The Fall of Germany’s Car Giants?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why German car-makers are in trouble

Ferguson’s Law: Why the United States should be very worried

Why German car-makers are in trouble

Here’s an interesting headline we came across recently: Audi to cut 7,500 jobs in Germany to become more efficient. Now, on the face of it, this might look like a normal restructuring that a company might do to improve their numbers. But it marks a broader trend: Germany’s famous automotive industry — famed for making cars that you dream of owning someday — is in deep trouble.

Let us start by giving you some context.

You see, the world’s big three auto manufacturers — Volkswagen (which owns Audi), BMW, and Mercedes — all hail from Germany. This industry is extremely important for Germany’s economy. It accounts for a huge portion of Germany’s GDP — roughly 5% — and more than one-tenth of its exports.

The industry is also a big employer. Not only do automotive manufacturers employ hundreds of thousands of people on their own rolls, but they also sustain a massive supply chain, indirectly creating millions of more jobs. In all, 5.3 million German jobs are dependent on the automotive sector. For context, that is one in every seven of the country’s jobs.

At its peak, Germany was producing over 6 million cars annually, with exports flooding into markets worldwide, from the U.S. to China. Chances are, every really rich person you know owns one of those cars. For years, everything was going right. Profits were pouring in, the brands were expanding, and demand was strong.

But then, things changed.

In 2018, sales started to plateau. By 2020, as the world was hit by the pandemic, they collapsed.

When the world reopened, German automakers found themselves in a vastly different reality. Their dominance was slipping. These job cuts, perhaps, are a result of this

Why did the German auto industry decline?

Now, we can’t point to a single specific reason why the German auto industry is in deep trouble. The landscape is complex, and we aren’t fans of ascribing single causes to complex events. Even so, we read through a bunch of things, and this is our best understanding of everything that might be relevant.

1. The China problem: When customers become competitors

Yeahhh, we’re back to China once again. As we’ve told you a million times before, China impacts everything. China is perhaps the single largest factor behind the decline of German auto manufacturing.

See, China was once a goldmine for German automakers.

