India plugs into China’s batteries

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India makes room for Chinese batteries

The fictional revenues of Seacoast

India makes room for Chinese batteries

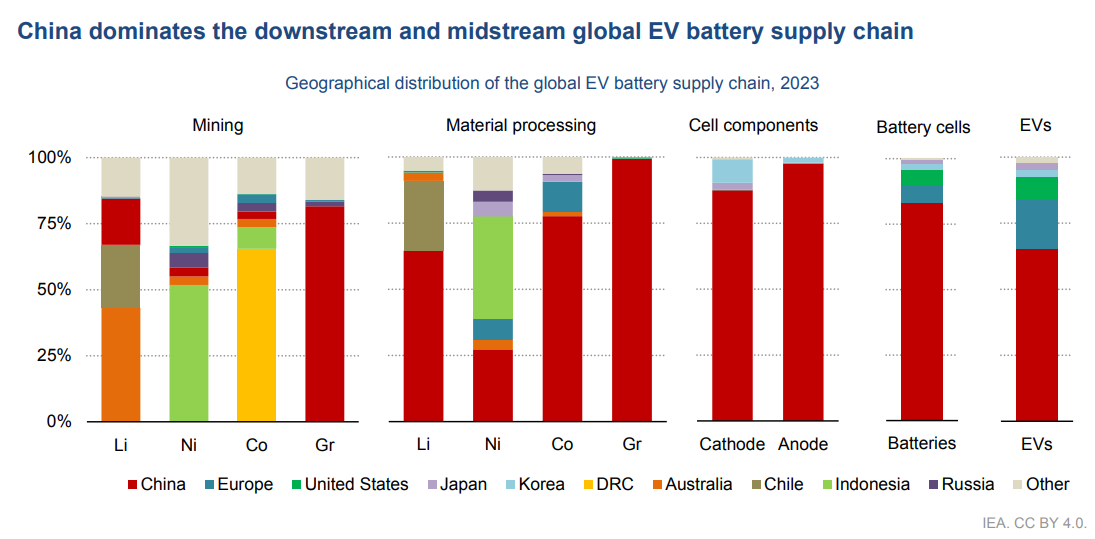

Previously, on The Daily Brief, we explored how lithium has emerged as the ‘metal of the century’, powering everything from smartphones to electric vehicles. This rush has fundamentally reshaped global supply chains, with a single country dominating the world’s ecosystem: China.

