Google & Meta’s Big Problem

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Bad week for big tech

We have miles to go before the green transition

Bad week for big tech

Last week was arguably one of the most consequential weeks in the history of Big Tech.

For years, Big Tech looked untouchable. These companies dominated their industries — but more importantly, they had an iron grip on entire parts of our lives. They seemed too large and too complex to police — regulators spent years just trying to understand what they were up against. And now, if anything, they seemed poised to soar even higher, by fronting the development of artificial intelligence.

But last week was a reminder that they’re not infallible. In the space of a few days, two of the biggest tech companies on earth — Google and Meta — found themselves in landmark antitrust battles that could tear apart their empires. While these cases are all being heard in American courts, given the sheer scale of these businesses, the repercussions will touch the entire world — India included.

Here’s everything you need to know about what happened.

What even is antitrust law?

“Antitrust law” sounds like something complex and terrifyingly technical. It isn’t. It’s actually rather intuitive.

Here’s the key idea: in a free market, all businesses are kept in line by their competitors. If a business acts in a way that customers don’t like, others will quickly swoop in and take their business. For instance, imagine I sell cotton T-shirts for a living. One day, though, I suddenly try swapping the cotton out with some horrible, cheap, synthetic alternative to cut costs. All my disgruntled customers will abandon me and flock to my competitors, and I’ll suddenly bleed out revenue. And that’s why, in a well-functioning market, businesses have to do good by their customers.

This doesn’t always work, though. The free market falls apart if a business has too much ‘market power’ — if a business’ hold on its customers is too strong. Then, even if it short-changes its customers, there’s nowhere else for them to go. Imagine, for instance, that I have a complete monopoly in the T-shirt market — I’m the only person in town that sells T-shirts. No matter how horrible the material I use is, my customers have to buy from me. In a case like this, a business has an unhealthy amount of power over its customers.

This is why antitrust law tries to fight companies that try to kill competition through unfair means. While we won’t get into the complexities of the law here, you need to understand two ways in which you can violate these laws.

The first idea is “monopolisation” — or becoming a monopoly through foulplay. This doesn’t mean being a monopoly is bad in itself: if your product is way better than what your rivals have, or if you’re simply a much sharper businessperson, you could naturally end up as a monopoly. And that’s fine. But if you use shady means to get there: for instance, if you become a monopoly because you coerced shopkeepers so that they don’t stock your rival’s products, then that’s a problem.

The second, related idea is “restraint of trade” — where, instead of competing on merits, you try something underhand to kill competition. For instance, you could enter an informal arrangement with all the T-shirt sellers around you to only use cheap synthetic material, so that your decision to do so doesn’t hurt your topline. You’d be cheating your customers by playing outside the rules of capitalism, which is why antitrust laws would try and stop you.

These laws came up at a very different time. America’s Sherman Act, which is what Google and Meta are currently dealing with, is a law from 1890. The economy looked very different back then. Over a century of cases, regulators developed a playbook of how they enforced the law — all built around the physical economy.

And then, the digital economy wrecked that playbook. After all, this was a space where most businesses gave away services for free (or at least for data, instead of money), where individual companies invented entire industrial segments that they dominated freely, and where business arrangements could be infinitely more complex than was even theoretically possible with physical merchandise. For years, regulators were confused about how to port their old ideas to the digital economy. Most assumptions of antitrust law just didn’t work.

But, as the most recent wave of cases shows, regulators are catching up.

The Google ad-tech case

While it may not always seem that way, Google is, to a great extent, an advertising company.

It has a string of platforms for this. If you run a website where you want to host Google’s ads, you use the platform “DoubleClick for Publishers“ (DFP) — a sort of control centre for ad placement, that can pick and choose the ads that land up on your webpage. If you’re trying to advertise your business, you go to “Google ads” — which lets you create and place ads. If you’re a big company that’s running a more complex ad campaign with slots all over the web, you can use a more specialised service — “Display & Video 360”. Sitting in the middle of all this, Google has its own auction house, AdX, which connects advertisers with those displaying their ads.

Now here’s the thing: all of these, at least according to the US Department of Justice, are supposed to be entirely different functions. And because Google owns this entire pipeline, nobody else can pursue any of them as a business.

