Diwali, discounts and disposable income: The value retail story

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Value retail’s incredible quarter

DroneAcharya crashes into SEBI’s net

Value retail’s incredible quarter

India’s value retailers just closed one hell of a quarter, with a sudden industry-wide surge in business, which broke through years of muted demand. We began looking at this fascinating industry for our weekend show, Who Said What, because we found so much of what these companies said in their earnings calls fascinating. But that only pushed us to look deeper into the industry.

To understand this better, we’re looking at three companies — Vishal Mega Mart, V-Mart and V2 — for a window into what’s happening underneath the numbers. At their heart, all three have roughly the same promise: they’ll sell you decent-quality clothes and everyday goods, at a price that lower-middle class India is comfortable paying. Their trajectories, however, are very different. In a quarter like this, those differences become more visible than ever.

A word of caution before we begin. We’re soon going to do a lot of year-on-year comparisons, but those are all broken. There are nuances which make the last September quarter a bad baseline to understand this one.

The biggest of these was this year’s calendar. This year’s autumn festivities began earlier than usual. Most of the Durga Puja or Navrati period landed late in September, instead of mid-October, when it usually appears. People began their Chhath purchases early as well. For companies like V2 and Vishal Mega Mart, which boast heavy presences in East India, sales that would typically turn up in the December quarter were “pulled forward” into September.

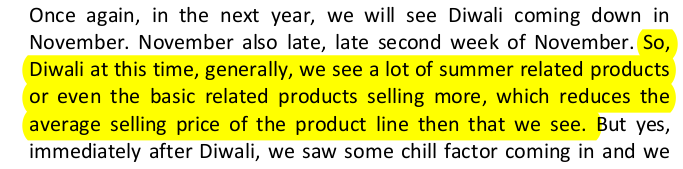

This affected their results — although it’s hard to understand by how much. The behaviour of a consumer can turn on a dime, creating weirdness that complicates the financial numbers of any consumer-facing business. V-Mart’s management, for instance, gave us an interesting example: since Diwali came earlier than usual this year, a lot of Diwali-shoppers bought light, summer-friendly clothes — instead of relatively expensive winter-wear pieces. Right as demand hit its peak, the company’s average selling price fell.

With that caveat in place, let’s dive in.

The scoreboard: three flavours of growth

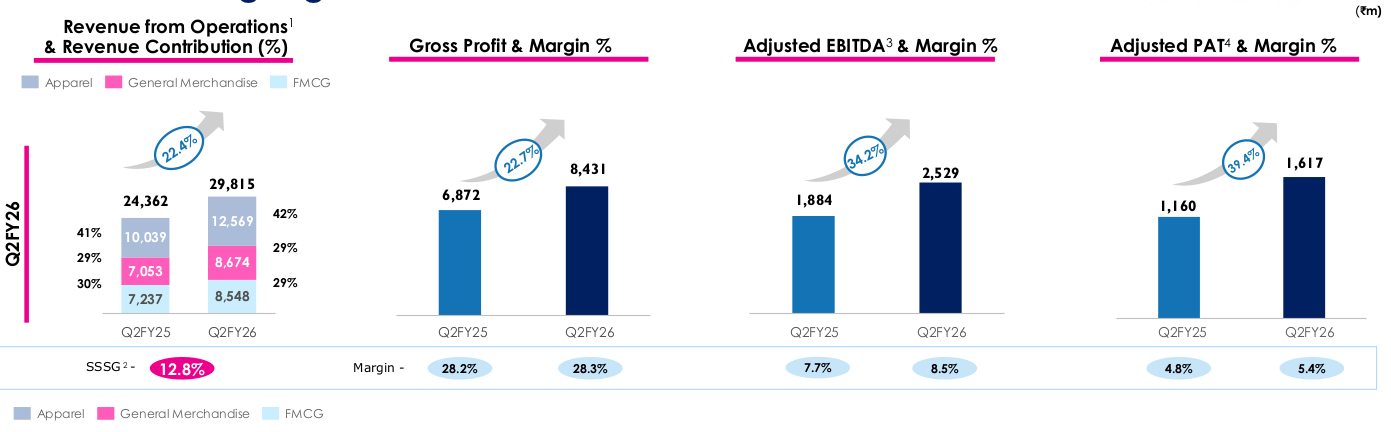

Vishal Mega Mart leads the pack, as a large, profitable retailer with a steadily compounding business. Last quarter, its revenues rose by ~22% year-on-year over an already high base, to come within touching distance of ₹3,000 crore. This remarkable growth was the outcome of two things put together — the company added nearly a hundred new stores over the year, even as each store grew its sales by an average of 12.8%.

