How do Indian securities regulations and market infrastructure institutions compare to the US?

Investing in India #7

Investing requires healthy markets, which in turn depend on fair regulations and strong market infrastructure institutions. While I’m confident India has these in place, I’ve often wondered about the off-hand comments fund managers make about the reliability of financial statements, the absence of class-action lawsuits, and even Nithin Kamath’s observations on how Indian markets are structured differently.

This led me to a basic question: how does India stack up on these fronts? More specifically, how do we compare with the largest market in the world—the US?

To explore this, I spoke with Sandeep Parekh, who has worked in both markets. Sandeep is the Managing Partner of FinSec Law Advisors and a former Executive Director and head of the Legal Affairs and Enforcement departments at the Securities and Exchange Board of India. He holds an LL.M. in Securities and Financial Regulations from Georgetown University and is a member of both the New York Bar and the US Supreme Court Bar. Having worked with law firms in Delhi, Mumbai, and Washington, D.C., Sandeep’s core focus is securities regulations, investment regulations, corporate governance, and public policy. He is also the author of Fraud, Manipulation and Insider Trading in the Indian Securities Markets, which offers a comprehensive and critical analysis of securities fraud and insider trading regulations.

Background

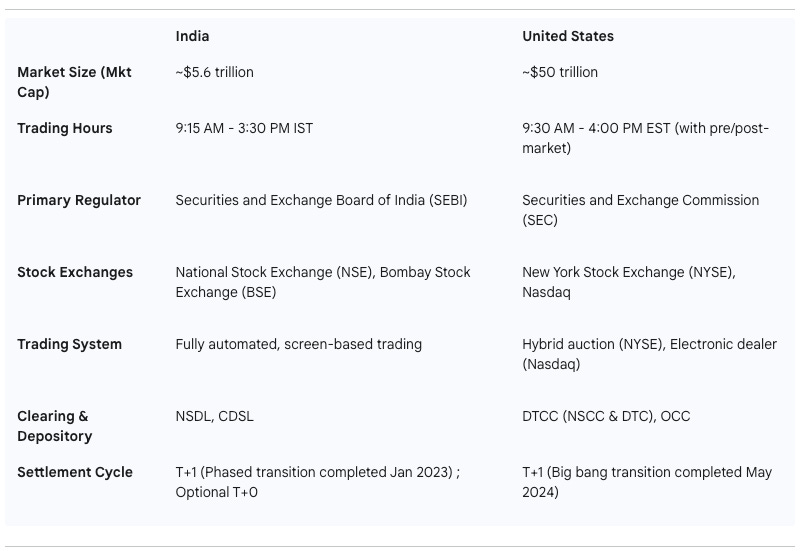

The U.S. regulatory model is built on a system of oversight in which the SEC empowers and supervises self-regulatory organizations (SROs). These SROs—including stock exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and Nasdaq, as well as entities like the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) and the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC)—are responsible for creating and enforcing industry rules for their members. The SEC reviews and approves these rules, conducts inspections, and maintains ultimate authority, while delegating day-to-day oversight. This division of labor allows the SEC to concentrate on systemic risks and broad policy.

India, in contrast, follows a more centralized and direct model. SEBI regulates and oversees market infrastructure institutions (MIIs) and other intermediaries itself. This approach ensures clear accountability, but it can also create administrative bottlenecks.

The U.S. market structure has evolved into a hybrid system. The NYSE operates as a hybrid auction market that, while now heavily electronic, still maintains a physical trading floor and designated market makers known as “specialists.” Nasdaq, on the other hand, is a fully electronic dealer market where competing market makers post two-sided quotes. This historical divergence explains why the NYSE is often associated with large, stable blue-chip companies, while Nasdaq has become synonymous with younger, growth-oriented technology firms.

India’s exchanges, by contrast, were designed as fully electronic platforms from the start. By bypassing the inefficiencies of physical trading floors, they enjoyed a structural advantage that enabled faster growth, lower costs, and greater efficiency.

Podcast summary - by Sandeep Parekh

India’s rule-based securities laws vs. the U.S. principle-based approach

When it comes to securities regulation, India and the United States present a striking contrast in style, pace, and philosophy. Both run mature capital markets that attract billions in investment, but their approaches to lawmaking, disclosure, and infrastructure reveal very different regulatory DNA.

India has historically been rule-bound, drafting voluminous regulations that attempt to anticipate every possible scenario. The U.S., by contrast, leans toward a principle-based model, setting broad obligations and relying on courts and enforcement actions to define boundaries over time. This difference shows up everywhere—from the thickness of a prospectus to the speed of market settlements.

See also: Economic Times piece on the two systems and their treatment of fraud.

From merit to disclosure: A timeline divergence

Until 1988, India operated under a merit-based regime overseen by the Controller of Capital Issues (CCI). Regulators decided whether an issue was “good” for investors by scrutinizing its pricing, timing, and structure. While intended to protect investors, this approach delayed capital raising and stifled innovation.

