Indian pharma wants to conquer cancer

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Storming the castle of the emperor of all maladies

RBI pulls the plug on Simpl

Storming the castle of the emperor of all maladies

Cancer is a soul-crushing disease. Testing positive for it is practically a death sentence — an announcement that you might not have long to live.

The pain doesn’t merely lie in the knowledge that you have cancer — it’s in what cancer patients must live through. The treatment can be as harrowing as the disease. You have to go through many rounds of chemotherapy, which tears your life apart. You’re constantly tired and nauseous, your hair falls out in clumps, your mouth is covered in sores, you can’t imagine eating. It is a living hell.

In each round, you spend ~₹20,000 — with the best hospitals charging closer to ₹50,000. A surgery can set you back even further, costing lakhs. And post-chemotherapy drugs — the medicines meant to manage the terrible side effects of your cancer treatment — cost you tens of thousands more. The average Indian can hardly afford any of this.

All this can amount to nought. The treatments don’t always work. Cancer survival rates in India are poor. Often, all they do is delay the inevitable.

Cancer has been described as the emperor of all maladies — the greatest disease we have ever had the misfortune of dealing with. It has been considered unconquerable throughout history. It wrecks its way through lakhs of Indians every year, most of whom can’t even afford the treatment.

But there might be an unexpected ray of hope. India’s pharma industry, today, thinks it can finally overcome the disease. Firms like Biocon, Dr. Reddy’s and Glenmark are all betting on oncology drugs as the next big thing. To learn about the recent advances of this industry, to us, has been nothing short of magical. That’s what we wanted to share with you.

In this primer, we’ll look at the landmark drugs that so many companies have announced in this space. Some day, we shall cover the other defences we’re evolving to beat this disease.

A brief history of cancer treatment

Human cells constantly split up and multiply.

This is happening in your body at this very moment. Your body is making millions of new blood cells right this moment. Your skin cells are multiplying rapidly, as old ones fall off. The cells of your stomach are constantly re-creating themselves. And so on.

However, sometimes, a switch in the genetic code of your cells suddenly flips. It starts multiplying rapidly, and abnormally. Some part of that growth breaks away, and spreads out — growing rapidly wherever it lands. It has become a cancer.

When this could happen is hard to predict. Even a healthy person can suddenly get cancer.

Cancer cells, moreover, can also be stealthy. They might create a protein called PD-L1 — programmed death-ligand 1 — which smothers your immune cells, and fools your body into thinking everything is normal. These cells practically act as deadly double agents, amassing secret armies that overwhelm your body from the inside.

To tackle all this, we came up with chemotherapy. Chemotherapy drugs are, functionally, a kind of poison that attacks the very process of cell division — whether in a cancerous cell or not. In effect, it carpet bombs all parts of your body that are growing quickly. They kill cancer cells, but also kill the cells in your hair follicles, your gut, your bone marrow and more. Normal bodily functions — like hair growth or gut renewal — are ruined in the process. That is why chemotherapy leaves behind so many side effects.

The biologics revolution

Recently, there’s been a revolution — cancer treatments have shifted towards biologics. These are complex medicines created in living cells — such as bacteria or the cell lines of other mammals. With that complexity, we gain the power to use them for more specific tasks.

You already know some biologics. Insulin, for instance, which is used for diabetes, is a biologic that only targets specific insulin-sensitive tissues.

Cancer biologics, similarly, can be a lot more targeted than classic chemotherapy drugs. Instead of attacking cell division everywhere in your body, they’re designed to recognize specific targets on cancer cells, or to modulate the immune system.

There are three main biologics for cancer:

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): Imagine mAbs as well-trained bloodhounds that can sniff out specific cancer cell markers, and then block their growth signals, or flag them for destruction by the immune system. Trastuzumab, for instance, specifically targets HER2+ breast cancer cells.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs): These are antibodies that go and attach themselves for substances like PD-L1, opening them for attacks by the immune system. Keytruda, currently the world’s best selling drug of any kind, is one such ICI.

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs): ADCs, a fairly new concept, are antibodies with a small amount of chemotherapy drug attached. They hunt for cancerous cells and specifically deliver their payload there, sparing the rest of the body. For instance, in HER2+ breast cancer, ADCs have shown significantly better results than the antibody alone.

