Inside India’s biggest NBFC IPO yet

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Tata Capital: cutting through the IPO hype

India’s health labor market

Tata Capital: cutting through the IPO hype

October 2025—the month of Dussehra and Diwali, is also shaping up to be India’s biggest-ever IPO month, with companies expected to raise more than $5 billion or around ₹44,000 crores.

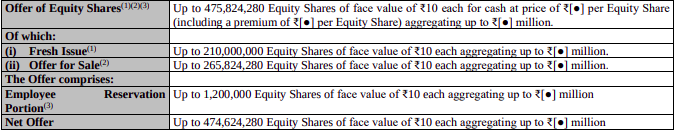

The first big one on the block is Tata Capital, which plans to raise about ₹15,500 crore through a mix of fresh equity and an offer for sale.

But even before the listing, the drama has been intense. In the unlisted market, Tata Capital’s shares crashed from a peak of ₹1,125 in April to around ₹735 today. The company itself set a price band of ₹310–326 — far lower than the unlisted price—leaving many pre-IPO investors staring at losses of over 70%.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen this. HDB Financial went through the same thing—a sharp pre-IPO fall and then only a modest premium when it listed. Still, despite all this, Tata Capital’s IPO is set to be the biggest ever by an Indian NBFC. Which raises the real question: what kind of business is Tata Capital, and where does it stand in India’s credit story?

NBFCs want to fill India’s credit gap

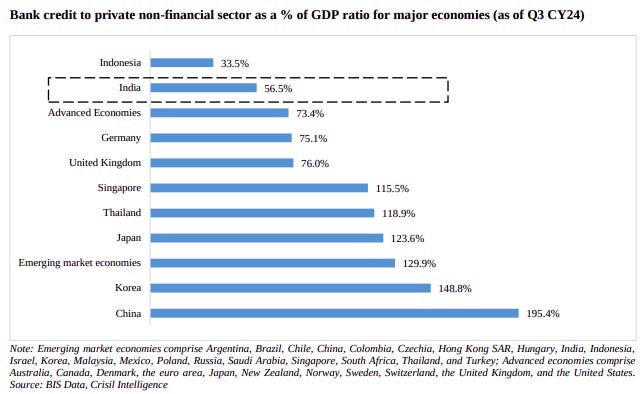

India is one of the fastest-growing economies, but it doesn’t have enough credit to match that growth. Our credit-to-GDP ratio is just 56.5%. In richer countries, it’s over 80%. In China, it’s close to 200%. And we also have far fewer bank branches per person than many other countries.

The reason for that is simple: historically, Indian banks catered to salaried workers in big cities, leaving MSMEs and informal sector workers in smaller towns underserved. Without physical bank presence, many were effectively shut out of credit.

Things began to change when India built out its digital public infrastructure. UPI made payments seamless. The RBI’s Account Aggregator framework meant lenders could now use digital data to judge creditworthiness quickly. Suddenly, distance and paperwork weren’t such big obstacles anymore.

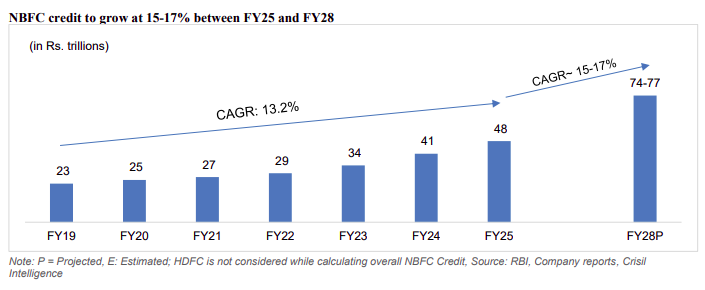

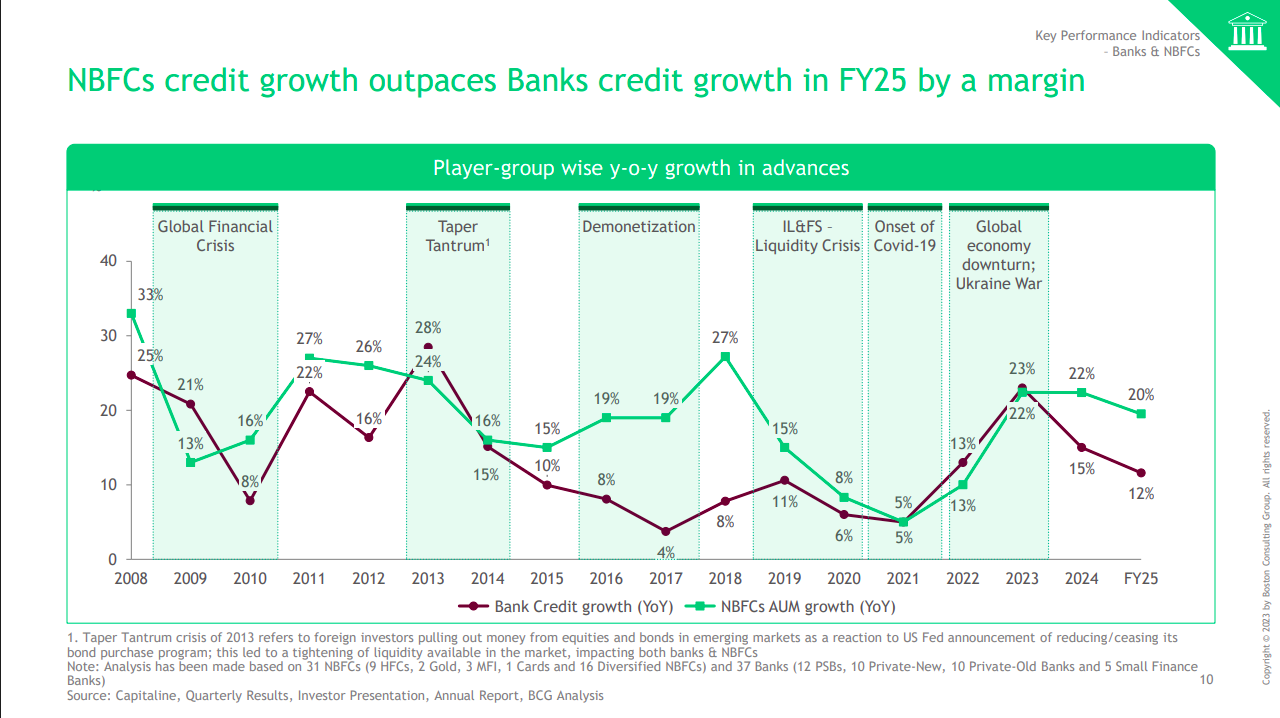

And this is exactly where NBFCs stepped in. They began offering quick, flexible loans in places banks had ignored. As a result, NBFC assets under management grew from about ₹2 lakh crore in the early 2000s to over ₹48 lakh crore by FY25. Between 2019 and 2025, their loan growth outpaced banks, at 13% a year. And according to CRISIL, they’re set to keep growing at 15–17% annually for the next three years.

