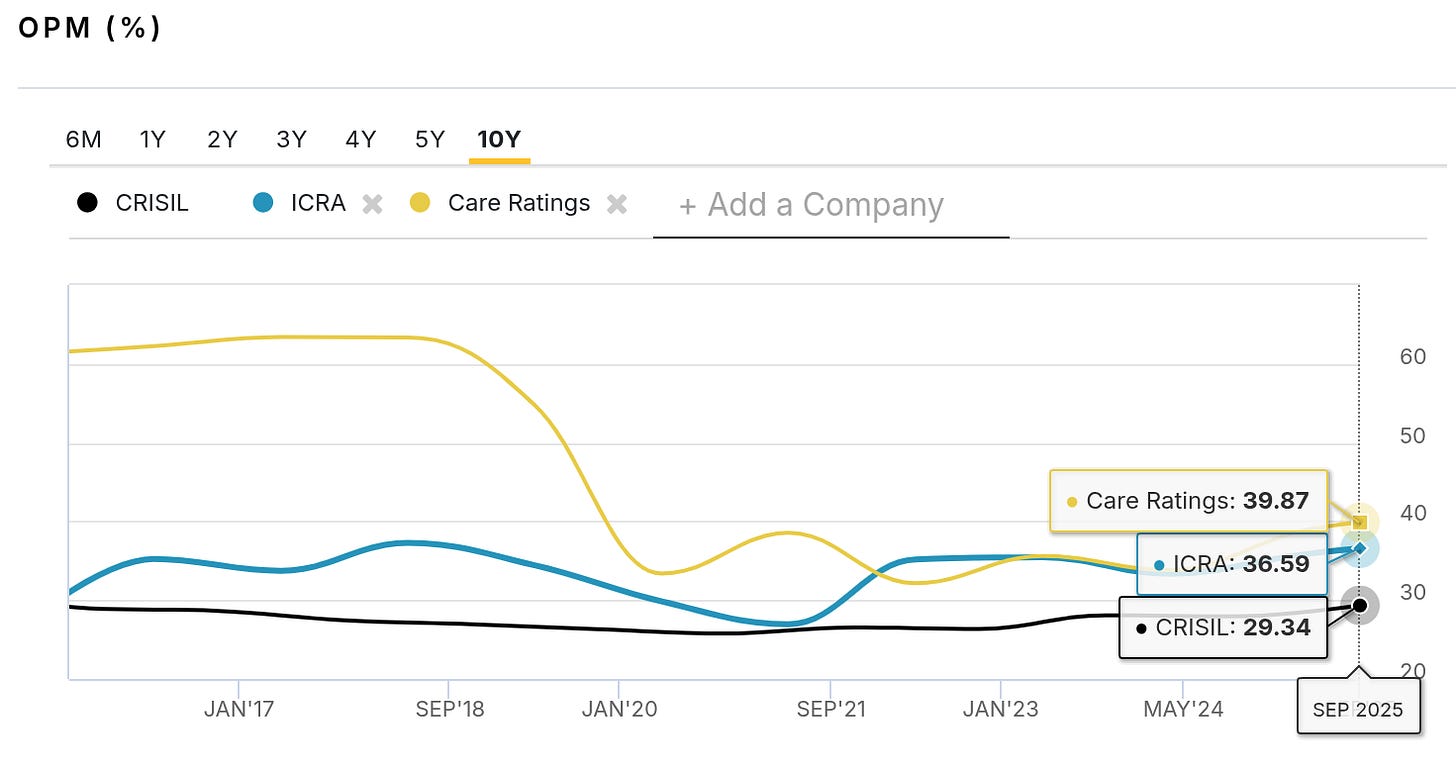

Structurally, though, these side hustles usually come with far lower margins than ratings. After all, ratings are where they have pricing power — they’re protected by regulations and credibility, letting them charge well. These other business lines, in contrast, are all crowded — with competition from consulting firms and boutique analytics shops.