Hard to understand, harder to master

While biologics show a lot of promise, they’re extremely hard to manufacture. Classical chemotherapy drugs, in comparison, are far simpler.

This boils down to the composition of biologics. You can’t whip them up in a chemistry lab; you need to create them in living cells that need extremely specific conditions. For that, you need specific bioreactors that can mass-produce the cell you want. Then, you’ll need another set of machines to extract the protein from those cells that will make your medicines. And finally, you’ll have to prepare them for (cold) storage and transport.

Meanwhile, the mildest swings in temperature or nutrient levels can ruin a batch worth millions of these cells.

Putting this entire process together takes tremendous amounts of capital.

Because of the sheer complexity of biologics, they also need a lot of testing. Regulatory trials for biologics can take extremely long — with good reason. When they work well, these are extremely capable tools. But by the same token, if they misfire, that could mean the difference between life and death. Almost 70% of the total expenditure in developing these drugs comes up in these trials. Over 90% of oncology drugs fail.

This is why Western pharma firms that did crack biologics wanted those successes to pay off for all their failures. So, they protected them jealously with patents. But, much like diamonds, patents don’t last forever. These blockbuster biologics began losing protection around 2014-2020.

And the Indian pharma industry saw a business opportunity.

The pharmacy of the world arrives

India’s pharma industry has made an entire business around making medicines cheaper than ever. Our exports of “generic” versions of many medicines earned us the moniker of being the “pharmacy of the world”.

But we didn’t stop at generics. Indian pharma has been using their profits from those sales to move up the value chain and make original formulations. We wanted to be an innovator. As major biologics patents expired, Indian pharma firms saw an opportunity in biosimilars — which are highly-similar versions of biologics.

Unlike simpler generics, biosimilars aren’t just off-brand versions of biologics. The original drugs were made inside living cells, and there are no simple chemical processes Indian companies could copy. The original manufacturers of a drug don’t even reveal what cells they used. And so, Indian pharma companies have to re-discover how to make these drugs, from scratch — while also being highly similar to the original, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. They must practically re-invent the wheel.

This complexity also means they have to be tested rigorously to show they’re as effective as the original.

But for all that complexity, as those patents expired, biosimilars did bring down prices considerably. Biosimilars are usually 30-60% cheaper than biologics. Take a 440 mg vial of Trastuzumab: its price dropped from a range of ₹55,000-75,000 to ₹18,000-30,000 because of the entry of Indian biosimilars. Still costly, yes, but it made the drug affordable for a huge chunk of India.

Betting on cancer

Recently, various Indian pharma firms have highlighted how big they think the oncology market is, both in exports and domestically. They’re pouring tons of risk capital into making biosimilars.

That conviction shows in their quarterly earnings calls.

Glenmark, for instance, has been aggressively expanding its oncology portfolio. It just made one of the boldest moves of the space last week: a $1.1 billion licensing deal with Chinese firm Hengrui for a novel ADC:

Similarly, Biocon’s biosimilars for trastuzumab (Ogivri) and pegfilgrastim (Fulphila) maintain a robust 27% market share in the US. And, despite competition heating up in the space, they’re launching more cancer drugs.

