Everything you need to know about the budget

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The Daily Brief budget breakdown

The Daily Brief budget breakdown

The budget is an exercise with many goals.

It is, at one level, an exercise in accountability; where the government puts its finances forward, giving the country an opportunity to take a long, hard look at how our money is being managed. It is also a constitutional exercise, where the government asks the parliament’s permission on how it plans to raise money, and spend it. To that end, it is a strategic presentation; the government indicates what its priorities are, what it will commit money to, and how that money could help achieve those priorities. All of this is wrapped in a public communication exercise; the budget is the most important public statement on the government’s economic performance, goals, and plans.

There are, in short, many different ways of looking at the budget. And if you’ve been following the news over the last twenty-four hours, you’ve probably seen them all.

At The Daily Brief, we wanted to look at the budget in three ways. To begin with, in our minds, you can only understand a budget within a wider framework — of how money moves through the system. To that end, we begin by digging into the public accounts themselves. Next, we look at how the government is changing its taxing decisions, and by extension, the incentives of everyone in the economy. Finally, we wanted to leave you with what are, to us, the most consequential policy changes that the government has signalled.

Behind our public accounts

This budget comes in a trying time, at a moment when the global economy is fraying. That’s why it is trying to do three things at once. One, it is trying to keep capital spending going — making enough future-oriented investments for our economy to maintain its upwards trajectory. At the same time, it’s trying to slowly bring down how much India borrows. And finally, it wants to have the flexibility to spend more if the moment calls for it.

In essence, the goal is to spend less, but spend better. This is a difficult balance to maintain.

How realistic does this agenda seem? How do we get there? To answer that, let’s take a tour through the government’s accounts.

How the government earns

A government is funded, first and foremost, by its taxpayers. This is its financial backbone; the most durable source of its funding. Ideally, this taxpayer money should anchor the lion’s share of its spending.