Meanwhile, the company managed to crank more efficiency out of its business. Last quarter, its operating margins were the best of the three; comfortably above V-Mart and a shade higher than V2. Meanwhile, its after-tax profit margins grew to 5.4% — an enviable figure for a value retailer than sells cheap T-shirts and buckets.

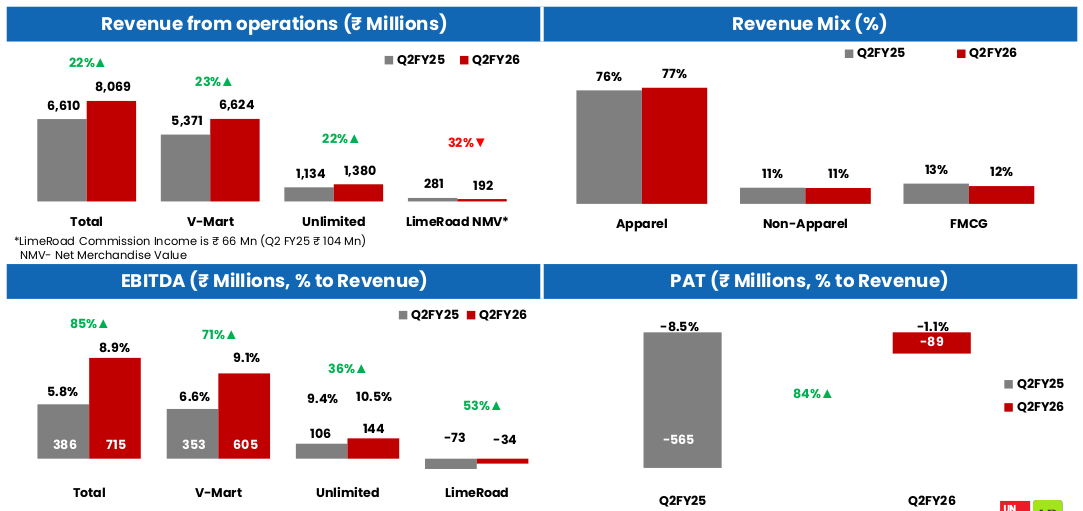

V-Mart’s business, in contrast, is in a very different place. It was bleeding cash until recently — but the company now seems poised to put that phase behind itself. Like Vishal Mega Mart, its revenues rose about 22% to a little over ₹800 crore in the quarter — again, a combination of its nearly 70 new stores, and a 11% spike in same-store sales.

Unlike Vishal Mega Mart, however, the company’s profitability is still fragile. On paper, it has EBITDA margins of 9% — which look robust. But that number looks a little too good because of the accounting standard Ind AS 116, which changes how your lease payments look in your financials. The company also reports its results with that stripped away, though, where its EBITDA margin drops to barely half a percent.

Altogether, the company made a small loss of ₹9 crore. To be fair, though, it made a much larger loss last year, so even this is good news.

