India, Europe, and the art of the deal

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India and the EU strike a heavy-duty deal

India’s electronic future lies in its trash

India and the EU strike a heavy-duty deal

“The mother of all deals” is finally approved.

After years of negotiations, India and the EU have finally signed a free trade agreement covering nearly 2 billion people. It’s the largest trade deal for either side.

The timing couldn’t be more consequential. Both entities, while at different stages of economic development, find themselves squeezed between the two great powers of the world.

On one hand, the United States is playing bullyball, slapping 50% tariffs on many Indian goods. Europe, meanwhile, has been threatened with additional levies if they don’t meet Trump’s demands on Greenland. At Davos recently, US officials openly berated the European economy. All of this has left the Europeans disillusioned with their long-standing ally.

On the other side lies China. With how it weaponises global trade, both entities find China too unreliable a trade partner. The EU is worried about Chinese goods evaporating their industry. Our own relationship with China is colored by a long history of conflict.

In this context, more than ever before, hedging against the great powers is something India and Europe now see eye-to-eye on. In fact, Europe views us as perhaps the only significantly-sized alternative to China.

But India-EU ties haven’t always been smooth. Negotiations for an India-EU trade deal began nearly 20 years ago, but stayed in limbo due to differences they couldn’t settle. So, how did two sides finally find common ground this time?

An underperforming relationship

Before we get to what went wrong, let’s look at what India and Europe actually trade with each other today.

The India-EU trade relationship looks strong on paper. As of FY25, bilateral goods trade between both entities stood at $136.5 billion in FY25.

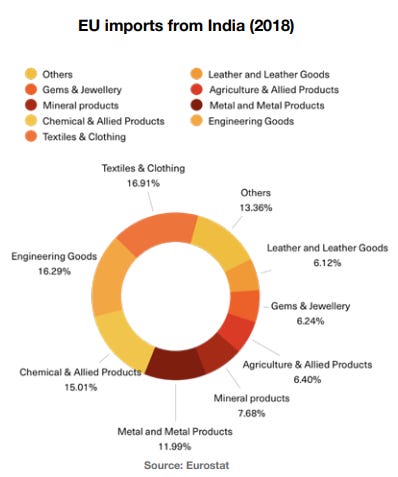

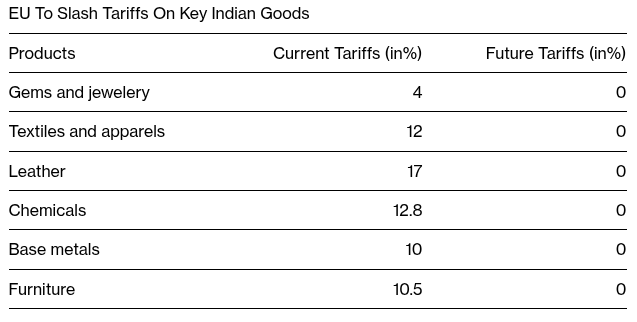

The composition of trade reflects each side’s strengths. As a whole, the EU is India’s largest importer currently, making up 17% of India’s total exports to the world. India ships textiles, apparel, chemicals, petroleum products, medicines and gems to Europe. Many of these are labor-intensive manufacturing goods, but we also export plenty of services (like IT, consulting, etc) to the EU.