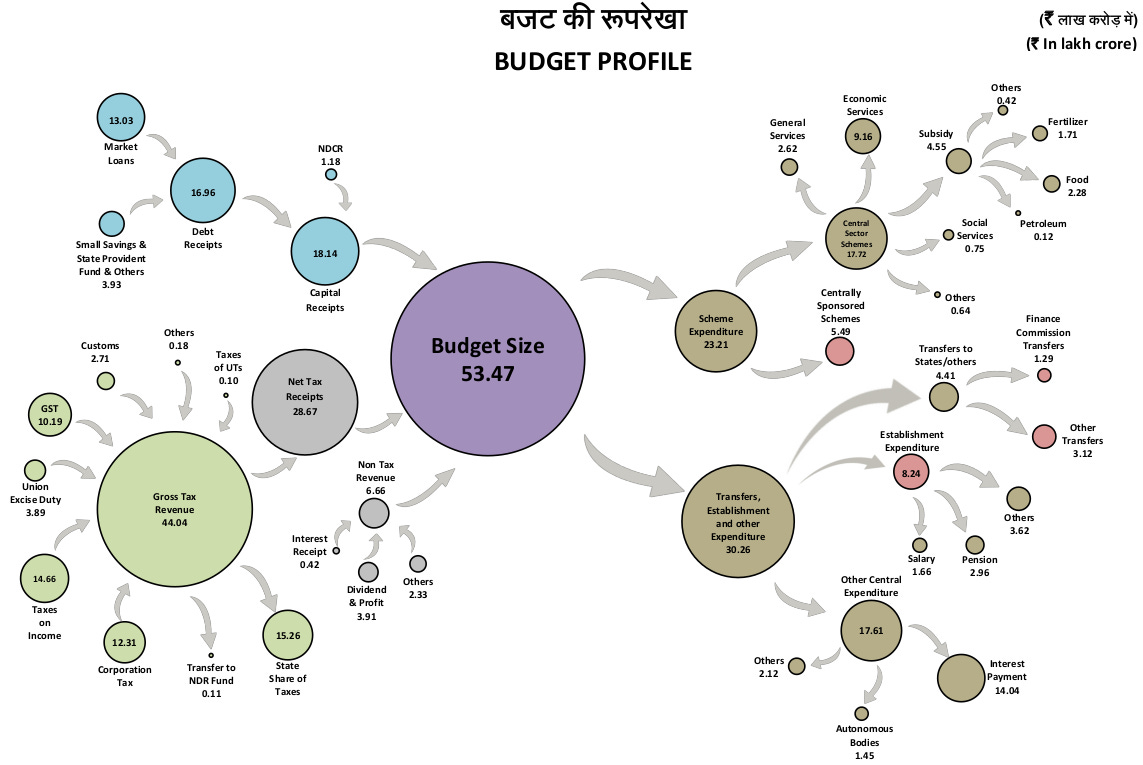

In the coming year, the government targets over ₹44 lakh crore in taxes. Meeting this target, however, is easier said than done. Last year, its targets were lower, at ₹42.7 lakh crore. In reality, though, it will probably fall short of that target by just under ₹2 lakh crore. That isn’t an insignificant sum — it’s a shortfall of over 4.5%.

What went wrong?

Over the last year, the government announced two major tax cuts. First, in the last budget, the government brought major changes to the tax structure. Effectively, if you were a salaried employee under the new regime, you would only have to pay tax if you earned over ₹12 lakh a year. The hope, perhaps, was that a more attractive tax regime would make people more willing to comply with tax laws.

Only, the government’s accounting was not conservative enough. It hoped to bring in ₹13.6 lakh crore in personal income taxes. The amount it actually thinks it will earn, however, falls short by over ₹1 lakh crore — a dip of more than 8%.

The other big change came later in the year, in the form of a massive rationalisation of GST rates. Many tax slabs were reworked. It almost completely did away with its “GST compensation cess” — an additional tax that was meant to reimburse state governments. Naturally, that meant the GST rates the government had budgeted for were completely off. And while this did, by all accounts, push up how much people were willing to spend, all that extra spending didn’t really make up for the government’s tax shortfall.

In all, where the government hoped to earn ₹10.1 lakh crore in central GST, it’s on track to ₹50,000 crore less. As the GST compensation cess effectively froze, the government will likely earn ₹80,000 crore less than it accounted for.

This isn’t to say there were no positive surprises over the year. The government will probably earn a tidy surplus in other places — corporate tax, excise duties and custom duties. This could stem the fiscal bleeding a little.

If the government is to meet its ₹44 lakh crore target in the coming year, however, it needs better tax collections across the board. Its income tax and GST revenues need to be in line with what it had budgeted last year, rather than what it’s actually on track to earn. It also needs to improve its performance on corporate taxes, and excise and custom duties. In all, it needs its tax collections to grow by 8% over this year, for its estimates to actually work.

Taxes aren’t the only ways in which the government earns, however. There’s a broad spectrum of other sources where it makes money: everything from license payments, to PSU dividends, to railway tickets. At our current pace, this year, these earnings will probably be much better than we had budgeted for a year ago. This could go some way in blunting the effect of our tax shortfall. The government’s non-tax receipts, at almost ₹11 lakh crore, are estimated to be more than 10% better than we first imagined — a difference of over ₹1 lakh crore.

Broadly, there are two main factors behind this bonanza. For one, its telecom revenues are on track to be more than double what was first accounted for: perhaps because of last year’s tariff hikes. At ₹1.77 lakh crore, they will net the government 115%, or ₹95,000 crore, more than expected. The other is the record dividends from this year. The RBI, in particular, paid the government an all-time high ₹2.7 lakh crore last year. Collectively, dividends gave the government an additional ₹50,000 crore over what it anticipated.

What the government spends

A lot of the tax the central government earns rightfully belongs to the states. Accounting for that, the central government’s “revenue receipts” for this year were roughly ₹37.8 lakh crore. In the coming year, it hopes to increase those to ₹39.5 lakh crore. This is, rightfully, the central government’s spending arsenal. For anything above this, it will have to borrow money.

What, in comparison, does it spend on?