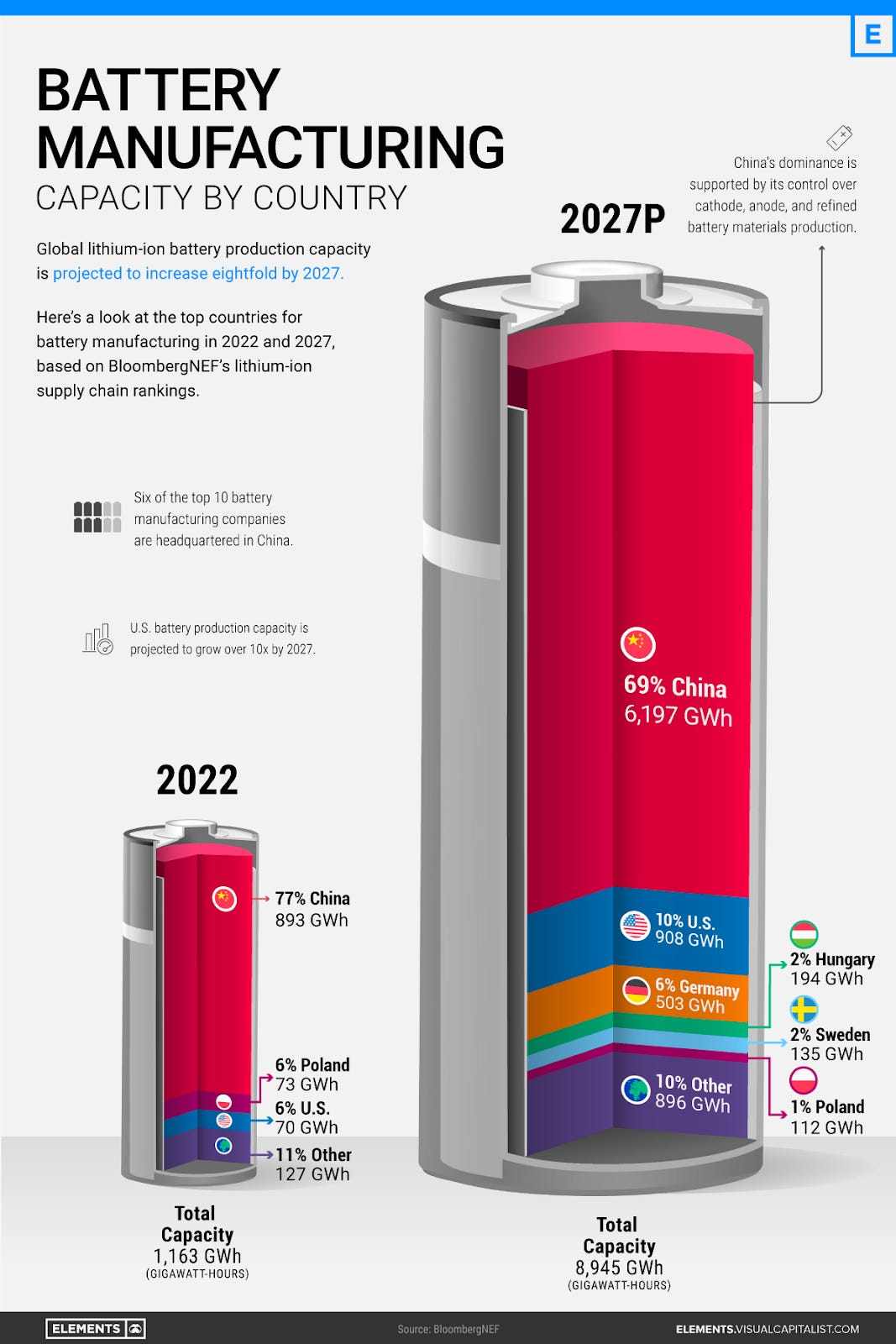

China processes more than 60% of the world’s lithium — and controls over 77% of global lithium-ion battery production.

