Diagnosing the Diagnostic Business

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Diagnosing the Diagnostic Business

Does nobody like fast food anymore?

Diagnosing the Diagnostic Business

When people in investing circles talk about healthcare, the conversation almost always gravitates to two giant segments: pharma services and hospitals. It makes sense too; the two swallow the bulk of India’s medical spending. But there’s a third space — smaller, and far less glamorous — but one that sits at the heart of the entire system: diagnostics.

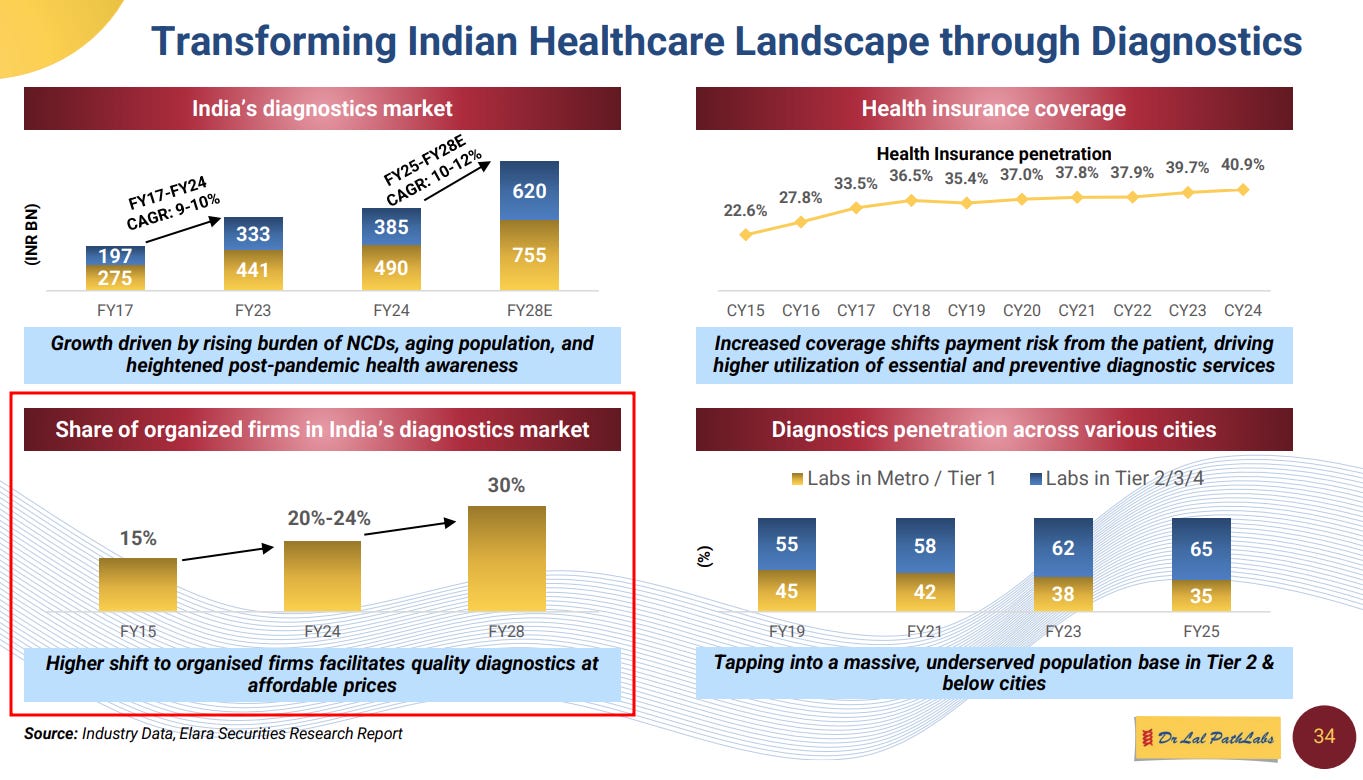

Diagnostics makes up less than 10% of India’s total healthcare spending. That’s tiny on paper. At the same time, though, diagnostics has been one of the most lucrative wealth-creation stories in Indian healthcare. Companies from the sector — like Dr. Lal PathLabs, Metropolis, and Vijaya Diagnostic — have built businesses worth tens of thousands of crores. The industry’s EBITDA margins have hovered around 25–27%, which is unheard of in most of healthcare. And the industry is growing steadily. CareEdge pegs diagnostics at a ~12% CAGR, heading toward a $15–16 billion market over the next few years.