Interestingly, there are large parts of the government’s spending where it has no room for discretion. For instance, the government has taken substantial loans over the years, for which it has to pay interest. This interest itself is a massive sum — to the tune of ₹14 lakh crore. That is roughly one-third of the government’s recurring expenses.

There are many other such heads. The day-to-day running of our military, itself, will cost ₹3,7 lakh crore over the next year — even before we think of modernising our equipment. Government pensions will cost ₹3 lakh crore. Running our food subsidy programs will cost ₹2.3 lakh crore. Central police forces add another ₹1.5 lakh crore to the government’s bills. And so on.

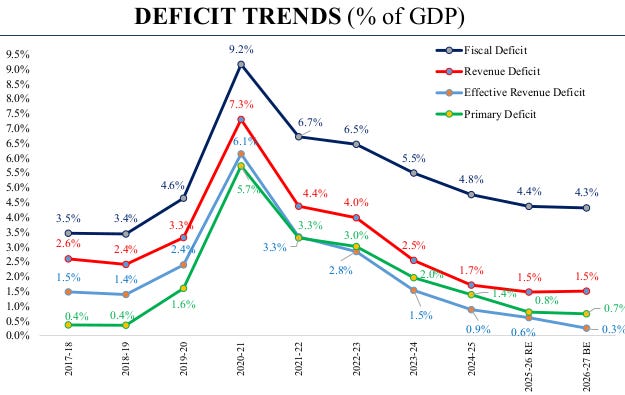

Effectively, in running the government, only counting business-as-usual costs, the government already spends roughly ₹1 lakh crore more than it earns — what it calls its “effective revenue deficit”. In other words, to make ends meet, the government spends ~0.3% of our GDP more than it has.

Changing this is possible, but it is usually controversial. Take the new VB-GRAMG scheme, which replaces the MNREGA. Among other changes, the new scheme pushes a lot of the financial risks from guaranteeing rural employment to the books of state governments. That has allowed the government to slash its budgeted expenditure under the scheme massively — to ₹44,000 crore, or little more than one-third of what it is on track to spend this year. But changes like this are hard to make.

That means everything a government really wants to do — all of the year’s discretionary “government policy”, or the kind of thing the Finance Minister’s speech focuses on — lies on top of that. Structurally, this has to be on borrowed money. It’s critical, therefore, that this extra spending is sensible.

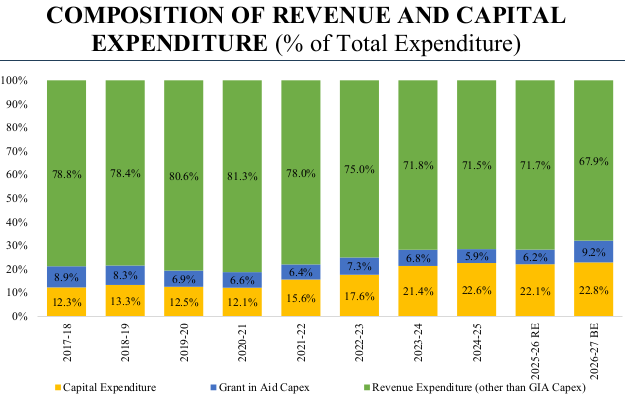

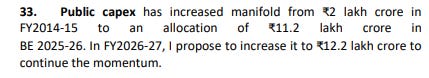

Over the last few years, the government has trained its focus on boosting capital expenditure. This is money that is meant to create future assets.

There are two types of spending that the government considers, collectively, as its capital expenses.

One, it makes investments itself. Last year, it planned to spend ₹11.2 lakh crore in this manner, with its actual expenditure coming down a notch to just under ₹11 lakh crore. Some of this was the classic sort of asset creation — building highways or railways. Some was spent on defence procurements — boosting hard power, though not economic power.

But there are sums where the future returns aren’t as clear. Take investments into shares of public sector undertakings, for instance. Or loans made to states and union territories. Some of that money, to be fair, will still go into creating assets. States, for instance, might borrow money to build infrastructure. As might PSUs; BSNL, for instance, spent large amounts of money upgrading large parts of its network to 4G last year. But the specifics, in these heads, aren’t very clear to us.