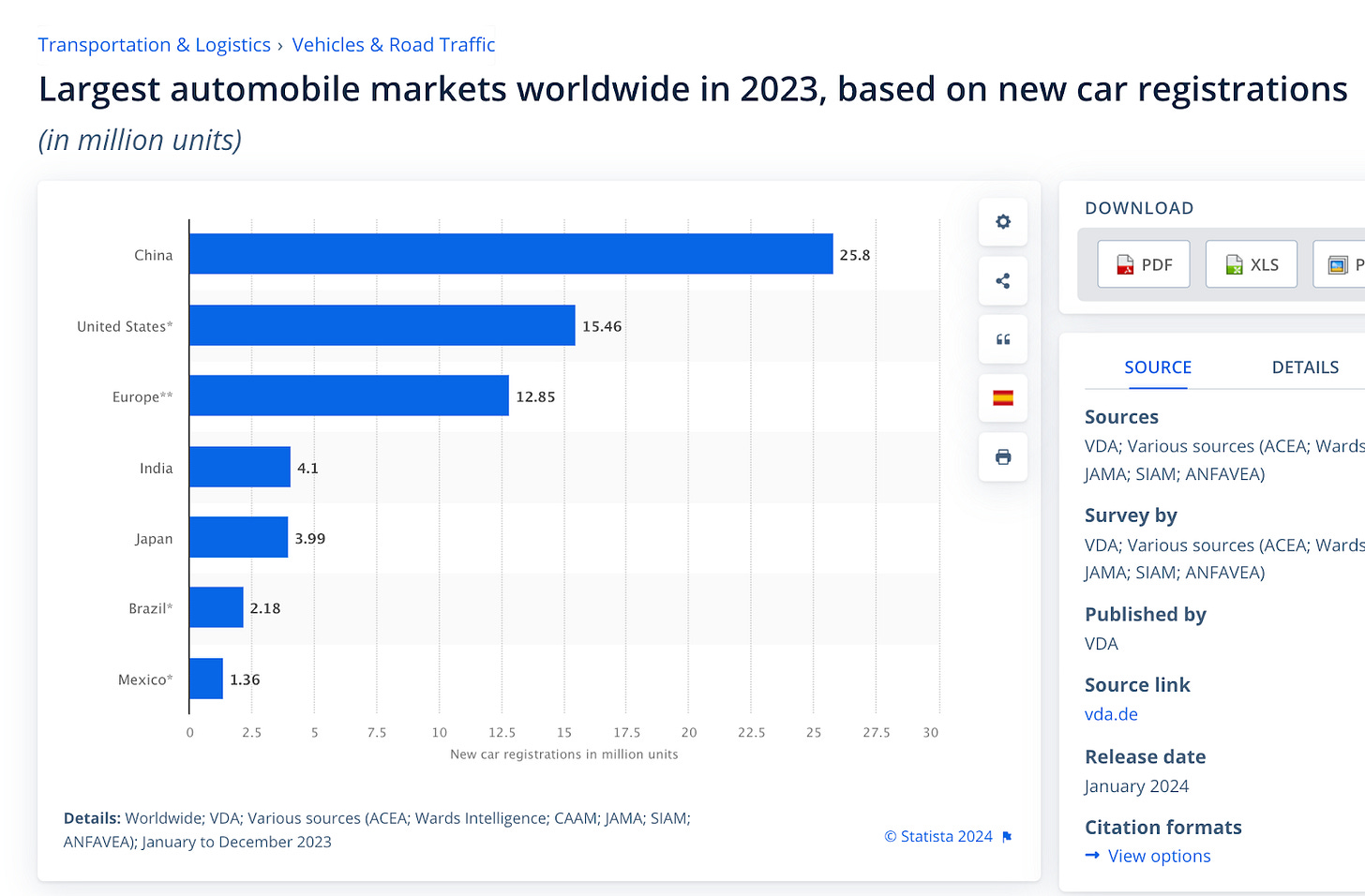

For example, in the late 2010s, Volkswagen was selling 40% of its global cars in China. BMW and Mercedes also derived a decent chunk of their revenue from the Chinese market. That’s a really huge dependence on just a single country. If anything at all hurt the demand they received from that one market, it would hurt those giant automakers terribly.

Well, that’s exactly what happened.

By the end of the pandemic, that dependence on China was quickly turning into a liability. German brands started bleeding market share in China at an alarming rate. By 2024, their combined market share in China had fallen to just 15%, down from 25% five years ago.

Why was that?

See, over this time, China’s home-grown car companies were exploding in popularity. The country was suddenly turning into a global automotive powerhouse.

Chinese consumers overwhelmingly chose domestic brands, particularly for EVs, over German cars. Companies like BYD created competitive electric vehicles that rivaled and even surpassed German offerings in price, range, and technology. Meanwhile, the German automotive majors were late to embrace EVs. Their early models were either over-priced, underwhelming in range, or plagued with software issues.

This wasn’t just about failing to produce good EVs. Germany also didn’t invest in the battery supply chain early enough. Most German EVs rely on imported batteries, primarily from China and South Korea. This made them vulnerable to supply chain disruptions and cost fluctuations. Meanwhile, their Chinese rivals made those batteries in-house.

Volkswagen and BMW have now scrambled to build battery plants in Europe, but they are years behind Tesla and Chinese battery giants like BYD and CATL.

Meanwhile, Chinese EV imports into Germany were also surging. China’s own domestic market wasn’t big enough to absorb all the cars it was making. They needed new customers to sell to. As a result, Chinese automotive manufacturers began to look abroad. Europe was one of the key markets they targeted.

In the first half of 2023, Chinese EV imports into Germany rose by 75%. Companies like BYD offered high-quality EVs at lower prices than their German counterparts. European consumers rushed to embrace them.

Things escalated even further when Germany ended its EV subsidies in late 2023. This broke German auto-manufacturers last line of defence, causing a sharp drop in German EV sales. Chinese brands, already priced lower, gained even more momentum. The subsidy cuts, meant to reduce government spending, instead tilted the playing field against domestic automakers. Sales declined even further.

Germany has excellent trade relations with China — after all, China is the biggest market for most of Germany’s exports. And that’s only possible because Germany had cozy ties with the Chinese government. But when businesses from the two countries clashed, this became a political problem.

When the EU launched an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs to curb imports, for instance, Germany actively lobbied against it. Similarly, when the EU mooted tariffs on Chinese EVs, Germany voted against it. After all, Volkswagen and BMW feared retaliation that could hurt their China business further. The German government found itself in a difficult position: defend its own industry or avoid angering China.

In the end, though, the EU moved forward with 45% tariffs on German EVs — over the objections of the EU’s largest car-makers.