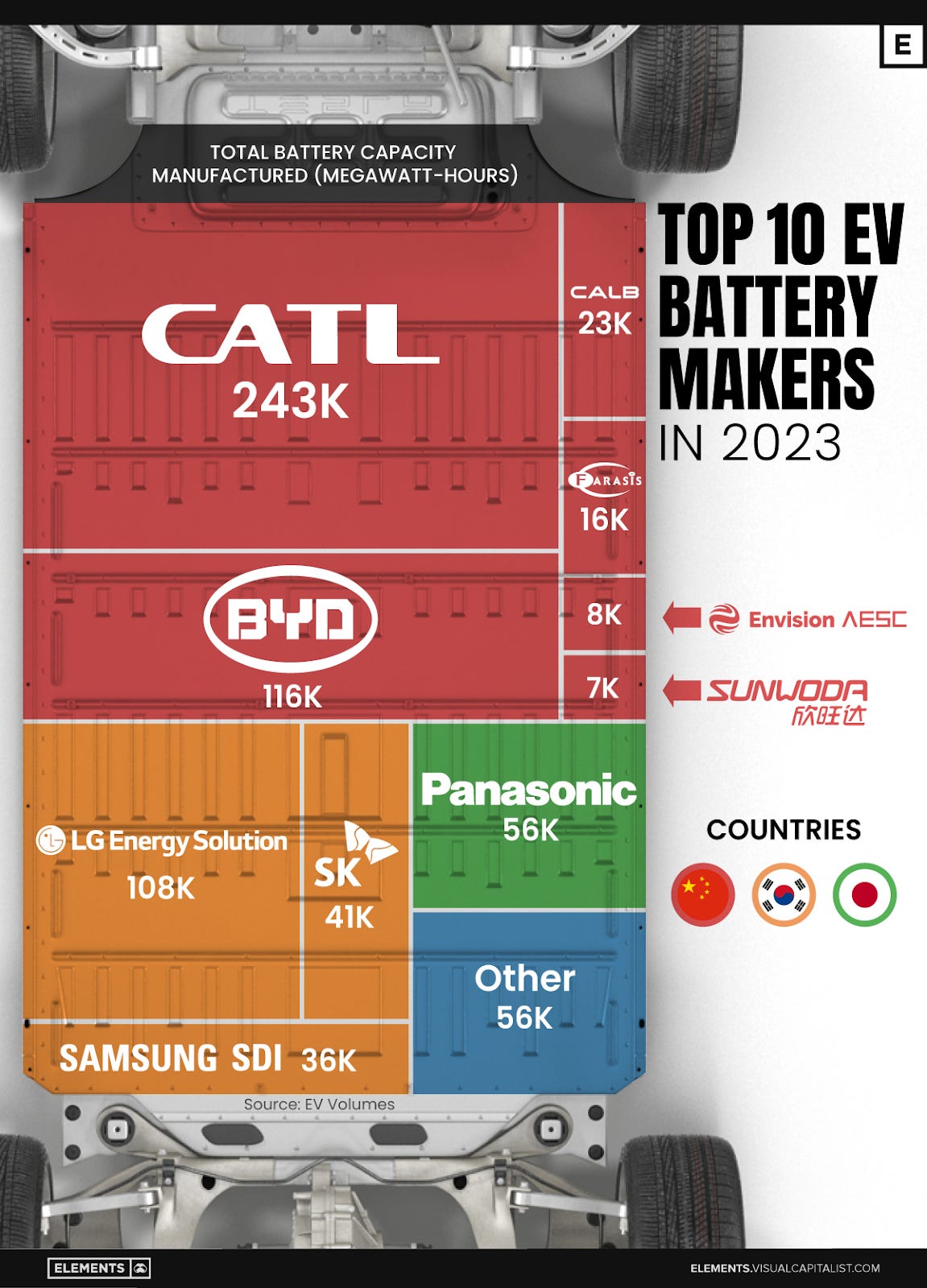

The three largest battery manufacturers from China — CATL, BYD, and CALB Group — collectively command a massive share of the global battery market. In fact, CATL alone has captured over 35% of the global battery market, with production capacity exceeding 500 GWh annually.

But we’ve talked about batteries enough, over here. Why are we bringing all this up again, today? Well, because India is now turning to China for its battery-making expertise. Ashok Leyland, one of India’s largest makers of commercial vehicles, just inked a long-horizon deal with China’s CALB to climb that ladder.

And it’s not just them — they’re just one part of a larger trend.

Here’s how the deal looks like

Here’s what Ashok Leyland and CALB have agreed to: CALB will supply lithium-ion cells while Ashok Leyland learns to assemble them into battery packs. Gradually, Ashok Leyland shall build out its capability to design and manufacture those cells in India. The partnership involves over ₹5,000 crore ($600 million) in planned investments over the next 7-10 years.

The deal is practically a technology apprenticeship. At first, CALB shall ship cells to India, as Ashok Leyland’s engineers learn critical processes — like thermal management, battery management software integration, or pack design — under Chinese guidance. Ideally, over the next five years, as Indian teams absorb this expertise, they’ll transition towards learning how to make those cells indigenously.

The deal is a massive win for Ashok Leyland. While it has been betting big on electric vehicles, those plans have a severe shortcoming — batteries, which makes up much of the value of an EV — is something it has no expertise in. This deal plugs in that critical gap, giving it access to proven technology and know-how.

Meanwhile, for CALB — a distant third in China’s battery race — it opens India’s massive emerging market. As we noted recently, the country has a severe overcapacity problem, and that is also true of batteries. Such a massive source of demand, in the midst of a massive battle for survival, could be exactly what CALB needs.

The partnership targets 4-6 GWh of battery demand from Ashok Leyland’s own vehicles over the next 4-5 years. But there’s also a bigger prize in their sights: supplying other automakers, across vehicle segments, and perhaps cracking grid-scale storage as well, all within 2-3 years.

From the statements we have seen, what Ashok Leyland really prizes about this deal isn’t access to batteries, but knowing how to put a battery together. In the words of the company’s CEO, Shenu Agarwal, “process is even more important than technology in the beginning.“ That is a massive moat that only leading Chinese companies currently have, which Ashok Leyland wants a piece of.

How far will CALB go in giving them this crucial information? We aren’t sure. Mr. Agarwal himself says that CALB will only have a “limited but supportive role” in Ashok Leyland’s eventual goals of innovation and R&D in batteries.