In the coming year, the government plans to boost direct capital expenditure to ₹12.2 lakh crore.

In addition to this, the government also gives the states additional grants — which are tied to their capital spending. In a roundabout way, this capital spending is effectively sponsored by the centre. Last year, it budgeted nearly ₹4.3 lakh crore, although it’s only on track to disburse ₹3.1 lakh crore. This year, it’s stepping up these grants slightly, to just under ₹5 lakh crore.

How do we afford this all?

This is all a lot of spending. Enough, in fact, that it outpaces the government’s revenues considerably. Last year, that created a deficit of ₹15,6 lakh crore. In other words, the government’s earning shortfall, itself, was 4.4% of India’s entire GDP.

A deficit, by itself, is not a sign of fiscal recklessness. Developing economies routinely run deficits to fund growth. They borrow to expand capacity, so that their future incomes rise. Tomorrow’s higher incomes, in theory, will then pay for today’s spending. As long as our economy grows faster than the cost of borrowing, it should be able to stay on top of its interest payments.

But this logic has limits. As we’ve seen, India’s interest burdens already make up a large share of its revenue. This is why, in 2003, India passed the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, which set targets for the amount of debt we could take. Over the long term, the hope is that we find a “glide path” that brings the government’s deficit to under 3% of GDP. Besides, in any year, the central government’s total debt load should ideally come down to ~40% of GDP.

So, how close are we?

In the coming year, the government has budgeted for a deficit of just under ₹17 lakh crore. This is based on an optimistic tax collection target, which is necessary to offset spending bills that are, to a great extent, locked in. In fairly sunny conditions, that is, we plan to borrow at least ₹1.37 lakh crore more than this year.

As the government puts it, this is 4.3% of our GDP, which is marginally better than our deficit this year. But that assumes that our nominal GDP will grow by 10% in the coming year. For context, it grew by just 8% this year. If we don’t grow faster, we have a longer, more meandering path towards fiscal stability ahead.

There are different ways to see this burden.

There’s an optimistic lens: the effective capital expenditure the central government expects is roughly the same as it expects to borrow. In that telling, we’re borrowing almost entirely to fund future growth. Seen this way, our borrowing looks good.

There’s a less happy lens too, though. Most of our borrowing simply atones for the sins of our past. ₹14 lakh crore of India’s finances, next year, will go into interest payments alone. That is, for every rupee we borrow, 83 paise shall go into paying off old loans. In this telling, we seem to be digging ourselves deeper into a hole.

Which is the better lens to take? Maybe we’ll only know after the fact, when the economic history of our era is being written.

This budget in taxes

With that out of the way, let’s look at the big tax changes this year.

To begin with, personal income tax rates, themselves, are unchanged from last year. What has changed, though, is the legal backbone of the tax system. From 1 April 2026, India will move to a new Income Tax Act, replacing the old 1961 law. A large chunk of this year’s “tax amendments” are technical clean-ups — like adding missing definitions, correcting section references that pointed to the wrong clauses, and tightening language, so the new Act behaves the way it was meant to.

Where this Budget does make its presence felt, however, is in the capital markets — especially derivatives. The market was clearly unhappy.