But beyond this, there were two other, albeit smaller, reasons as well.

2. The energy crisis and the Ukraine war

The war in Ukraine had immediate and far-reaching effects on German industry — including its auto industry. Before the war, Germany depended heavily on Russian natural gas to power its factories. In fact, before the war, nearly 55% of Germany’s natural gas supply came from Russia. When the conflict began, and sanctions were imposed on Russia, that supply was severely disrupted. Energy prices went soaring.

Making a car, as you can imagine, is an energy-intensive process. The increase in energy prices was a sudden shock. It squeezed profit margins for automakers who were already struggling with supply chain disruptions from the pandemic. For context, today, German automakers pay 3-5x as much as their competitors in the United States or China for energy — even after the initial shock subsided. Suddenly, running the factories became much more expensive. And so, the industry was severely hit with a double blow: declining demand and rising costs.

3. Overcapacity and high labour costs

During its boom years, Germany built enormous production capacity. But now, with demand declining, many of these factories are underutilized. And naturally, running plants that aren’t producing at full capacity is expensive.

Unfortunately, German auto manufacturers don’t have much breathing room to cut costs, when faced with a crisis.

Consider Germany’s high labour cost. German autoworkers are some of the best-paid in the world. They run on a co-determination system, which ensures that unions have a major say in corporate decisions. Half of the supervisory board seats in large German companies are held by worker representatives. That means any layoffs or cost-cutting measures can’t go through easily — they have to be negotiated extensively.

This system has major benefits for workers. It provides job security and prevents abrupt mass layoffs. But in a crisis, it also makes restructuring much slower and costlier. For example, Volkswagen was on the brink of shutting down one of its 87-year-old German factory (which, by the way, goes to show how big of a mess they are in), but unions intervened and forced a compromise that delayed the decision. That forced the company to maintain an unprofitable plant when it was no longer useful.

The Fallout: Job Cuts, Pay Cuts, and Lobbying in Desperation

The impact of all these challenges has been devastating for the German auto industry. And with Trump threatening tariffs on European cars, more uncertainty looms. The auto majors have now been forced into survival mode.

Companies are pushing for all kinds of cost-cutting measures, including pay cuts and restructuring deals with unions. Audi entered a deal with its unions and announced it will cut 7,500 jobs by 2029 – 8% of its workforce. Perhaps to keep its unions happy, it has promised that the cuts won’t come at the shop floor, but from its administrative and development departments. Volkswagen, similarly, has plans to reduce its workforce by 35,000 by 2030.

Meanwhile, automakers have also turned to lobbying the government for support. They’re pushing for everything from new EV subsidies to looser climate regulations. But the German government faces a dilemma — it wants to support its auto industry, but it also needs to balance European climate policies and trade relations with China.

None of this guarantees success. It’s quite clear that Germany’s auto industry is in an existential crisis. They were once a global powerhouse, but now, they’re struggling to compete in the very market they once dominated.

Will they survive? Or will they become the next Nokia? We’re watching keenly.

Ferguson’s Law: Why the United States should be very worried

If you’ve been around finance types — and let’s face it, if you’re reading this, you probably have — you likely have an opinion on America’s debt burden.

After all, it’s hard to argue with graphs like this:

As the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. enjoys a privilege few other countries do: the world is always willing to lend it money. For decades, America has been running on borrowed money. But recently, the sheer scale of its borrowing has gone off the rails.

Consider this: between the Cuban Missile Crisis and the fall of the Berlin Wall — that is, at the very height of the Cold War — U.S. interest payments averaged just 1.8% of its GDP. Today, that number has surged past 3%, and it’s still climbing. Meanwhile, deficits as a share of its GDP continue to grow.

Intuitively, this feels unsustainable, right? After all, how long can a country — even if it’s the world’s most powerful economy — live off debt? Sooner or later, an ever-expanding interest burden has to hurt, right? Anyone in Pakistan or Sri Lanka could tell you that when a country becomes preoccupied with paying off its debts, things fall apart. And yet, when you look at the sheer might of a country like the United States, it’s hard to imagine its borrowing spree leading to real consequences.

So, is there a point where even a superpower like the United States should actually be worried? Historian Niall Ferguson tackles this question in a recent paper. Looking at empires across history, he suggests something he calls “Ferguson’s Law”: when a Great Power spends more on debt servicing than on defense, its power begins to fade.