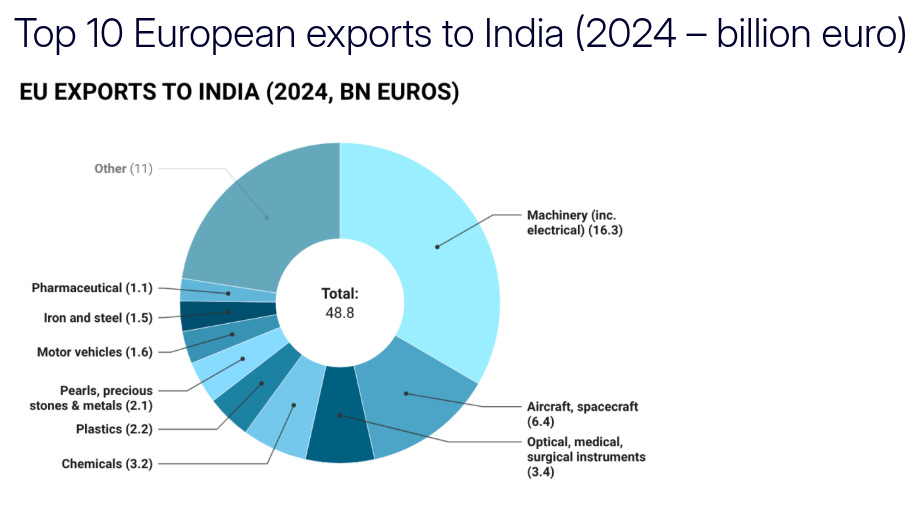

Meanwhile, from the EU, we import machinery, aircraft, transport equipment, and drugs, and even cars. A lot of these are capital-intensive goods.

However, despite this huge volume of trade between them, both sides have long viewed this relationship as underperforming.

Here’s the problem: India is only the EU’s 9th-largest trading partner, accounting for just 2.4% of the bloc’s exports. Compare that to the US at 17% or China at 15%. For a country as big as ours, India has punched well below its weight in European markets. The same is true of European firms in India.

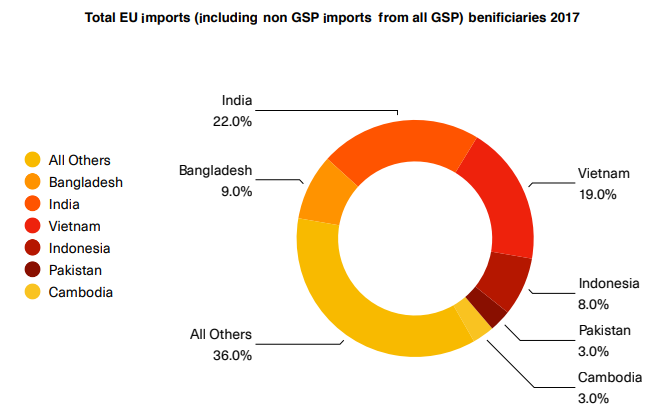

Without preferential access, both sides are losing ground to competitors who had it. Vietnam and Bangladesh, with their own trade deals, have been eating into India’s share of European textile imports. All the while, European machinery makers and auto players watched Korean and Japanese rivals — armed with FTAs with India — gain ground in India. The relationship was large, but was slowly bleeding market share to everyone else.

Moreover, despite being India’s largest trading partner, the EU’s own investments in India were less than half of what they invested in, say, China or Brazil.

Behind the inertia of this relationship is a long, hard negotiation on trade terms that goes all the way back to 2007. By 2013, after 15 rounds of negotiations, neither side had moved enough, unwilling to make compromises. The talks were stalled then, and the relationship drifted.

The stalemate

To understand why the negotiations went awry, what helped us was a simple lens: one of sovereignty versus complementarity. This framework won’t help you decide right or wrong, but just how nations think about trade.

Every trade negotiation involves this tension. Trade complementarity is straightforward — you have something I want, I have something you want, let’s trade. For instance, India makes textiles cheaply while Europe doesn’t, and wants cheap textiles. Europe makes precision machinery that India needs. The gains from trade are pretty obvious here.

But sovereignty complicates things.

Countries don’t just want economic efficiency — they want to protect strategic industries for other policy objectives. For instance, the dairy industry, which is one of India’s largest employers, is politically protected from foreign products. Or, for that matter, Europe would want to protect its globally-competitive cars from foreign imports.

Most goods fall somewhere in between the sovereignty-complementarity spectrum. Here, countries may be willing to open up their markets, but only selectively and not immediately. The India-EU talks broke down because too many goods fell in the middle of the spectrum without much agreement.