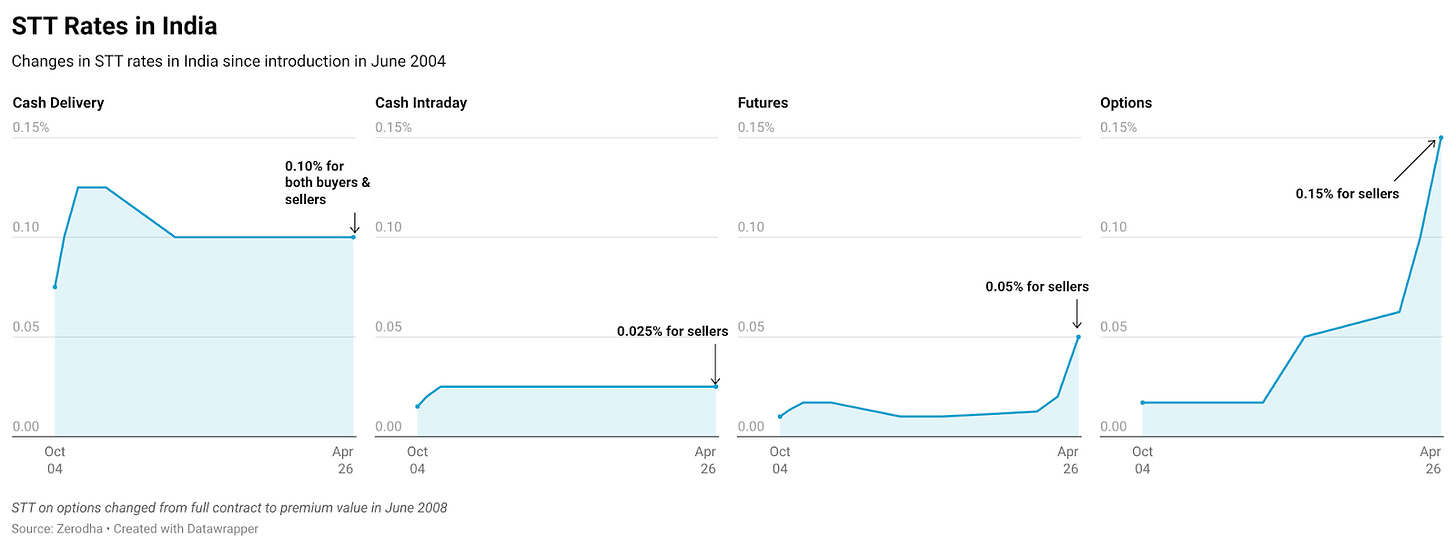

Every time you trade certain securities on an exchange, you pay a Securities Transaction Tax, or STT. This year, the government has raised STT across futures and options — in a move that echoes what it did what it did two years ago.

Here’s how the new STT rule works. If you sell a future, the tax you pay is now increased to 0.05% from 0.02% — a 150% increase. And the tax on selling options has gone up from 0.1% to 0.15% of the premium — a 50% increase. If you exercise an option at expiry, the STT is going to be 0.15%, from 0.125%.

The distinction between “selling” and “exercising” an option is important. When you sell an option, what’s being traded is the premium — the upfront price of the option contract. STT in that case, is charged on the premium amount. When an option is exercised at expiry, on the other hand, the premium is no longer relevant. What matters then is the option’s intrinsic value — how much it is “in the money”. So, the STT on exercised options is charged on that intrinsic value instead.

In effect, the budget raises the cost of trading across the board, making high-turnover derivatives more expensive at the margin.

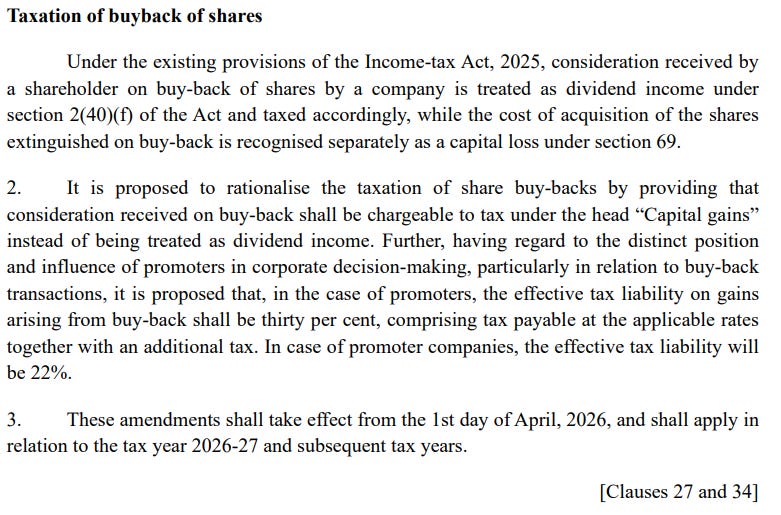

The next change that has happened is in how share buybacks are taxed.