According to the DOJ, Google played unfair by linking all its ad platforms in sneaky ways. It had a massive reservoir of ad demand through services like AdWords — something that nobody else could match. All that business was routed through AdX, which made it far more powerful than any other ad exchange. And if a website wanted to use Google’s AdX auction house to get the best ad deals, Google forced them to use its DFP too, even if they preferred some other tool. Meanwhile, it also bought up DFP’s rivals, so that it could lock in all ad publishers to its service.

With so much of digital advertising under its thumb, it could try all sorts of underhanded tricks. For instance, in theory, any ad exchange could send ads to DFP, where they would all be evaluated through a neutral bidding process. In reality, though, ads from AdX got a massive advantage — DFP allowed it to look at the prices other exchanges offered, and outbid them by a single cent. This was just one of the many things that Google was doing.

In 2023, the DOJ complained to a district court that all of this violated the Sherman Act. And the court largely agreed. Last week, it passed an order holding that Google had a monopoly over both ad exchanges and serving ads to publishers — and it didn’t get there legitimately. It also found that Google had restrained trade by others in the process.

Google has a silver lining, though: the court didn’t see the business of sourcing ads — that is, its “advertiser ad network” — as a separate market. And if there was no separate market for sourcing ads, Google couldn’t have an ad sourcing “monopoly”. Whatever it did there was outside the scope of the court.

What comes next? The judge will now look at what can be done to fix things in the digital ads market. The DOJ wants to break up Google’s ad stack, and give part of the business to someone else — which would be a serious gut punch to the company. Google, meanwhile, is gearing up to appeal the order.

Make no mistake, this is a massive blow for Google. A few months ago, it had been hit by a similar decision that challenged its dominance over the search engine market. The two, together, make up over 80% of its $300 billion+ revenue. All of this is now under threat. While things are up in the air right now, there may be a day in the near future when Google, as we know it, doesn’t exist — the internet giant is pulled apart into many different companies.

But that’s just one of the big stories from last week.

The Meta trial begins

A massive new antitrust trial began against Meta last week.