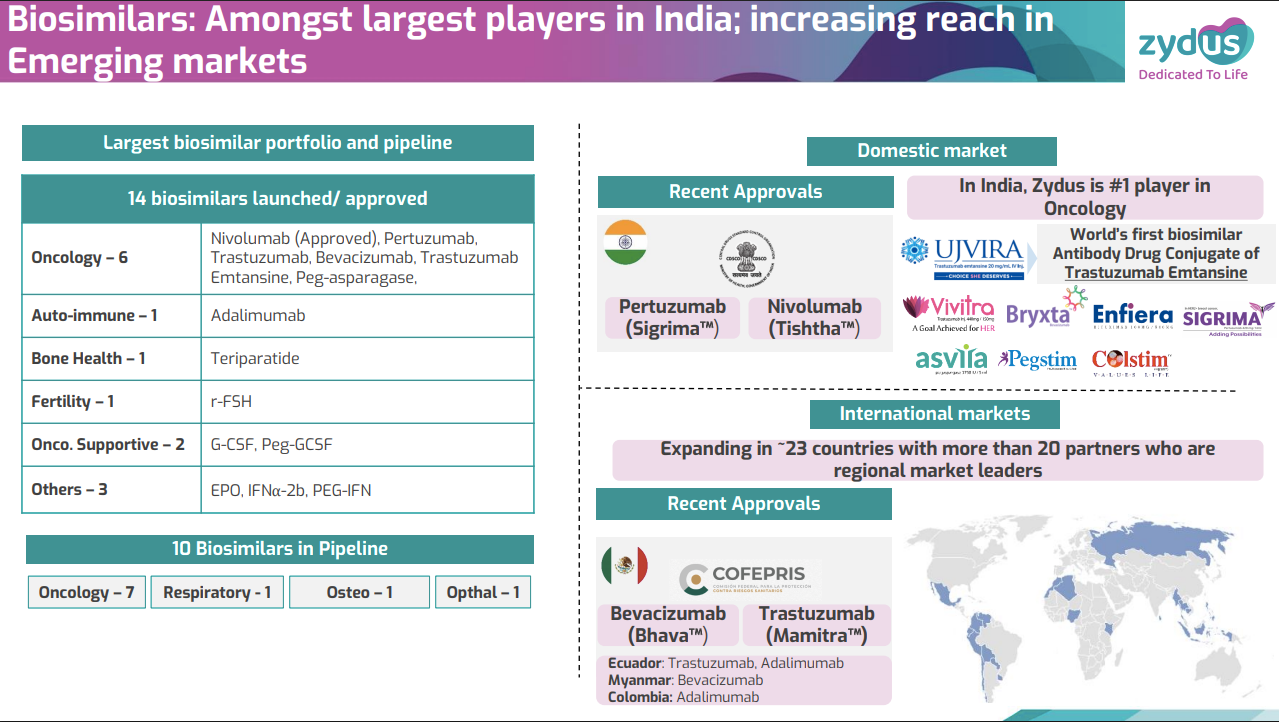

Zydus, meanwhile, claims to be the biggest domestic player in oncology. In 2021, they launched Ujvira — the world’s first biosimilar ADC — far below the original’s price. Of their entire present (and future) pipeline of biosimilars, oncology leads the pack by a mile.

We’re seeing a couple of trends emerge from this activity.

For one, at the moment, many of these drugs are mAbs. More advanced formulations like ADCs are more complex — on top of making an antibody, they require you to combine a chemo molecule, which adds a new layer of complexity. These mAbs are generally for breast, lung, and rectal cancer. ICIs, while relatively newer, are also catching pace.

Second, Indian pharma firms are getting into many joint ventures for oncology drugs — especially with Chinese firms. Besides the recent Hengrui deal, for instance, Glenmark is also working with China-based Beigene for ICIs. Dr Reddy’s, meanwhile, licensed an ICI called Toripalimab from the Chinese firm Junshi. China’s biotech industry, as we’ve covered before, is much ahead of ours — but we’re now leaning on them for know-how.

The bottlenecks

Despite all of this deeply impressive progress, India faces massive hurdles in its oncology ambitions. We’ll cover three of the biggest ones.

The biggest problem is our lack of trial infrastructure. India accounts for 8% of the global cancer burden, but conducts only 2% of global oncology trials. On top of the massive costs these trials add to the process, we simply lack the infrastructure for it — and fall behind Western standards. Without a more robust trial infrastructure, we’ll largely be limited to licensing biosimilars, which puts us behind the cutting edge.

Our weak trial infrastructure leads to a second problem — there are big quality concerns around Indian biosimilars. Early Indian biosimilars were approved with less stringent data than Western regulators required, leading to initial skepticism among oncologists. In fact, a recent study by global pharmacists found that 20% of Indian cancer generics failed important quality tests (although these weren’t biosimilars) — possibly because companies try to avoid price increases due to trials. News like this dents the reputation of Indian medicines, maybe even hampering our progress in biologics.