India’s sovereignty

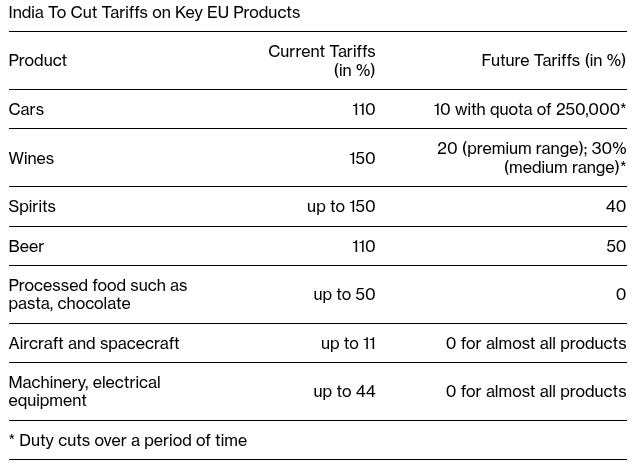

One of the biggest red lines was automobiles. European carmakers wanted access to India’s huge market, but we have been protecting our industry with high tariffs. In India’s view, opening the floodgates to brands like BMW and Volkswagen would hurt domestic auto investment.

Now, these are niche brands that operate in the luxury market. They are unlikely to threaten Indian cars, which are mostly built for the mass-market. However, India might still impose heavy duties for a few reasons.

One, it could incentivize those brands to invest in India to avoid those tariffs. Secondly, it could be protecting itself against future competition — if, for instance, Europe makes better EVs before us, then India’s own EV push would be undermined.

Another red line was agriculture. The EU wanted cuts on dairy, wine, and other farm products. but India wasn’t about to expose its 100 million small farmers to any European competition. This is despite the fact that Indian dairy is globally competitive and can hold its own against foreign products.

Europe’s sovereignty

On Europe’s side, the sticking point was always services. India wanted easier “Mode 4” visas for its IT workers, engineers, and consultants to work in Europe. However, immigration in the EU has been a touchy topic for a long time. It was politically explosive to give foreigners high-paying jobs — especially if there was high unemployment.

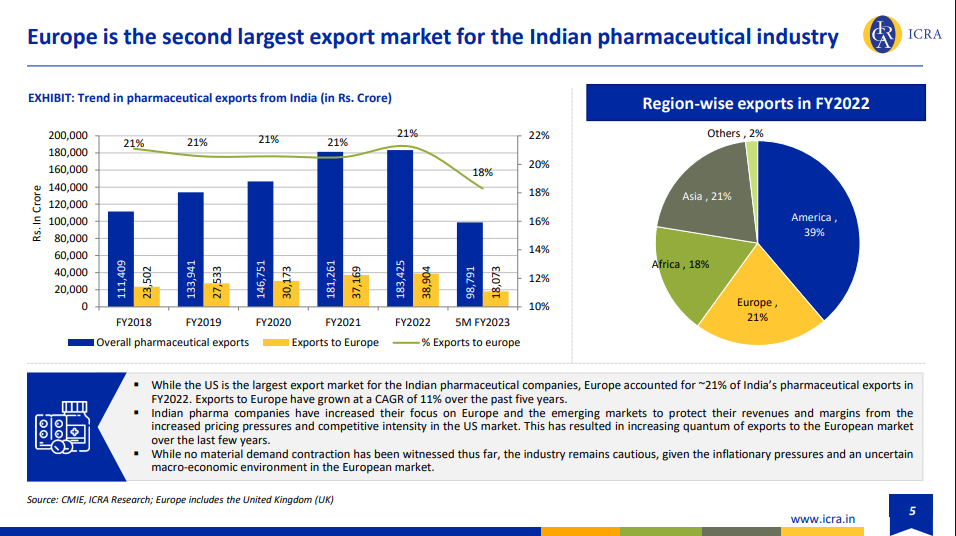

Pharma is yet another example. Europe is a drug innovator, holding many patents on new medicines. India, meanwhile, is the pharmacy of the world, exporting cheap generics made from expired patents — including to Europe, our second-largest export market. There is certainly a win-win here.

