Indian Banking in 2025: the year in review

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads-up before we dive in. The Bharat Coking Coal IPO is open now. We wrote about them earlier — you can read the full story here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Unpacking India’s Banking 2025

When Indians expect prices to fall, what happens to their portfolios?

Unpacking India’s Banking 2025

Banks are one of the biggest moving parts of the Indian economy. And the funny thing is if you want a quick snapshot of what’s going on inside them, you’ll never run out of data.

So as we step into 2026, it feels only fair to do a proper year-end wrap of banking and financial institutions. And for that, we’re leaning on the RBI’s freshest set of cues: its Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India and the Financial Stability Report, both released over the last few weeks.

The plan is simple. No heavy jargon. Just a clean story with a few charts, a handful of numbers, and the bigger narratives we could piece together from what the RBI was telling us.

Low NPAs, but with an Asterisk

Let’s start with the headline everyone loves.

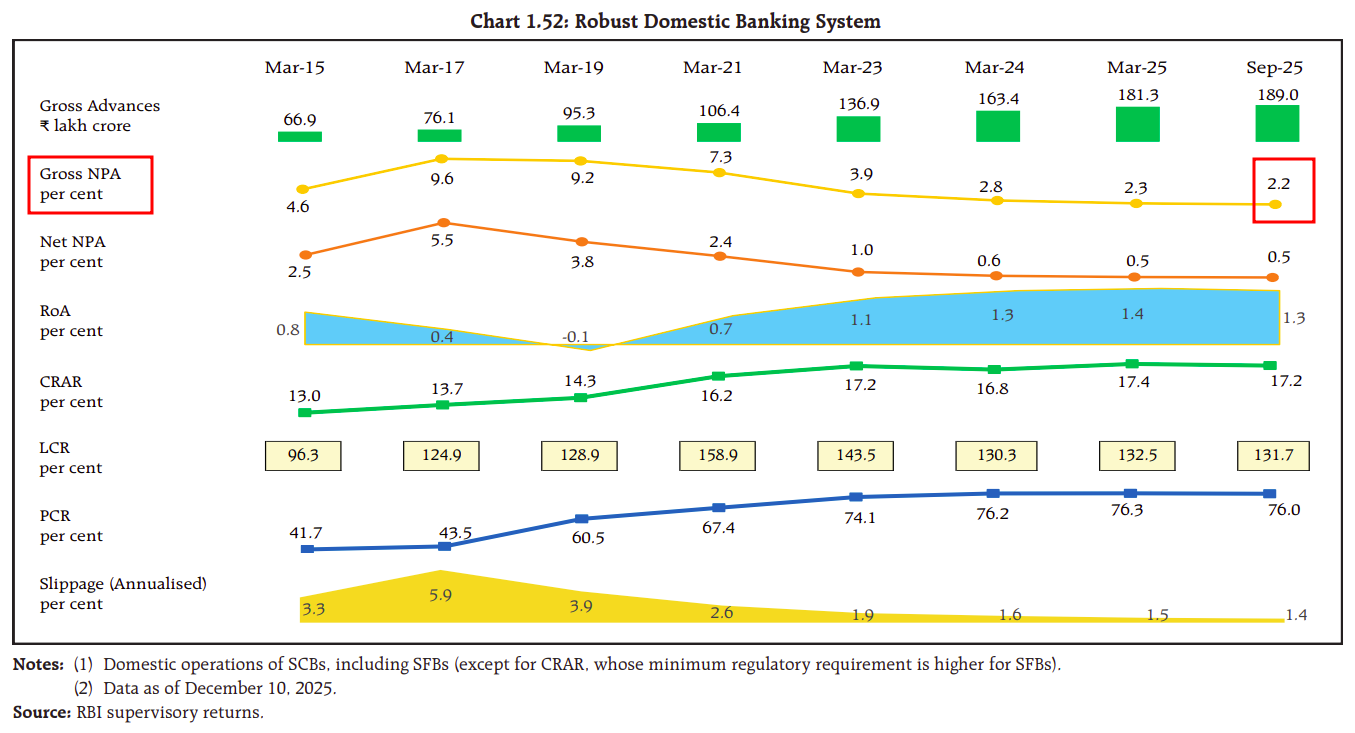

Bad loans are at a multi-decade low. Gross NPAs are down to 2.2% of total advances. That’s an insanely clean number for Indian banking. And honestly, if you’ve been following banking (or reading The Daily Brief), you’ve seen this trend build year after year. Every year, NPAs seem to hit a new low.

But it’s worth pausing here, because there are two ways to get to a low NPA ratio. One is straightforward: you stop making bad loans. The other is less talked about: you get quicker at clearing old bad loans off your balance sheet. Indian banks have done both, but the second part has played a larger role than the headlines suggest.

Here’s what that looks like in numbers. In FY 2024–25, banks added about ₹2.26 lakh crore of fresh NPAs. But the overall stock of NPAs still fell by about ₹2.75 lakh crore. That gap exists because banks cleaned up the book through multiple channels and the biggest one by far was write-offs. Banks wrote off around ₹1.58 lakh crore in FY25. Actual recoveries were roughly ₹0.68 lakh crore.

None of this is wrongdoing. Write-offs are a legitimate tool — banks accept the loss, take the hit, and move on. But it changes what the “2.1% GNPA” headline really means. A low NPA ratio is not only about better repayment behaviour. It is also about how aggressively banks are pushing legacy stress out of the system, and how fast the loan book is growing in the background, which makes the ratio look even better.

The same nuance shows up in insolvency recoveries too. Under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), many large cases have been resolved, but often after deep haircuts. As of September 2025, creditors had resolved cases with ₹12.3 lakh crore of admitted claims, but realised only ₹3.99 lakh crore — roughly a 32% recovery, implying a 68% haircut. That is still better than dragging cases endlessly, but it is not the same as “banks got their money back.”

