From AAA to ashes: The DHFL story

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

DHFL and the mystery of the missing Bandra branch

India’s real estate sector: Three roads to one destination

DHFL and the mystery of the missing Bandra branch

Dewan Housing Finance Corporation Limited (DHFL) was, until just a few years ago, one of India’s largest housing finance companies. Over nearly forty years, it had created an empire around providing affordable home loans to lower- and middle-income Indians. By the mid-2010s, it claimed to have a sprawling, India-wide retail network, and a loan book that had crossed ₹1 lakh crore. It was, in short, one of India’s biggest financial giants.

On paper, its business was identical to any housing NBFC. At one end, it would raise money from banks, mutual funds, and bond investors. At the other, it would lend that out as secured housing loans. The spread was where it earned for itself. With a portfolio of lakhs of small, secured home loans, it seemed like one of the most stable variants of this business — a business that was inherently well-diversified — bringing it high credit ratings and the trust of many investors and lenders.

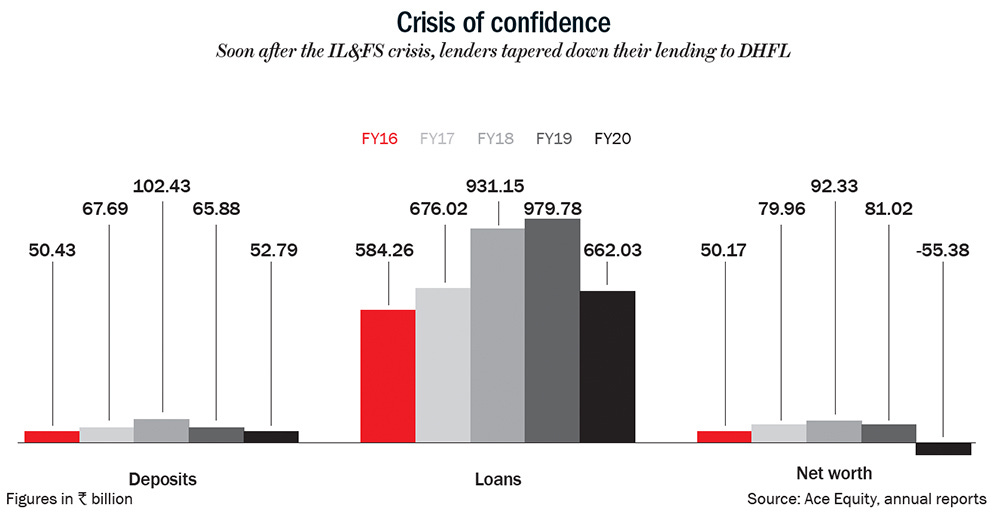

Then, in late 2018, India’s financial system nearly collapsed, when the financial giant, IL&FS, fell apart. The entire industry went into a panic as shockwaves rippled through. Banks and mutual funds started taking a cold, hard look at their exposure to NBFCs.

Under the harsh light of that scrutiny, DHFL’s empire suddenly looked fragile.

By early 2019, investigative journalists were pointing to the possibility of a giant fraud worth tens of thousands of crores at the heart of DHFL. Investors’ moods had soured. The company’s stock price fell sharply, while its borrowing costs spiked.

Soon, DHFL was struggling to keep its head above water. In the space of a year, it had gone from being India’s third largest housing finance company, to one whose very survival was in question. It stopped disbursing fresh loans, and began fire-fighting with its lenders. Those lenders asked for forensic and transaction audits. The deeper they dug, the more suspicious it all seemed. The company, it appeared, was built on a foundation of lies.

At the heart of it all, it seemed, were the company’s flashy promoters — the Wadhawan brothers.

By late 2019, the RBI took over the company, kicking out its board and appointing an administrator in its stead. The company was forced into an insolvency process, while the administrator began working to uncover what had actually happened. The information uncovered here has now become the basis of a new SEBI order against the company’s erstwhile promoters and officials.

A lot of this wrong-doing centred around the company’s mysterious “Bandra branch.”

The mystery of the Bandra branch

DHFL’s most active branch in terms of value — the branch allotted the code (001) — was the one it maintained in Bandra, Mumbai. This single branch roughly made up a quarter of DHFL’s loan book, disbursing an average of nearly ₹1,000 crore a year for over a decade. It was arguably the most active home loan disbursal unit in all of India.

