India wants to insure against climate change

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads-up before we dive in. The Tata Capital and LG IPOs are open now. We wrote about them earlier — you can read the full story on Tata Capital here and on LG here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How India compensates climate disasters

The madness behind unlisted shares

How India compensates climate disasters

India gets hit by natural disasters all the time — floods, cyclones, droughts, heatwaves, even earthquakes. Each one leaves behind massive economic damage and human suffering, and it may only get worse from now with accelerating climate change.

Yet, around 93% of disaster-related losses in India aren’t covered by insurance, adding up to tens of billions of dollars in recent years. When disaster strikes, people mostly depend on state aid and donations. Personal insurance, however, rarely shows up in the picture.

That’s why a recent story from Reuters, on how India is considering a nationwide climate-linked insurance scheme, caught our attention. It made us curious: how does India’s disaster compensation system actually work right now? And what exactly is this new thing called “parametric insurance” that policymakers are suddenly so excited about?

Let’s dive in with our findings.

Disaster Management Compensation in India: Status Quo

Under the Disaster Management Act (2005), India has enshrined a set of institutions that provide disaster response funding.

State governments take the primary on-ground relief operations — including emergency response, temporary housing, and immediate rehabilitation — with the central government “supplement[ing] the efforts of the State” through financial grants and logistical support (military aid, supplies, etc.)

The primary funding vehicle is the State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF) of each state, funded by both state and central governments. For severe calamities that overwhelm a state’s finances, the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF), which is fully financed by the central government, steps in to supplement them. But central funds are not released until a full assessment of the damage is approved by a central team, introducing delays in the process.

In addition to these dedicated funds, state governments often have Chief Minister’s Relief Funds and the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund (PMNRF) for public donations.

Notably, official policy emphasizes that aid from these funds is for relief, not full compensation of losses. This means that government payouts are generally assistance for immediate needs like food, shelter, medical aid, and small cash relief — rather than indemnification of total property or income loss.

This naturally takes the conversation to exploring insurance as a risk mitigation tool. After all, insurance as a financial product has done wonders in spreading risk. So why not use it for natural calamities in India too?

Well, for one, traditional insurers have been hesitant to offer affordable catastrophe cover for lower-income households. Many at-risk citizens are either unaware of such insurance or find it too costly. Moreover, such insurers find it difficult to underwrite climate risks because they don’t understand how to monitor them. For instance, how would an insurer with no prior experience in climate risks model floods at granular levels? This leaves the state with no choice but to be the default compensator after such events.

As a result, India’s public disaster funding framework remains fairly inadequate. Payouts are uncertain and delayed, since reliance on government relief funds involves lengthy administrative procedures and central verification. If that weren’t enough, coverage insufficiency remains a problem — government relief is explicitly not intended to fully compensate for losses. Yet, this limited relief still becomes a strain on public finances — especially since payouts are often large, unpredictable, and difficult to plan for — forcing them to reallocate budgets. Lastly, traditional insurance products barely make a dent.

These challenges have prompted Indian policymakers to explore parametric insurance as a complementary tool for disaster risk financing, and that’s what we’ll discuss next.

Enter parametric insurance

In parametric insurance, payouts are triggered by a pre-defined parameter rather than by measured actual loss.

Here’s how that works. In a parametric cover, the policy defines a trigger, like a certain threshold of rainfall, wind speed, earthquake magnitude, or temperature. If that threshold is exceeded (or, in the case of climate disasters like drought, not met), the policy pays out a fixed amount to the insured irrespective of what the loss is. There is no claim process to be followed as the payout is automatic, once the data confirms that the trigger indeed happened.