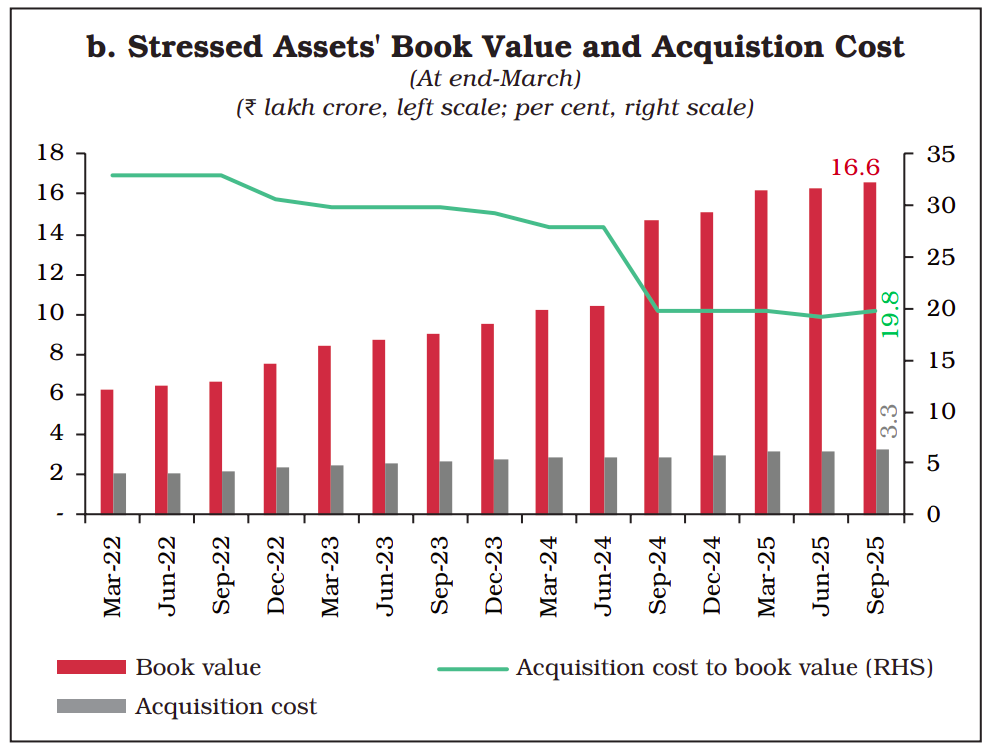

Another quiet piece of this cleanup story is banks selling stressed loans to Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs). ARCs buy bad-loan portfolios from banks at a discount, and then try to earn a return by recovering more than what they paid. It’s a standard mechanism — but what’s interesting is what the RBI’s data is showing now: banks are selling more stressed assets, and they’re getting paid less for them.

This again doesn’t mean anything shady is happening. It just reinforces the broader point: a chunk of the “clean balance sheet” story is coming from banks choosing to exit bad loans faster, even if it means taking a hit and accepting a lower price, because the priority is to get these loans off the books.

Fintech frenzy

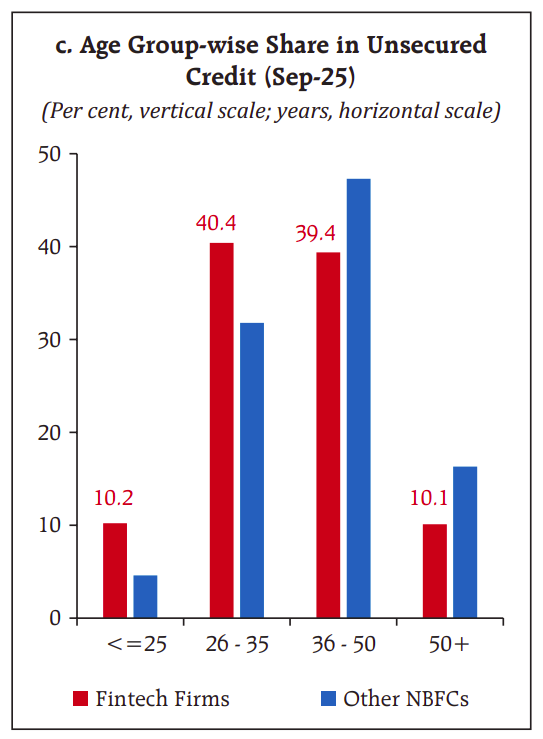

App-based loan companies, digital NBFCs, and peer-to-peer platforms have exploded onto the scene. The allure is obvious: using alternative data and slick user interfaces, fintechs can onboard borrowers quickly, often younger customers who might not have a long credit history. The majority of these fintech loans (over 70%) are unsecured – essentially digital personal loans or credit lines – and more than half are going to borrowers under 35.

But the RBI’s Financial Stability Report is also quietly waving a flag here.