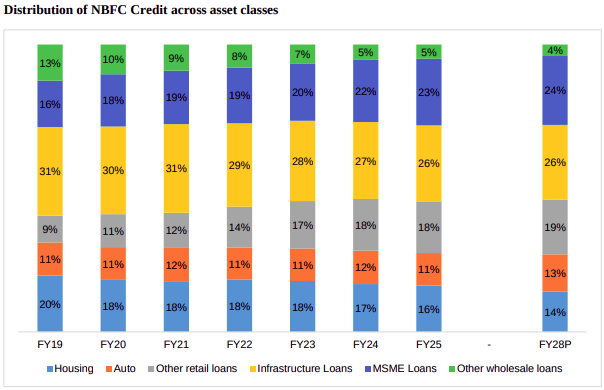

Most of this growth has come from retail lending — home loans, vehicle loans, and MSME financing. Together, these three make up more than half of the industry’s loan book. Infrastructure loans may be larger in size, but they’re tightly regulated and dominated by banks. Tata Capital, too, has chosen to stay heavily retail-focused.

How to evaluate an NBFC

So how do NBFCs actually make money? Their model is simple. They borrow funds—usually through bonds, debentures, or bank loans, since they can’t accept customer deposits. These funds are then lent out to consumers in underserved areas and sectors.

The difference between what they borrow at and what they lend at is their profit margin, called the net interest margin or NIM. But here’s the catch: NBFCs don’t have cheap deposits like banks do, which means their borrowing costs are higher. To offset this, they either lend at higher rates or run more efficiently.

That leads to trade-offs. Secured loans backed by collateral are safer but less profitable. Unsecured loans earn higher margins but carry bigger risks of default.

So when you evaluate an NBFC, three things matter most.

First, the financing mix: how cheaply and how diversely they borrow.

Second, the asset quality: whether borrowers are reliable and whether the balance sheet can withstand stress.

And third, profitability: whether margins are strong, either because of a smart loan mix or because of operational efficiency.

There are other business models like co-lending that we won’t get into here, as they’re less relevant for how Tata Capital works.

Behind India’s third-largest NBFC

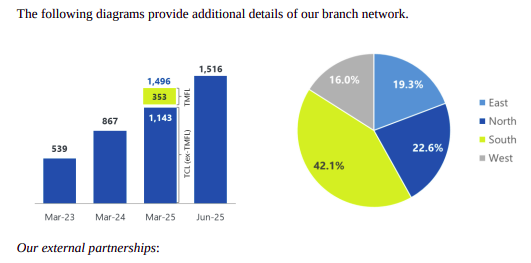

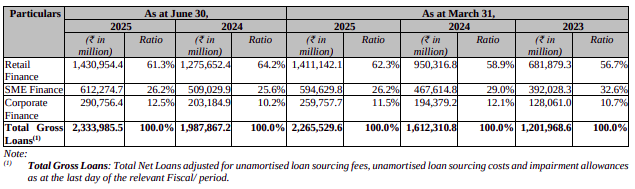

Tata Capital started in 2007. Today, it’s India’s third-largest NBFC with a loan book of ₹2.33 lakh crore. Between March 2023 and March 2025, that book grew at a staggering 37% a year. The company now serves 7.3 million customers through nearly 1,500 branches in 27 states. And 98% of its loans are small-ticket, under ₹1 crore.

Scale, like in most Tata businesses, is its biggest strength.

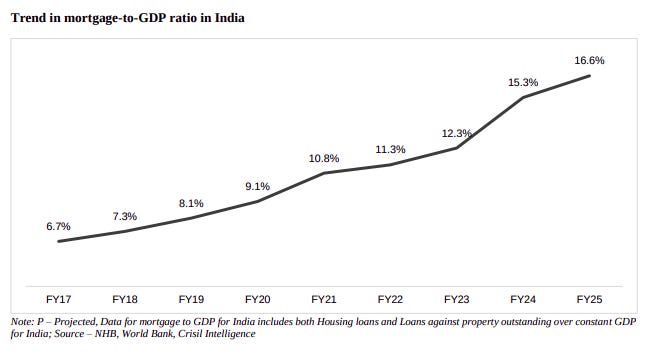

The loan book itself shows where Tata Capital wants to play. Over 61% is retail finance—home loans, loans against property, and personal loans. Home loans alone are 17%, a deliberate bet on India’s housing shortage of around 100 million homes and very low mortgage penetration. With rising incomes and government housing schemes, Tata Capital sees a long runway in mortgages.

In May 2025, it also merged with Tata Motors Finance, adding a significant chunk of vehicle loans to its portfolio. SME finance now makes up 26% of the loan book, providing small businesses with working capital, equipment, and supply chain credit. The rest, about 12.5%, is corporate finance, which is usually dominated by banks.

Underneath the financials

Now, let’s talk numbers.

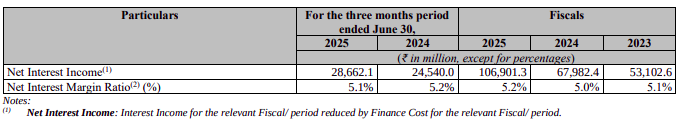

Tata Capital’s revenue surge has matched its growth. In just two years, its interest income more than doubled, from about ₹11,900 crore in FY23 to nearly ₹25,700 crore in FY25. Net interest income grew 42% annually to ₹10,700 crore.

But profits as a whole tell a different story. In the same FY23-FY25 period, profit after tax rose just 11% year-on year from ₹2,946 crore to ₹3,655 crore. Q1 FY26 was stronger, with PAT of ₹1,041 crore—double what it earned a year earlier.

Why this mismatch between revenue and profit?

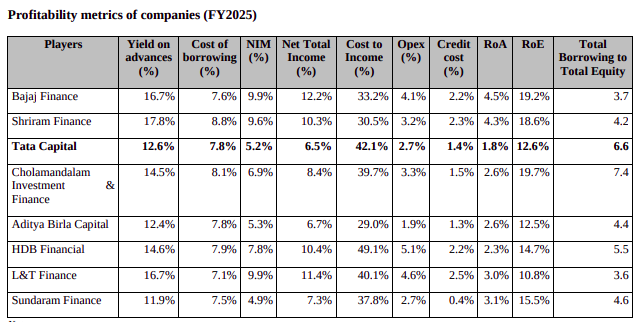

Let’s start with the funding side. Tata Capital borrows at just 7.8%—one of the lowest in the industry. Many mid-tier NBFCs pay 8–10%. Its borrowings are well spread out, with no single lender providing more than 10%. And thanks to its AAA rating and the Tata brand, it has access to cheap global capital—like the $400 million it raised in January 2025 at just 5.4%.