Lastly, our intellectual property law for biologics remains weak. Historically, we have been reluctant with protecting medical patents, which has helped our generics industry flourish, But as we climb the innovation ladder, those very choices are stifling our ability to make high-risk R&D bets. Our patent laws previously protected a company like Zydus, when Roche tried to block one of Zydus’ biosimilars. But if Zydus tries to make its original formulations, it could soon find itself in the same position as Roche, making those same patent laws difficult to navigate itself.

Down with the king

For all this, we are making impressive progress. Cancer may be “the emperor of all maladies”, but India wants to overthrow the emperor, and the stars are aligning for that to happen. As the patents of key biologics expire, our firms have achieved the technological capacity needed to take on the tough task of replicating them. We know what needs to be done, and our market is already zooming in.

There are still real hurdles to genuine innovation. Even as we were writing this, for instance, the US announced 100% tariffs on branded drugs. That is, in essence, a tax on innovation.

But this is a deeply important project. If India succeeds, it won’t just mean a more competitive domestic pharma industry. It’ll mean millions of lives — especially in poorer countries that can’t afford good healthcare — will be saved from the greatest and most terrible of all diseases.

RBI pulls the plug on Simpl

Last week, RBI sent a blunt letter to Simpl, the checkout pay-later startup, ordering it to immediately stop all payment operations—be it payment, clearing, or settlement. Now, at the time of writing this, there was no official communication from the RBI. But the letter has been confirmed.

Why did RBI take such a drastic step, virtually shutting down a payments business overnight?

Because the RBI believes that Simpl has been running a payment system without authorisation under the Payment and Settlements Systems (PSS) Act. In simpler terms, they are accusing Simpl of acting like a licensed payments company without, well, a license. Coincidentally (or not), this crackdown comes right after RBI rolled out the new Payment Aggregator rules, tightening the screws on every business that even touches the flow of money.

This isn’t the first time BNPL startups are getting under the scrutiny of regulators, though. They have had their fair share of tussles back in 2022, but we’ll get to that.

Let’s start with Simpl(e) things first.

What Simpl actually does

Simpl’s core idea wasn’t too complicated: let users shop now and worry about the payment later. Instead of entering card details or punching UPI pins for every small order, you’d just hit “Pay with Simpl”. In the backend, Simpl would either give you a single consolidated bill 2 weeks later with zero interest on your credit payments, or allow you to break a large order into three equal parts — called the Pay-in-3 model.

Simpl wanted its business to look like a typical khata system at any kirana store. If you’re a regular customer of your local kirana store, for instance, you’d have often bought things on small amounts of interest-free credit which you’d pay back later. The kirana store owner would log this in his khata. Simpl just wanted to translate that convenience into the digital realm, while also including bigger businesses.

On the other side, for merchants, Simpl promised fewer drop-offs at checkout. Cart abandonment issues at checkout are a huge problem for digital businesses. According to some estimates, as high as 70% of all carts on the desktop are abandoned.

Now that can happen for a whole host of reasons, but making sure of a smoother payment experience at least, makes life a bit easier for merchants. Simpl removed interruptions from entering OTPs or UPI PINs, which meant more completed transactions, and therefore higher sales. By its own claims, Simpl was live on 26,000+ merchants — names like Zomato, BigBasket, and Rapido.

But these numbers are less important than the image Simpl presented for itself: it called itself a “payments utility,” not a lender. That’s an important point to remember for the later half of the story.

Other BNPL players, however, were positioning themselves very differently. BNPL startups often let money flow through wallets (called PPIs) or their own pool accounts. Either way, BNPL startups acted as a lender, and the RBI didn’t like it. They were doing all these lending activities without a (NBFC) license.

So, to crack down on that, the RBI came out with two big rules:

Digital Lending Guidelines (Sept 2022): If you’re doing credit, the money must come directly from a bank (or NBFC) to the merchant, and repayments must flow directly back. No fintech should sit in the middle of that transaction.

PPI clamp (June 2022): Fintech companies often dressed up their wallets as credit cards. So, the RBI said, no more loading wallets of fintech apps with loans.

The RBI’s left a clear message: “If you touch money anywhere, you need the licence that matches the function of either lending or payments.” That left companies with two clear lanes: they could either be a licensed lender themselves (NBFC), or be a licensed payment aggregator.