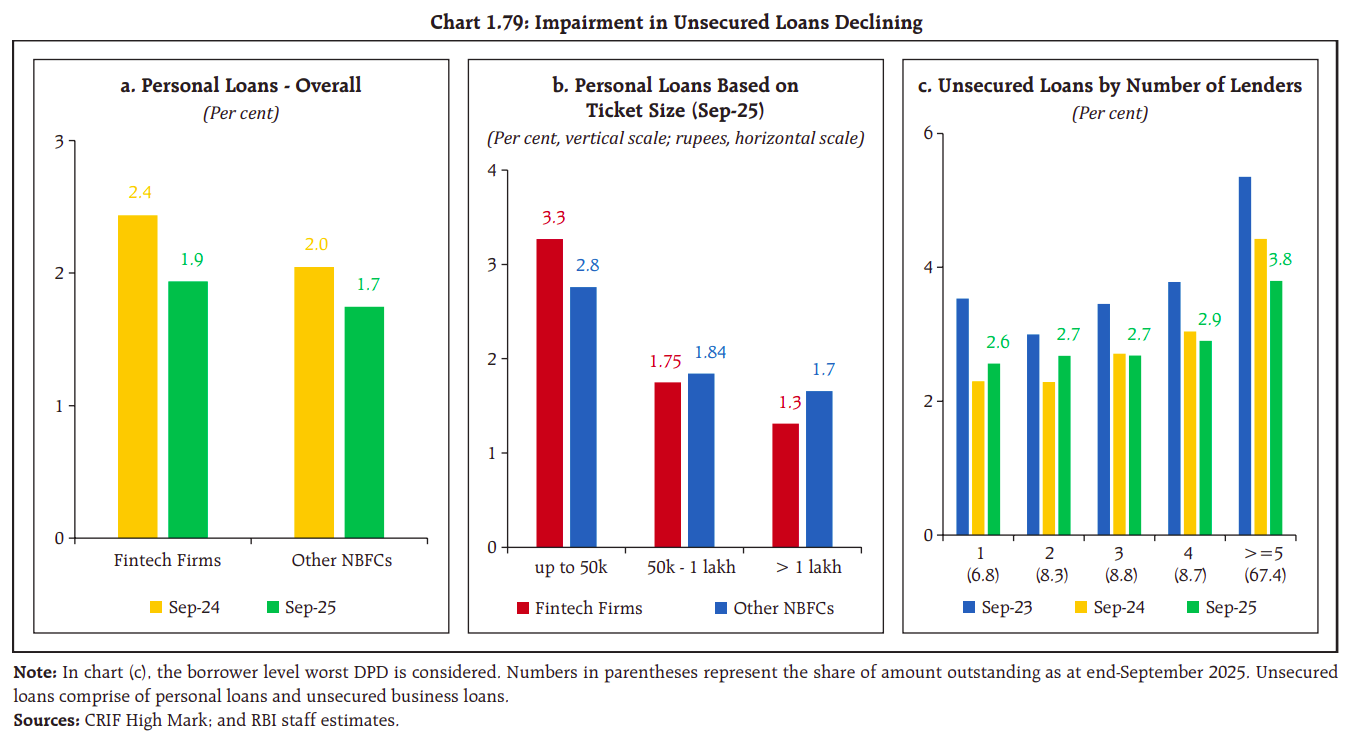

It points out that personal loans originated by fintechs have seen higher impairment losses than the broader NBFC universe. More tellingly, it highlights a specific stress pattern: borrowers who have taken loans from five or more different lenders show significantly higher impairment (default) rates. That’s usually what “credit saturation” looks like in real life — not one big loan going bad, but lots of small loans stacked on top of each other, across multiple apps, until repayment simply breaks.

And this isn’t hard to explain. It’s structural. Fintech lending is heavily skewed toward unsecured products, often with less depth of information than a bank would typically demand. A bank underwriting a home loan has collateral, income documents, long repayment history, and time. A digital lender might approve a ₹50,000 loan to a first-time borrower based on a PAN card and some digital signals. That speed is great for access. It’s also fragile if the borrower’s income takes a hit — or if they borrow again and again from other apps.

And no, this risk doesn’t stay neatly inside fintech. In many cases, it loops right back into the banking system. A lot of fintech lending is ultimately funded by banks or done through partnerships — via credit lines, co-lending arrangements, or banks buying out loan pools. So if defaults rise in fintech-originated books, the pain doesn’t remain a fintech problem for long. It eventually shows up on mainstream balance sheets.

The NBFC partnerships

Another piece of the puzzle is the intricate dance between banks and non-bank financial companies (NBFCs).

NBFCs often originate loans that banks then buy (direct assignment), co-lend on, or fund indirectly. In theory, it’s a win-win. NBFCs can reach customers and geographies that large banks don’t, and banks can scale up lending quickly without building the entire distribution network themselves. Banks also get an easier route to retail growth and priority-sector exposure, while NBFCs get access to cheaper funding and a larger balance sheet partner.