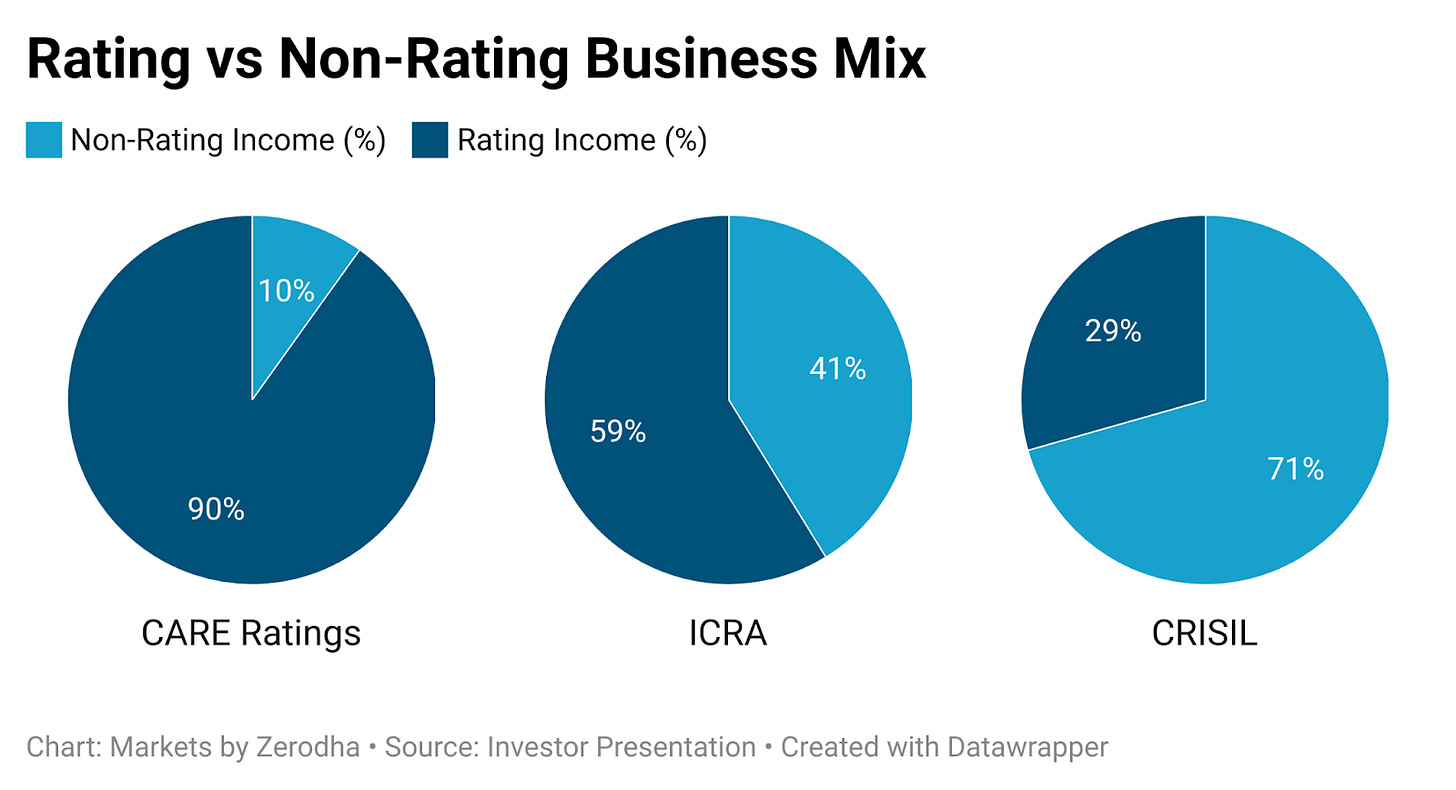

A CRA’s business mix, then, is a matter of what trade-offs it will accept. CRISIL, for instance, sees 70% of its business come outside ratings.

While this makes their business less cyclical, it also means they have the lowest margins in the industry.

How do they run their business?

Who pays for ratings? It’s not the lender or investor who actually uses ratings. It’s the borrower that pays to be rated. Companies that are looking for outside money approach a CRA, have them analyse their business, and assign a rating.

There are practical reasons for this.

For one, a good rating can eventually reduce borrowing costs, saving you money. If a rating agency gives you a high grade, for instance, investors that know nothing about your business see you as low risk, and will accept a lower interest rate on your bonds. This is especially important if you’re a first-time issuer or not a household name.

Second, ratings are often compulsory, whether due to regulation, or the internal policies of major lenders. Mutual funds, banks, pension funds, and insurance companies often can only invest in bonds above a certain rating. If you don’t have a rating, these won’t even consider your debt.

Essentially, while giving out money, lenders are perennially afraid that they might be duped. CRAs give a signal that they’re safe. Hence, issuers are willing to shell out money for that signal. Naturally, this also creates conflicts of interest. We’ll get there shortly.

CRAs basically have two key revenue streams.

First, Transaction-based fees

Whenever a company or government comes to the market with a fresh bond or loan that needs a rating, the CRA charges an initial fee. This revenue is transactional. It depends on the flow of new deals, making it dependent on market cycles. When markets are flush with money and lots of companies are borrowing, fees gush in. But when capital markets hit a dry spell, new borrowers disappear — and this revenue dries up.

Second, Recurring fees

Once an initial rating is given, borrowers pay a recurring annual fee for the agency to monitor and maintain that rating. These surveillance fees are usually much smaller than the initial fee, but they repeat every year until the debt matures or is paid off (or in the rare case a borrower decides to switch). This creates a small but steady stream of revenue.

Meanwhile, CRAs’ non-rating services, too, usually generate steady, recurring revenue too — for example, they might sell subscriptions to their research, or annual contracts for risk assessment tools — all of which bring in recurring revenues.

The mix matters

The overall business model of a rating agency, then, depends on their specific mix of these revenue streams. A business that depends on one-off ratings has better, but more uncertain, margins. Those that rely on recurring or non-ratings businesses get stability, at the cost of low margins.

Either way, though, this is a solid business — a knowledge-driven, asset-light business with fantastic economics. CRAs run on people, methodologies and data. They only spend on salaries, offices, and the maintenance of their information databases and technology. They don’t need factories, heavy machinery, or capital investments. This gives them very high margins (30%+) compared to traditional businesses.