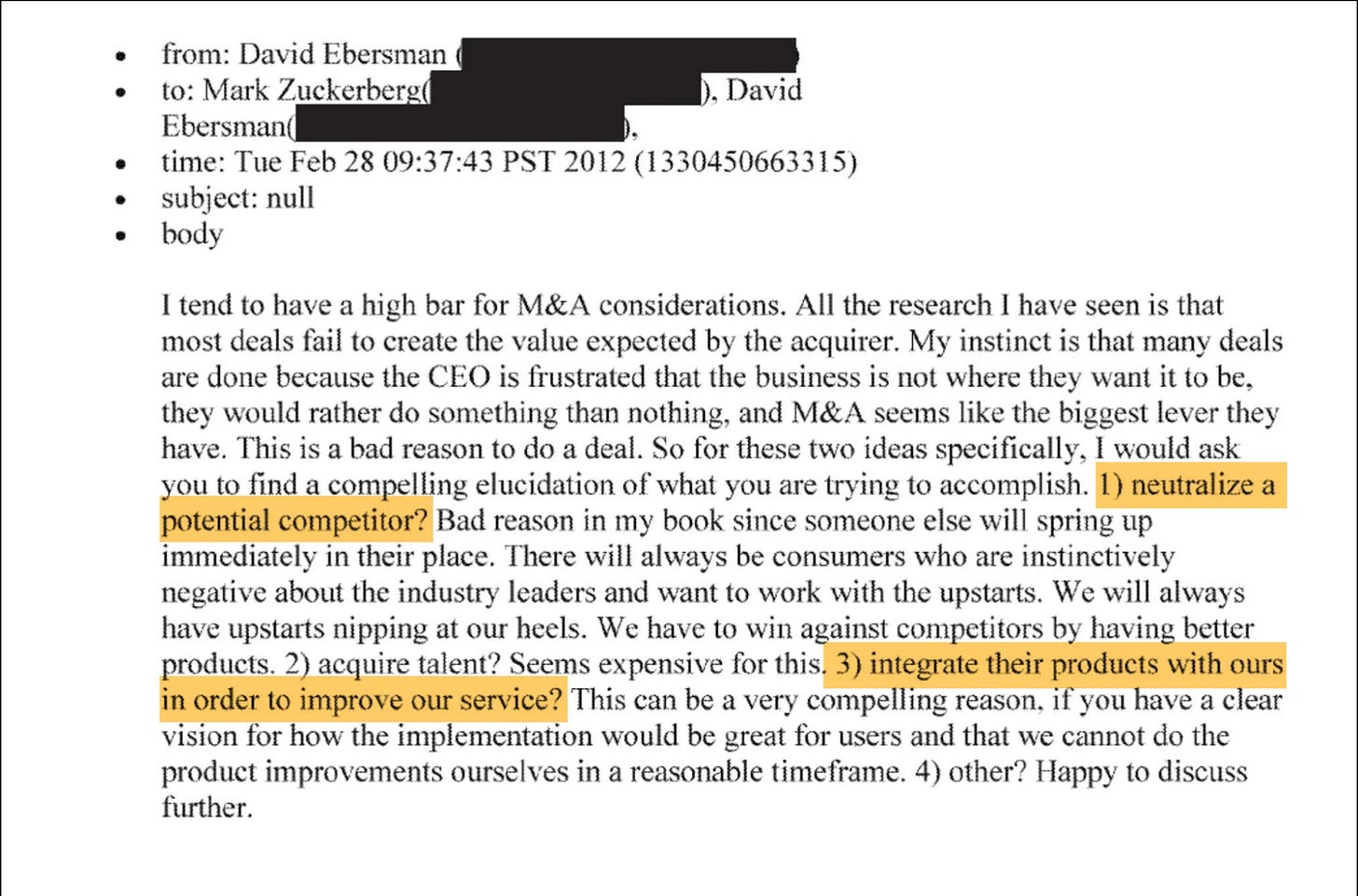

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) claims that Meta has a monopoly over social media — one that wasn’t earned by merit, but by running a “buy or bury” ploy against any platform that looked like it might be a danger to the company. The FTC channeled a massive repository of old emails to show that the company actively monitored its competition — and tried buying out anything it considered a big deal.

Take Instagram, for instance, There are mails from 2011 and 2012 that clearly show Zuckerberg worried about Instagram — a service that, even back then, felt extremely addictive, in exactly the way that Facebook was.

The fact that Instagram could, one day, become a Facebook-killer prompted the it to take the company over — at least in part.

Whatsapp had a similar story. The platform seemed to be beating Facebook’s own offering — Messenger. To get around the competition, Facebook acquired it.

Meanwhile, Meta also allegedly had some dirtier tricks up its sleeve. For instance, it has supposedly used a variety of services to spy on user’s phones and track any other apps that could, some day, be a competitor.

To the FTC, this is a clear example of monopolisation. Meta’s modus operandi, it believes, is to secure its dominance in social media by spying on and snapping up its competitors. That in itself, though, isn’t enough to make a convincing antitrust case. The big question before the court, now, is whether Meta has a monopoly over its market.

That’s a trickier question than it appears. Think about it: what’s the “market” for social media? Do social media companies only compete with other social media companies? Or do they compete with anything else that demands your attention, from Netflix to Youtube? If our theory is that having a monopoly allows businesses to mistreat their customers, does Meta qualify? Does its userbase have nowhere else to go — do they actually crave the specific features Facebook or Instagram provides, and will stick around for those no matter how terrible they become? Or will its userbase switch to something other than social media altogether, because all digital platforms ultimately just serve up entertainment?

There’s no clear answer to the question. That’s why this whole thing is so fascinating. While the FTC thinks that Meta has a monopoly over “personal social media”, Meta argues that even if it holds a huge part of the social media market, it doesn’t have the power to do whatever it wants. That power is checked by platforms like YouTube or TikTok.

Meanwhile, Meta certainly isn’t comfortable with this case looming around its neck. If the FTC succeeds, it might just force Meta to hive off business verticals like Instagram and Whatsapp. All the company will be left with, then, is Facebook — an aging platform that is losing young users. According to the Wall Street Journal, it was willing to shell out as much as $1 billion to make the case go away. The FTC, on the other hand, considered the case as being worth far more. It refused to settle the case for anything less than $18 billion. That’s why the company’s now in court.