So, what lane would Simpl pick? Since it didn’t extend loans on its own balance sheet, it didn’t go for an NBFC license. But, it still touched the settlement flow. And in RBI’s eyes, once you’re handling collection and settlement, you’re not just a khata. You’re a payment system and that needs a license.

Unfortunately, for a “payment utility” like Simpl, it also failed RBI’s payment aggregator (PA) rules.

The licence test Simpl failed

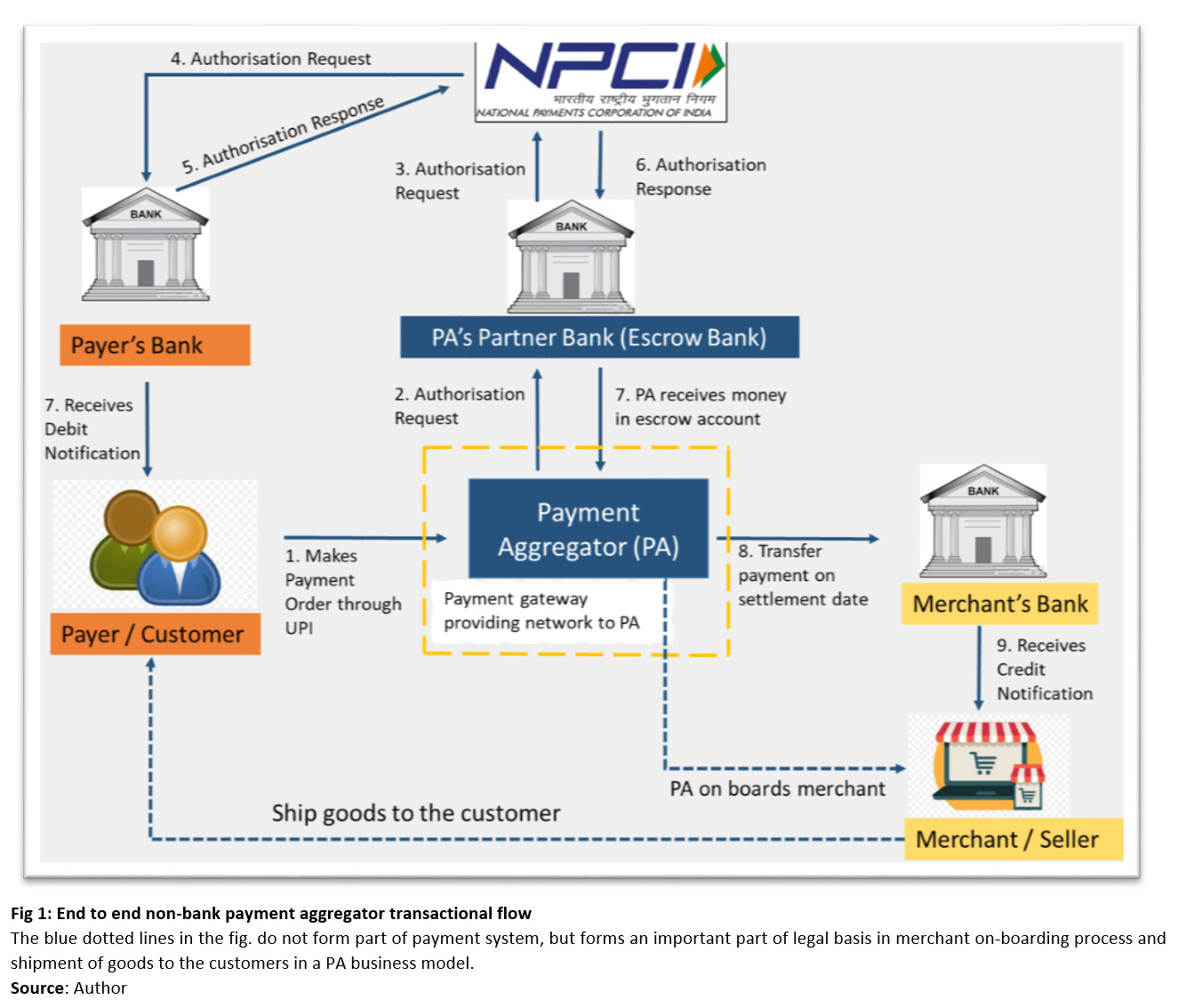

Now, what does a PA do? Think of it as the boring but essential middleman of digital payments. They fulfil three functions:

Onboard merchants (do the KYC, check legitimacy).