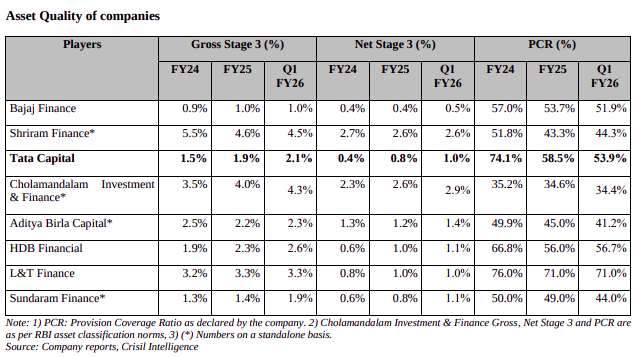

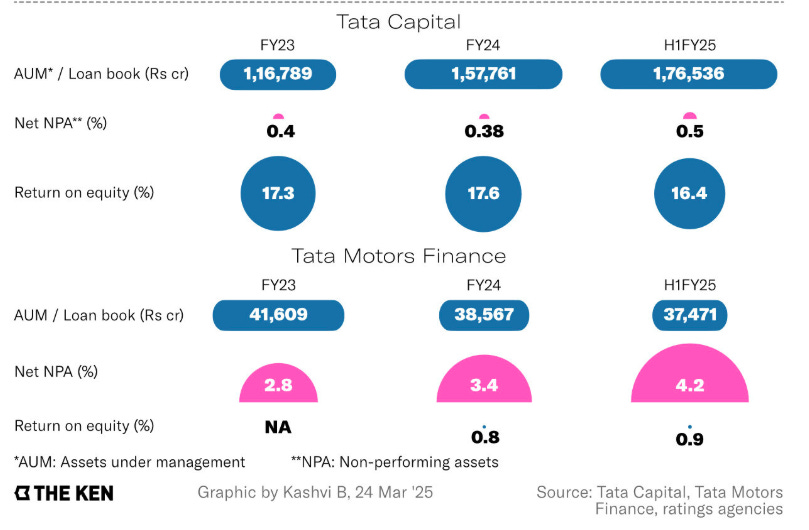

Now, the asset side. Less than 20% of Tata’s loan book is unsecured, compared to 25–30% at Bajaj Finance. Loans overdue by more than 90 days—Stage 3 loans—are among the lowest in the industry. But the merger with Tata Motors Finance dragged this down. TMFL had a gross NPA of 7.1% and a net loss of ₹181 crore in FY25, compared to Tata Capital’s standalone NPA of just 0.5%. That’s the main reason profit growth lagged revenue growth.

Finally, profitability. Tata Capital’s net interest margin is 5.1%. That’s well below Bajaj Finance’s ~10%. But instead of chasing risky margins, Tata has focused on stability. It’s improving efficiency instead. Its cost-to-income ratio dropped from around 42% in FY25 to 37% in Q1 FY26, inching closer to Bajaj’s 35%. AI-based credit scoring, digital loan processing, and automated collections all played a part here.

The risks

But there are risks — and they’re not small.

The first is the Tata Motors Finance merger itself. Auto financing is a tough business. Vehicles depreciate quickly, and commercial vehicle demand depends on industries like construction, freight, and mining, which are highly cyclical. As Tata Motors’ captive financier, TMFL often lent aggressively to boost car sales, even at the cost of credit quality. That baggage is now part of Tata Capital.

Second is interest rate risk. Around 55% of Tata’s borrowings are fixed, while 64% of its loans are floating. If the RBI cuts rates, loan income falls faster than borrowing costs, squeezing margins.

Third is competition. Banks are pushing harder into retail lending. With deposits, their cost of funds is much lower. If they cut rates aggressively, Tata Capital must either match them or risk losing business.

Fourth is regulation. Tata Capital is one of 15 “upper-layer” NBFCs. These are regulated almost like banks, though they can’t take deposits. The tighter rules make the system safer but also increase costs and reduce flexibility. And here’s the kicker: all upper-layer NBFCs must be listed by the end of 2025. That’s one reason Tata Capital’s IPO is happening now.

Finally, there are the big external risks. A slowdown in real estate would hurt Tata’s mortgage-heavy book. Weak transport activity would make vehicle loans harder to collect. And if banks come under stress, NBFCs often struggle to raise funds.

Fundamentals over hype

So where does that leave Tata Capital? On the plus side, it has scale, a trusted brand, cheap funding, a safer loan book, and improving efficiency. On the minus side, it’s dealing with the TMFL merger drag, thinner margins compared to peers, and growing competition from banks.

If you only looked at the sky-high unlisted market prices, you’d miss these details. What really matters now is whether Tata Capital can manage these risks while building on its strengths.

Either way, this IPO—India’s largest ever by an NBFC—is going to be one of the most closely watched listings of the year.

India’s health labor market

The World Bank just published a fascinating study on Indian health labor markets, and honestly, the findings are pretty eye-opening. This isn’t just about doctor shortages or hospital staffing—it’s about understanding one of the world’s largest healthcare workforces, how it’s changing, and what that means for over a billion people.

The Big Picture

First, let’s zoom out and understand what this study is all about.

India today has around 50 lakh active healthcare workers. That sounds impressive on paper. But when you spread that workforce across a population of 140 crore people, the scale of the challenge becomes obvious.

The World Bank’s new study takes a different approach to understanding this workforce. Instead of just counting how many doctors or nurses exist, it looks at healthcare as a labour market. These are workers who make choices—where to work, how many hours to put in, whether to move abroad. And those choices are shaped by wages, working conditions, career prospects, and family responsibilities.

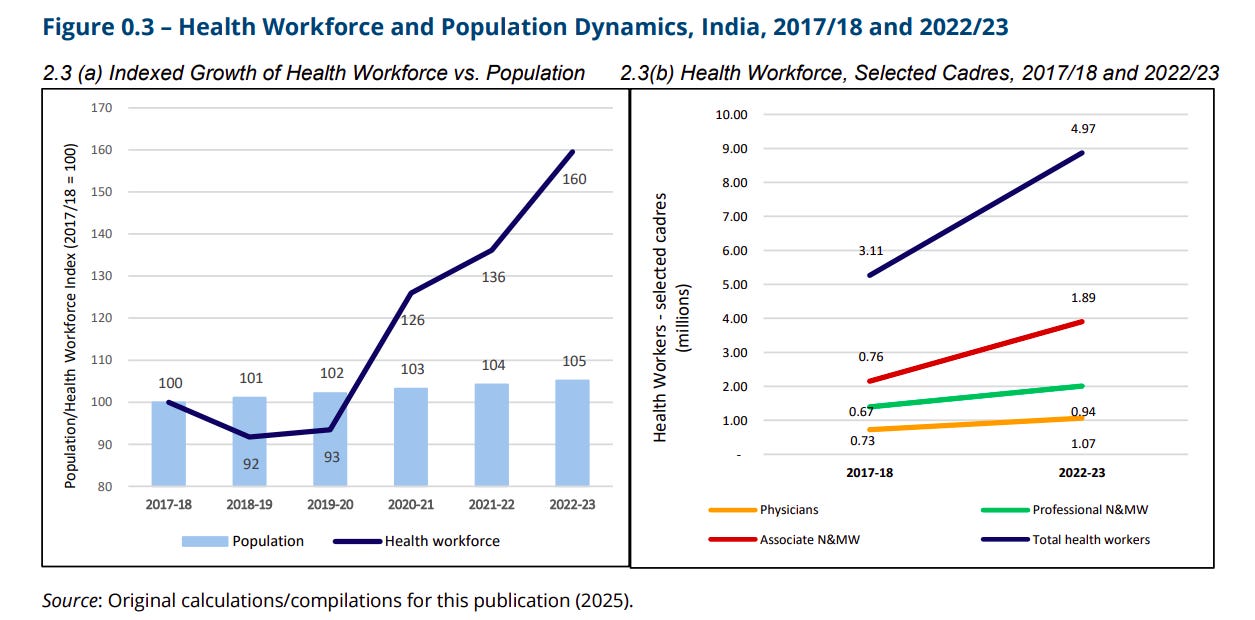

Since 2017, India’s healthcare workforce has grown by a remarkable 60%. That’s far faster than the 6% growth in population over the same period. But the picture isn’t straightforward. The growth is uneven. There are severe shortages in rural areas, training quality is uneven, and a large share of workers don’t meet formal qualification standards.