New waters for Big Tech

Big tech companies are no strangers to antitrust disputes. But this is arguably the strongest push they’ve seen. In a worst case scenario, Google and Meta might see the hearts of their businesses torn out. But they aren’t the only big tech companies that antitrust authorities are going after. The Department of Justice, for instance, has sued Apple — claiming that it maintains a monopoly in the smartphone market, which it uses to shut others out. Amazon, meanwhile, is dealing with its own antitrust woes, having been sued by the FTC for allegedly punishing sellers that try selling anywhere outside Amazon.

Some of these were the legacy of the Biden years. Big tech companies had come to see Donald Trump as a wildcard that they could get under their control. After all, he’s been public with his intention of striking deals of all sorts, and Big Tech was listening. Meta, for instance, contributed a million dollars to Trump’s inaugural fund, while Zuckerberg had several meetings with the US President at Mar-a-lago.

This also probably explains this photo from Trump’s inauguration.

But Trump has been more unpredictable than they thought. Even though Trump made massive changes in both the DOJ and the FTC, these departments have maintained continuity with their Biden-era policies. Despite all the attempts by Big Tech to appease the President, clearly, it doesn’t look like he’s in the mood to give them any respite.

And going by last week, that’s seriously bad news for Big Tech.

We have miles to go before the green transition

If we have to get serious about the green transition, the first thing we need to do is to stop kidding ourselves. The naked truth is that a complete energy transition is still many decades ahead of us. In the meanwhile, we’ll simply have to trudge through any surprises climate change throws our way.

See, if you’re hoping for a quick transition to renewable energy, you should look for exponential growth. Every year, new renewable sources should take up more and more of our energy mix, until — within a generation or so — they are the dominant source of all the energy we need. In some datasets, you actually see exponential growth of that sort, at least when you look at solar energy. In absolute terms, our capacity to generate renewable electricity is going up at breakneck speed.

Charts like this, to many people, are a sign of hope: that solar energy will pull us out of climate change at the eleventh hour. But there are reasons to be sceptical, as we’ll discuss below.

A recent JP Morgan report carries a sobering reality check. The bottom line is this: despite trillions in investment, we aren’t seeing the exponential increase in the pace of our green transition one hopes for. Instead, the share of renewables in our energy mix is growing at a slow, and worse still, linear rate of 0.3%-0.6% a year. If things stay this way, you should expect a slow transition to green energy over the course of many decades, even as we continue to pump carbon into the atmosphere. Unless we hit some sort of dramatic inflection point where the economics suddenly make renewable energy a no-brainer, things probably stay this way.

At the cost of leaving you depressed about the state of the world, today, we’re going to break down what they say.

Why you shouldn’t trust the hype

Let’s look at all those beautiful hockey-stick curves again. They look hopeful, don’t they? But there are a few key reasons you shouldn’t trust them:

Intermittency

You’ve probably already heard of how renewables like solar and wind energy have a bad intermittency problem. The sun doesn’t always shine, the wind doesn’t always blow — and when they don’t, power plants that rely on them stop functioning.

But this is also something you have to remember whenever you see any statistics on solar energy. Consider capacity addition, for instance: there’s a lot of data on how our installed capacity for solar power is going up substantially. The problem, though, is that all that capacity very rarely translates into actual electricity. Solar plants, the world over, have capacity factors of 15-20%. That is, solar power plants usually generate 15-20% of the electricity that they could in theory.