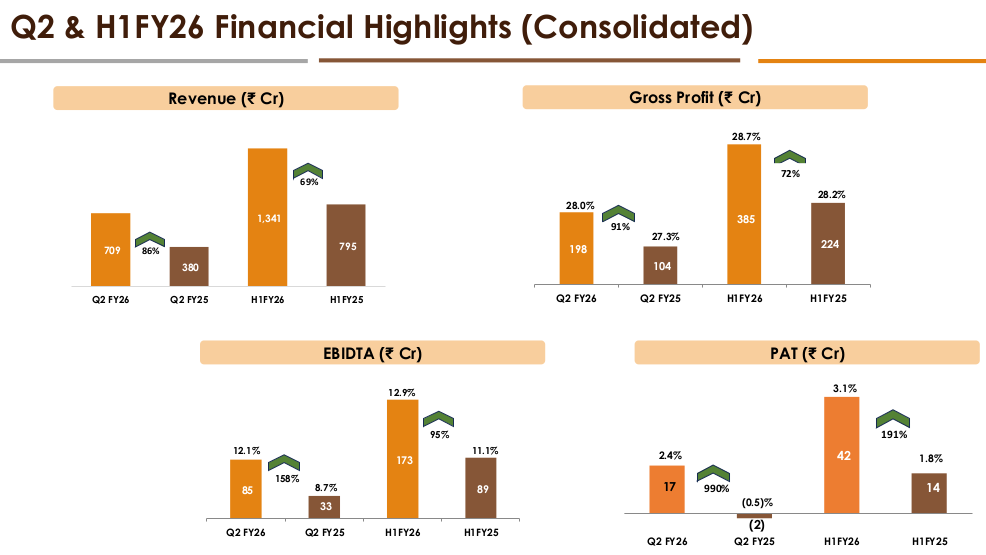

V2, meanwhile, had a blowout quarter. Its revenues almost doubled year-on-year, jumping up by about 86% to roughly ₹710 crore. Although it’s historically a much smaller business, last quarter, its sales were almost neck-to-neck with those of V-Mart. This isn’t all organic growth from the company’s old stores; the company’s same-store sales grew by a sober ~10%. Instead, that surge in growth came from how quickly the company opened new stores. In the last quarter, alone, it opened 43 new stores. That is, one in every six stores in the company’s network came from a single quarter.

Its margins, meanwhile, were healthy — at 12% (and ~6% with Ind AS 116 stripped away). This gave the company a comfortable after-tax profit of over ₹17 crore.

At a high level, Vishal Mega Mart emerges as the segment’s steadiest ship, with a healthy, growing business. Meanwhile, V-Mart is recovering from a bad phase, while V2 is scaling up rapidly to challenge the incumbents.

Understanding the value retail business

To us, though, there’s only so much that mere numbers tell you. More interestingly, the quarter-end communication from these companies teaches us how to think about a consumer-facing business in India, what choices they must make, and what customers are responding to.

The expansion imperative

Across the segment, all three companies have been scaling up rapidly. While all three saw their existing stores perform better than before, their incredible surge in growth came from how quickly they added to their existing networks. And this isn’t just a one-off thing; aggressive expansion lately seems like an industry-wide norm.

Is this strategy risky? Perhaps. But if V2 is to be believed, the economics simply make sense. Expansions appear to pay for themselves. Any new store they open, it appears, breaks even from the very first month. Against a breakeven point of ₹500 per square foot, the average new store begins with more than ₹750 in sales per square foot — and only grows from there.

With numbers like this, their business model lends itself to an aggressive roll-out.

Of course, that doesn’t mean you plop new stores anywhere. These companies all put tremendous thought into where those new stores open.

One of the big decisions a company must take, for instance, is whether to expand within a company’s existing catchment area, or whether to expand one’s catchment area altogether. V-Mart, for instance, is thinking about its expansion in terms of clusters. It’s opening new stores in clusters that it already has a presence in, and can support with its existing distribution network. V2, in contrast, is spreading its network out much wider — hunting for underserved markets, many if which in new geographies altogether.

But how you expand is equally a question of what your target region looks like. Take Vishal Mega Mart’s expansion into Kerala, for instance. As the company’s management noted, Kerala is almost continuously populated. The distinction between different cities is blurry — people live everywhere through the state. To reach such a population effectively, the company is thinking of creating a large network of small stores — so that its customers can access their nearest store more easily.

Understanding consumer behaviour

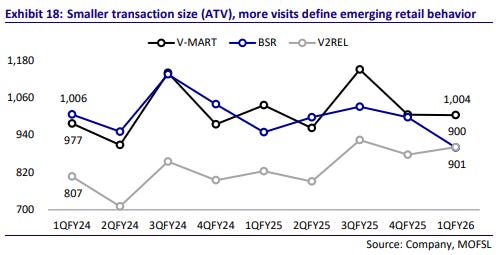

Value retail companies tell you about how a specific slice of India behaves. None of these are luxury chains which cater to those with large disposable incomes. Their customers are all extremely price sensitive — in fact, the average customer spends less than 1,000 per visit.

To look at their results, then, is to have a lens into the life of an average Indian consumer.

Their customers’ consumption is highly episodic — clustering around major festivals and weddings. That makes year-on-year comparisons extremely misleading, and easy to misinterpret. This is why, curiously, these companies are almost pleading with investors not to over-index on their exceptional quarterly numbers. V2, for instance, insists that you should ignore the quarter’s same store sales numbers, and look at their average growth figures over two quarters instead.