Since the 2024 budget, buyback proceeds were treated in a slightly awkward way. Beginning with that year, the cash you received from a buyback was taxed like your dividend income, at income tax slab rates. Meanwhile, the cost of your shares sat separately as a capital loss. This capital loss could be adjusted against any capital gains.

This was a convoluted system, and the new budget simplifies that treatment. Buyback proceeds are now taxed as capital gains — you take what you received, subtract what you paid for the shares, and tax the difference.

There is, however, a clear distinction for a company’s promoters, because they get a say in whether and when a buyback happens — opening the doors to misuse. And so, the Budget introduces an additional tax layer for them. And so, promoter gains from buybacks are taxed at an effective rate of 22% for corporate promoters and 30% for non-corporate promoters.

For ordinary shareholders, the new change is mostly for clarity. But for promoters, it is also about limiting tax arbitrage.

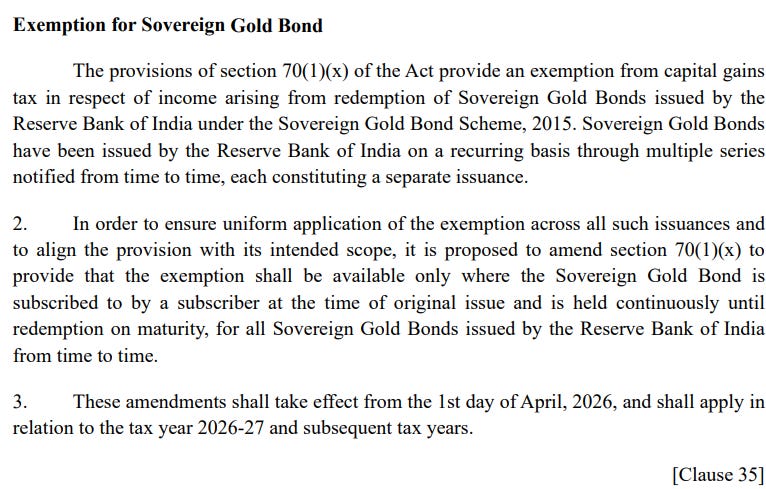

Then, there are changes to how Sovereign Gold Bonds (SGB) will be taxed. They continue to enjoy tax-free capital gains on redemption, as they were before. But the Budget makes one important clarification, which effectively reduces who can avail that benefit. The exemption is now explicitly limited to investors who subscribed to the bond at the time of original issuance and held it continuously until maturity. So, if you buy an SGB from the secondary market and later redeem it, your gains will be taxed like any normal capital gains.

Now, onto money going out of the country.

The Budget tries lowering the friction on outward remittances. To be clear, it doesn’t change the final tax burden. But it reduces how much tax will be collected at the source, when a transfer is being made. TCS rates have been reduced to 2% for education and medical remittances. Overseas tour packages, too, are now subject to a flat 2% TCS, irrespective of the amount. Since TCS is usually adjustable against your final tax liability, this mostly affects cash flow, rather than your tax burden. Less money gets locked up upfront when you pay fees or book travel abroad.

Finally, on the indirect tax side, there’s a big consumer-facing relief. The tariff rate on dutiable goods imported for personal use has been reduced from 20% to 10%. This applies to individuals bringing goods for personal consumption. This reflects a recognition that not all imports are commercial, or deserving of a high duty wall.

The big policy moves

Finally, let’s come to the big policy announcements from the Finance Minister’s speech that got us excited.

Takeaway #1: Who wins, who loses

In our first takeaway, we got a sense of what kind of manufacturing India wants to prioritize.