Notably, the details of future phases of this partnership haven’t been chalked out yet. As Mr. Agarwal cryptically said, they plan to “do whatever is permissible by the law of the land”. It’s an interesting statement — and while we aren’t completely sure of what it means, it seems to us that they’re afraid that geopolitical issues could complicate things.

But maybe that’s a risk worth taking.

It’s not just Ashok Leyland

This is part of a larger pattern. Many Indian companies are seeking the expertise of Chinese battery makers for their own plans — a trend that’s gaining momentum as the relationship between our two countries is starting to thaw.

Exide, which makes most of India’s old-style lead batteries, signed with China’s SVOLT to build a big lithium-ion factory with their technology. Similarly, Amara Raja Batteries has tied up with Gotion High-Tech from China for lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery know-how and access to Gotion’s supply chain.

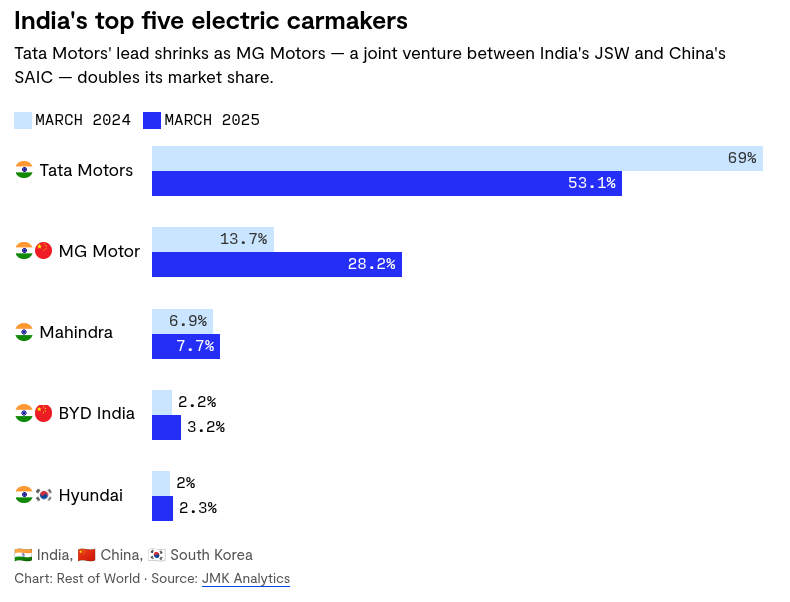

This is one chapter in a wider push, as India’s auto industry reaches out to China for its deep EV expertise. The marquee deal here, of course, is JSW’s joint venture with SAIC, which created MG Motor India — a deal that has taken our EV market by storm. MG’s share doubled over the last year, and its Windsor model has become the country’s top-selling EV.

But batteries are where China’s expertise really shines. And it’s something we’ll need a lot of, if we hope to make a successful green transition.

What India can already do

A lithium-ion battery system has four main components: cells (65% of cost), battery pack assembly (15%), battery management system (15%), and housing/cooling systems (5%).

India has some expertise in all of the lower-value parts of the chain. Companies like Exide, Amara Raja, Coslight India, and dozens of smaller players can assemble cells into battery packs, integrate cooling systems, and develop battery management software.

The one thing we don’t yet have expertise in, however, is also the most crucial: cell manufacturing. This is an expensive, technically challenging step. Setting up a minimum viable 5 GWh cell production facility requires approximately ₹1,000 crore in capital expenditure.

More critically, however, it demands expertise, which India sorely lacks. To make a cell, you need to master a variety of hard processes: from preparing electrodes, to coating them with the right chemicals, to putting it all together, to activating the cell, and more. We’ve talked about some of this before. Every step requires specialized equipment, process control, and technical knowledge — which Chinese companies have refined over decades.

Now, India does have some emerging capabilities. Epsilon Advanced Materials has started manufacturing graphite precursor material for anodes. TDSG — a Toshiba-Denso-Suzuki joint venture — began commercial cell production in December 2020.

The Indian government also has a PLI scheme, aimed at bridging the remaining gaps. Ten companies submitted bids for approximately 130 GWh capacity, including Reliance, Ola Electric, Lucas-TVS, Mahindra, Amara Raja, and Exide. To qualify, they’re required to set up 5 GWh battery facilities, where they’ll eventually add 60% of the value.