So the question isn’t just, “do we have enough doctors and nurses?” It’s “where are they, how well are they trained, and how do they respond to the market?”

Size and Composition

Let’s start with the numbers.

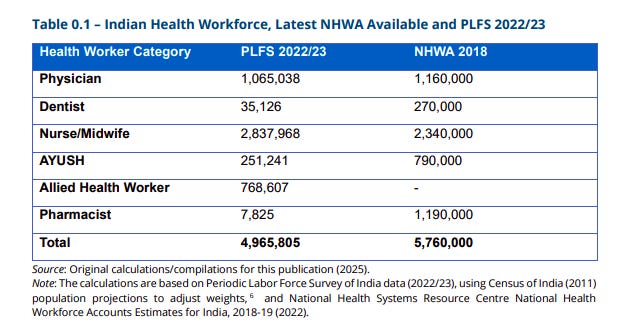

India has about 10.6 lakh doctors, 28.4 lakh nurses and midwives, 2.5 lakh AYUSH practitioners—that’s traditional medicine like Ayurveda and Homeopathy—and 7.7 lakh allied health workers like lab techs and therapists. Put together, that’s roughly 50 lakh people.

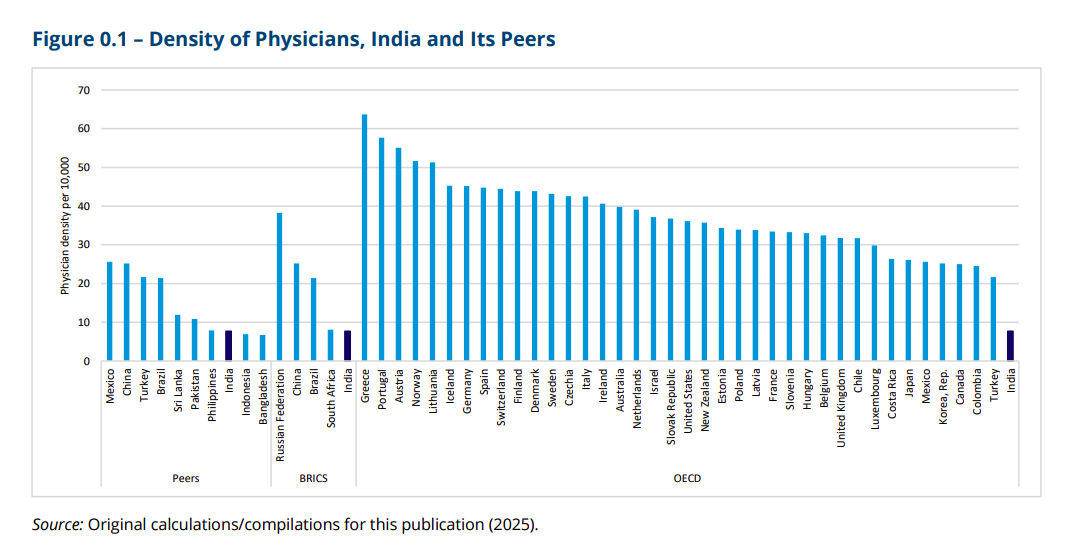

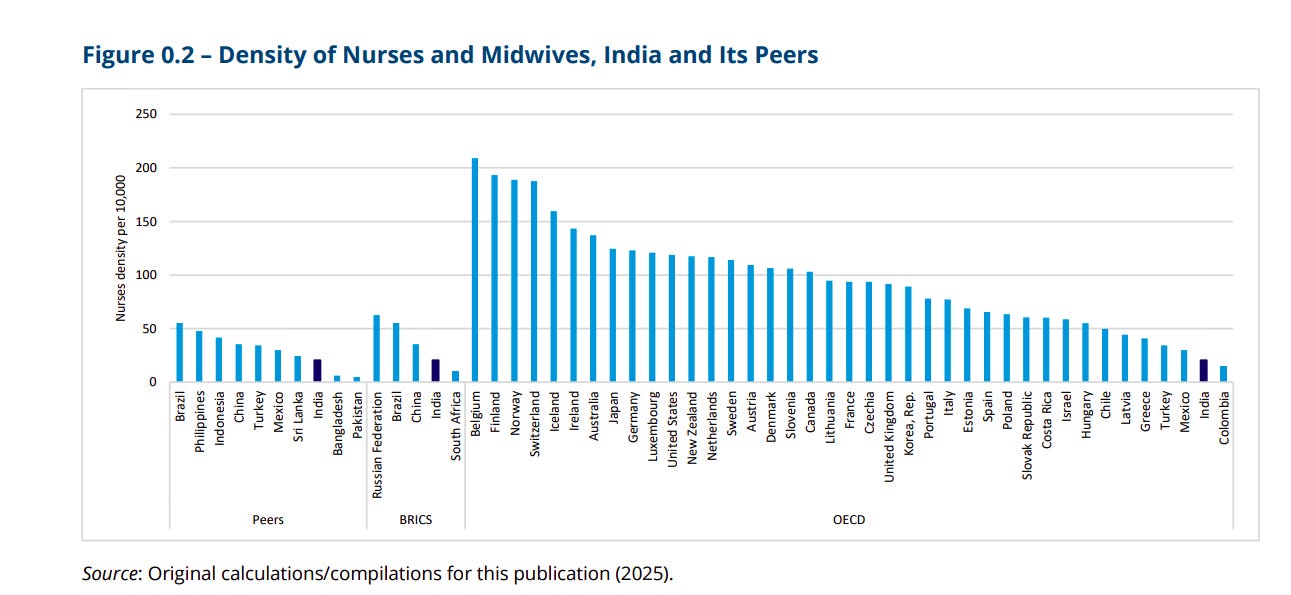

But it’s still not enough. India has about 28 health workers per 10,000 people. The World Health Organization says you need at least 44.5 for basic health coverage. Indonesia, the Philippines, and even some other middle-income countries are already above that threshold. In richer OECD countries, the number is 128 — more than four times India’s level.