Here’s something curious, though: When customers do come to buy something, they aren’t always looking for cheap buys. Although they seek value, many remain fashion-conscious. And so, as this snippet from Vishal Mega Mart shows, companies in the value retail space are trying to do two things at the same time. On one hand, they’re trying to draw brand new customers, who are just entering the “consuming class”. At the same time, they’re also catering to customers who are upgrading to better clothing.

This gives the industry a curious dynamic: even though it’s catering to extremely price-conscious customers, this isn’t an entirely commoditised business. These companies aren’t simply fighting a price war, and their growth isn’t just a matter of suppressing margins. Instead, they’re looking for the right mix — one that delivers value, but protects margins at the same time.

How do you survive the new giants?

Zoom out of this quarter, and there are some looming existential questions that the industry must answer. This is a space that has the attention of giants, and competition is ramping up. Trent’s Zudio is making waves in the cheap fashion space. Reliance is making an aggressive entry with its own competing label, “Yousta”. Meanwhile, an online retailer like Meesho is selling T-shirts as cheap as ₹50–60 a piece.

This is no longer an industry where the first wave of organised players is eating into a hitherto unorganised market. It is one where entities with deep pockets are marching in.

This is a reality that these companies are alive to. All three companies have, in their earnings calls, mentioned the sheer intensity of competition they face. To some, this isn’t a big worry just yet — V-Mart, for instance, talks about there being enough space to accommodate these new entrants.

Even so, a moment like this has pushed these companies to think hard about how to maintain their position in an increasingly crowded market.

One lever they’re employing, naturally, is price. Companies are trying to keep their mark-ups as low as they can — especially for their entry-level products, which introduce customers to their brand.

But as we saw earlier, value retail isn’t purely commoditised. Rock-bottom entry prices, alone, can’t win you this business. And so, even as they fight a pricing battle, they’re simultaneously fighting to deliver better quality as well — by developing a suite of more aspirational products that are trendier and better in quality, that customers can graduate to.

The competition isn’t purely around customers, though. In an industry like this, it’s equally important to get the best vendors to work for you. These companies often purchase their stock from the same vendors as companies like Zudio. This makes it important to ensure that, for your vendors, your company is a priority.

Different companies are taking different approaches to this problem. For instance, V2 is trying to become the best paymaster in the industry — paying them early, even at the cost of stretching their own working capital. Financially, this is inconvenient for V2. But it makes them their vendors’ favourite customer, and even gets some suppliers to supply exclusively to them.

Finally, these companies are trying to improve distribution to beat out e-commerce oriented rivals. Vishal Mega Mart, for instance, has rolled out a quick commerce service from many of its stores — delivering to customers within a 8-10 kilometer radius from their store.

The bottomline

The value retail industry is endlessly fascinating to us — it’s touched by everything from weather, to festivals, to India’s consumer psyche. There were many tangents we couldn’t even get into — from the effect of the rains, to the GST cuts.

Perhaps the thing that interests us the most is the customer these companies serve. These companies serve those Indians that have just had their first taste of disposable income. These are people who can barely afford to part with more than a thousand Rupees on a shopping trip. But their choices are fascinating. Even at this low end of the market, they aren’t reaching for whatever is cheapest. They might hold off on purchases until a time like Diwali, but when they do spend, they’re looking for something nice to wear.

One thing is for certain: that customer base will only grow from here. The big question is, what market will new customers step into, when they first have money to spare. That, really, is what these companies are contesting for.

DroneAcharya crashes into SEBI’s net

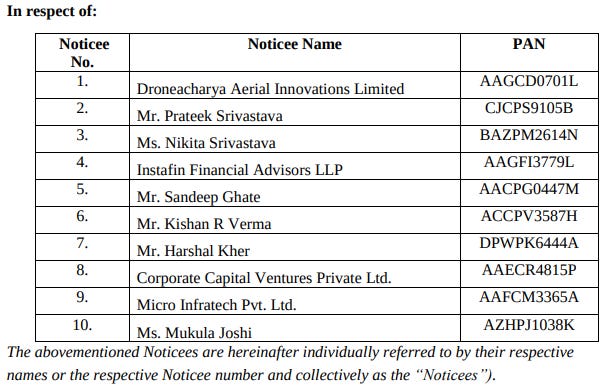

SEBI just passed an order against DroneAcharya Aerial Innovations Limited — a small, listed drone-training and drone-services company based in Pune.