Now, Ferguson is a controversial thinker. Previously, for instance, he argued that the British Empire was, on balance, good for India. But regardless of where you stand on his broader views, we thought this idea was worth exploring. So let’s do just that.

Ferguson’s law

Here’s what Ferguson suggests: when a “Great Power” — such as the modern United States — spends more on debt servicing than on military spending over a long time, it hits a tipping point. Beyond this point, it loses power and becomes vulnerable. Now, one-off moments of fiscal strain don’t trigger this. If there’s a sustained breach of this limit, however, all bets are off.

This is what he calls “Ferguson’s Law” (not after himself, incidentally, but after the 18th-century philosopher, Adam Ferguson).

There are two parts to this “law”: borrowing, and military spending.

Fiscal deficits look great in the short term. They have a “tax-smoothing” effect: if a government needs to spend lots of money for some reason (such as a major war), it doesn’t have to immediately ask its population to shell out huge amounts in tax — which would ruin its economy and create chaos. Instead, it can borrow money, and distribute the tax burden over a long period of time.

This makes complete sense in a crisis. The issue arises when countries run deficits as a regular habit, letting their debts accumulate over the years. Year after year, countries find themselves paying off an ever-growing debt burden.

You can still pay this debt off if you’re growing at a robust pace. But you can’t promise perpetual growth. When growth stops, those debts accumulate, and countries can quickly find themselves in a debt crisis. If that happens, all bets are off. Countries have to take tough decisions that leave people unhappy — such as slashing budgets, defaulting on debt, or inflating their currency. All of these can have disastrous political consequences.

But why does Ferguson link debts to military spending? Well, because the “power” of a Great Power comes from its military might. When countries suppress their military budgets, in the short term, things seem just fine. In the long term, however, it drains their military readiness. Countries can end up with obsolete equipment, inadequate troop training, and unfulfilled modernization programs. These gaps only come to light during major wars, when their abilities are already being tested.

It is the military of a Great Power that lets it “project” its strength across the world. As that ability declines, rivals believe that it may no longer be willing or able to assert itself on the world stage. They then try to challenge that power’s geopolitical standing. This can hasten its decline.

Now, here’s something worrying: for the first time in nearly a hundred years, in 2024, the United States breached Ferguson’s Law. Its debt servicing costs have hit 3.1% of its GDP, while its military spending is at 3% of its GDP. Is this a sign of bad times ahead?

Some historical examples

To support his argument, Ferguson looks back at history, to the Great Powers of the last five hundred years that no longer have that status today. We can’t really do justice to them here: we’d strongly recommend that you go to his paper. But here’s a brief gist.

Habsburg Spain

In the 16th century, Spain was the world’s greatest superpower. It commanded literal mountains of silver in the new world. Its elite infantry — tercios — and its vast naval fleets allowed it to project power across continents. However, its military ambitions outpaced its financial capabilities.

With silver flowing in from the Americas, Spain got away with deep fiscal mismanagement for years. But by the late 16th century, the strain was showing. Between 1575 and 1583, it breached the Ferguson Limit for the first time. Debt servicing consumed an unsustainable portion of its revenues. It defaulted on its debts multiple times, weakening its ability to fund its military. After many long wars, it ultimately lost the Eighty Years’ War to the Dutch — who were more prudent with their money. By the mid-17th century, Spain’s dominance had faded, and the rest of Europe had left it behind.

Ancien Régime France

France, under Louis XIV, was perhaps the most powerful state in Europe, with a massive army and a formidable economy. However, it had unending, serious troubles with fiscal management. The breaking point came when it decided to intervene in the American Revolution. Suddenly, it sharply exceeded the Ferguson Limit. By the late 18th century, servicing debt took up more than 50% of the French budget, crowding out its ability to spend on military or administration. The resulting fiscal crisis triggered political upheaval, ultimately leading to the French Revolution.

In contrast, its main rival, Britain, had developed stable financial institutions to manage its debt. This allowed it to outlast France in its global struggle for power, helping it secure its dominance in the 19th century.

The Ottoman Empire

The Ottomans once controlled vast swathes of the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. But by the 19th century, their sources of revenue dried up, even as the costs of running a modern state kept ramping up. They became financially dependent on foreign creditors.