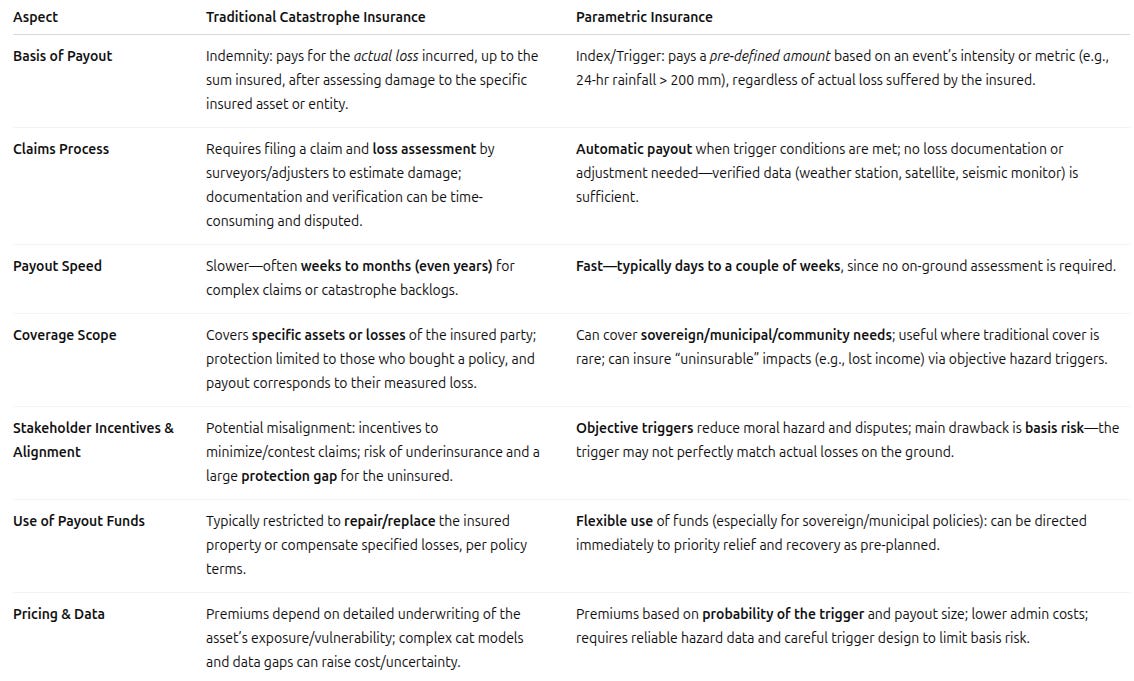

This approach is fundamentally different from traditional indemnity insurance, which pays an amount based on the actual value of damage that is determined during the claims process.

From a governance standpoint, introducing parametric insurance could possibly benefit India’s disaster financing in several ways.

First, faster relief delivery

Unlike standard insurance, parametric triggers make it possible to have near-immediate disbursement of funds after an event. In India, this could mean resources reach disaster zones faster, without waiting for lengthy damage assessments or government approvals. Quick payouts can kick-start relief and recovery, reducing human suffering and secondary economic losses.

For instance, if a cyclone parametric policy were in place for coastal districts, money for relief camps, repairs, and livelihoods could be available within days of the cyclone’s landfall, as soon as the wind speed threshold is verified, rather than weeks under the current system.

Second, reducing fiscal burden

Parametric insurance would shift a portion of disaster costs from the government’s budget to insurers and reinsurers. With an insurance program, the state or central government would pay an annual premium, and in return, the insurer covers extreme event payouts.

While there is a cost to premiums, over the long run this approach can make public expenditure smooth and predictable, limiting surprise outlays. These premium costs are much easier to budget than the huge surprise relief packages.

Third, higher insurance penetration

Parametric schemes can be designed to cover segments that traditional insurance struggles with — such as remote villages, informal housing, or losses like interruption of local markets. For example, poor rural households rarely have property insurance, but a parametric flood insurance program (perhaps run by the state) could provide them payouts when floodwater levels in their area exceed a threshold. Or, it can also cover non-physical losses like a drop in crop yield or business income using an index as a proxy.