But the RBI’s Financial Stability Report offers a useful reality check: moving risk around doesn’t remove it. It can actually make it harder to see — and in some cases, more concentrated.

The data is eye-opening. Banks have been increasingly leaning on NBFC-originated assets to pad their loan books, and about 80% of these acquired loans come from just a handful of big NBFC players.

If even one of those large NBFC partners hits trouble, the shockwaves would reverberate through multiple banks that had been feeding off its pipeline. The RBI bluntly calls this out as a concentration risk: banks might think they’re diversifying by buying loans instead of lending directly, but if they’re all buying from the same few NBFCs, they’re effectively placing the same bet.

There’s also the question of asset quality in these partnered loans. Interestingly, the FSR notes a divergence: private banks have generally bought higher-quality pools (their acquired loans perform better, even better than those NBFCs’ own books in some cases), whereas public sector banks have chased yield and volume to their detriment. For PSBs, the loans they acquired via direct assignments or co-lending have seen higher loan losses than the ones the PSBs originated themselves

As of Sep 2025, public banks’ co-lending NPAs were around 5.7% (not low at all, though improving), compared to just ~2% for private banks’ co-lending books.

All these threads tie back to a common theme: risk hasn’t disappeared, it’s just shifting locations. Banks and NBFCs are now tightly interlinked: banks lend to NBFCs and buy NBFC loans, NBFCs depend on bank funding and promise banks easy growth. It’s a symbiotic loop, which works great – until it doesn’t.

The Deposit Squeeze

So far, we’ve stayed on the asset side — loans, credit growth, and how clean (or not-so-clean) those books really are. But banks don’t run on loans. They run on funding. And that’s where 2025 throws up another quiet contradiction: credit has been booming, but deposits have been harder to gather.