Over the 1800s, the empire fought a series of wars, which were all bankrolled through borrowing. That pushed it to breach the Ferguson Limit. By the 1870s, over half of the Ottoman budget went to servicing debt. The empire soon defaulted on these debts. Its European creditors set up the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA) — and took charge of its revenue streams. Its military entered a period of chronic under-spending, weakening the empire just as European powers were modernizing their forces. It suffered a series of military failures in the Balkan Wars and eventually collapsed.

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary once controlled a sprawling empire in the heart of Europe. But its finances were precarious. It had a complicated system of revenue collection, however, which pushed it into constant deficits. Because of this system, it constantly prioritized debt servicing over military spending.

By the early 20th century, it breached the Ferguson Limit several times, leaving its army chronically underfunded. This lack of preparedness was evident in World War I, when Austria-Hungary struggled to keep up with the modernized militaries of Germany and Russia. The war proved catastrophic, and by 1918, the empire disintegrated.

The British Empire

The British Empire, to some extent, looks like an exception to Ferguson’s Law. It is the historical example that is closest to the United States. Britain built strong institutions that could handle its debt — like the Bank of England, a stable bond market, and a reliable taxation system. These allowed it to service the debt without sacrificing military power. Even as interest payments consumed a significant portion of its budget, Britain continued to fund a world-class navy and sustain its empire.

But even Britain couldn’t fight Ferguson’s Law forever. Between the two world wars, it was in constant breach of the Ferguson Limit. Even though it survived as a Great Power for some time, it did so through a policy of financial repression. Over time, this ate into the power of its currency. When the U.S. and Soviet Union emerged as superpowers, Britain could no longer afford to maintain its global dominance.

What should you take away from this?

It would be a mistake to take Ferguson’s Law to be some iron-clad law of nature. It is probably more of an interesting statistical correlation. It’s hard to conclude anything by looking at a handful of examples, and this is no exception. There’s no guarantee that the United States is doomed because of its fiscal profligacy.

But that’s not the point. This paper does not predict the future. But it should give you a way of thinking about America’s debt burden. It gives you a sense of what is possible. The United States, today, is more indebted than it was immediately after the Second World War. The consequences of this need not be immediate, but that doesn’t mean there will be none. Debt, as Morgan Housel says, narrows the range of outcomes one can endure. The United States’ high debt burden may push it to make compromises on what it can spend on. In periods of crisis, those compromises may well hurt it more than it realises.

For how that might happen, we recommend you take a look at the paper — for how the strongest countries on Earth over the last five hundred years have all, turn by turn, lost that status.

Tidbits

Tata Motors and Kia India will increase passenger vehicle (PV) prices from April 2025, marking their second price hike this year to offset rising input and commodity costs. Tata Motors has not disclosed the exact percentage increase but confirmed that the hike will apply to both electric and conventional PVs, following a 3% rise in January 2025. Kia India will raise prices by up to 3% across its lineup, effective April 1, 2025, citing supply chain and commodity cost pressures. This move follows Maruti Suzuki's 4% price hike announcement for April. Tata Motors sold 4,18,991 units in the first nine months of FY25 (April-December), while Kia recorded 2,29,682 units in 11 months, aiming to reach 3,00,000 units by the fiscal year-end. The price adjustments come amid a 10.34% YoY drop in PV sales in February 2025, with 3,03,398 units sold, as per the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations (FADA).

India, the world’s second-largest steel producer, is considering a 12% safeguard duty on most steel imports for 200 days to counter rising inflows, particularly from China, which saw an 80% surge in steel exports to India, reaching 1.6 million tons in the first seven months of 2024. The move follows requests from Indian steelmakers, including Jindal Steel and Power Ltd. and JSW Steel Ltd., seeking protection against cheaper imports. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry stated that delaying the duty could cause irreparable damage to the domestic sector. The final decision will be made after a hearing, but if implemented, it could impact steel prices and trade flows. Several nations, including Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Chile, have also imposed trade measures amid global steel oversupply.

Alphabet Inc. has announced its biggest acquisition to date, acquiring cloud cybersecurity firm Wiz Inc. for $32 billion in cash. This comes less than a year after Wiz rejected Google’s $23 billion bid, citing the potential for a higher valuation through an IPO. Founded in 2020, Wiz had reached a $12 billion valuation in a funding round in May 2024 with investors including Sequoia Capital and Greenoaks. The acquisition will strengthen Google Cloud’s security offerings as it competes with Microsoft and Amazon, though regulatory hurdles remain a key risk. The deal, subject to regulatory approvals, is expected to close in 2026.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Thanks for the Article . Well written to the point 👏