To us, this made the diagnostics business an interesting rabbit hole to go down and learn about from the ground up.

What does a diagnostic company do?

The core business

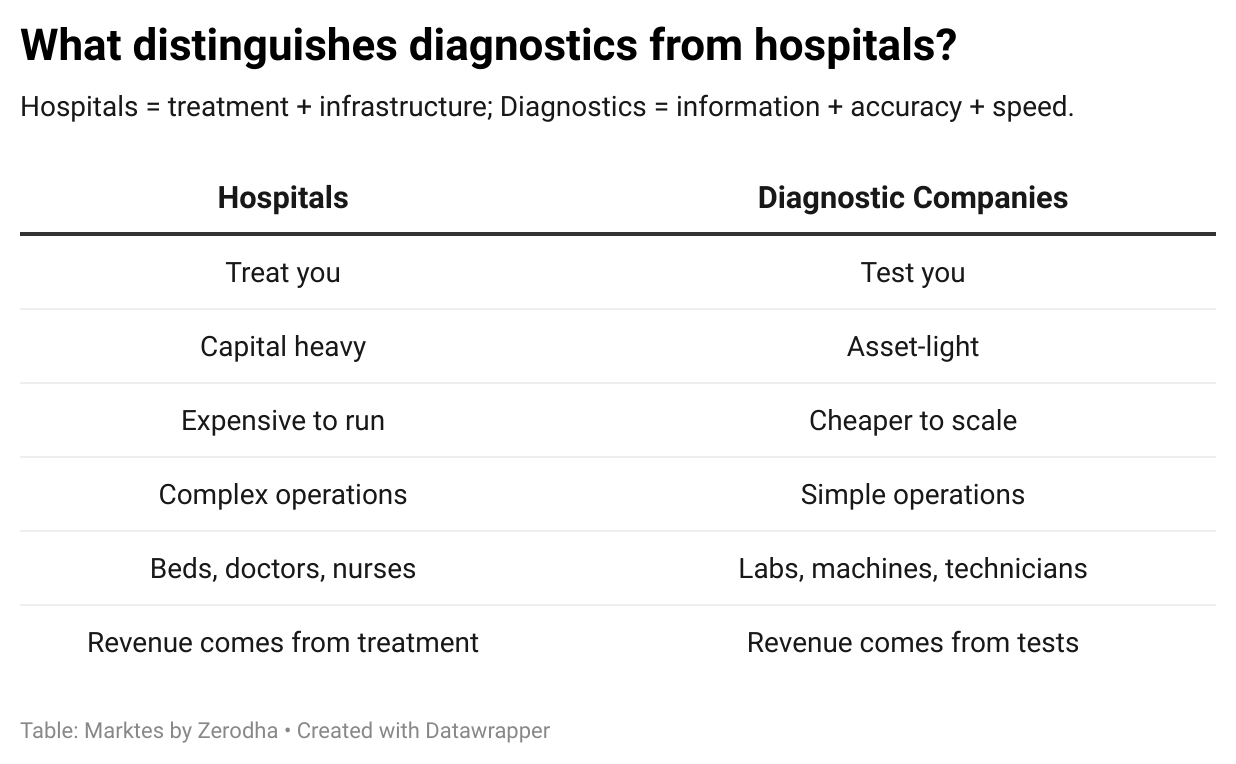

People often lump diagnostics into the same bucket as hospitals — but the two businesses couldn’t be more different. A diagnostic company doesn’t treat you. It doesn’t operate ICUs, admit patients, or perform surgeries. It has a single focus: running tests. Diagnostics companies trade in information.