That said, we have a very long way to go. Currently, India imports virtually all lithium-ion cells — with 60-65% of battery pack components coming from China. We had just 6.7 GWh of commissioned lithium-ion cell production capacity as of 2023, compared to China’s several thousand GWh. Even with Chinese partnerships and government support, most experts believe India will take at least 5-7 years to achieve meaningful scale in cell manufacturing.

Our dependency for raw materials will persist for even longer. While we might have some domestic lithium reserves — with recently discovered sites potentially yielding an estimated 5.9 million tonnes — we’re years away from actually making use of it. For now, we must import nearly all lithium carbonate, cobalt, nickel, and other critical battery materials. China, meanwhile, controls over 80% of global lithium processing and 90% of rare earth element refining.

Why we need China

India’s electric vehicle targets – 30% of private cars, 70% of commercial vehicles, and 80% of two-wheelers to be electric by 2030 – necessitate massive battery capacity. Current projections suggest India will need 116 GWh of annual battery capacity by 2030, with EVs accounting for roughly 90% of demand.

Right now, there are serious barriers we need to cross before we can meet that demand. To meaningfully plug these gaps, partnering with China is arguably our only option.

China has the know-how that we desperately need. Their manufacturing playbooks have been refined over years. Chinese firms have perfected factory layouts, equipment specifications, quality control protocols, and supply chain integration. Without them, Indian companies will take years to develop that knowledge independently.

Moreover, they have market access and scale. A Chinese partner can link Indian companies to established supply chains for everything from cathodes, to anodes, to separators, to electrolytes. Their expertise can also point to how we can achieve the scale of production needed for cost competitiveness. Most Indian projects, today, are starting with 1-5 GWh pilot facilities, but economic efficiency requires much larger scale.

The strategic calculus

There are, of course, risks in partnering with China. It has barely been five years since the Galwan clash, and we should be under no illusions — those tensions could re-surface at the drop of a hat. We’ve written about this complex dynamic before.

But ultimately, these battery partnerships reflect a calculated strategic choice. India is choosing to accept the risks which come with integrating into Chinese supply chains. Complete self-reliance is not a viable option for us. If we try and do this alone, it shall severely constrain our electric transition. As an expert told Rest of the world: “Without Chinese tech, India would face supply shortages, delayed rollouts, and reduced product diversity.“

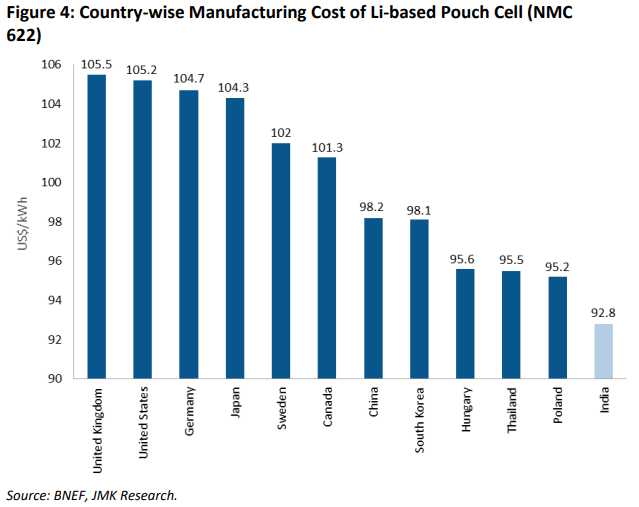

If India manages to develop this expertise, we could, over time, even find a comparative advantage here in terms of our cost competitiveness. Analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance indicates India could, with our cheap labour force, become an important lowest-cost location for lithium-ion cell manufacturing globally, with projected costs of $92.8/kWh compared to $98.2/kWh in China.

Meanwhile, such partnerships also reveal something else: China is interested in India’s market. With domestic EV demand maturing, India represents massive growth potential — our electric vehicle sales are expected to increase 66% in 2024, reaching 30% of auto sales by 2030. For Chinese companies, technology partnerships provide market access while complying with India’s foreign investment restrictions.

Ultimately, India’s battery partnerships with China represent a simple truth: while our countries don’t always see eye-to-eye, there are important opportunities for Indian and Chinese businesses that are willing to look across the border. If the partnership between Ashok Leyland and CALB succeeds, it could push many others to search for those opportunities.