Only, it didn’t exist.

This branch was a fictional creation. It was a ghost that only existed as a logical module in the DHFL’s accounting systems. It ran as a parallel book of accounts, housing all of the company’s shady activity. It would cook up tens of thousands of fake loans out of thin air, and every month, those details would be mirrored into the company’s main accounting systems — so that they showed up in all its company-wide reports.

Most of this worked on the back of the accounting software, FoxPro, through a series of custom routines. They built a “Disbursement Distribution” code — which could break a single large payout into entries for thousands of small, fictional home loans. If any money came back, a “Collection Distribution” code would sprinkle it across all these fictional mini‑accounts. If it didn’t, a “Due Disbursement” code would “top up” the shortfall by booking a fresh “disbursement” of the pending amount, so that all those fictional accounts would look like they were making payments on time.

In short, the company had put together elaborate software plumbing to hide large, secret pay-outs as “affordable home loans”.

This would all link up with and consolidate into the company’s main systems, where they would be camouflaged among all the regular, legitimate loans the company was giving out.

Where the money really went

In the years between FY 2008 and FY 2019, DHFL’s Bandra branch gave out over ₹11,000 crore in actual money as fictional home loans, all masked through this sophisticated system. When you added all the fake entries the system masked, DHFL’s books showed nearly ₹22,000 crore in disbursements from the branch. It also recorded nearly ₹11,000 crore in supposed interest income. This was all, of course, a mirage.

But what was it hiding? Where was that money going?

SEBI found 87 different entities — which it called the “Bandra Book Entities” (BBEs) — that were at the other end of these transactions. Many of them had no assets, no revenues, and a negative net worth. And yet, they were loaned hundreds of crores. At least 83 of them, as far as SEBI could tell, were linked to the Wadhawan brothers and their relatives.

Naturally, none of those loans went through the standard underwriting and KYC processes. Instead, the company built a parallel flow for the Bandra branch loans. Whenever one of those BBEs would write to the company, asking for funds, it would be forwarded to the company’s Chairman and Managing Director, Kapil Wadhawan.

He would simply respond with “Approved”. Instantly, the company’s accounts department would make that money available for disbursal. This all happened with no checks, no collateral, no oversight, nothing.

A lot of this money would make its way back to the promoters. From the data available to it, SEBI was able to trace at least ~₹2,250 crore going into other companies that were connected to DHFL’s promoters and officials.

In the back-end, the company’s systems would chop these into tiny retail “home loans,” and start recording regular payments into those accounts — whether any money came in or not. This made the company’s books look artificially good. After all, at least a quarter of its supposed “loan book” looked pristine, with all payments coming in on time, like clockwork. Those fraudulent transactions, ironically, improved how DHFL’s published financials looked, helped DHFL raise more money, and let it justify AAA ratings.

There are some other tangents here that we aren’t going into — including a late attempt, in 2019, to clean up the Bandra branch’s debt. For that, we recommend diving into SEBI’s order.

SEBI’s case

A lot of what we’ve described so far was the gross mismanagement of an NBFC. That is the domain of the RBI, and indeed, it was the RBI that first took charge of the matter.

But SEBI also read it as a violation of securities law.

See, DHFL was a listed company. Both its shares and its debt were publicly listed. It was therefore bound by the high standard of conduct that binds any listed company. It had a duty to be truthful in its dealings, and give an honest account of itself in its financial statements. It was also required to clearly tell its investors of any related parties that it was transacting with. Any investor that put their money in the company — either its shares or its listed debt — was basing their investments on the company’s own public statements.

But not only was the company not forthcoming about its problems; it set up an entire system to manufacture transactions and avoid oversight. There couldn’t be a more obvious violation of those duties.

When the RBI had taken the company off its promoters’ hands five years ago, it was trying to correct the mismanagement of an NBFC. SEBI, this time around, was going after the company’s promoters and officials, essentially for duping investors.

For this, it has slapped them with a penalty of ₹120 crore. The Wadhawan brothers, as the masterminds of the scheme, will have to cough up the largest share — ₹27 crore each. The rest is distributed among the company’s other directors and executives. All of them have also been ordered not to approach the public markets in any way — including as a director or executive of any entity that has anything to do with the markets.

We know this seems rather small, given the scale of the operation, but do remember that this is only the direct penalty. SEBI will now separately try to quantify the illegal gains they’ve made from the markets, after which it will ask them to disgorge all of that as well.