Fourth, objective and transparent trigger mechanism

Under the current system, sometimes, how much support an affected area gets is based on how politicized the issue becomes, making the process very subjective and arbitrary. But having clear parametric triggers (e.g. “payout X if rainfall > 300 mm in 24 hours at village Y”) introduces transparency and predictability.

All hands on deck

If India rolls out parametric disaster insurance nationwide, it would require tight coordination across every tier of governance and finance.

At the central government level, ministries like Finance and the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) would likely sponsor or co-sponsor national or sovereign policies. They would set guidelines, co-fund premiums, and work with reinsurers so that there is enough supply of such policies. The Centre’s role would shift a bit from reactive relief disbursement to strategic risk pooling and premium financing.

State governments would act as policyholders for their regions, purchasing covers for floods, droughts, or cyclones that trigger automatic payouts. These funds could then be used immediately for relief and rehabilitation instead of waiting for central approval. And the states can design these policies based on their climate profile.

This has already been piloted in some states. Nagaland, for instance, is very prone to excess rain, which frequently causes landslides and flooding for them. In response, they designed a rainfall-linked insurance program called Disaster Risk Transfer Parametric Insurance Solution (DRTPS) that has worked quite successfully. In Rajasthan and Gujarat — two of India’s hottest states — women are provided heatwave cover, with temperature being the parameter.

Finally, insurers and reinsurers would design and underwrite such products, manage risk-sharing pools, and handle data-driven trigger verification. For instance, the largest reinsurer in the country — GIC Re — could provide domestic reinsurance, while global players provide additional backing so that these products become a reality.

No silver bullet

However, parametric insurance isn’t a perfect solution. Its biggest flaw lies in what experts call basis risk, which is the gap between what the trigger says and what actually happens on the ground.

For instance, if a flood devastates a district, but the rainfall gauge nearby records slightly less than the threshold, no payout happens. The people who suffered get nothing, even though they clearly deserve help. In other words, the parameter can be too objective.

Conversely, a payout might also be triggered for an event that barely caused any damage, just because the parameter was crossed. That mismatch can erode trust and make communities feel cheated — and that’s the trade-off between speed and precision in this model. That’s where the quality of data monitoring and capturing play the deciding factor in how effective such an insurance program can be.

Conclusion

For now, we are only studying and discussing the idea, and no formal nationwide plan exists yet. Designing something this complex — with fair triggers, accurate data, and buy-in from dozens of states — will take time.

But early pilots in states like Nagaland and Rajasthan show promise. And India is hardly the first country to try this out. Abroad, Fiji’s sovereign cyclone policy showed how quickly parametric insurance can inject funds when disaster strikes.

If India manages to combine sound data, transparent governance, and strong public-private coordination, parametric insurance could evolve from a niche experiment into a national disaster resilience framework. It’s not foolproof, but it might be the fastest, fairest way yet to get help where it’s needed, when it’s needed.

The madness behind unlisted shares

A few years ago, the world of unlisted shares was mostly just a private bazaar for the rich. In this world, a few well-connected, privileged investors quietly bought tiny slices of promising companies before they went public. You needed brokers who knew promoters, lawyers who could make paperwork move, and enough patience to sit on an illiquid bet for years. It was the kind of thing a wealth manager might whisper about over golf.

To a degree, that old world has changed. What was once a closed circuit of high-net-worth investors is now being sold to ordinary savers as a ticket to the future.

Platforms that once helped employees sell their startup ESOPs now call themselves “unlisted stock exchanges”. Influencers make videos explaining how to get in early on the next big IPO before anybody else. And Telegram groups with thousands of members promise access to “pre-IPO deals”.