Collect money from customers into a tightly ring-fenced escrow account with a bank.

Settle that money to merchants within RBI’s mandated timelines — usually same day or next day

It’s unglamorous plumbing work, but it definitely matters. Having an escrow mechanism ensures that fintech can’t casually dip into merchant funds and use it for other riskier purposes. Quick settlement timelines mean merchants get their dues fast. And proper merchant checks stop shady operators from using the payments ecosystem to launder money.

In short: this is how RBI keeps the payments system safe from turning into a shadow banking free-for-all, while keeping merchants and consumers protected.

Now, let’s put Simpl through the PA checklist.

RBI’s letter accused Simpl of “performing payment, clearing, and settlement functions without authorisation under the PSS Act.” That is the official definition of being a PA. If Simpl, or anyone acting on its behalf, was collecting money from customers and paying out to merchants, then functionally it was operating as a PA. And you simply cannot do that without RBI’s licence.

Simpl’s defence to that has long been that they’re just a ledger or digital khata that doesn’t lend or issue wallets. But RBI saw their function as that of a PA and not a mere ledger. It’s as if, in an office building, you installed pipes that did not have BIS certification. Except, Simpl’s non-certified pipes move money.

The fallout and the lessons

Here’s where Simpl’s at with this RBI move. It doesn’t have too many ways forward, and the ones that exist aren’t easy. And if it can’t take to any of these options, it may have no choice but to shut shop altogether.

One possible option is to piggyback on an already-licensed Payment Aggregator. In practice, this would mean Simpl stops handling collections itself and instead routes every rupee through an escrow account owned and monitored by a licensed partner. Simpl would then reposition itself as a pure UX layer — still present at checkout, still reminding customers to pay, but without control of the money flows. That would keep it alive, but it also shrinks the margins and influence it once enjoyed.

The second path is more ambitious but also more punishing: apply for its own PA licence. On paper, this would solve the regulatory problem at its root. But getting there is neither fast nor cheap. RBI has set high capital requirements, tight escrow rules, and ongoing compliance obligations. Simpl, a venture-funded BNPL startup, would suddenly be competing with deep-pocketed payments giants who already play in this league. That’s a long, uphill climb.

A third option is to pivot fully into being a Loan Service Provider. In that setup, Simpl would only provide the tech and UX front-end, while an NBFC or a bank provides the credit and directly handles cash flows. That is compliant, but much like the first option, it would reduce Simpl to being a simple service layer that’s dependent on a regulated partner. Maybe, even the “khata” branding and the business economics would look quite different.

This isn’t just about one startup. RBI is making its perimeter clear: if you resemble a Payment Aggregator, you need PA-grade compliance. If you resemble a lender, keep a bank or NBFC in the driver’s seat. And above all, your partner’s licence is not your licence. The regulator looks at who actually touches the money.

RBI’s moves don’t mean that India is anti-innovation. But it is anti-shadow payments, and does not have an appetite for fintechs that move money without the right licence. The winners in this next chapter won’t be the slickest checkout apps or the quirkiest khata pitches. They’ll likely be the ones who design for licence-correct fund flows before anything else.

Tidbits:

US plans 1:1 chip rule

The US is considering a rule requiring chipmakers to produce domestically as many chips as they import, or face tariffs. The aim is to cut reliance on overseas suppliers and boost economic security. Companies pledging to build US plants could get temporary tariff relief, spurring big investments in local manufacturing.

Source: ReutersRussia restricts fuel exports

Russia will ban diesel exports by resellers and extend gasoline export restrictions until year-end after Ukrainian drone strikes cut refinery output. The move aims to ease domestic shortages as refining capacity fell sharply. Producers can still export via pipelines, which account for most diesel shipments.

Source: ReutersIndia inks $7 bn Tejas deal

India signed a ₹623.7 billion ($7.03 bn) deal to buy 97 homegrown Tejas Mk-1A fighter jets from Hindustan Aeronautics. Deliveries will span six years starting FY27-28, boosting the Air Force as MiG-21s retire. Officials also plan a follow-on order with GE for engines.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