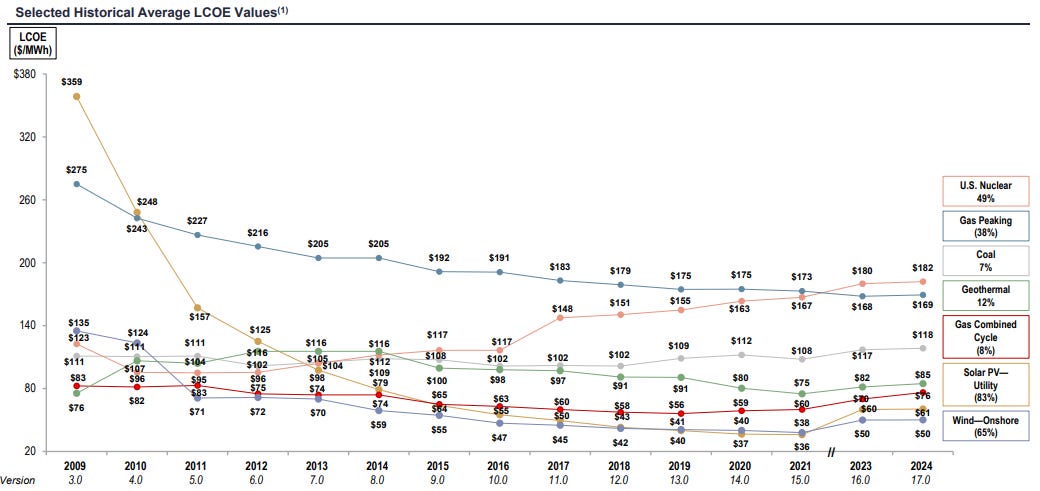

That’s essential context whenever you look at graphs like this:

Whenever you see statistics on ‘solar capacity addition’, you should expect the actual electricity it creates to be less than one-fifth that amount. And so, as per JP Morgan’s estimates, solar power still makes up just 7% of the electricity the world produces.

Non-electrical uses

There’s another catch: while renewable sources are taking up a large share of electricity generation, at least in advanced economies, that’s just a fraction of all the energy we need. In most countries, electricity makes up one-third of all their energy needs. There are still major uses of energy — like transportation, industry or heating — that electricity is simply no substitute for. Factor those in, and the role of renewables in countries’ energy mixes shrinks.

This is, as far as we can see, a necessary hurdle to cross. Human prosperity, beyond a doubt, depends on various energy-intensive industrial processes — like the production of steel, chemicals, fertilisers, plastics, etc. And sadly, the more energy-intensive an industry is, the better suited it is to using fossil fuels. These processes need a reliable source of high-temperature heat, and for that, fossil fuels are your best bet. This part of the economy, therefore, is going to be the hardest to decarbonise. 80-85% of the energy demand from these industries has to be fulfilled through fossil fuels.

All of this means that even if we decarbonise our entire grid — a tall order in itself — weaning ourselves entirely off fossil fuels is a much more complex project. In the interim, renewables will be considerably less important in our energy mix than one hopes. Going back to solar energy, for instance — while it has a 7% share in the world’s electricity production, it only makes for ~2% of the world’s total energy needs.

Transitions always take time

None of this is meant to diminish the importance of the green transition. It’s only meant to impress on you the fact that we aren’t on some sort of glide path away from fossil fuels. Those will, sadly, be around for a lot longer. This is simply meant to temper your expectations on how things will play out going ahead.

As the scholar Vaclav Smil points out, energy transitions always take a long time. Energy, after all, isn’t a luxury: it’s something that absolutely every living person uses, and they have their own ways of doing so.

Consider coal: coal emerged into a world where people were burning wood and straw, back in the 1800s. By 1840, well into the Industrial Revolution — it still catered to just 5% of the world’s energy needs. It would take another 60 years for it to supply half the world’s energy demand. And despite that, today, in large parts of the world — including in India — people still use wood and other biomass for their energy needs.

Crude oil, similarly, burst into the scene towards the beginning of the 1900s. It only surpassed coal use in 1964, half a century later. Natural gas, which entered the scene a few decades after crude oil, hasn’t caught on in most of the world.

None of this dictates the speed with which we’ll make the green transition. But they can give you a sense of the direction it might take. An energy transition isn’t just a matter of changing an energy source: you need to master new production techniques, distribution channels and machinery, which requires a worldwide build-up of infrastructure. In the past, we’ve accomplished this sort of thing over the scale of generations.

If we believe this time is any different, we should at least know why.

You need an economic case for a faster transition

There have been a few cases in history where we’ve made rapid, industry-wide transitions within the space of a couple of decades. As the report notes, we shifted steel production from open hearth furnaces to considerably more efficient technologies, like electric arc furnaces, within a space of just two decades. This cut down the energy we spent on creating steel to almost one-tenth of what we once needed.

So how did we pull it off? Well, there was a strong economic case for such a shift. That is, the shift should, in some way, finance itself.

So far, there isn’t a strong economic case for renewable energy. To be fair, there’s evidence that, in specific conditions, renewables are actually cheaper than fossil fuels. But it appears that both the solar and wind industries are maturing, and our ability to improve both technologies is hitting physical limits. If this is true, there’s little hope that prices will go down even further.