The long shadow of a ghost branch

The Bandra branch story is, at its core, a reminder of just how banal financial deceit can be. We’ve covered many SEBI orders on The Daily Brief, where fly-by-night operators play with public greed to net a few crores. But this one — one of the biggest we’ve covered so far — wasn’t a single, dramatic rug pull. Instead, it was something altogether more boring; the quiet, relentless churning of a software-based accounting machine that was built to re-label reality. The company’s large, risky payouts, once they went through this funnel, came out as an immaculate portfolio of tiny, punctual home loans. All of them sat in the company’s published financials, right before the public eye, for over a decade.

On paper, DHFL looked like one of the safest businesses in Indian finance. But it was all a shell game.

To SEBI, episodes like this can call the integrity of our public markets into question. If a listed company can lie in its fundamentals for so long, and use those falsehoods to raise so much capital, who can trust where their money is going any more? That is the very basis of SEBI’s order.

The Bandra branch may have been a ghost in the system, but it casts a solid shadow over India’s financial markets.

India’s real estate sector: Three roads to one destination

Recently, we went through the basics of the (residential) real estate business, and everything that matters to a developer’s financial health. Now, we’re putting that knowledge to work. We're looking through the Q1 FY26 results of the residential arms of three listed real estate giants: DLF, Godrej Properties, and Sobha. All three, on the surface, do the same thing — building and selling homes across India. But scratch beneath that, and you see three very different ways of going about that work.

Through these results, we will see how those differences result in different outcomes — and how they create different vulnerabilities.

Three paths; one destination

The three companies we’re looking at today all have very different business models.

DLF, the oldest of the three, has been around for eight decades. It was founded a year before India got its independence, in fact. Over those long years, they accumulated vast land holdings — most of them right outside Delhi, in today’s Gurgaon, but some in other parts of North India and major metro cities. Back then, those land banks would have cost a fraction of today's rates.

As those cities grew, their land holdings turned into prime property. Some of that was their own doing — they practically created early Gurgaon, for instance. For years, they’ve dominated the real estate market of NCR. Recently, however, they’ve started looking outside their comfort zone. They just made their first serious move into Mumbai, and are looking to expand in Goa as well.

Godrej Properties went for a different route. Instead of straight up purchasing land, they decided to create a network of partnerships. They make deals with land owners, offering to develop their property in exchange for a share of the profits. This capital-light model lets them expand rapidly across multiple cities. In every city they enter, local partners bring land and local knowledge. Godrej just brings brand, execution, and marketing expertise. This lets them move quickly, without the massive upfront investments that traditional developers require.

Sobha, meanwhile, chose a do-it-yourself path. They don’t just develop properties — they make tiles and fixtures, train their own crews, construct everything in-house, and generally, control every step of the process. This gives them complete control over quality, bringing them a lot of trust. At the same time, it’s harder and more expensive for them to expand. They started in South India, but are slowly moving north. Last quarter, though, NCR contributed to 57% of total sales.

All three are making different bets about what matters the most in real estate. And the quarter gone by is a single snapshot into how those bets might play out.

Pre-sales

As we noted in our primer, one of the most important sources of money, for any real estate developer, comes from pre-sales — when people pay to book an apartment before it’s built. This is where all their strategy and marketing meets actual wallets.

DLF absolutely crushed the pre-sales game this quarter, with bookings of ₹11,425 crores — a staggering 78% jump from last year. Most of these were for high-end luxury apartments in the heart of Gurgaon — each of which sold for ₹7 crores or more. A single project — Privana North (Phase 3) — accounted for 96% of those bookings.