Yet, Europe has been pushing for a “data exclusivity” clause for its drugs. Under this clause, for a period, India could not rely on the originator’s clinical data to make their generics. This was a huge no-no for India, which saw this as a strengthening of monopoly power beyond the patent.

Neither here, nor there

Beyond this framework, there are also goods where, even when a clear win-win existed, trade barriers still existed.

See, for a long time, India was part of the special European list called the Generalized Scheme of Preferences (GSP). The GSP assured lower tariffs for imports from developing countries like ours. In particular, our textiles industry benefited heavily from this special status.

But, as India grew and its exports became more globally competitive, Europe didn’t see it fit anymore to include them in the GSP. So, our products were gradually phased out because we didn’t seem to need it anymore.

Yet, some of our peers that were phased out of the GSP, like Vietnam, had signed a trade deal with Europe. This led to lower European tariffs on Vietnamese products, effectively undercutting Indian goods. The best way out of this was to sign our own deal with Europe.

A necessary compromise

What accelerated the death of this stalemate seems to be geopolitics. The Ukraine war, for instance, fractured Europe’s energy security as they shunned Russian oil. China’s dominance grew more threatening. And Trump’s tariffs made the cost of not having alternatives painfully clear.

The most important question, then, is how did an India-EU deal succeed this time? In 2021, India and the EU decided to reopen the negotiation table, and agreed to fast-track the deal in 2023. The result of that is what we see today: not a resolution of every issue, but acceptable compromises.

We won’t be able to cover all the details of this deal. However, the easiest way to understand it is to use the same sovereignty-complementarity lens.

The easy wins

Let’s start with the goods where mutual gains were obvious and sovereignty didn’t matter much.

For India, this means labour-intensive exports — textiles, apparel, footwear — which is also the biggest chunk of India’s exports to Europe. The EU has agreed to eliminate tariffs (which ran as high as 12-17%) on these goods immediately upon the deal coming into force. More importantly, it levels the playing field with Vietnam and Bangladesh.

For Europe, the equivalent is capital-intensive machinery. India will slash tariffs on EU machinery from as high as 44% to zero over 5-10 years. Aircraft duties will also be eliminated. These are sectors where India isn’t trying to build domestic champions (yet) — we simply need the equipment to industrialise.

The hard bargains: high complementarity, high sovereignty

Then there are sectors where both sides can trade, but sovereignty concerns create friction. Both parties aren’t clear whether the gains from trade are substantial. Some of these required more creative solutions: where liberalization was either selective, or phased out slowly over time.

On services trade, the deal creates a framework for temporary entry of Indian professionals, like business visitors and intra-corporate transfers. It’s not the full “Mode 4“ liberalisation India once demanded, but it’s a step forward. Indian IT firms may find it easier to serve European clients on the ground.

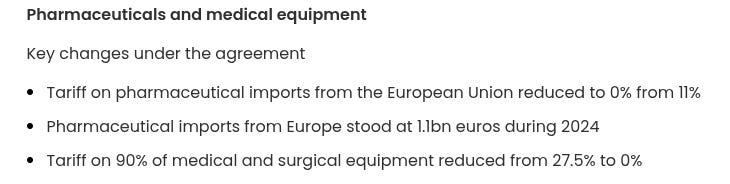

On pharma, India dropped tariffs on European pharma imports from 11% to zero, while the EU also reciprocated similarly. However, the EU’s data exclusivity clause was excluded.

There is one thing on which India had to almost wholly accept Europe’s terms: Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

CBAM basically functions as a tax on how much carbon an imported product has. This would force Indian firms (particularly in steel) to invest in capacity to green their exports, adding further to their costs. Despite plenty of lobbying, the EU didn’t offer any major exceptions to CBAM. But, it introduced a “Rebalancing Mechanism” in case CBAM reduced any other benefits from the deal that India is promised.