On paper, DroneAcharya trains drone pilots and offers drone-related services. According to SEBI, though, there was something dishonest about how the company presented its business. It issued many announcements and financial statements that created an impression of growth that, SEBI says, did not exist. And worse still, it used investor money in ways it did not disclose.

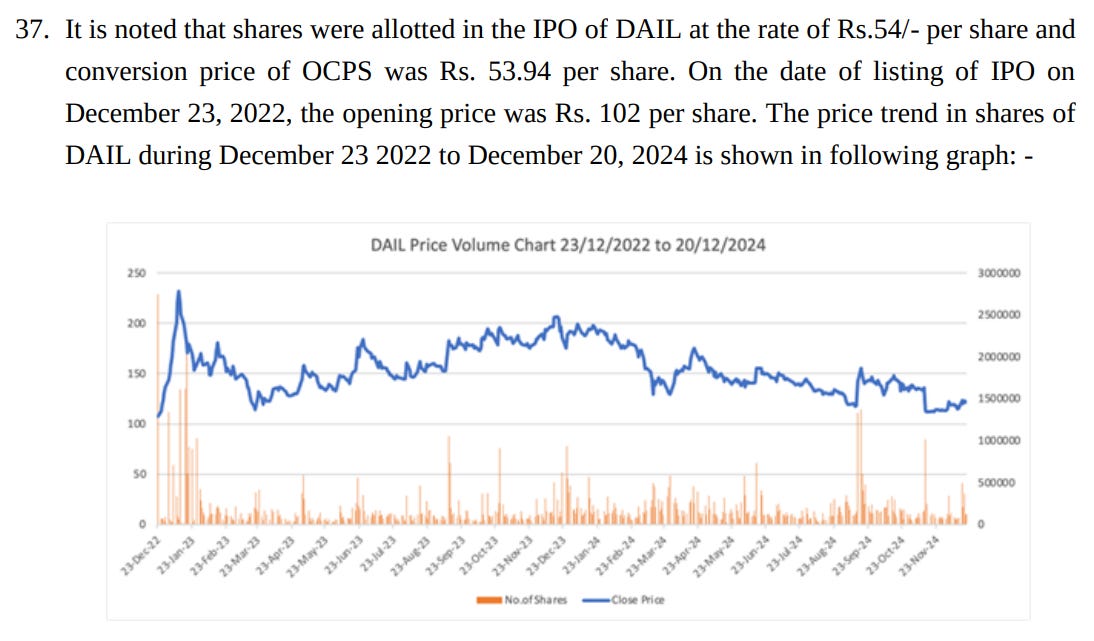

Not too long ago, DroneAcharya used to be a small company. It only got its DGCA approval in 2022. Back then, its revenues were modest, and operating cash flows were negative. There was nothing in the numbers to suggest that this was a business that would suddenly explode into multi-crore export orders within a couple of years. A year later, when the company made its IPO and got listed on BSE’s SME platform, it still didn’t seem like a sure-shot winner.

But soon, the company’s revenues started growing sharply. The company started releasing a continuous stream of announcements about orders, partnerships, and agreements that sounded substantial. This looked like an incredible success story in the making.

Only, there were patterns that did not add up. Even though the company’s revenues were sky-high, its operating cash flow remained negative. A large portion of the money it raised through its IPO seemed to have been spent, but not on the stated objects for which the IPO was raised. And all those announcements did not seem to translate into corresponding income.

These inconsistencies set off SEBI’s standard processes. The regulator sought bank statements, financial records, invoices, confirmations from supposed customers and vendors, minutes of meetings, board papers, and details of the IPO proceeds. Bit by bit, something dark emerged — somewhere, the company had pulled off a coordinated attempt to dupe the public.

The many lies of DroneAcharya

The first big problem had to do with the company’s shareholding.

Before the IPO, the company seemed to have given away shares to many people in private placements. It had also issued an unusually large number of bonus shares. At the time of its IPO, the company had amassed a base of 199 pre-IPO investors — some of whom were well-known market participants and film personalities. And the cost of each share was extremely low for these early investors.

Once the company listed itself, however, its shareholding pattern quickly changed. Its public shareholders grew rapidly, even as many of its pre-IPO investors reduced or exited their positions.

How did they manage that? Suddenly, that stream of announcements made sense. As the company announced big deals and headline revenue growth, its share price stayed elevated — even though there was little cash that seemed to enter the company. This allowed those early investors to sell their shares into a rising market, and exit the company with substantial gains.