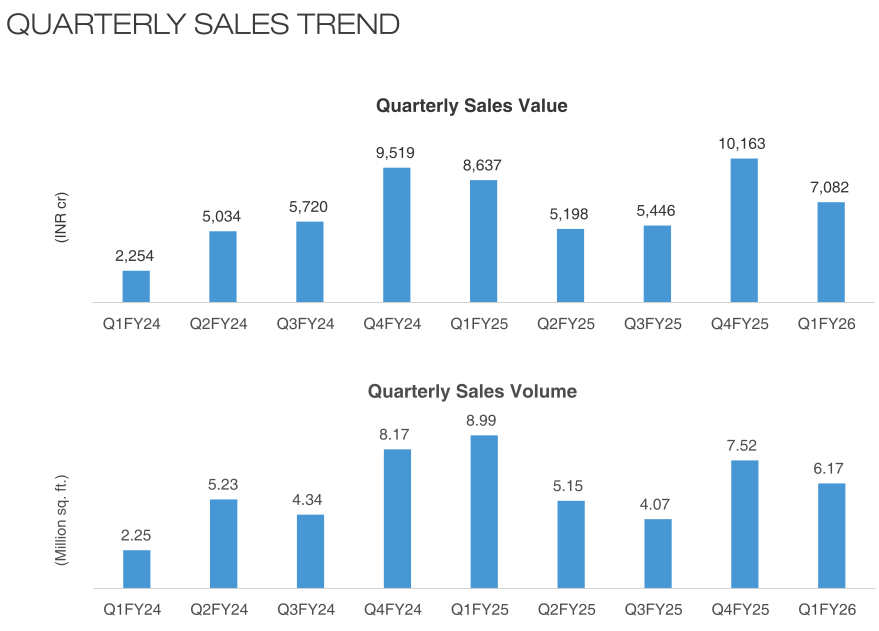

Godrej Properties brought in ₹7,082 crores in bookings. That was 18% below last year, but still marked the 8th consecutive quarter that they crossed ₹5,000 crores. The decline highlights a fundamental reality of this business: real estate is fundamentally lumpy. Unlike many other sectors, real estate companies don’t have a consistent stream of revenue. Everything revolves around how many projects you’re ready to launch.

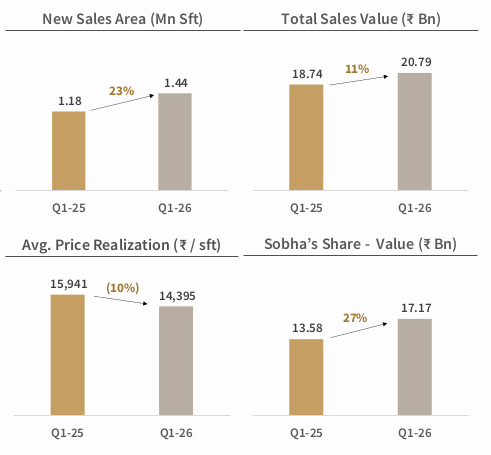

Sobha, meanwhile, raked in ₹2,079 crores in pre-sales — 11% over last year. This was a record quarter for the company, as it crossed the ₹2,000 crores in quarterly sales for the first time. Dig one layer deeper, though, and it seems like their average price per square foot dropped 10%.

Is that a reason for panic? We aren’t sure. In Q1 last year, almost half of Sobha's sales came from expensive homes worth more than ₹5 crores. This year, their biggest sales chunk came from cheaper ₹2-3 crore homes. If you've launched cheaper projects in a quarter, your average price naturally drops. But that doesn’t, in itself, tell you much about the company’s prospects.

Collections

At the end of the day, pre-sales numbers are a marketing victory. It’s when you make collections that those actually become cash in hand. That conversion isn’t automatic — in real estate, customers don't pay everything upfront. They typically pay up in installments that are tied to construction milestones.

The rate at which you can do so is your “collection efficiency” — the share of a quarter’s sales that you actually collect in the same period. It’s shaped by many factors: the terms you set, the progress you’ve made on projects, prevailing market conditions, and more. Together, these determine how much cash you actually have at your disposal.

In contrast to its impressive pre-sales figures, DLF actually collected just ₹2,794 this quarter — a collection efficiency of roughly 24%. That’s exceptionally low — ordinarily, such low figures would be a red flag. But there’s some nuance here — almost all of DLF’s fantastic pre-sales came from a brand new launch. The launch received a blockbuster response, but customers have probably actually just paid their initial down payments so far.