The toughest calls

Finally, there are sectors where sovereignty concerns outright dominate complementarity.

Automobiles were India’s biggest concession. After years of high tariffs, India has agreed to cut duties on most European cars to 30-35%, phasing down to 10% over several years. But the concession is carefully hedged — the 10% tariff only applies for luxury cars only, that too with a quota of up to 2.5 lakh units sold. Importantly, EVs are excluded from this benefit.

Agriculture, meanwhile, was largely kept out of the deal altogether. Tariffs on European wine and olive oil have been reduced. But as far as regular dairy and poultry go, India’s safeguards are just as tight as ever.

Conclusion

Perhaps, this deal is just the start of a stronger India-EU relationship. For one, they also signed a major defence agreement this week itself. They will also be deliberating on a separate investment agreement later. After 2 decades, both parties finally worked out a deal that didn’t sacrifice their sovereignty while finding win-wins that boost it even further.

But beyond that, what does it mean for global trade? In light of the global trade war started by the US and China, countries are trying to hedge against both. And one possible way to do so is by trading with each other.

That, perhaps, is what India — an economy that has historically shied away from being integrated into world trade — has been thinking. It’s why, as we wrote at the start of the year, we have been signing trade deals left and right. And the EU deal represents the high point of our hedging strategy.

India’s electronic future lies in its trash

We’ve spoken about this before, but it bears repeating: rare earths power the modern world. Inside many new technologies — smartphone speakers, EV motors, wind turbine generators, and more — sits a rare earth magnet.

These rare earths aren’t rare, exactly. But they’re hard to extract and make use of. They’re found dispersed, often amidst toxic or radioactive material, which makes them a nightmare to process. That difficulty can be an opportunity, if you’re willing to stomach the pain. That’s how a single country, China, came to control the entire world’s supply of rare earths. There are other places where one can find them, and all the necessary technology was developed in the West. Yet, China commands 70% of the world’s rare earth mining, and 90% of its refining capacity.

This dominance has come from its willingness to sustain brutal cost competition and bear tremendous environmental damage. As a reward, China enjoys a stranglehold on global technology. Every rare earth product in the world contains metal refined in China.

India’s trapped in that chokehold. We imported 53,000 tonnes of permanent magnets in 2024-25. 90% of those were sourced from China. We hold the world’s third-largest rare earth reserves. And yet, we produce just 2,900 tonnes of ore annually, which are exported to China for refining.

That dependency makes us deeply vulnerable, as we learnt recently. In April 2025, China restricted the export of several rare earths. Indian firms that depended on them were suddenly cut off. They had to now face a bureaucratic maze: applications were routed through multiple ministries, then verified by Chinese authorities. Of the 500-600 companies that applied for clearances, only a handful received approvals.

Entire industries stalled overnight, as we’ve mentioned before. Some were forced to redesign their products entirely, to work without rare earth components.

What options does India have, if this were to happen again? A recent paper by researchers at the Takshashila Institution argues for an interesting solution: urban mining.

The scope of our problem

The 2025 shock, sadly, is the mildest disruption India can expect, if China turns rare earths into a geopolitical weapon.

Our need for rare earths will only grow stronger than it was last year. The green transition alone will multiply demand several times over. Every electric four-wheeler contains roughly 1.5 kg of rare earth magnets. Modern wind turbines use up to 3 tonnes of magnets per megawatt. Meanwhile, as India grows more prosperous, we’ll buy an ever larger number of consumer durables — washing machines, air conditioners, and the like — which will add hundreds of tonnes to our rare earth needs.

We cannot mine enough rare earths to meet this wave of demand.