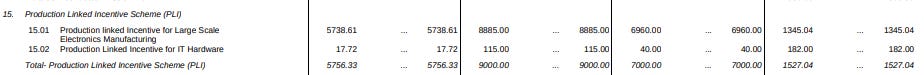

Take electronics, a huge winner in this budget. The government is trying to move from mere assembly of devices to making the parts that go into phones: like capacitors, camera lenses, PCBs, etc. That shows up in how its allocation of older PLIs has reduced significantly from last year’s Budget, as those schemes have matured.

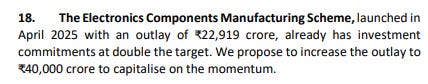

At the same time, the outlay for electronics components has been raised by ~75% to ₹40,000 crore.

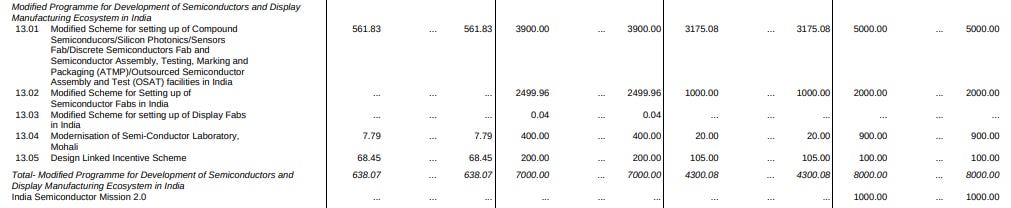

With the advent of AI, India has also made allocations to high-tech sectors. For instance, the Budget makes room worth over 8,000 CR to develop semiconductors. The Budget also provides tax holidays to foreign companies setting up data centers in India.

Pharma is yet another bright spot. The government launched “Biopharma SHAKTI”, a ₹10,000 crore scheme to promote biologics and biosimilars. On The Daily Brief, we’ve covered how biologics are far more complex than the generics we’re known for exporting. Much like electronics and data centers, making biologics is a capital-intensive process.

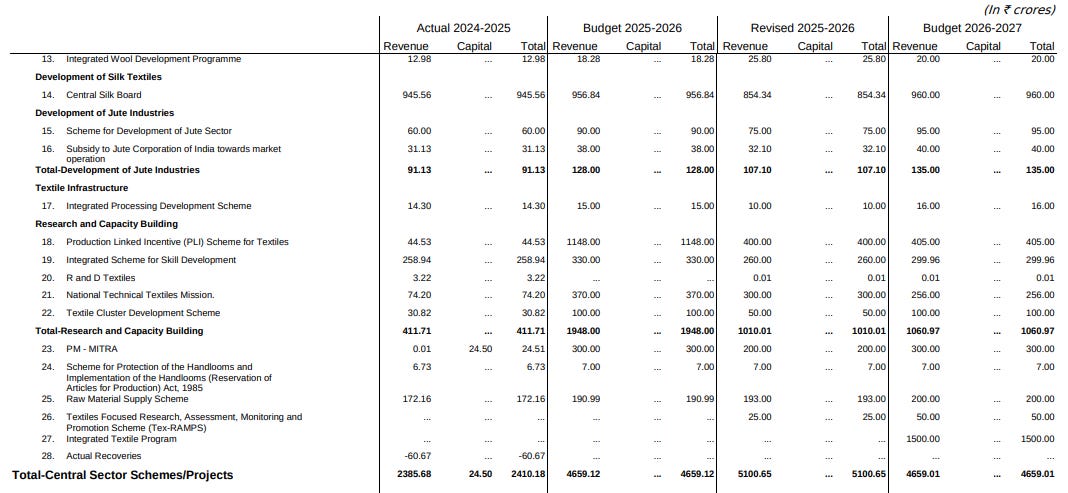

In contrast, though, labor-intensive sectors like textiles and apparel have slipped down the priority list. For instance, while the Budget has announced many schemes to promote textiles, this year’s capital outlay for the Ministry of Textiles has remained somewhat flat compared to last year. Moreover, the PLI scheme for textiles has also had a lackluster performance.

For many countries, making textiles has been a stepping stone to large-scale economic development. While still quite globally competitive, Indian textiles lag behind countries like China, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Prioritizing capital-intensive sectors usually leads to economic growth with slower employment expansion.