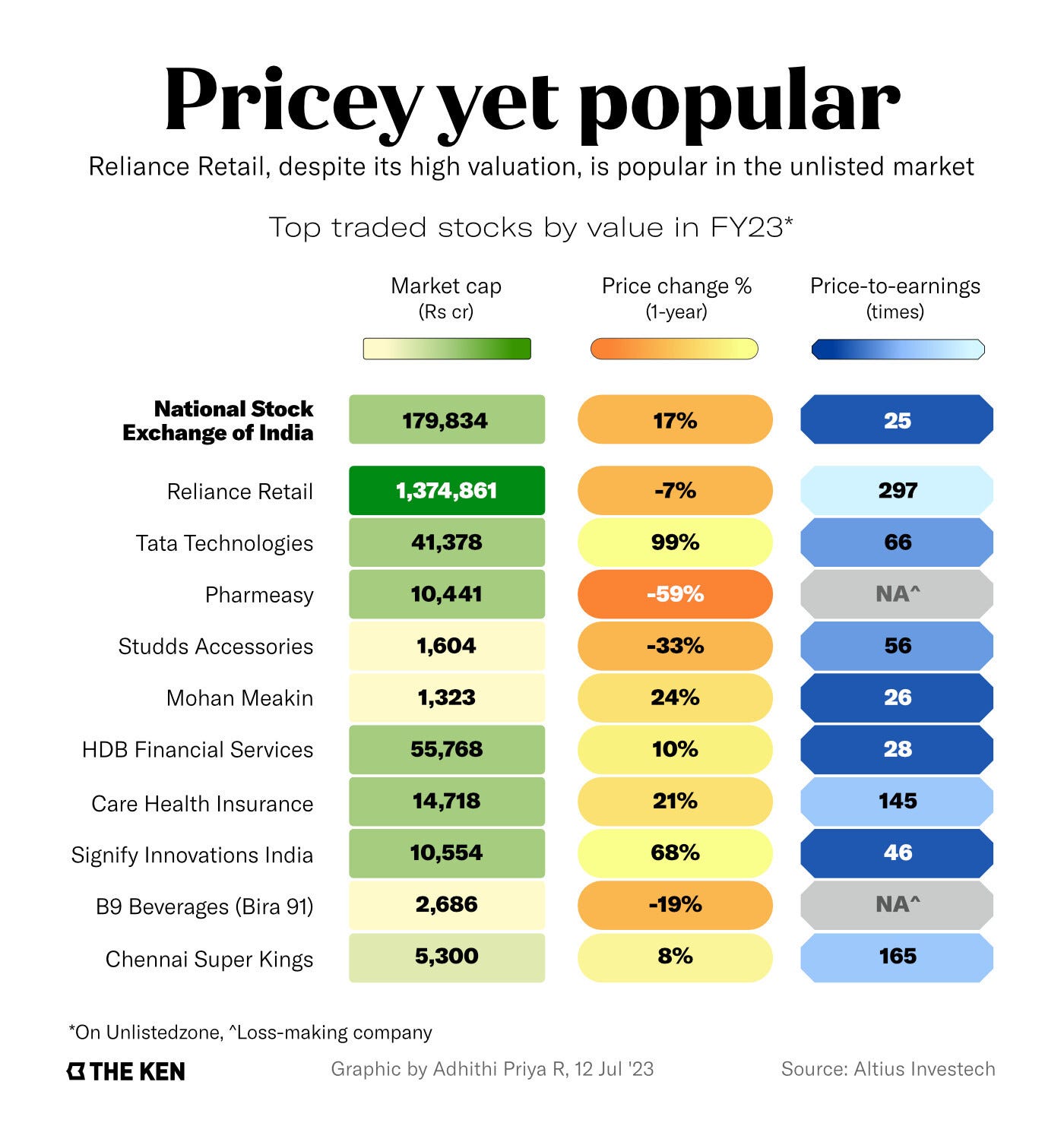

But beneath the shiny veneer, it’s a really messy world. It might look like a market, but hardly works like one. Recently, we covered the Tata Capital IPO, which had a lot of hype in the unlisted market, and therefore unbelievably-high prices that didn’t justify the business. However, its unlisted price came crashing down, leaving lots of investors with painful losses. And Tata Capital is hardly the first company that went through this cycle.