For one, our regulations can’t allow it. India’s primary rare earth reserves sit in monazite sands along the Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Odisha coasts. These deposits don’t just contain rare earths — they also have roughly 25% of the world’s thorium, a radioactive material. This brings those reserves under the jurisdiction of our atomic energy regulation, effectively locking out private miners.

This is unlikely to change soon. Even India’s much-touted 2025 reforms, which opened critical mineral mining to private players, specifically excluded atomic minerals.

This leaves India with a single major operator in the space — the state-owned Indian Rare Earths Limited. But its output barely even reaches one-twentieth of India’s demand.

Even absent these nuclear tangles, rare earth mining carries terrible environmental costs. To make a single tonne of rare earth oxide, you have to discard 2,000 tonnes of toxic chemicals. In China’s Inner Mongolia, for instance, there’s a lake of toxic black sludge that spans 10 square kilometers. This will have to be managed for generations. It isn’t clear if we want to, or even can, accept such costs.

But assume we did accept the costs. It would still take decades before we had an active rare earth mining ecosystem. China built its dominance over thirty years. India may not have that runway.

The case for urban mining

So what should India do? Takshashila’s researchers suggest urban mining — a hip name for recycling. This is what Japan did back in 2010, when China slammed it with a rare earth embargo. We should think hard about it as well.

The coming e-waste apocalypse

Before that, let’s talk about another looming crisis: toxic e-waste.

Every year, we generate almost 4 million tonnes of e-waste. This will only grow worse. As today’s electric vehicles and wind turbines reach the end of their lives, they’ll add millions of tonnes of e-waste a year. As will the new smartphones and appliances that Indians are purchasing today.

What will we do when the deluge arrives?

Right now, this waste is an environmental liability for us. But we can also look at it as high-grade ore: far better than anything available in nature. Natural rare earth deposits typically contain less than 5% rare earth oxides, by weight. The permanent magnets in e-waste, on the other hand, contain 25-30%. Today’s e-waste streams alone could yield ~1,300 tonnes of rare earth oxides a year — almost 8% of our needs.

By 2030-40, as today’s technology ages, that could rise to over 6,000 tonnes of rare earth oxides a year — enough to satisfy more than one-third of India’s demand.

That is, if we play our cards well. We need to anticipate and seize the coming moment. The infrastructure to capture and process this waste must be built before the waste arrives. If we wait until 2035, when waste volumes have already spiked, the opportunity will disappear.

What we need to do

We don’t already recover rare earths from our e-waste because it is hard.

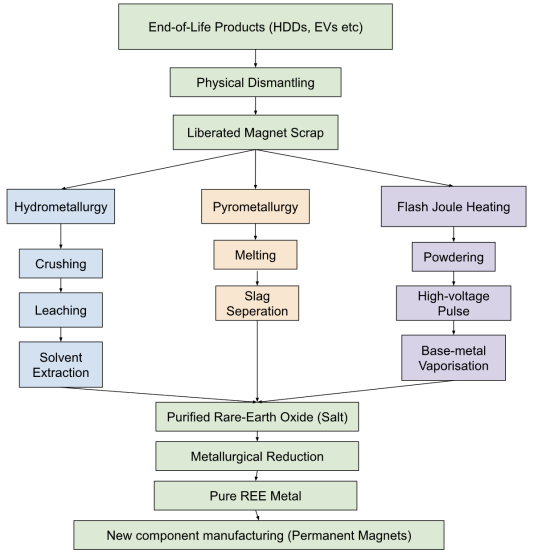

To make modern magnets, you need to mix them into other substances. Neodymium magnets, for instance, are often made by mixing the metal with iron and boron. To recover the Neodymium, we need to chemically break those finished magnets back into constituent elements.

There are three ways of doing so.

First, there’s hydrometallurgy — the most common technique, and the closest thing to processing ore. Here, we crush magnets into powder or granules, and treat the crushed material with strong acids that leach away the metals inside. From that dissolved metal, we then use special solvents to pull out the rare earths we need.