Takeaway #2: Crowding-in?

Our second takeaway is about how the Indian government is trying to convince private investors to follow India’s public capex.

As we’ve mentioned above, the government has, in recent years, made capital spending a priority. One of its biggest new projects is the announcement of 7 high-speed rail projects connecting metros and tier-1 cities.

Such capex aims to absorb early risks in long-term infrastructure projects, so that private capex feels comfortable chipping in. However, as we’ve covered before, the private sector has responded quite sluggishly to government nudges. So, the Budget has introduced new mechanisms to make these projects more investible.

One such tool is the Total Return Swap (TRS). See, corporate bonds are often used to raise funds for long-term projects, but investors sometimes don’t like them because of their long time horizons and risks. The TRS allows investors to gain or hedge exposure to corporate bonds without directly owning the bond. India will also improve investor access to derivatives based on the corporate bond market.

The Budget also created an Infrastructure Risk Guarantee Fund. It aims to provide partial guarantees to lenders of infrastructure/construction loans. This would help in cushioning early-stage construction risks for private developers.

Taken together, these measures signal an attempt to shift risk away from banks and toward capital markets. Bank deposits have much shorter maturities than 10–20 year infrastructure projects, making banks ill-suited to carry such risk at scale. Corporate bonds, however, are better suited to infrastructure financing as their maturity periods match.

Takeaway #3: Moving goods

The budget treats logistics and transport as a binding constraint on our manufacturing and exports.

Our costs of transporting goods and minerals — both within and outside our borders — are higher than our peers like China and Vietnam. And all sorts of things can become a chokepoint. A few years ago, for instance, the world suffered from an acute shortage of shipping containers that slowed global trade.

The budget’s large infrastructure push aims, in part, to solve these bottlenecks. For instance, the government announced a new Dedicated Freight Corridor connecting Dankuni (in West Bengal) to Surat, Gujarat. This corridor will cover India’s East-West cross-section, connecting mineral-rich areas to industrial hubs in a cost-effective manner. At the moment, India has two functional corridors and 3 more planned ones.

This has contributed to the increase in Railways spending. As per the National Rail Plan, the government aims to increase the modal share of rail in India’s total freight movement to 45% by 2030.

Another important scheme is the new ₹10,000 crore outlay to manufacture our own containers. As India signs a flurry of trade deals with other countries, we’ll need to have plenty of our own container capacity.

Takeaway #4: Critical minerals?

Lastly, the Budget makes plenty of room for rare earths and critical minerals. The government is creating four Rare-Earth Corridors that span 4 states: Odisha, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

These states were chosen in particular because of their long coastlines. After all, critical minerals are often found in the monazite sands that line the beaches of peninsular India. However, they’re often found alongside a radioactive material called thorium — which the government guards strongly, because of its atomic energy potential. Could these special corridors help ring-fence this hazard?

Perhaps, this is also connected to our logistics push. The Budget’s plans for new rail freight corridors and inland waterways often involve Odisha, which houses many of these minerals.

But beyond that, the government has also introduced new incentives to encourage participation in minerals that we need for making EVs, solar panels, and other new-age technologies. Some of them are as follows:

The basic customs duty on monazite has been reduced to zero

This Budget also includes critical minerals in Schedule XII of the Income Tax Act — which allows companies to claim tax deductions on expenses incurred during exploration and mining

The customs duty on sodium antimonate, a key raw material used in making solar glass, is proposed to be removed.

But, as we’ve covered before, mining in India isn’t difficult just because the incentives aren’t big enough. Those problems, it seems, haven’t yet been addressed in the Budget.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie, Krishna, Kashish, and Pranav

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

What a fantastic way to explain complex concept. Thanks.

Just a request since many of us are new to this investment stuff we get confused and baffled with the so called finfluencers who are mostly short sighted and views driven. Kindly make a series where you explain sectors overview as how to look any sector so that any news would then make sense and make us think larger picture. TIA