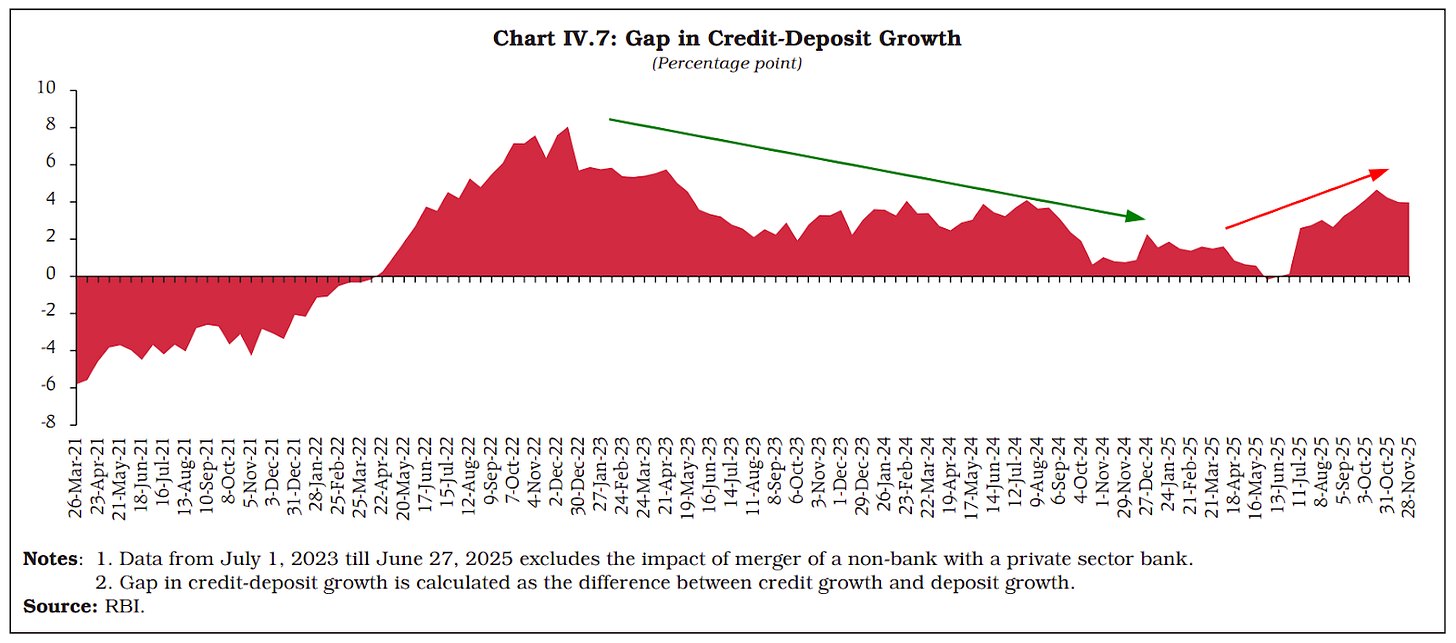

Through the second half of 2025, banks slipped back into a familiar race — competing aggressively for household savings. Loan growth kept running ahead of deposit growth, and that creates a simple problem: a funding gap. Banks can manage it for a while through market borrowings, CDs, or short-term money. But structurally, if deposits don’t keep up, the system starts to feel tighter.

What’s interesting is that this pressure had eased after the 2022 peak, when lending was exploding and CD ratios were getting stretched. For a bit, things cooled off and funding stress looked manageable again. But by late 2025, the heat started returning.

Why should we care? Two reasons: profitability and stability.

On profits, the story is simple. People are keeping less money parked in low-interest bank accounts. They’re moving it into anything that pays better. So banks have to fight harder for deposits, and that usually means one thing: higher deposit rates. The moment banks start paying more to raise money, their cost of funds goes up. And when funding gets expensive, net interest margins get squeezed — because the spread between what banks earn on loans and what they pay on deposits starts narrowing.

That squeeze is already showing up. The RBI pointed out that banks’ profit growth moderated in 2024–25, and one key reason was narrower interest margins.

Second, stability – if deposit growth persistently lags credit growth, banks might be tempted to take on more volatile funding to fill the gap (like short-term market borrowings or certificates of deposit). That can make them more vulnerable to interest rate swings or liquidity crunches.