Hydrometallurgy is very effective, with recovery rates over 90%. But this also consumes lots of water and acid, and leaves us with a lot of hazardous, acidic liquid that we need to discard.

Then, there’s pyrometallurgy, which uses heat instead of acid. Here, magnet scrap is heated in furnaces or smelters. Different substances behave differently under the incredible heat, allowing us to separate them out. Unlike hydrometallurgy, this doesn’t create those liquid wastes. But it takes enormous amounts of energy, and is harder to control precisely. Without that control, it’s also less effective at separating rare earths out.

The most experimental of the three is flash joule heating. Here, we send extremely rapid electrical pulses through powdered scrap, heating it to temperatures hotter than the sun’s surface in milliseconds. This promises to be the cleanest of the three; reducing emissions by 84% and energy use by 90% compared to conventional methods, and eliminating acid waste streams completely. But it hasn’t really been tried at scale before.

None of these are cheap. The most common set-up — hydrometallurgical recycling — costs roughly ₹1,000 crores for meaningful capacity.

This isn’t where the story ends. These processes create an intermediate product: rare earth oxides or salts. These must be turned into usable metals in different industries. So, India needs to build a complete value chain downstream.

Why this is worth considering

In short, it is hard for India to set up an urban mining ecosystem. But it’s worth thinking of the benefits it can bring.

For one, rare earth recycling needs a highly trained workforce — chemical engineers to design and operate these processes, mechanical engineers to handle materials and maintain equipment, analytical chemists to maintain quality, and more. We already have a base of such workers within our industrial ecosystem. A thriving recycling industry could generate thousands of jobs directly, and more in supporting sectors.

We also have easy access to the feedstock this industry needs. Unlike primary mining, which requires finding and developing new mines, for urban mining, we simply need to tap into existing waste streams. We have millions of tonnes of e-waste that is currently being processed poorly, or not at all. If we can capture even a fraction of that, the volumes could seed an industry.

Finally, urban mining offers a double environmental advantage. For one, it avoids the catastrophic ecological footprint of primary rare earth mining. Additionally, it turns India’s e-waste crisis into an opportunity.

The bottlenecks

If this is so promising, why aren’t we doing it already?

Well, to realise this opportunity, we will have to build an entire ecosystem from scratch. Although India does process e-waste, it focuses on just four materials: gold, copper, aluminum, and iron. There are no regulatory incentives to recover rare earths.

Meanwhile, it’s extremely hard to reliably access e-waste. Most of India’s e-waste — 85-90% — flows through informal networks of kabadiwalas. They exclusively use crude, low-cost methods, to pry out materials with established scrap value. A kabadiwala dismantling a hard disk drive might pull out the aluminum platter and steel casing, discarding the magnets inside because they have no market price in the informal economy. This effectively destroys the feedstock before formal recyclers can access it. A recycling ecosystem, then, isn’t simply a matter of erecting factories, but of finding ways to integrate kabadiwalas into the formal system.

Besides, this is a market with brutal economics. After spending thousands of crores for a recycling plant, one will have to face extreme price volatility in the global rare earth market, because of China’s many moves. In 2011, for instance, Chinese export bans sent prices spiking as much as 1,000%, before they crashed abruptly. This makes planning impossible.

Meanwhile, our domestic market isn’t an option. India simply has no capacity to process separated rare earth oxides, and few industries use them.

There are some recent policy moves that try bridging this gap. For now, though, they’re insufficient. In 2025, for instance, the government created an incentive scheme for critical mineral recycling. But it was only allocated ₹1,500 crores, with a ₹50 crore cap per entity. Against ₹1,000+ crore capital requirements for a viable plant, this would be a mere drop in the bucket.

The proposal

To the researchers, if we’re serious about developing our own rare earth supply, we need a concerted policy push to fill major structural gaps.

For one, we need to improve supply. For that, we could change our current laws to incentivise rare earth recycling, possibly through “extended producer responsibility” credits. We could also import e-waste in a licensed manner, guaranteeing feedstock to the industry.