Industry players divide the types of tests they run into three buckets:

First, pathology. These are tests on blood, urine, tissues — your regular CBC, blood sugar, vitamin levels, and the like. These everyday use cases are the industry’s “bread-and-butter”, and it’s where they get the most volumes.

Second, radiology & imaging — which includes X-rays, ultrasounds, CT scans, and MRIs. This isn’t a high-value business, either. Vijaya Diagnostics focuses heavily on this market, building a deep imaging-heavy model unlike its pathology-focused peers.

Third, advanced and specialized testing. This is the high-skill, high-margin end of the industry — with a focus on genetics, cancer markers, molecular diagnostics, hormonal tests, and more. CareEdge noted that genomic testing, in particular, is now one of the fastest-growing areas in diagnostics, consistently clocking double-digit growth and offering superior profitability. It requires very specialized machines and brings small volumes, but the margins are incredible. Dr. Lal and Metropolis keep highlighting this segment in their earnings.

De-coding the business model

Financially, diagnostics companies work very differently from hospitals.

Hospitals are capital-heavy. A hospital needs land, buildings, ICUs, operation theatres, and expensive equipment. All of this requires massive upfront capex, which only pays back over long periods. They pay for expensive round-the-clock staff. Hospitals also have a longer receivables cycle — they have to deal with Third-Party Administrator (TPAs) for insurance claims, and so, money doesn’t come to the bank as soon as they give their services.

Diagnostics, on the other hand, doesn’t suffer from any of that. They’re usually asset-light businesses. A diagnostics lab only spends on testing machines and solid IT systems, and runs their business by paying phlebotomists and a network of tiny collection centers, often franchised. That’s why diagnostics enjoy high asset turnover — they’re able to generate more sales on a smaller asset base.

They’re also paid immediately, which makes their working capital a lot more manageable.