Let’s dive into how the Indian unlisted share market works, and why it’s such a breeding ground for mispriced stocks.

What exactly are unlisted shares?

At the simplest level, an unlisted share is a piece of equity in a company that hasn’t yet listed on the stock exchange. These are often large, well-known firms whose shares aren’t available on the NSE or BSE yet. They can also be fast-growing private startups that may or may not ever list.

The first question is, how do these shares even end up out in the wild?

Here’s how. Every company issues stock to founders, early employees, and investors. Over time, some of them want to sell — maybe to diversify, pay taxes, or lock in some of their gains. However, unlike publicly-listed companies, there’s no formal exchange for such sales. So if they want to sell, where do they go?

A patchwork of middlemen fills that gap. They match these sellers with buyers, record a deal privately, and take a commission for the service. Legally, such a change of hands is allowed as long as the company’s articles are followed.

For years, that world stayed small and discreet, but fintech companies changed the equation. They digitised paperwork, aggregated demand, and suddenly turned what was a niche, illiquid trade into something that looked like an actual asset class.

And the pitch behind expanding this market was seductively simple: why wait for the IPO when you can get in before it?

A market only in name, but not in function

But this simple pitch masked a big problem with how the unlisted world really worked. While usually described as a “market”, the unlisted world is not great at performing the core function of a market — price discovery.

Think about how a real market works. Prices emerge through constant negotiation between thousands of buyers and sellers. Every order is visible in real time for everyone to see. When two sides agree on a price, that trade is matched, cleared, and settled through a central system. Prices move only when new information arrives — a quarterly result, a merger, or a policy change. And various people react to new information differently.

Past traded prices become references for future prices, and over time, the market’s collective judgment converges on what is considered fair value. This is how any market — including NSE and BSE — works.

The unlisted space, however, lacks most of these features. It has no central exchange, no order book, and no record of trades. Prices are based on whatever one broker says someone else paid, which might even have been weeks ago. There’s no public information about the company that you can use to verify this price quote, just hearsay. Sometimes, the price quote is just a sentiment that reflects mere rumour rather than anything truly substantial.

In effect, there’s no structured price discovery at all. One seller or platform might quote ₹1,200, another might say ₹1,800, and both can claim to be right because there’s no way to build a consensus on fair price.

To some degree, this is also how a black market works, where banned goods are traded at obscenely-high prices, and there’s no way to figure out fair value. However, the unlisted space isn’t exactly illegal, as owning and trading a stock is legal — making it neither black, nor white, but a “grey market”.