The fictional revenues of Seacoast

On paper, Seacoast Shipping Services Limited (Seacoast) seemed like an immensely successful company. Its business — shipping and logistics — yielded exceptional returns. Its revenues were climbing at a blistering pace. From barely ₹50 lakh in FY 2020, they had grown to a remarkable ₹430 crore by FY 2023.

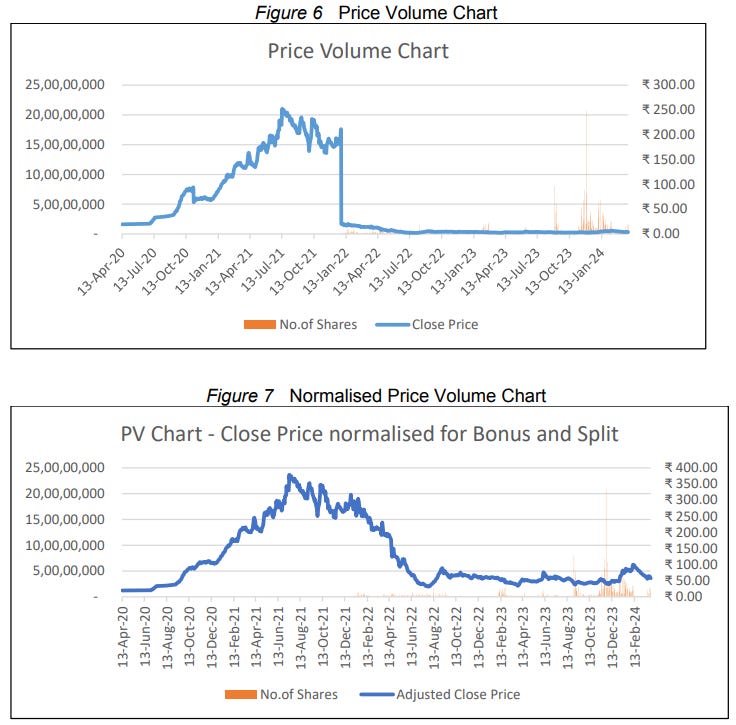

The company was listed on BSE, and its rapidly climbing revenues sent its stock price soaring. If you would have bought shares of the company in July 2020 and held on for a little over a year, you would have made returns of 2,000%. Its promoter, meanwhile, was giving interviews to major brokerages. It was the kind of company that exemplified the madness around small cap stocks in the COVID era.

Something didn’t seem to fit, however. Seacoast ran a multi-crore rupee business, but it seemed to have no property. Nor did it have any inventory. It flipped from business to business, jumping from shipping to agricultural sales. And all the company’s value, on paper, came just from trade receivables that promised to hit its accounts some day in the future.

It all seemed terribly unusual. And so, SEBI launched an investigation into the company.

Seacoast’s cash flow-less transactions

There’s a reason SEBI is so incredibly touchy about how companies report their finances.

When you invest in a publicly traded company, you’re essentially flying blind. You don’t sit on its board; you don’t track the daily cash register, and you don’t see containers being loaded at the port. You have a single window into how the company is doing: its financial statements. If those numbers are misstated, as an investor, you functionally have no defence against being defrauded.

From the looks of it, that’s precisely what was happening here, to legions of retail investors that trusted the Seacoast’s rapid on-paper rise.

SEBI, thankfully, has a few more tools than the average investor. It could access other records — like GST records, or bank account statements. Those seemed to convey a completely different picture.

Here’s one example: if Seacoast’s annual reports were to be believed, the company was making large raw material purchases every year, paying out hundreds of crores to its suppliers every year. Funnily enough, however, when SEBI looked at the bank accounts of the company, only one-third of that money actually seemed to leave its accounts.

What was really happening?

As the cracks in Seacoast’s reported activity became apparent, SEBI started digging through years of records. The more it dug, the more misstatements it found — in what seems like one of the most egregious cases of financial misreporting by a micro-cap company in recent years.

In FY 2021, for instance, Seacoast’s biggest customer was a Singapore-based company called Bimstar Holdings. 86% of Seacoast’s sales — over ₹81 crore — came from the company. Only, the company’s bank accounts held no trace of these transactions. Bimstar would later be struck off from Singapore’s corporate records as well.

Similarly, Seacoast claimed to have made over ₹73 crore of “purchases” from Dubai-based Allianz Bulk Carriers. Once again, no money seemed to flow out of Seacoast’s accounts.