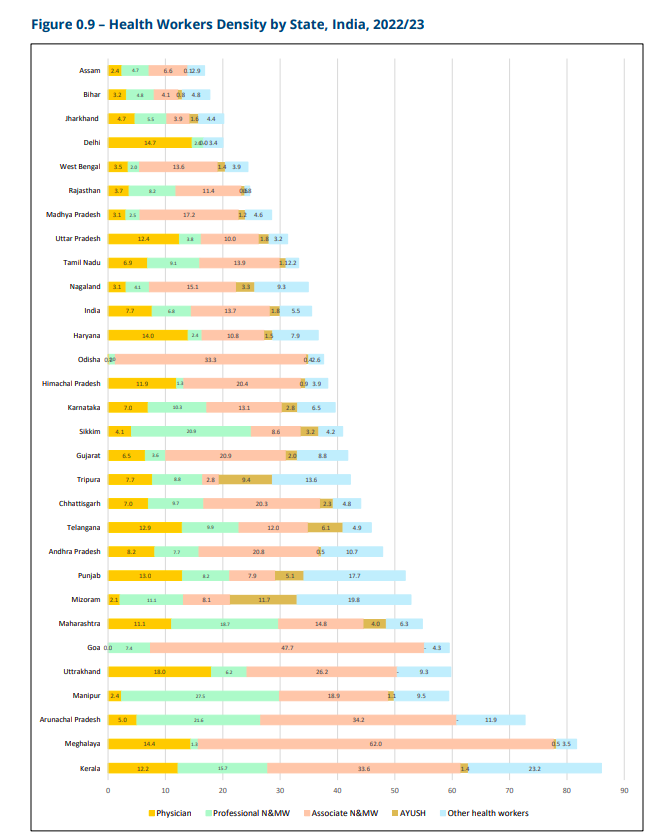

Let’s break it down further. Doctors are especially scarce. India has just under 8 doctors per 10,000 people. That’s about the same as the South Asian average, but far behind the BRICS average of 20 and nowhere close to the OECD average of 34.

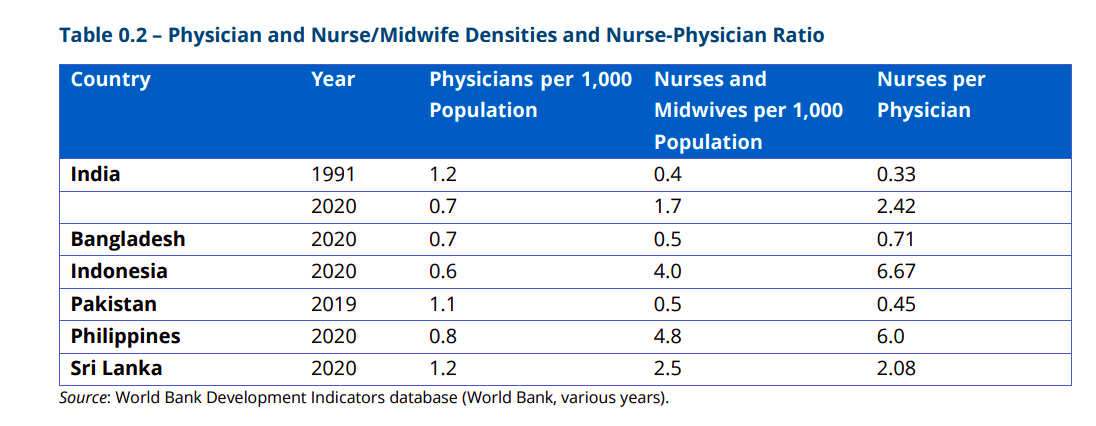

On nurses, the situation is a little better. India has 20 nurses per 10,000 people, which is more than the South Asian average of 15. But it’s still less than half of BRICS and barely a fifth of OECD levels.

The nurse-to-doctor ratio tells another story. India has about 2.6 nurses per doctor, which looks good compared to neighbors like Bangladesh or Pakistan, where the ratio is below 1. But the distribution is uneven. In Delhi, for instance, the ratio is just 0.14 — which means doctors are handling routine tasks that nurses could easily take on. In countries like Indonesia or the Philippines, where there are six or more nurses per doctor, that burden is shared far more efficiently.

The good news is growth. Since 2017, the number of doctors has risen by nearly 50%, professional nurses by 40%, and nursing assistants by over 150%. This is thanks to a massive expansion of training institutions—612 medical colleges today compared to 335 in 2010, and more than 5,200 nursing colleges compared to less than 3,000 a decade ago. Much of this expansion has come from the private sector, especially in the southern and western states.

But more doesn’t always mean better. Nearly 40% of India’s health workforce doesn’t meet the formal qualification standards for their role. Among nurses and midwives, it’s more than half. That raises tough questions about the quality of care.

Informal health providers

And then there are the informal health providers. In many parts of rural India, these are the people most patients actually turn to, actually, they can account for up to 68% of healthcare providers. They may not have formal medical degrees. Some have paramedical training, others have learned on the job. They run small clinics, make house calls, and often allow patients to pay later.

Estimates suggest that in some rural areas, informal providers make up as much as two-thirds of all health workers. Communities trust them because they’re accessible, affordable, and they take time with patients. In fact, some public hospitals even collaborate with them — for instance, in managing tuberculosis cases in Mumbai.

But here’s the catch: they aren’t regulated. They aren’t counted in official statistics. And their training, when it exists, is inconsistent. Some provide competent care, while others overprescribe antibiotics or deliver treatment that’s outright harmful.

India’s laws don’t recognize them, which means there’s no framework to upgrade their skills or hold them accountable. It’s a blind spot that complicates any effort to measure or improve the health workforce.

Geographical distribution of healthcare workers

Most of India’s doctors and nurses are concentrated in cities. Over 60% of doctors, professional nurses, and AYUSH practitioners work in urban areas, even though just over a third of Indians live there. Dentists and pharmacists are overwhelmingly urban too.

The exception is associate nurses and midwives. Around 60% of them are based in rural India, and their numbers have exploded in recent years. Between 2017 and 2023, the rural associate nurse workforce grew by more than 240% — from 3.3 lakh to 11 lakh. This surge is closely tied to Ayushman Bharat, the government’s flagship health reform, which has rolled out 1.5 lakh health and wellness centres across the country. These centres depend heavily on associate nurses to function.

But even with these gains, the urban-rural divide remains stark. Southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka have relatively high densities of health workers, while Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh lag far behind. Bihar, for example, has just 3.2 doctors per 10,000 people. In Uttarakhand, that number is 18. Most OECD countries are above 30.

And the imbalance isn’t just about numbers. It’s about the mix. Some states, like Delhi and Haryana, have more doctors than nurses, which is inefficient. Ideally, you want nurses to handle routine care so doctors can focus on specialized tasks. When the ratio is skewed, doctors end up overburdened, and patients wait longer.