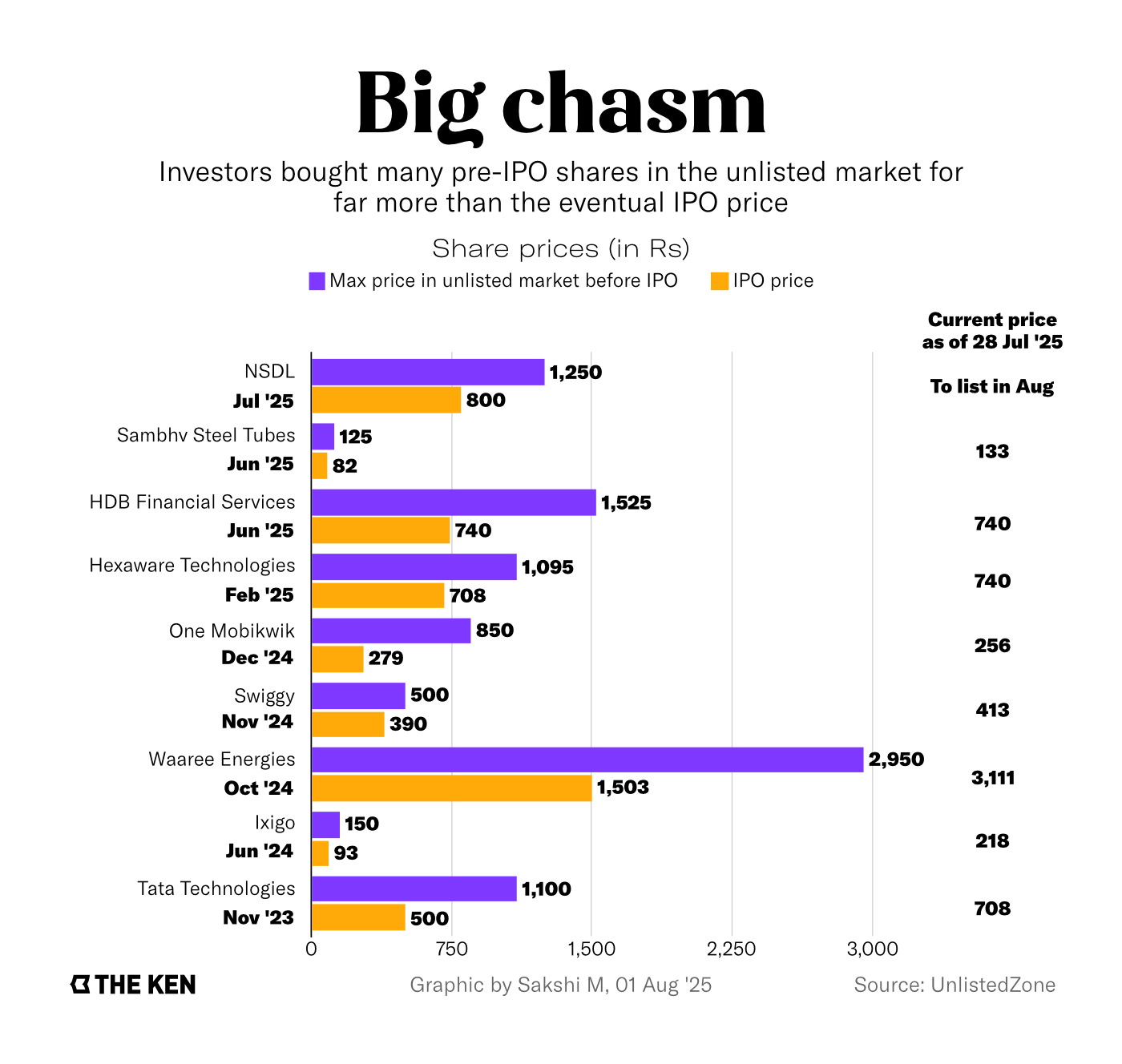

A “grey market” is very prone to incorrectly putting a price tag on things, making it way more volatile than real markets. And unlike the NSE or BSE, the grey market doesn’t have circuit breakers for when prices become abnormally high or low. Just look at the price gaps between when a stock was unlisted versus when it became publicly-listed.

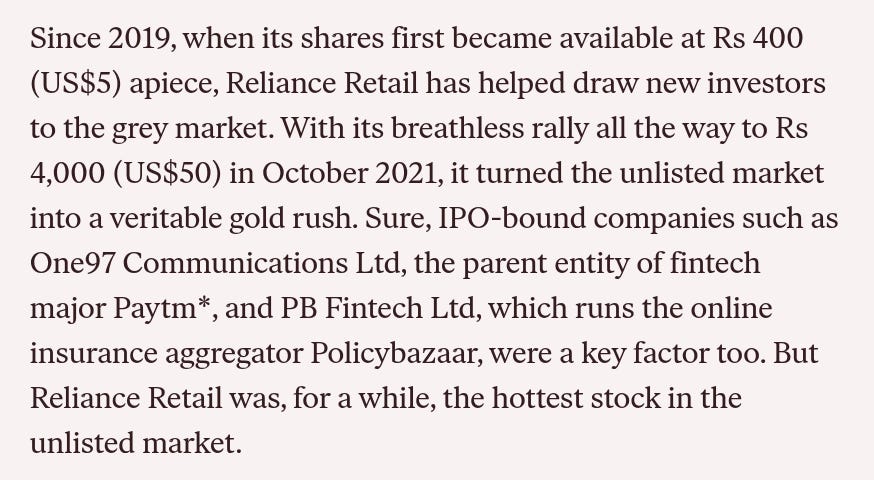

This entire house of cards runs on blind faith that someone, somewhere, will buy it for more later. But then the cards crumbled first with Reliance Retail.