This pattern would keep repeating itself. In FY 2022, for instance, Seacoast had major dealings with two Singapore-based companies, Real Tex and Safe Cargo. It had bought ₹94.06 crore worth of goods from Safe Cargo, and sold ₹60.56 crore worth of goods to Real Tex. It had invoices for all of it. But there was no hint of any of this in its bank statements. Both companies, it soon turned out, were incorporated on the same day, with the same Singapore address. On paper, they both began with SGD 5,000 of capital, and have never filed a single set of annual returns in their life.

The hundreds of crores of business activity, it seemed, were all based on lies.

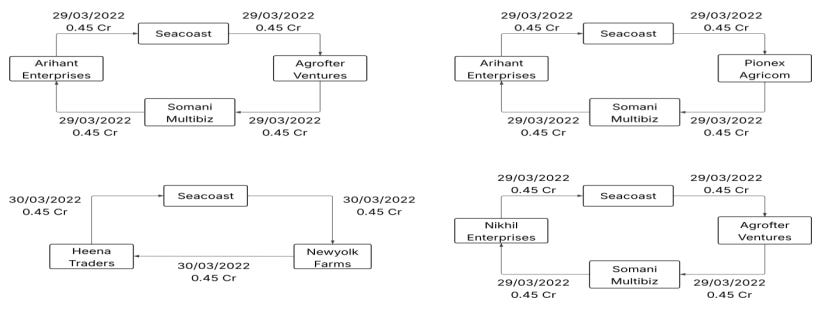

Occasionally, it seemed, some money would actually change hands. But that, too, seemed suspicious. In FY 2022, for instance, Seacoast purchased ₹20 crore worth of agricultural products from eight entities, which it sold onwards to ten entities, booking ₹21 crore in sales. All of that was money that actually moved in and out of its accounts. It looked legitimate.

On closer inspection, though, SEBI realised that its counterparties were all related. The money it paid for those “purchases” would bounce through a series of companies before hitting its own accounts.

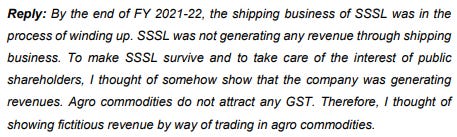

Why was a shipping company suddenly trading agricultural products, by the way? As its promoter admitted, trades in agricultural commodities didn’t attract GST, and therefore weren’t recorded by the government. That, he thought, would protect the company from further scrutiny.

Increasingly, one was driven to wonder: was this a real business at all? Was there any activity behind this facade? This didn’t look like a business that was padding its books. This seemed like a company that, behind those cooked books, was completely hollow.

The company owned nothing. Most of what it called “assets” were mere promises — trade receivables from companies tied to fictitious transactions, In FY 2022, for instance, 99.7% of its assets were just receivables and advances. In FY 2023, 98.3% of its assets were receivables. This was all “wealth” only on paper. Nothing actually existed.

Entire quarters seemed to go by without genuine activity. In the December quarter of FY 2023, for instance, the company’s books showed ₹28 crore in sales. Its GST returns, however, showed no transactions at all.

Eventually, the company’s promoter himself confessed: three-fourths of all the “business activity” the company had claimed in FY 2021 and 2022 was fictitious. From that point onwards, all the activity they reported was fictitious.

The promoters’ take

But why do this? What were all these inflated, non-existent transactions in service of?

Two words: stock prices.

That was the holy grail the company’s promoters were chasing. If they could push the price of their stock high enough, they could convert those paper transactions into real money. And it all seemed to go to plan. As the company inflated its financials, its stock price rose — hitting its peak midway through 2021.

Meanwhile, the company had been handing shares over to its promoters through preferential allotments. In FY 2021, Seacoast supposedly bought the business of its promoter’s HUF, valued at ₹22.73 crore, allotting 1.5 crore shares to him in return. Only, the company didn’t seem to acquire any assets in this transfer. In its books, the company claimed a cash inflow for that amount, but no cash actually seems to come in either. There was no proof, in fact, that the company got anything at all. Those shares, in effect, were given to the promoter for free.