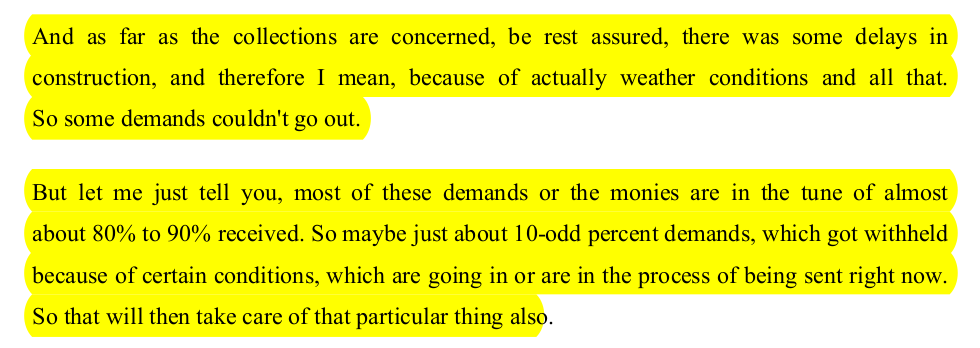

The company also ran into some weather-related delays, and didn’t send out demands to its customers. That will probably sort itself out soon.

According to DLF’s management, where they did ask for money, 80-90% of that money came in. So its poor collections may be a mix of timing, a bumper response to a new project, and bad weather. Here’s what its management said:

Godrej Properties achieved a healthier — but not spectacular — 52% collection efficiency this quarter, collecting ₹3,670 crores against their sales. That said, the company supposedly receives ~94% of payments within a month of sending out an invoice — indicating that their collections process, at least, is fairly healthy.

Sobha, in contrast, achieved the highest collection efficiency of the three, at 77% — raking in ₹1,599 crores. The company has a range of projects that are at different points in their lifecycle, and its collections give it a steady inflow of money to complete them.

Execution

Ultimately, though, what people are paying a developer for is execution. While pre-sales and collections tell you how well prepared a company may be for future projects, its execution track record actually give you a picture of how well it comes through on its past promises.

DLF had some good news on this front. It managed to get occupancy certificates for major residential projects, like OMT Delhi, or Garden City Enclave in Gurgaon. After years, those customers are finally getting the keys to their apartments, and the revenue cycle for those projects shall come to an end.

But not everyone had the same luck. As we noted in our primer, bringing a project to the finish line can be a real nightmare. Take Sobha. It had five projects in Bengaluru that were completely built and ready to hand over. Only, they couldn't get occupancy certificates. All that revenue was stalled. And that was a big hit for the company, as we’ll soon see.

Godrej didn’t talk about completions this quarter. But their cost-of-construction spending increased to over ₹1,170 crores in the quarter. That is, there’s probably a lot more construction activity within the company. What that has resulted in, however, we have no insight into.

The Margin Story

With that out of the way, let’s turn to the bottom line.

DLF's gross margins took a hit this quarter, dropping to 39%. This wasn't because they suddenly got bad at construction, of course. It’s just that quarterly profits and losses can be convoluted in this industry. This quarter, the company finished off lower-margin projects, which dragged down their figures.

DLF also has a rental business, which makes assessing profits a little confusing — but that’s outside the scope of what we’re discussing here.

Godrej did better — with gross margins of 58%, and an impressive PAT margin of 37.5%. That’s well above the industry standard. It’s also an illustration of how its asset-light business model works. One of the biggest expenses, for a real estate company, is to amass land. That is something Godrej skips entirely — working with landowners instead of buying that land. That makes for better margins, although its rivals make better gains over the lifetime of a project.

Sobha, in contrast, faced the quarter's biggest margin challenge. EBITDA margins collapsed to just 8.1% and PAT margins at a mere 1.5%. Because those five projects in Bangalore were stuck, ₹650 crores in revenue ₹150 crores in PAT and that should have shown up this quarter just... didn't. Meanwhile, its expenses keep ticking. Here’s what its management said:

This is an illustration of the perils of Sobha's approach.

Ordinarily, their vertical integration gives them a lot of control over quality and timelines, since they aren’t juggling multiple contractors. On the other hand, when something goes wrong — even something outside their control — it hits them harder. Their attention, and therefore their risk, is concentrated in a small set of projects. Others, who manage a range of projects through an army of sub-contractors, are more diversified.

Cash flows

To a real estate company, though, profits and margins are arguably less important than cash.

See, there’s a lot of complexity in how a real estate company recognises revenue. Often, profits on paper don't translate to money in the bank. A company might show impressive profits and be cash-starved. It might report weak earnings while sitting on piles of money. That's why it helps to look at “operating cash flows” — the actual money that companies actually have available to fund their next round of land acquisitions and construction.

This quarter, all three companies had a net positive operating cash flow — that is, all three collected more money than they spent on their business. Their debt levels were also manageable. Put the two together, and all three companies have enough financial firepower to keep funding their projects.