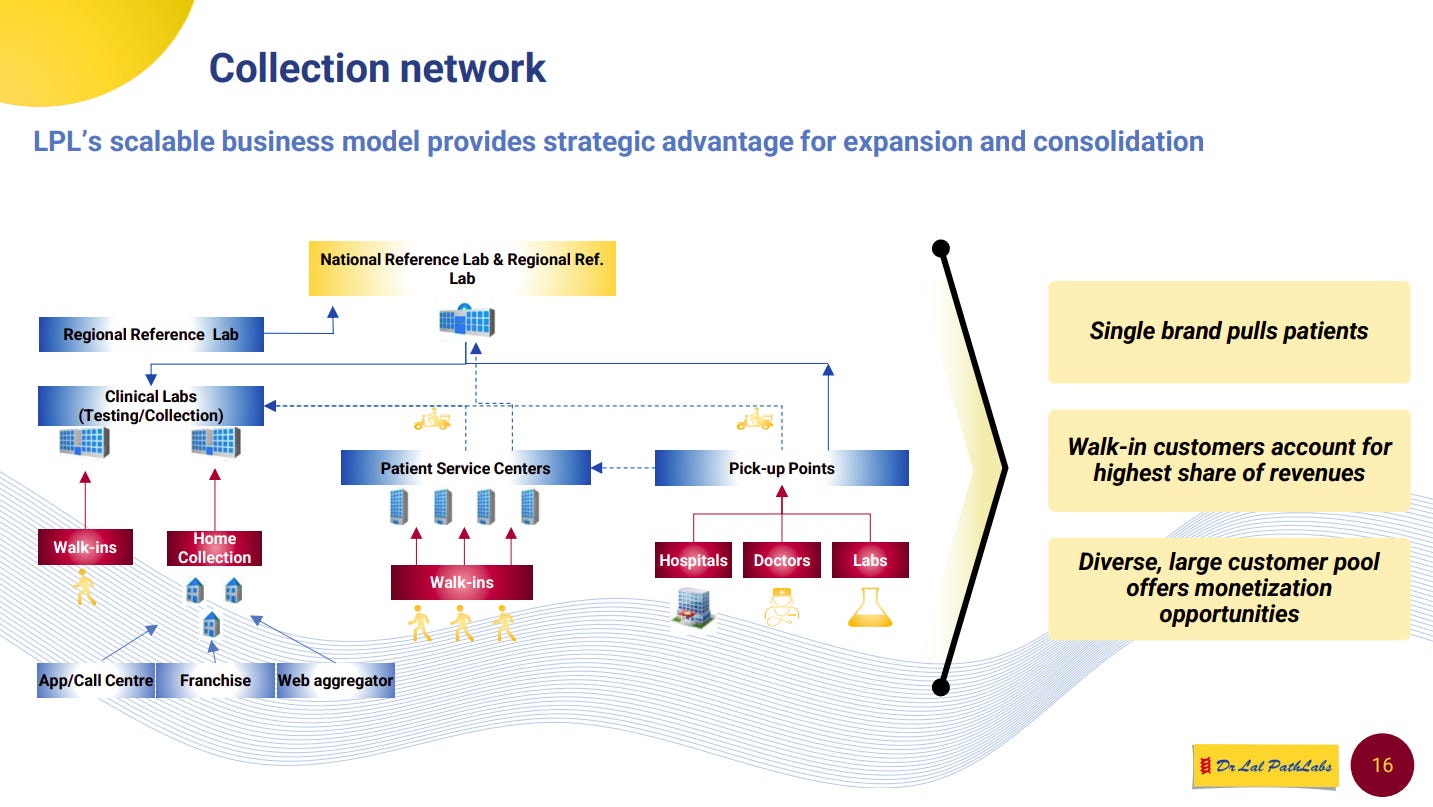

Weirdly, the business of diagnostics runs more like a logistics company than a healthcare company. You collect samples across a city — or even several cities — move them quickly and safely to a central lab, and then process them at scale. To pull this off, they rely on something that’s all too common in logistics: a “hub-and-spoke model”.

They don’t replicate labs everywhere. They simply set up “spokes” — tiny collection centres and pick-up points, or even collect samples from home. These take little capex and small staff sizes. Their role is simple: collect as many samples as possible and quickly send them for processing. Often, diagnostics companies don’t spend on these at all; instead franchising them.

Once collected, samples are sent to a central hub — the main processing lab where most tests are actually performed. This is where most of their money is spent; as they maintain high automation, expensive machines, and highly trained pathologists. The rest can be set up cheaply. This makes diagnostics a business that can scale up quickly.

Dr. Lal PathLabs, for example, has just 298 labs, connected to a network of 6,607 patient service centers and 12,000+ pick-up points. That’s how they reach 29 million patients a year without building huge facilities everywhere.

How do diagnostic companies make money?