Growing this business, too, doesn’t require capital expenditure — you just need more talent, and more deals. As a result, these companies often have strong cash flows, and pay out much of their earnings as dividends. For example, CARE Ratings has historically paid out around half its profits as dividends.

Trust: the real currency of ratings

There’s a problem at the heart of this business, though. After all, rating agencies are supposed to give unbiased opinions — but are paid by the entity they judge. Occasionally, these conflicts become glaringly apparent, as they did in the 2008 financial crisis, when instruments that American rating agencies called investment-grade turned out to be hollow.

This has happened in India as well. In 2019, for instance, DHFL (Dewan Housing Finance Ltd.) defaulted on its debt, shocking everyone. Just three months before, CARE Ratings had graded some of its debt as AAA — indicating that the company was spotless. CARE’s reputation took a bad hit for failing to flag the risk early, making issuers and investors wary of engaging them.

This illustrates a brutal truth: trust, once lost, is hard to regain in this industry.

This is critical, because the entire business runs on trust and reputation. In fact, the real product they’re selling is credibility, not the rating itself. Anyone could give a rating. Investors only trust the rating if the agency appears competent and honest in its evaluation. If that faith is shaken, their opinion becomes meaningless.

A license, alone, can’t buy this trust. This is why, despite there being seven SEBI-registered rating agencies in India, the industry is dominated by an oligopoly of three players — CRISIL, ICRA, and CARE — who together command ~95% of the market. This concentration is reinforced by the fact that it’s only mandatory to get rated by any one agency only. Anyone outside the big three, then, must essentially fight them off for business — an uphill battle.

There are perception differences among the big three as well.

Crisil, for instance, partly owned by S&P Global, is often regarded as the gold standard. Its ratings are seen as more conservative and credible, which means a Crisil AAA might carry a bit more weight with investors than an equivalent rating from a smaller agency. This prestige allows Crisil to charge a premium for its services.

ICRA (linked to Moody’s) and CARE Ratings are also respected, but Crisil’s rating processes and scale give it an edge in reputation. This isn’t something you’re likely to see in an official report, but it’s common market chatter. And reputational edge is everything — it’s why the top three keep the top three spots and the others fight over scraps.

From the issuer’s perspective, the choice of rater often comes down to trust vs. cost.

If a company is planning to raise money from the public or from discerning global investors, it will likely lean toward a rating from a reputed agency, even if it costs more. For example, an Indian company might insist on a Crisil rating because overseas investors look up to them. On the other hand, if a company already has a few banks or private investors lined up and just needs a mandatory rating for formality, it might shop around for a cost-efficient deal. This dynamic leads to the “rating shopping” phenomenon – firms hunting not just for a good rating, but for the agency that will give it to them with the least hassle.

Another factor reinforcing the dominance of the big players is inertia and switching costs. Once a borrower has an existing rating from, say, ICRA, they have an established relationship and the agency already knows their business inside-out. If the borrower wanted to switch to another agency, it means going through the hassle of the analysis process afresh with someone new, paying a fresh fee, and probably even getting a different outcome. Unless they’re really unhappy with their current agency, most issuers stick with their current CRA for updates and new borrowings.

The bottom line

When you think about it, credit agencies don’t need a lot of things to do their business — just honesty and skilled talent. With that, they generate large amounts of cash. Their asset-light model also means most of what they earn eventually finds its way back to shareholders.

Their growth engine is equally straightforward: credit growth. The more borrowing an economy does, the more ratings get issued, monitored, and renewed. And historically, credit growth has a habit of outpacing GDP growth. So if India compounds at 7%, credit could easily compound at 10–11%, and the rating businesses that sit on top of this cycle can ride along.

But, with great power comes great responsibility. Their product, revenue and margins are all reflective of a single trait: trust. In the long run, that’s the biggest factor that can make — or break — their business.

Tidbits

JSW Steel shifts Bhushan Power unit into JV with JFE

JSW Steel will move Bhushan Power & Steel’s business into a 50:50 JV with Japan’s JFE Steel for ₹24,483 crore ($2.72 bn) to fund expansion. JFE will invest ₹15,750 crore in phases, with the JV targeting 10 MTPA crude steel capacity by 2030. The move follows the Supreme Court’s recent approval of JSW’s takeover.

Source: Reuters

India’s iron ore imports hit six-year high; JSW top buyer

India imported over 10 million tonnes of iron ore in Jan–Oct, more than double last year, due to shortages of high-grade ore and cheaper overseas prices. JSW Steel was the largest buyer, aided by proximity of its Maharashtra plant to ports. Imports are expected to reach 11–12 million tonnes in FY26 if domestic supply doesn’t improve.

Source: Reuters

Ola Consumer pauses food and grocery services

Ola has quietly suspended its food and grocery offerings, including cloud kitchens and ONDC-based deliveries, as it restructures its non-core portfolio. The company has fallen to third place in mobility (behind Uber and Rapido) and is now refocusing on core ride-hailing profitability after past retreats from Ola Cars and Ola Dash.

Source: BusinessLine

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

curious to as where CIBIL comes in these CRAs? or are they another category?