When the music stopped

As a fast-growing subsidiary of India’s largest conglomerate, Reliance Retail offered a safe way to own a slice of the Reliance growth story. Who doesn’t want a piece of Reliance, especially if you could get your hands on it before everybody else? Based on that hype, prices in the grey market soared past ₹4,000 a share.

Then, in 2023, Reliance Retail restructured its share capital. It issued fresh bonus shares to employees and adjusted its internal valuation. Basically, the number of shares in circulation multiplied, meaning that the per-share value automatically fell. Structurally, though, nothing about the business changed. As a whole, it was just as valuable as it was before this change. But in the unlisted world, this change hit like a shock.

There was no stock-exchange announcement or official clarification. But brokers who knew this simply began quoting new, lower prices, and the price halved. Within days, the same shares that had changed hands at ₹4,000 were fetching half that. Thousands of small investors who had bought through intermediaries saw their holdings halved overnight, without warning or explanation.

This wasn’t really a scam; rather, it was a faulty system unravelling itself.

SEBI takes notice

Naturally, SEBI couldn’t help but take notice of this. In December 2024, it finally stepped in with a formal clarification, straight up calling these platforms “illegal”:

SEBI’s logic was simple: unlisted shares are far too easy to manipulate. A seller can quote any number, call it a “price,” and if enough people believe it, that fiction becomes fact. That makes the space perfect for pump-and-dump schemes — where a few big players set a high price and spread excitement among retail investors, who are tempted to rush in, further increasing the price. Those same big players then sell high, after which the hype fades, and retail investors find their holdings valued at a steep loss.

And the problems don’t end there. Owning unlisted shares means handling taxes and disclosures manually. You have to track dividends yourself, and when you sell, you must calculate a “fair value” on your own. None of the safety rails that protect listed retail investors apply here.

A game of psychology and exclusivity

The Ken’s coverage of the Reliance Retail fiasco presents the grey market quite aptly:

If the flaws are this obvious, why does the frenzy continue? Because, well, stocks aren’t always about fair valuations, but also about psychology. The dream of “getting in early” and outsmarting everyone else is irresistible. It’s like getting your hands on a shiny new car before everyone else. In this narrative, “unlisted” doesn’t sound like “unregulated”; it sounds like “exclusive”.

For instance, when Tata Technologies listed last year, its IPO price was less than half of what its unlisted stock had traded at months earlier. Yet, the listing itself doubled on debut. This only deepened a popular myth: the real money is made before the IPO.

The trouble is, unlisted shares go up easily and fall silently. In listed markets, a bad day shows up on every screen. But in unlisted ones, there’s no ticker or daily reminder of risk and volatility. It is as unpredictable as it can get.

Tidbits

Deloitte admits AI use in faulty report

Deloitte will refund part of a A$439,000 ($290,000) payment to the Australian government after its AI-assisted welfare review report contained multiple errors. The firm admitted using generative AI, prompting lawmakers to call it “partial apology for substandard work.”

Source: Financial ExpressSolar and wind outpace power demand

For the first time ever, renewable energy growth has surpassed global electricity demand. Solar generation jumped 31%, and wind grew 7.7% in early 2025, adding over 400 TWh more than demand. Experts say the shift signals fossil fuel use peaking soon.

Source: Business StandardEli Lilly to invest $1 billion in India

Eli Lilly will invest over $1 billion in India to expand manufacturing and supply chains, working with local drugmakers. The company will also set up a new Hyderabad facility to oversee its contract manufacturing network and hire engineers and scientists.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Krishna

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