Public vs Private sector

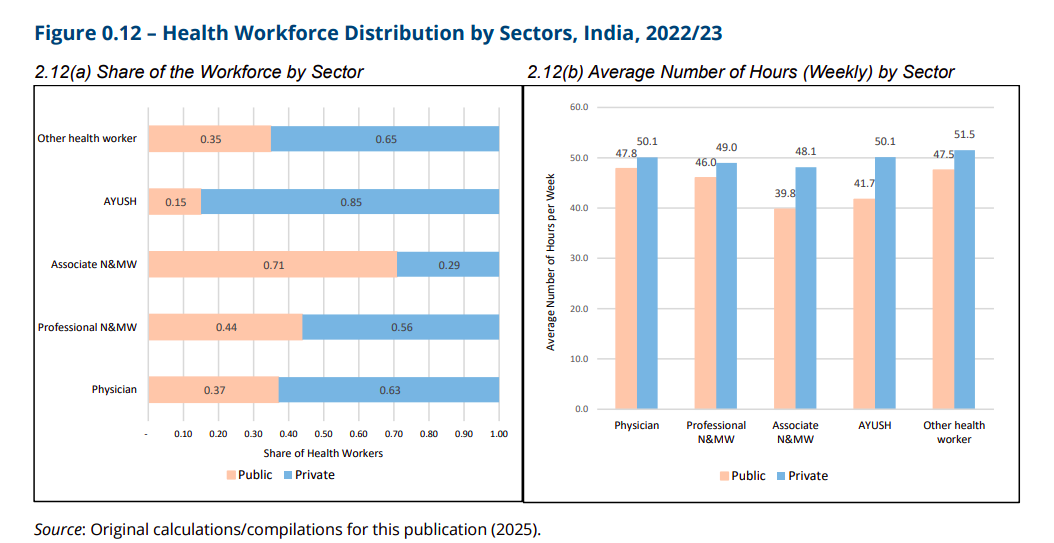

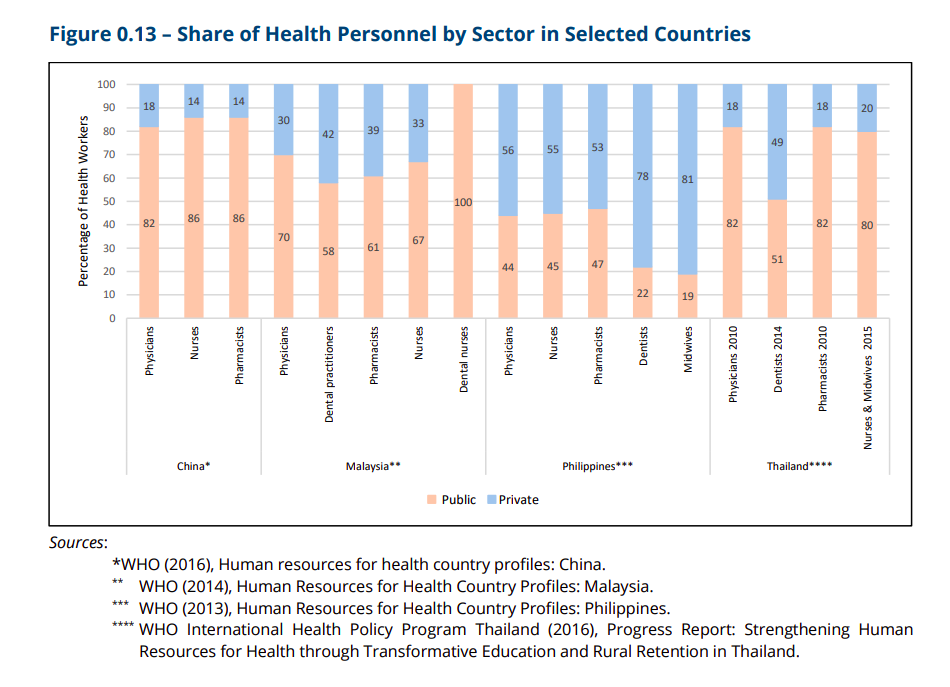

Here’s something that sets India apart. Most health workers here are in the private sector. About two-thirds of doctors, over half of nurses, and a staggering 85% of AYUSH practitioners work privately.

Compare that to countries like China or Thailand, where 80% of health workers are employed in the public system. Even in the Philippines or Malaysia, the split is closer to half-and-half. India is an outlier, with a workforce dominated by private employment.

That has big implications. The government can’t simply assign where people work or directly set their wages. Instead, it has to influence the market through incentives, subsidies, and regulations.

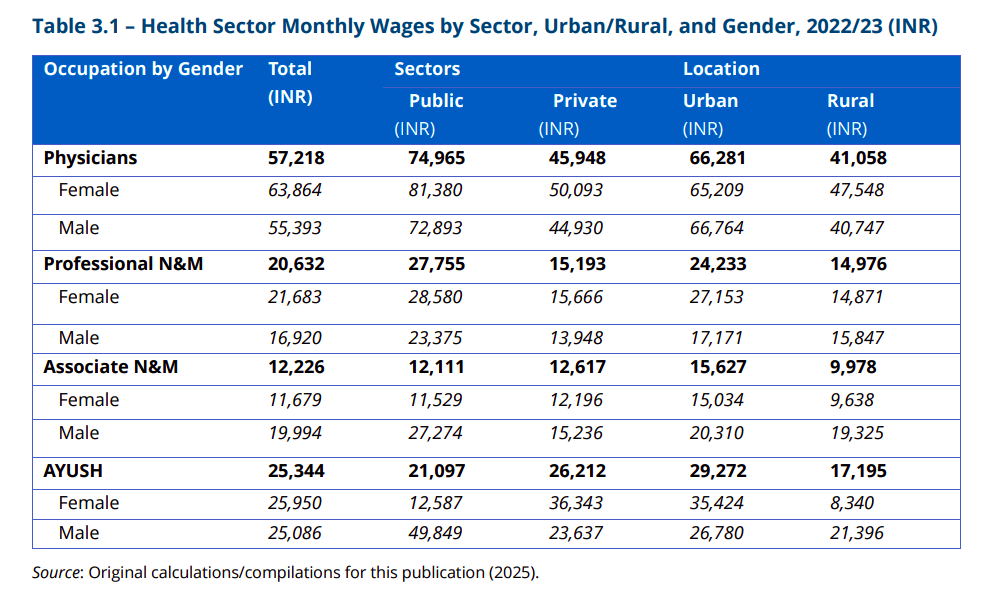

There are also sharp differences between the two sectors. Public sector workers earn more — doctors make about 63% more in government jobs than private ones, and nurses about 83% more. But private sector workers put in longer hours. Associate nurses in private hospitals, for example, work eight hours more per week than their public-sector counterparts.

So India’s healthcare labour market isn’t one system. It’s really two parallel systems, with different incentives and challenges.

Wages, migration, and the global pull

Let’s talk money. How much do healthcare workers actually earn?