The RBI is cognizant of this “deposit puzzle.” They haven’t sounded alarm bells (after all, overall deposits are still growing healthily in absolute terms), but the subtext is clear: banks must not neglect their liability franchise in the chase for asset growth.

So, what should we watch in 2026?

If NPAs are this low today, what keeps them low tomorrow? Do we genuinely enter a phase where fresh bad loans slow down too, even if parts of the cycle like microfinance are starting to look shakier? Or do we keep seeing “clean” balance sheets mainly because banks are getting faster at pushing stress out — through write-offs and asset sales — rather than actually pulling money back through recoveries?

And this fintech boom — it’s already been through multiple regulatory crackdowns. But does tighter scrutiny actually change behaviour in a meaningful way? Does it slow down the speed and scale of unsecured digital lending, or does the industry simply adapt and keep moving, just with different wrappers and better paperwork?

The bank–NBFC partnership model is another one. It’s not inherently bad — it’s helped credit reach places banks alone wouldn’t. But can it become truly diversified? Or will we keep seeing the same pattern: too many banks depending on the same few originators, the same kinds of loan pools, the same risk showing up everywhere at once?

And then there’s deposits — the most old-school constraint of all. If loans keep growing faster than deposits, what’s the release valve? Do banks get more creative in attracting savers, build new deposit propositions, and compete harder for household money? Or is the answer simpler and more painful: pay higher deposit rates, accept that funding costs rise, and live with lower NIMs?

These aren’t worries. They’re the moving parts. And 2026 will tell us which version of this story is real.

When Indians expect prices to fall, what happens to their portfolios?