Two, we need to create guaranteed demand. For instance, the government can guarantee off-take for rare earths from domestic recyclers for a few years, effectively insuring them from the volatility of global markets before they mature. We can also do more to create a domestic magnet industry, creating natural buyers for this recycling ecosystem.

Finally, we can spur more investment, perhaps through a dedicated government entity.

For the details of their proposals, we recommend looking at the original paper.

Most importantly, the paper reframes our challenge in securing critical minerals. So far, we’ve thought of it as a question of “where can we mine rare earths”. The real question, instead, is “how can we find rare earths.” China’s monopoly on primary mining and processing may well be unbreakable. But that isn’t the only source that exists. The market for waste is still open. By tapping into it, we could kill many birds with the same stone.

Tidbits

The RBI and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) have signed an MoU allowing CCIL to reapply for EU recognition. This was after ESMA had earlier withdrawn recognition for six Indian clearing houses over supervisory disputes. The deal was signed during the India-EU summit.

Source: ETIndia’s industrial output hit an all-time high in December. The Index of Industrial Production reached a record 170.3, powered by manufacturing output growth of 8.1% and electricity production rebounding to an 18-month high of 6.3%. Consumer non-durables led the charge with 8.3% growth—the fastest since October 2023.

Source: BSPetrobras, Brazil’s state oil giant renewed and expanded contracts with IOC, BPCL, and HPCL for up to 60 million barrels through March 2027, as Indian refiners diversify crude supplies away from sanctioned Russian producers. India imports around 5 million barrels per day, making it a strategic market for Petrobras as it ramps up production from deepwater fields.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Strong take and I agree. This feels like a starting point, not the endgame.

India–EU is less about tariffs and more about strategic hedging in a fragmented trade world.

India’s shift - from cautious participant to selective integrator in global trade - is the real story here. Pharma, tech and consumer will move first; capital and supply chains will follow.

I’m reflecting more on these trade realignments and what they mean for leaders in The Marcus Brief.

If you look at media headlines and commentators on social media, all you see is hype about the EU-India FTA. However, this euphoria is misleading.

The evaluation of how “good” or “beneficial” an FTA (bilateral) needs to consider the following:

First, an FTA is essentially a “government-to-government” overarching framework in which to conduct a “business-to-business” activity. The actual operative entities on both sides are private parties making commercial decisions.

Second, all FTAs have what in investment theory is called “time to build”—the reduction in duties is phased out over long periods up to 10 years. So, nothing is going to happen tomorrow morning or even the day after tomorrow morning.

Third, a bilateral FTA does not imply that each party cannot be a party to other bilateral or multilateral FTAs. It is therefore important that an Indian exporter, for example, can quote a landed price that, with the reduced tariff, makes it competitive vis-à-vis other international producers. There are other subtleties, like “quality” [hedonic pricing] aspects, that might mean that the lower price may not always prevail – but let’s abstract from that for now.

The key issue, often forgotten, is that in FTAs the key players are private parties, not the government. To quote a competitive landed price, they need to be “efficient” producers in a sort of “globally competitive market” scenario. The landed price depends on firm-level efficiencies – input costs, labour costs, power costs, etc. The question is: Are these comparable with those of competing foreign producers? In a sense, an FTA is irrelevant; if you were a competitive producer, you would already be exporting with or without an FTA. The key issue lies in structural reform: domestic economic policies that encourage competition (even in the domestic market), allow firms to produce at lower costs, permit economies of scale, etc. Structural changes are a prerequisite. They don’t disappear when you sign an FTA. For example, the PLI scheme is a recognition of this – whether it will work remains to be seen.

Simply put, the question is: do you have a competitive price for a generic garment as compared to a Bangladeshi or Cambodian producer? Because the garment demand in the EU is not going to increase in the short run, you must compete for market share. For that, domestic productivity has to increase first; it’s the horse in the FTA cart.