That year, India shifted to a disclosure-based system. Issuers now had to provide exhaustive disclosures, while investors were expected to judge quality and value themselves—bringing India in line with global practice.

The U.S. had made this transition decades earlier. The Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, passed in the wake of the Great Depression and Wall Street scandals, laid the foundation for disclosure-based regulation under the newly created SEC. In effect, what India achieved in 1988, the U.S. had already implemented more than half a century earlier.

Rule-making vs. case law: How the law evolves

India responds to crises and gaps with speed and detail. Each event spawns new, often highly prescriptive regulations, leading to overlaps, contradictions, and regulatory clutter. Prospectuses in India now run 300–400 pages, packed with disclosures, risks, and checklists. While this level of detail improves transparency, it can overwhelm investors and raise compliance costs for issuers.

The U.S. takes a different path. It sets broad principles and lets courts refine them over time. Insider trading law, for instance, is not found in a single statute but has been developed through decades of judicial interpretation of general antifraud provisions. This system offers flexibility but can leave uncertainty until case law matures.

In short, India is impatient, drafting new rules quickly, while the U.S. is patient, letting precedent evolve. Both have trade-offs: India risks clutter and over-deterrence, while the U.S. risks ambiguity and uneven enforcement.

The expanding prospectus: Information or obfuscation?

In India, the Red Herring Prospectus has become a 300–400-page tome, reflecting the belief that more information equals better investor protection. In reality, such volume often obscures more than it illuminates—retail investors rarely read past the first few pages, and institutions prefer analyst notes to regulatory filings.

In the U.S., the S-1 registration statement is shorter, but compliance obligations under Regulation S-K and related rules are equally demanding. The key difference lies in presentation: India favors encyclopedic disclosure, while the U.S. emphasizes consolidated formats.

Thus, while both systems demand transparency, India is maximalist in form, the U.S. minimalist in format but no lighter in substance.

Market infrastructure: India’s technological leapfrog

If India is conservative in lawmaking, it has been bold in market infrastructure.

Dematerialization (Demat): India eliminated physical share certificates in favor of digital depositories, reducing fraud and speeding up settlements.

T+1 Settlement: India moved to one-day settlement, reducing counterparty risk and boosting liquidity.

Digital IPOs: Applications and payments are now fully online, seamlessly integrated with banks and exchanges.

The U.S., while stable, remains more conservative in adopting such reforms. India shows that emerging markets can lead developed ones in infrastructure innovation, even while maintaining rule-heavy legal frameworks.

Why it matters: Investor protection vs. market efficiency

These regulatory differences have real-world consequences.

India’s rule-based model offers clarity and reduces discretion but risks drowning participants in compliance checklists. The U.S. model, by relying on principles, fosters flexibility but can create uncertainty and uneven enforcement.

Similarly, India’s long prospectuses may satisfy regulators but undermine usability, while the U.S. system balances brevity with substance.

On infrastructure, India demonstrates that bold technological adoption—like T+1 settlement—can coexist with a conservative regulatory mindset.

Conclusion: Two roads, one goal

India and the U.S. may diverge in style, but their goals are the same: protecting investors, ensuring fair markets, and enabling capital formation.

India’s challenge is to streamline its regulations, moving toward leaner, principle-based frameworks without losing accountability. The U.S.’s challenge is to modernize its infrastructure and accelerate efficiency gains.

Far from being opposites, the two systems offer complementary lessons. India shows the power of technological boldness; the U.S. shows the value of principle-driven law. If each borrowed from the other—India embracing principles, the U.S. embracing technological speed—the result could be a regulatory architecture that is both flexible and future-ready.

We hope you are enjoying our “Investing in India” series and would love to hear your thoughts and suggestions. Feel free to drop us a comment anytime!

See you next time!

The US is innovation-heavy and has historically taken risks, largely because of its deep fiscal pockets and global dominance. It allows innovation to flourish first and only steps in with regulation once problems emerge—whether in the case of subprime mortgages or crypto. India, by contrast, cannot afford such risk-taking. With no deep fiscal reserves and a still vulnerable population, heavy regulation from the outset is necessary and rightly so.

But regulation without innovation only takes you so far. India’s infrastructure success is remarkable, yet it stems more from risk-averse policies than true innovation. Take AI as an example: Europe is focused on constant regulation, with little actual innovation, while the US gives innovators a free hand until something goes wrong because it can absorb the consequences.

The key point is that countries are at different stages of the cycle. India needs to strike a balance. A 300–400-page red herring prospectus is neither genuine transparency nor effective risk management; it is instead a compliance burden, an exercise in risk-avoidance that often includes everything even what is non-essential.

I don't have much understanding of US markets but I can say for sure that SEBI has done a phenomenal job in creating transpareincy. If there is one thing that works in India is SEBI, fast, precise and on the point. Yes, there are certain areas where regulator should let the market force decide. Over-all apart from last SEBI chiefs, everyone has done a great job in making the Capital Market move forward.