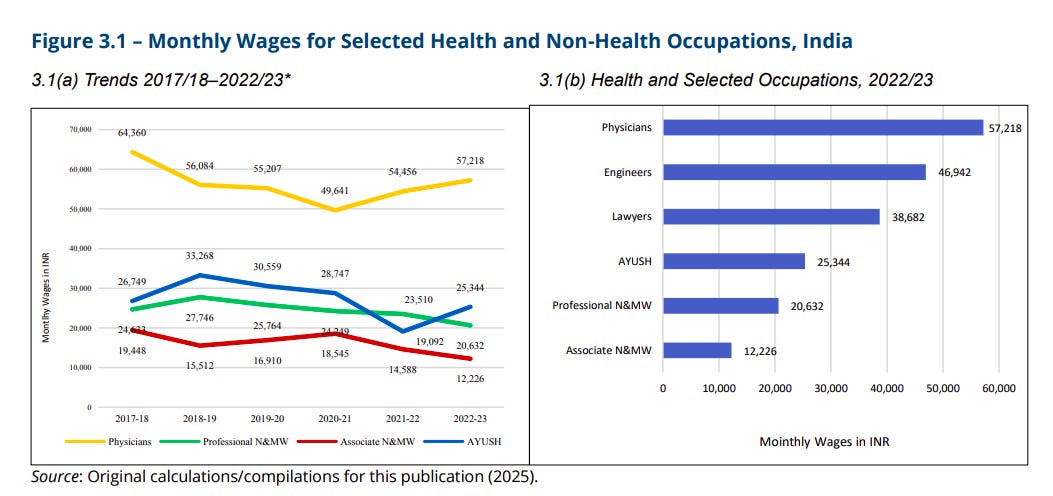

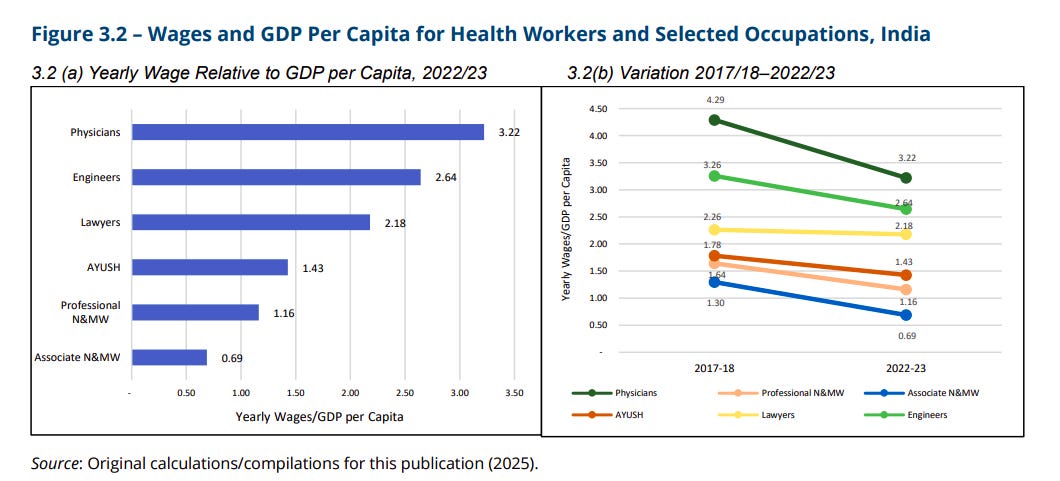

Doctors in India earn about 3.2 times the country’s GDP per capita. Nurses and AYUSH practitioners earn slightly above GDP per capita, while associate nurses earn less than that benchmark.

But wages have been falling in real terms since 2017. Doctors have seen an 11% drop, nurses around 20%, and associate nurses as much as 37%. Inflation, oversupply in some areas, and shifts in financing models are all factors.

And here’s an interesting finding: higher pay doesn’t necessarily lead to more work. In fact, when healthcare workers get a 10% wage bump, they slightly reduce their working hours. Many are already working about 46 hours a week—far above the national average—so when their income rises, they prefer to take a little more time off.

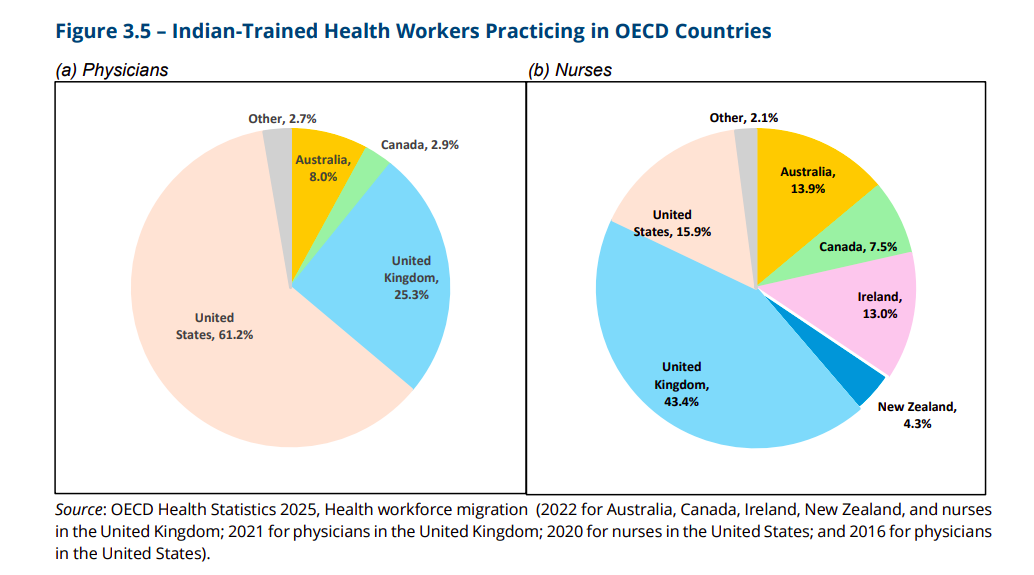

Another force shaping the market is migration. Around 75,000 Indian doctors and over a lakh Indian nurses are currently working in OECD countries like the US, UK, Canada, and Australia. That’s about 7% of all Indian doctors and 11% of nurses. It’s a huge brain drain—India bears the cost of training, but richer countries benefit from their skills.

Women in healthcare

Now let’s talk about something that’s both a success story and a massive missed opportunity: women in healthcare. Women make up 63% of India’s healthcare workforce, compared to just 36% in the overall economy. Medical training is a powerful driver here: it increases women’s probability of working by nearly 25 percentage points, compared to 20 for men.

In most developed countries, women make up 60–70% of the healthcare workforce. India is already in that range — even though its overall female participation rate is among the lowest globally. In that sense, healthcare is a rare sector where India is closer to global norms.

But it doesn’t mean there are no challenges. Women in healthcare earn about 30% less than men. Among nurses, the gap is 20–23%. Female doctors actually earn slightly more than men, likely because they are concentrated in higher-paying specialties and cities. But overall, India’s gender gap is larger than the 15–20% seen in OECD countries.

Household responsibilities also weigh heavily. Each additional family member reduces a woman’s likelihood of working by about 0.7 percentage points. Over a third of women with medical degrees are out of the workforce altogether. Many drop out because of childcare and eldercare duties, and few employers provide the support needed to balance both.

The missed opportunity is massive. If India could close even half the gender gap in healthcare, the World Bank estimates it could create 40–60 lakh additional quality jobs for women in the next decade. That’s more than the entire healthcare workforce of Thailand or Malaysia.

Job quality

So what’s it actually like to work in Indian healthcare?

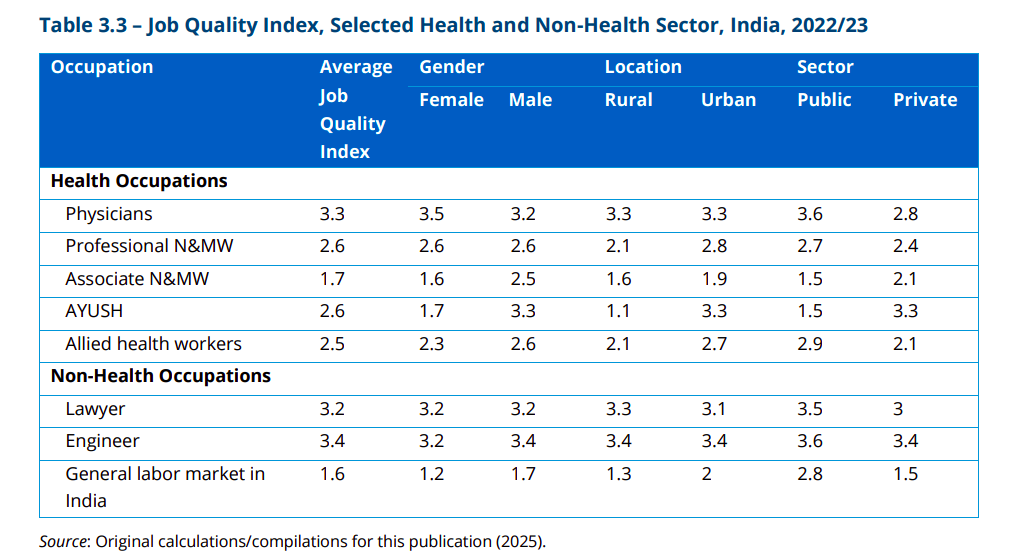

Not all healthcare jobs are equal. The World Bank created a Job Quality Index based on four things: income above the poverty line, access to benefits, job stability, and reasonable working hours.