To be clear, SEBI does not accuse these investors of wrongdoing. It doesn’t allege collusion, per se. SEBI’s point is not that issuing preference shares or bonuses is illegal. But it does hint at how convenient this all was. The perception of growth, achieved through false means, is what allowed them to sell at significant gains.

To add to this, there was a second problem. The company had been up to weird transactions before its IPO.

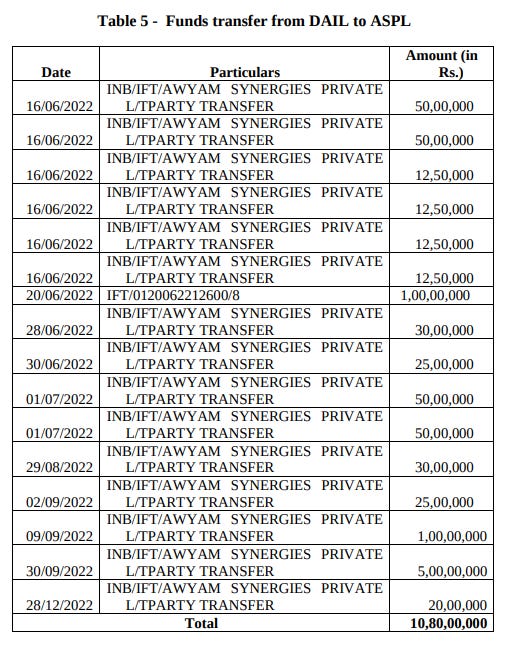

It had sent a significant chunk of money — ₹10.6 crore — to Awyam Synergies Private Limited (ASPL), a company that was entirely owned by DroneAcharya’s own promoters, Prateek and Nikita Srivastava. That clearly made ASPL a “related party” to the company. Under the law, you need to clearly disclose any transactions you’re entering into with a related party, especially when you’re going public. Only, there was no mention of that in its prospectus. And this entire set of movements was concealed from the public as well as from the company’s own audit committee.

Even after the IPO, the company sent an extra ₹20 lakh to ASPL, when the company had public money in its accounts.

That brings us to the third problem. Once the company had raised funds through the IPO, it used that money for all sorts of things — little of which was disclosed to investors.

See, when companies raise money through an IPO, they can’t use it for whatever they like. They have to clearly specify what they need money for, and then, they need to stick to those ends. When DroneAcharya went public, its IPO documents stated that most of the money raised — over ₹28 crore — would be used to purchase drones and accessories from four listed vendors.

Only, when SEBI actually looked, it found that a very small amount was spent on drones.

So where did the rest of the money go?

SEBI found that the company had funnelled large sums into all sorts of purchases, which it had never talked about in its offer documents — laptops, assembled desktops, refurbished computers, even 3D printers — all booked under the broad label of “drone accessories.” It also spent ₹12.45 crore on vendors who were never mentioned to investors. Some of that money simply became the company’s working capital — again, without shareholder approval or proper disclosure.

In short, the company completely failed to maintain any transparency; and almost everything that was meant to be pre-approved was improvised. Worse still, when SEBI reviewed the invoices and contracts used to justify the use of funds with other vendors — such as Micro Infratech and Data Setu — it found that many were either fictitious, inflated, or poorly supported by any underlying documentation. Together with the undisclosed advances to the promoter-owned ASPL, they painted the picture of a company moving large sums of money around on the basis of paperwork that simply didn’t hold up to scrutiny.

The biggest lie: Inflated revenue

The heaviest part of SEBI’s order deals with revenue recognition.

DroneAcharya reported a jump in revenue from ₹3.6 crore in FY22 to over ₹35 crore in FY24. A large portion of that revenue came from two foreign entities: Triconix Industrial Solutions, based in Qatar, and IRed, based in the UK. For a small training-focused company that had only recently received DGCA approval, such a sudden concentration of high-value export sales was unusual. This was either an incredible business that genuinely broke into a new market very quickly, or the numbers would deserve closer attention.

And so, SEBI wrote to these entities to verify the transactions. Their responses did not match what DroneAcharya had recorded in its books. Triconix stated that it had not received goods or services corresponding to the large export order that DroneAcharya had announced. On deeper inspection, SEBI found that quotations, purchase orders, delivery orders, and invoices had all been created on the same day — something that simply did not resemble the natural flow of a commercial sale.