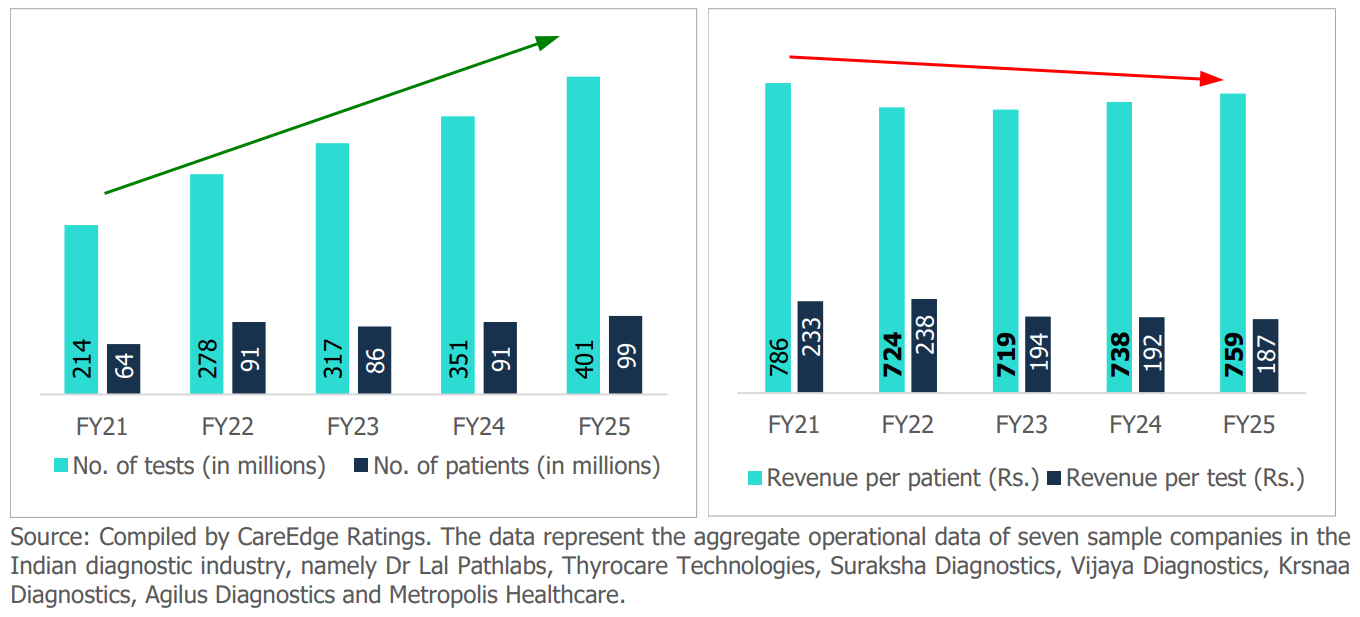

This is a business with interesting economics. Its revenue usually comes from volumes, not pricing. And it’s going further down this direction; unlike other businesses, where companies slowly ramp up prices to shore up earnings, in diagnostics, the opposite is happening. This is clear from CareEdge’s data; in the five years between FY 2021 and FY 2025, revenue per patient fell — from ₹786 to ₹759. Revenue per test fell even more drastically in the same period; from ₹233 to ₹187.

Instead, these companies are growing by carrying out an increasing number of tests on more and more patients. Even as prices fell between FY 2021 and FY 2025, the industry saw 12% CAGR in patient volumes and a 17% CAGR in the number of tests.

This dynamic makes a lot of sense — because the marginal cost of new tests keeps falling as volumes go up. Once you’ve set up a lab, the machines sit there. Your technicians are already staffed; your backend is already running. It costs almost nothing to run one extra test. Any additional revenue flows straight to your bottomline. The more samples you funnel into a setup, the more profitable the business becomes. That’s why these companies try to acquire as many customers as possible.

They do that in two ways: B2C vs B2B.

B2C — where customers walk in, or book a home collection through an app — is the high-margin, low-volume side of the business. This is the sweet spot; customers pay retail rates, bringing better realizations. Moreover, if a person directly opts for a test from a brand, that makes them more likely to remember the brand, which means they might come again for their next test. Dr. Lal, for instance, gets ~74% of revenue from B2C — which is perhaps what makes them the largest and most profitable chain in India.

The alternative is B2B, where diagnostics companies act as suppliers to hospitals or large clinics, which send them bulk samples at a discounted rate. The volumes can be huge with such a business, but margins are much thinner than B2C.

At its core, diagnostics is a cost game

The tests a diagnostics lab carries out, in some sense, are commodities. Two labs that carry out the same test, at least if they’re accurate and punctual, are virtually identical. And so, most consumers won’t pay a premium. This keeps prices flat, or even declining.

And so, the only way to make money is to drive down cost per test, drive up volumes, and build trust, so customers keep coming back

This bakes in an innate advantage for large, organised chains. They can keep costs low by buying reagents — chemicals used in diagnosis — in bulk, automating more processes, and running larger labs that have high utilization, while offering consistent quality. Small labs simply can’t compete at the same cost.

That’s why the diagnostics is simultaneously consolidating and getting more competitive at the same time. In this business, large players keep getting larger, but that doesn’t create room to charge a premium — because they’re in a fierce, unending competition with other large players.