As the company’s share price went up, a large number of retail investors started buying into the stock. At its height, the company had 2.5 lakh public shareholders. Meanwhile, the company’s promoters started dumping their shares onto the market. From a peak of 74% in September 2020, their shareholding fell to just 0.04% by the end of 2023. Over-enthusiastic retail shareholders, it seemed, were stuck holding the entirety of a non-existent company.

Their biggest take, however, came when the company raised public money. Midway through 2023, Seacoast announced a rights issue, supposedly to shore up its working capital. The issue brought in nearly ₹50 crores from the market. Of that, ₹5 crores went into paying off a credit facility the company had taken from IndusInd Bank — which was then used to fund all of the company’s fraudulent transactions.

The rest of that amount simply disappeared into a web of companies: 16 entities, to be specific, which then transferred it onwards to another 75 second-layer entities.

When SEBI questioned them, the company’s promoters claimed that their son had been kidnapped, and the money from the rights issue went into paying off his ransom. Is that true? Well, all we know is that there’s no police complaint that validates this.

SEBI cracks down

From when SEBI first issued its notice to the company, around a year ago, it has meandered around the system — briefly landing up before SAT.

But now, SEBI has officially cracked down on the company. In its final order, released on Wednesday, it found that a large part of the company’s business was not genuine, and that its promoters had defrauded the company.

And so, the regulator has handed out public market bans to Seacoast, its promoters, and a variety of other officials. Seacoast has also been fined ₹50 lakh, while its promoters and key officials have been handed additional penalties worth a total of nearly ₹1.5 crore. Promoter Manish Shah has also been asked to hand over the ~₹48 crore that he earned from this fraud, along with interest of 12%.

This is just a single case. But it has lessons that are universal.

When markets run hot, it’s tempting to invest out of sheer FOMO, hunting for small- and micro-cap companies. That’s dangerous. Not because there are no small companies which are worth your investment — there absolutely are — but because there could be fly-by-night operators that are reeling you in with stories that are too good to be true, just so they can saddle you with toxic shares which represent nothing.

There are ways to spot those companies. But that requires diligence. You need to look beyond top- and bottomline figures, and understand what’s really happening. You need to apply your own judgement to what a company shows as assets, or cash flows, and ask yourself if any of that actually makes sense. You need to see if the company has corporate governance institutions robust enough to weed out any wrongdoing. You need to look behind the hype, and understand what you’re actually buying.

When times are good, it’s easy to imagine you’re too smart to be taken for a ride. But chances are, that’s what Seacoast’s 2.5 lakh retail shareholders thought as well.

Tidbits

India’s private sector expansion seems to be cooling down. HSBC’s India PMI fell from a multi-year high of 63.2 in August to 61.9 in September, with both manufacturing and services output dipping. Job creation slowed down a little from August as well, with only 3% of manufacturers and 5% of service providers reporting an increase in payroll. However, August marked the second-sharpest expansion rate in the last 2 years. (Source)

The Indian government is planning to create an industrial policy to promote homegrown consulting firms, and reduce dependence on the “Big 4” firms: EY, Deloitte, PwC, and KPMG. Policy measures include easing advertising rules for CAs and lawyers, allowing the creation of multi-disciplinary partnership firms, and boosting the capacity of existing institutions like ICAI and ICSI. (Source)

As per Bloomberg, Intel is reportedly seeking an investment from Apple. The talks are still in their early stages. This comes right after investments from the US government, NVIDIA and SoftBank have seemed to save the failing chipmaker from complete ruin. Once a customer of Intel, Apple switched to using in-house chips in its Macbooks. (Source)

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

📚Join our book club

We’ve started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we’d love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

This is a great read. The Ashok Leyland–CALB deal shows why India still needs China’s expertise for batteries. There are risks, but learning from them is the fastest way to build domestic skills. Over time, India could even become cost-competitive in battery production.

Really insightful piece — especially the part on India learning battery tech “the hard way” through partnerships rather than isolation.

But the real question now is how India ensures genuine technology transfer — not just assembly rights. CALB’s entry is useful, but we must build upstream capability too: cell chemistry R&D, refining, and recycling. Otherwise, we’ll end up financing China’s scale rather than building our own.

A balanced path would be learning from China’s speed, while aligning with Japan, Korea, and Europe for diversification.

Because strategic dependence in the energy transition can be as risky as dependence in oil once was.

India’s EV dream will truly take off when we own the chemistry, not just the factory. ⚡🇮🇳