We recently covered how deposit insurance shapes India’s risk appetite — how a policy tool designed to prevent bank runs ended up influencing whether people hold stocks or bank deposits. Today’s story covers similar territory, but the stimulus is different: that of inflation expectations. What happens when people start expecting inflation to fall?

A new research paper by researchers Sumit Agarwal, Yeow Hwee Chua, Pulak Ghosh, and Changcheng Song explores exactly this. Their findings reveal a nuanced relationship between how Indians expect prices to work, how we invest, and why we love liquidity so much.

Let’s dive in.

The natural experiment

In February 2015, in order to aggressively reduce inflation, the RBI formally adopted inflation-targeting. What this means is that, for the first time ever, the central bank committed to reaching the specific inflation rate of 4%, give or take 2 percentage points. Earlier, India followed a ‘Multiple Indicators Approach’, which tracked many variables without committing to a numerical target.

In the absence of a target, the paper says, people never really had uniform expectations of how prices of the goods they buy might change. This varied wildly across cities, age groups, and income levels. Someone in Mumbai, for instance, might expect 8% inflation while someone in Bhubaneswar expected 12%.

However, the 2015 policy changed that. With the presence of a real target that the government is aiming for, households got a concrete anchor. The range of expectations had basically narrowed down. People who expected inflation to be higher would revise their expectations downward, while those who expected lower inflation would mark their assumptions upward. Such an anchor would make the outcomes of a policy change more predictable, and therefore more measurable for the authors.

This expectation of inflation, however, is not the same as what the actual inflation rate might be. You might expect prices to fall by 5% in a year, but they might decline by 1%. This paper deals entirely with those expectations instead of actual rates. The RBI does also guide their inflation policy based on these expectations, but that’s a separate topic.

But what do people actually do with their money when their expectations of inflation change?

That’s where the authors introduce a little economic theory. Say that inflation expectations fall. If the interest rates on bank deposits stay constant, the real return on savings remains high. After all, there is no high inflation to erode the returns you’ve earned. A fixed deposit paying 7%, for instance, looks more attractive if you expect 4% inflation than if you expect 8%. So, to earn those better returns, households should consume less today and save more. This is the consumption Euler equation at work.

But, there’s another force. Lower inflation expectations often come with lower uncertainty about the future. After all, households feel that there are less risks to how high their purchasing power could be over time. If they feel more certain about the future, they don’t need to hoard as much for emergencies at present. The precautionary savings motive weakens, and people might actually spend more and save less.

Which effect wins? It depends on how much liquid savings you have, and that’s what the paper sets out to measure.

Liquidity determines the answer

The researchers found that when the RBI announced the inflation-targeting scheme, households changed their consumption (and investment) based on how much liquidity they already had.

Households with higher liquidity saw the consumption Euler equation effect dominate. As they expected inflation to fall, bank deposits looked more attractive. For households in the highest savings quintile — those with an average of ₹6.24 lakh in their accounts — a 1 percentage point fall in inflation expectations led to an 82 rupee drop in monthly consumption. These households also increased their bank deposits by ₹1,266 per month.

However, for households with lower liquidity, averaging just ₹23,000 in savings, the precautionary savings effect was stronger. The same 1 percentage point drop in inflation expectations led to a ₹54 increase in monthly spending and a ₹443 decrease in bank deposits. Lower uncertainty meant these households felt comfortable spending a bit more rather than hoarding cash. Naturally, this also means that one’s income level can strongly shape how they expect inflation to play out.

In aggregate, these two effects often partly cancel each other out — wealthier households consume less while poorer households consume more. At the macro level, it looks like nothing happened. But underneath, behaviour is moving in opposite directions.

A rush to safe havens

Now, what do these new inflation expectations of higher-saving households mean for their portfolios? That’s where the paper finds a very interesting pattern. While these households now find investment more attractive, they may not increase their risk appetites.

Instead, with lower inflation expectations, they actively reduced their equity and mutual fund holdings, and reallocated funds towards bank deposits. This wasn’t fear-driven selling after a market crash or a crisis. There was no spike in volatility, no panic. It was purely a strategic reallocation.