DLF, for instance, generated ₹1,420 crores in extra cash. Godrej achieved ₹947 crores, although that is down 4% from last year. Sobha generated ₹395 crores — up 22% from last year — which means that their poor profits didn’t hurt the actual money they have in hand.

This is the sweet spot for any developer: if you can constantly spin off more cash than you spend, you can keep constructing more.

What’s ahead?

You can think of a real estate company as an unending capex machine. Unlike the average company, that might announce expansions once in a while, a real estate company’s upcoming projects is everything. Those plans are not an indication of upcoming capacity, but their main product. Even the most successful real estate company could die if it doesn’t have new projects ready to launch over the next 2-3 years.

DLF has perhaps the strongest pipeline visibility. It’s coming up with 37 million square feet, potentially worth ₹1,14,500 crores. Their massive land bank gives them decades worth of opportunities ahead, and they plan to use this to launch more luxury and super-luxury properties.

Godrej Properties added 5 projects worth ₹11,400 crores in potential future sales — more than half their annual business development target achieved in just three months.

Sobha has 17.67 million square feet lined up across 17 projects, with plans to launch 6-8 million square feet in the next nine months.

But at the end of the day, having a pipeline is one thing. But turning those plans into actual apartment keys in customers' hands is where the real test begins. Only time will tell whether this potential will turn into successful launches without delays.

Tidbits

After losing some Axis and ICICI lounge programs, DreamFolks is shifting gears. The travel and lifestyle aggregator is now eyeing faster growth in non-lounge services — from golf and members-only clubs to dining, spa, wellness and even social club access — while expanding into South East Asia and the Middle East.

Source: Business Line

Just a month after temporarily banning the U.S.-based Jane Street for index manipulation, SEBI has proposed to formally bring algorithmic trading and proprietary trading under its master regulations. The draft also suggests removing the outdated definition of “small investor”, citing SEBI data that 91% of retail traders lost ₹52.4 thousand crore in derivatives in 2024

Source: Reuters

In a step forward for the nuclear sector, India plans to lift its state monopoly on uranium by allowing private companies to mine, import, and process the fuel. This landmark move—key to tripling nuclear power capacity by 2047—retains state control over spent fuel reprocessing and plutonium management.

Source: Reuters

S&P Global has upgraded India’s long-term sovereign credit rating from 'BBB-' to 'BBB', citing the country’s strong economic resilience and steady fiscal consolidation, and has maintained a stable outlook. The move reflects enhanced investor confidence in India’s macroeconomic fundamentals and fiscal discipline.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Prerana

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Understanding long legal orders is tough.The Daily Brief by ZERODHA does small investors like me by gist of SEBI order and explains The Bandra branch story in simple to understand terms.The Daily Btief’s observations are key lessons for bankers,entrepreneurs,corporate executives,and even for investors that how banal financial deceit can be.

It reminds me of Satyam saga,Harshad Mehta scandal etc and once again shows what greed/dishonesty does to systems.

The other coverage on RE is very relevant,more so,it appears there’s no tmrw for RE cos.

As rightly analysed by The Daily Brief,the 3top cos are following One Path—Luxury RE and are thriving because of the wealth inequality.For most rich,owning a property is a “cornerstone of wealth strategy,”and many own six or more homes—homes they don’t use and common people suffer as by buying (hoarding)by rich,makes homes unaffordable.And,surprisingly the rich are rewarded by appreciation and rental income and that creates contagious FOMO.

India’s uber-rich — defined as the top 1% of Indian households, or individuals earning the top 40% of income — held on to $11.6 trillion or 59.1% of all assets held by Indian households, according to data from investment house Bernstein.

Of this, $7.1 trillion, or 61.2%, is parked in real estate and gold, the same report indicated.

True to the famous quote by Mark Twain—"Buy land, they're not making it anymore." Rich and poor Indians have historically relied on physical assets.

The Daily Brief analysis evidences the urgent need of affordable housing that these Top cos are not making.Why !

We had invested around 10 lakhs in DHFL FD through an agent. It was AAA rated at the time. Everything was going nice but one day the rumours came out about some fraud. We submitted fd for premature withdrawal and received full money. Got lucky as that was the last day they released fd amount. From next day nobody got anything. I think total 5000 cr was still pending the last time I checked. The point is it’s difficult to trust rating agencies. How did they not know about this fraud when it was going on for such a long time?