Here’s one instance: at one point, the company announced that it had secured a $1.26 million order from Triconix. But at the time the announcement was made, only a quotation had been sent, and the acceptance email from Triconix came hours after the announcement. Meanwhile, a key foreign remittance was rejected by HDFC Bank, meaning the company had booked revenue for which no money could have come in.

In the case of IRed as well, SEBI noted delays, missing proofs of delivery, and lack of evidence that the services or goods corresponding to the claimed revenue had been provided.

These two customers, together, represented most of the company’s reported “exports”. SEBI concluded that DroneAcharya had recognized revenue without completing performance obligations, and in some cases without performing the underlying work at all.

How corporate announcements shaped perception

Those exports, however, weren’t the only announcements the company had made. In fact, after listing, DroneAcharya issued a stream of corporate announcements — some about franchise expansions, others were about university tie-ups, several regarding orders from defense-related or security-related entities.

SEBI examined 34 such announcements. In 20 of them, it found that no actual business followed. They were statements of intent, MoUs, or preliminary discussions — but no updates were given out when they resulted in nothing. In the remaining set where some work happened, the amounts were small — sometimes as little as ₹26,000 or ₹1 lakh. To SEBI, these announcements were drafted in a way that gave investors an impression of significant growth and operational expansion, even though the underlying business remained limited.

One announcement said that the company had “secured” India’s largest FPV drone export order worth ₹15 crore from a firm called MBD. Only, SEBI found that this “customer” was effectively a one-man company — and that the foreign remittance attempts associated with the supposed export were rejected. The company never disclosed that the order had collapsed.

SEBI also reviewed announcements around “Make in India” manufacturing partnerships with foreign entities. In several cases, DroneAcharya was primarily importing and reselling products while presenting the arrangements as domestic manufacturing initiatives.

The regulator’s concern was not that the announcements were optimistic. It was that taken together, they created an impression of scale and momentum that was not supported by the company’s financial reality.

What SEBI has ordered

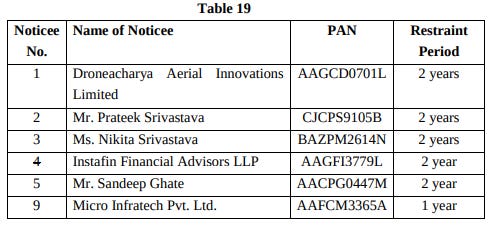

SEBI has restrained DroneAcharya, its promoter-directors Prateek and Nikita Srivastava, and a series of other entities from accessing the securities market. The bans range from one year (in Micro Infratech’s case) to two years for the others. They are also prohibited from buying or selling securities, except to close out existing positions under specific conditions.

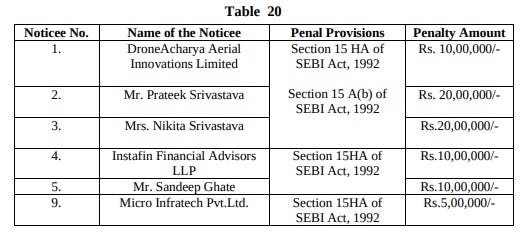

The regulator has also given out a series of other penalties — totalling to ₹75 lakh.

The penalties are meant to reinforce a simple fact: in small-cap and SME markets, in particular, it’s almost too easy for companies to shape perceptions, as scrutiny is thin and disclosures go unquestioned. If too many companies abuse this fact, it could well undermine the fragile trust under which public markets run. Investors don’t just buy into businesses; they buy into our stock market as a system. Cases like this show how quickly that faith can fray.

Tidbits

India’s electric two-wheeler registrations fell 21% to 110,761 units in November. Moreover, formerly a leading brand, Ola Electric has dropped to fifth place (8,254 units) — as Hero MotoCorp’s Vida brand overtook it with 11,795 registrations.

Source: BS

The government just approved a ₹305 crore Tex-RAMPS scheme — a fully funded initiative running from 2025 to 2031, to strengthen research, data systems, and innovation in India’s textiles sector.

Source: TOI

India’s manufacturing PMI fell to 56.6 in November from 59.2 in October, a nine-month low, as US tariffs pressured export orders and business confidence dropped to its weakest level in three-and-a-half years.

Source : BS

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Have you guys done a deep dive into Meesho yet? Will be interesting to read given the presence in value retail and their unique no-commission model. If you do end up covering it, recommend looking in depth at their ads business (the model, current traction etc.). My understanding is that's the most important piece of their monetization strategy, and despite that coverage in media and even the IPO collaterals has been negligible.