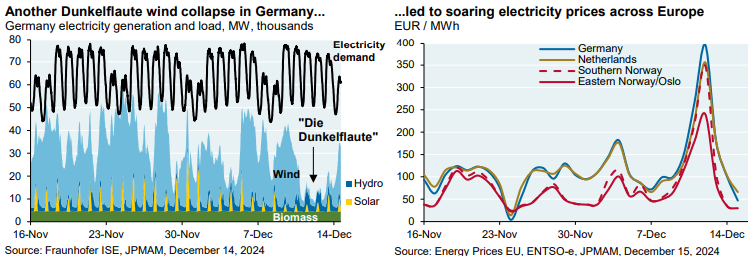

For early movers, decarbonisation presents a mixed picture. Consider Europe, where renewables meet half of all electricity requirements. Energy prices have sky-rocketed across the continent: they’re now 5-7x as expensive as they are in India. Part of this is simply because Europe lost access to piped Russian gas. But this is also, in part, a result of how vulnerable the continent has become. This has a variety of serious and far-reaching implications — such as the fall of Germany’s industrial competitiveness.

The true cost of renewables doesn’t just lie in high prices, though: it lies in the uncertainty. For instance, MISO, which operates the grid in much of the American Mid-west, has been raising the alarm on its shrinking ‘reserve margin’. It believes that at least during peak summer, increasingly, it’ll find it hard to match electricity demand with supply — creating a risk of large-scale blackouts.

The worst case scenario played out in Germany, earlier this year. Germany has periods of ‘dunkelflaute’ when it becomes dark, and the wind stops blowing. The intermittency suddenly became a crisis. Electricity generation cratered for a few days: and because Europe’s grid is connected, it sent prices soaring everywhere from Netherlands to Norway. This surge in prices led, indirectly, to the collapse of Norway’s government.

For the green transition to come to fruition, these are problems that we will have to solve.

What should you take away from this

(… other than despair, that is?)

When it comes to climate change, we can’t afford to be complacent. We shouldn’t confuse momentum for hitting escape velocity. While we’ve made massive strides in harnessing solar and wind energy, we’re nowhere close to replacing fossil fuels altogether. In real terms, the shift to decarbonisation is excruciatingly slow.

This doesn’t mean the green transition is doomed, and it certainly doesn’t mean that it’s unimportant. It just means the green transition won’t be quick. It won’t arrive like a consumer tech upgrade, where people across the world rush towards the newest technology. Expect a slow, uneven process that plays out over the course of a few decades, with plenty of hiccups in between. And worse still, expect it to be linear.

Is there a quicker way? There may be, but it won’t be easy. It’ll require a deep, structural change to the economics of the green transition. It’ll require conditions where the green transition finances itself. If there’s one thing to take away from this piece, however, it is that we’re nowhere close to hitting that inflection point.

Tidbits:

State-run telecom operator Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd (MTNL) has defaulted on loans worth ₹8,346.24 crore borrowed from seven public sector banks, according to a regulatory filing dated April 19, 2025. The largest portion of the defaulted amount is owed to Union Bank of India at ₹3,633.42 crore, followed by Indian Overseas Bank at ₹2,374.49 crore and Bank of India at ₹1,077.34 crore. Other affected lenders include Punjab National Bank (₹464.26 crore), State Bank of India (₹350.05 crore), UCO Bank (₹266.30 crore), and Punjab & Sind Bank (₹180.30 crore).

Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd. (BHEL) posted a 19% rise in revenue for FY25, reaching ₹27,350 crore, supported by strong order inflows worth ₹92,534 crore during the year. Of this, ₹81,349 crore came from the power sector, while ₹11,185 crore was contributed by industrial segments including transportation, defence, and process industries. The company’s total order book at the end of FY25 stood at ₹1.95 lakh cr.

India’s average crude oil import price fell to a 47-month low of $68.34 per barrel in April 2025, down 5.6% from $72.47 in March, according to the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell. This marks the lowest level since May 2021. Despite the price dip, India’s import composition in FY24 was dominated by sour crude at 78.5%, with sweet crude accounting for just 21.5%. Crude oil imports rose 4.2% to 242.4 million tonnes, while the import bill climbed 2.7% to $137 billion. Including petroleum products, the total import bill stood at $161 billion.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