Doctors score highest, at 3.3 out of 4 — comparable to lawyers and engineers. Professional nurses score 2.6. Associate nurses just 1.7. In fact, nearly half of them don’t earn enough to keep their families above the poverty line.

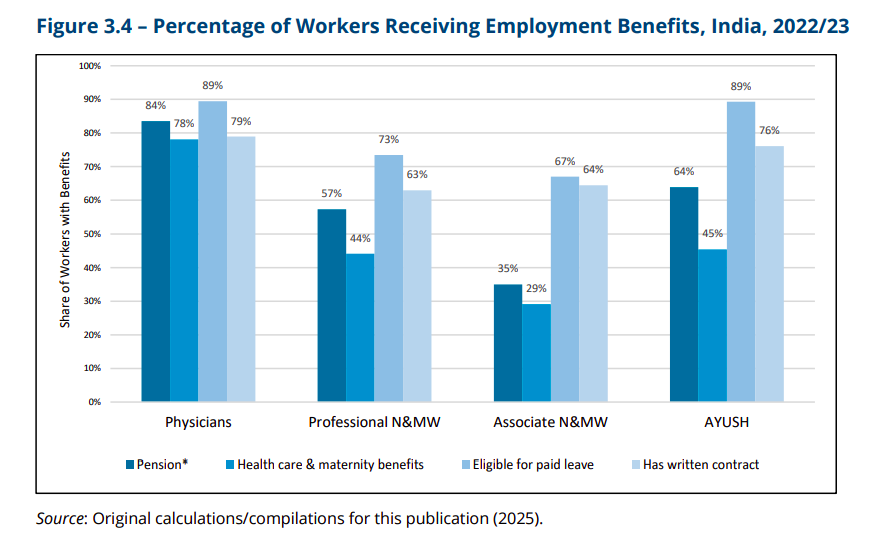

Benefits show the same divide. 84% of doctors have pensions, compared to only 35% of associate nurses. Healthcare and maternity benefits reach most doctors but less than a third of associate nurses. And remember, these are the workers staffing rural clinics and health centres. If they’re insecure and underpaid, the entire system feels the strain.

Looking ahead

Let’s talk about the future. The World Bank lays out three possible futures for India’s healthcare workforce by 2035, depending on the benchmark.

Scenario 1: WHO benchmark.

The WHO says a country needs at least 44.5 health workers for every 10,000 people to provide basic healthcare services. If India pushes toward that level, it will still face a shortage of somewhere between 22 and 33 lakh workers in 2025–26, narrowing to about 80,000 to 2.8 lakh by 2035. In other words, India will come close, but not fully close the gap.

Scenario 2: Median SDG threshold

This is the middle-of-the-road target used for tracking progress on health-related Sustainable Development Goals. The requirement here is just 13.7 workers per 10,000 people — much lower than the WHO’s standard. Under this scenario, India actually has a surplus. By 2025, it would have over 20 lakh more workers than needed, and by 2035 the surplus could rise to 44 lakh. On paper, that looks comfortable, but it also means the threshold is so low that even meeting it may not guarantee good quality care.

Scenario 3: Top-tier outcomes.

If India decides it wants to match the best-performing countries and targets 92.7 workers per 10,000 people — the 75th percentile of global health systems — the challenge becomes massive. India would need between 90 lakh and 1.02 crore additional workers by 2025, with the gap shrinking only slightly to around 74 lakh by 2035. That’s an ambitious goal, but it reflects what’s really needed if India wants world-class healthcare.

Now here’s where things get interesting: the demand side of the equation. Supply is one thing, but how many workers can the economy actually employ? The study estimates that India’s healthcare system will demand about 20 lakh additional workers by 2025, growing to 67 lakh by 2035. That’s driven by rising health spending, more insurance coverage through schemes like Ayushman Bharat and PM-JAY, and higher expectations from patients.

For now, supply and demand are gradually converging. India currently has a small surplus, but as population ages and demand for care rises, that cushion will shrink. By 2030, the surplus could vanish, and by 2035, India may even face a small shortfall of 13,000 to 2.15 lakh workers.

The encouraging part is that training capacity is expanding in parallel. Medical colleges and nursing schools are producing more graduates than ever, and government programs are increasing demand in a structured way. But that balance will only hold if reforms keep pace — if the workforce is deployed efficiently, if rural areas are staffed, and if job quality improves so people stay in the profession.

Conclusion

To wrap this up.

India’s healthcare workforce is huge, fast-growing, and full of potential. But it’s also unevenly distributed, under strain in rural areas, and weighed down by training and quality gaps.

Doctors and nurses in cities are doing relatively well. Associate nurses in villages often struggle to make ends meet. Women make up the majority of workers but face large pay gaps and limited support. And thousands of trained professionals continue to migrate abroad each year.

The lesson is clear. Fixing India’s healthcare system isn’t just about training more doctors. It’s about creating the right incentives, strengthening regulation, and improving working conditions so people not only enter the profession but also stay and thrive in it.

Tidbits:

Berkshire Hathaway is buying Occidental Petroleum’s chemical arm, OxyChem, for $9.7 billion. The unit makes essentials like chlorine, vinyl chloride, and calcium chloride — chemicals used everywhere from water treatment to road safety. Many see this as potentially Warren Buffett’s last big acquisition.

Source: Economic Times

Abu Dhabi’s International Holding Company, through its arm Avenir Investment RSC, is putting in about ₹8,850 crore — nearly $1 billion — to pick up a 43.5% stake in NBFC Sammaan Capital. The investment is through a mix of shares and warrants at ₹139 each. With this, IHC becomes a key promoter of the lender, and under Indian rules, must also make an open offer for another 26% stake.

Source: Money Control

The U.S. government has entered a shutdown after Congress failed to agree on a funding bill. That means most federal operations have stopped, new spending is on hold, and non-essential workers have been sent home without pay. Essential services like defense and air traffic control are still running, but many government employees now face delayed salaries.

Such shutdowns usually come from political deadlock over how the budget should be spent — and they often weigh on both the economy and basic public services.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Bhuvan

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

In the article, you mentioned there are 2.5 lakh AYUSH Practitioners in India, but official data says 7.5 lakh. https://ddindia.co.in/2025/04/13-86-lakh-registered-allopathic-doctors-7-51-lakh-practitioners-in-ayush-system-centre/

As usual, very insightful and detailed. A query though... is it true that NBFCs cannot accept deposits?

"So how do NBFCs actually make money? Their model is simple. They borrow funds—usually through bonds, debentures, or bank loans, since they can’t accept customer deposits."