The logic comes down to how different assets respond to inflation expectations. Bank deposit rates in India are notoriously sticky — they don’t change too often. During the study period, the savings account rate sat fixed at 4% across all major banks. It didn’t move even when the RBI cut rates. As a result, the real return on these deposits rises even when banks hardly change their actual rates — purely because people don’t expect inflation to rise.

Stock returns, on the other hand, do adjust. Equity markets usually price in inflation expectations — when expected inflation falls, nominal returns tend to fall as well, leaving real returns roughly unchanged. This makes the bank deposit more attractive in favor of equity investments.

What also increases its attractiveness is its risk profile. The bank deposit is the ultimate safe asset. People believe that, no matter whether rain or shine, they will earn the return promised by the bank. Its risk-return mix, then, ends up looking much better than that of equity and mutual fund holdings, which households perceive as being far more volatile.

In the deposit insurance story, we saw that Indian households had an unsatisfied demand for safe assets. When they were sure that the government would insure a bigger chunk of their bank deposits, they actively sold their equity holdings and reallocated towards bank deposits. The equities they did sell were PSU stocks — which, in a way, are also safe assets that people strongly believe are protected from failure by the government. In a way, lower inflation expectations reflect that same hunger for safe assets.

One might ask: why not bonds? This is because at the time, India lacked the infrastructure needed to enable large-scale retail participation in the bond market. When it comes to liquid safe assets, bank deposits are automatically perceived as the default.

Debt becomes heavier too

Another telling finding involves debt. Among households in the top savings quintile who had existing loans, a 1 percentage point fall in inflation expectations led to a ₹760 increase in monthly loan repayments.

Why is that? See, most household debt in India carries a fixed nominal interest rate — it’s not indexed to inflation. If, for instance, you have a home loan at 8.5% and you expected 8% inflation, your real borrowing cost was effectively 0.5%. If inflation expectations drop to 4%, your real cost suddenly looks like 4.5%. The debt hasn’t changed, but it feels heavier.

Naturally, households responded by paying down loans faster. After all, as our borrowing isn’t linked to inflation, scheduled repayments would stay the same or even fall if the RBI cut rates. This also supports the effect of the consumption Euler equation.

Conclusion

In our deposit insurance story, we’d mentioned that it’s hard to tie down India’s risk appetite to any one factor. Much like deposit insurance, inflation (and our expectations of it) is a reflection of that appetite, while also influencing it in interesting ways. Policymakers attempting to influence either consumption or investment at a nationwide scale will have to pay heed to these findings.

Wealthier ones respond to falling inflation expectations by saving more and shifting to safe assets, while poorer ones respond by spending a bit more as uncertainty fades. However, lower inflation doesn’t necessarily make households less risk-averse. If anything, lower inflation makes the bank deposit — the most trusted safe asset in India — more attractive compared to the stock market.

Tidbits

Vodafone Idea to pay ₹124 crore a year in AGR dues

Vodafone Idea will pay up to ₹124 crore annually from FY26 to FY31 after the government froze its total AGR dues at ₹87,695 crore. It will then pay ₹100 crore a year till FY35, with the balance reassessed later. The relief improves Vi’s survival chances and ability to raise bank funding.

Source: Business StandardReliance may consider Venezuelan oil if allowed

Reliance Industries said it would consider buying Venezuelan crude if sales to non-US buyers are permitted. The oil could offer cheaper, heavy crude and help diversify away from Russian supplies. Reliance stopped Venezuelan imports in 2025 after US tariffs but says discounted barrels could improve refinery economics.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great Read, looks like this year you guys are on roll. Article writing and story telling is on top level of international article

Really clear breakdown. Loved how you explained the real story behind low NPAs and the rising risk in fintech plus NBFC partnerships. The deposit squeeze angle was an eye-opener too. Great read....