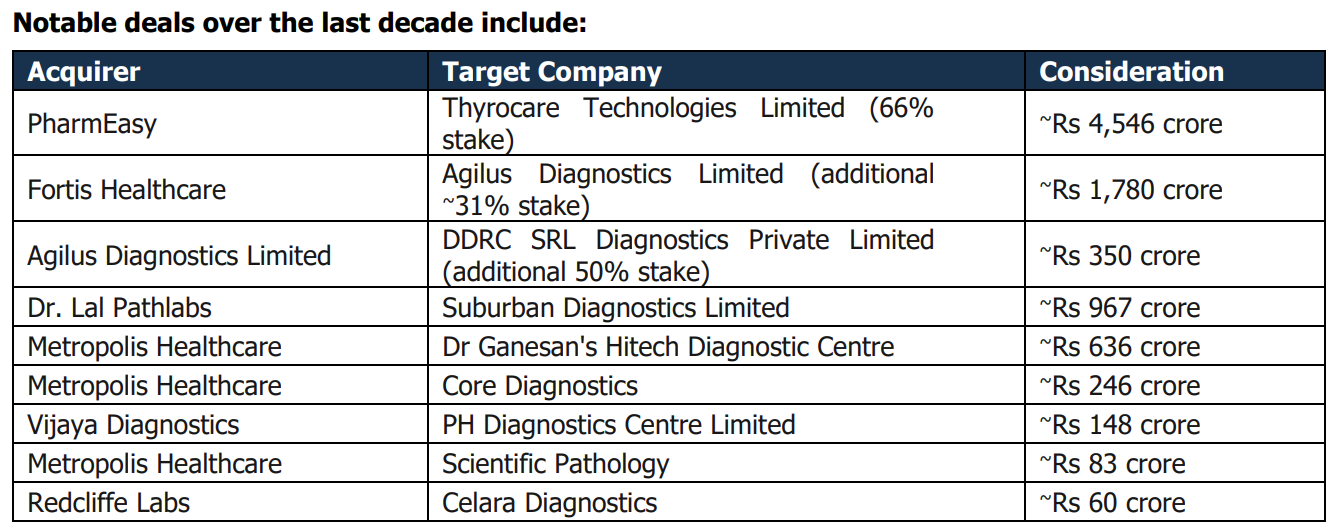

Meanwhile, other parts of the healthcare system — like hospital chains (Apollo, Fortis), Pharmaceutical companies, and e-pharmacy platforms (1mg, PharmEasy) are all trying to get a piece of this industry, because it suits their adjacencies. They already have customers, logistics, or capital. The money-spinning diagnostics game feels like a natural extension. Their entry, too, has led to price wars, discounts on test package,s and higher customer churn.

Where the industry is headed

We won’t go into the industry’s quarterly numbers this time around. But we came across two key themes in the industry’s quarterly concalls, which point to where the diagnostics business is heading next:

One, most companies have an eye on GLP-1, the miracle weight loss drug. GLP-1 therapies require constant monitoring, because of the sheer number of bodily systems it interacts with. That makes it a potential long-term tailwind. So far, however, most companies are cautious — and are still thinking of how to devise a bundle that works. It isn’t a revenue line yet. But it could, in the future, become a massive market.

[We first identified this trend during the research of another newsletter we run called “The Chatter” where we go through concalls of all companies we find interesting. Check it out for hidden insights from management commentary.]

Two, most companies are doubling down on advanced and genetic testing. While across the industry, test prices are falling, this segment still offers high margins. And so, companies are investing in oncology, genomics, or high-end imaging. Expect this to be where the next leg of growth comes from.

Fundamentally, the pricing of basic tests isn’t going up. And so, the industry is trying to evolve a higher-end, tech-enabled health-intel business.

Does nobody like fast food anymore?

The QSR sector hasn’t been doing too well, and for a while at that. That didn’t change this quarter either.

To understand this better, we’re looking at the results of three major QSR companies: Jubilant FoodWorks, which runs Domino’s, Westlife Foodworld, which runs McDonald’s, and Devyani International, which operates KFC and Pizza Hut.

Collectively, they tell a familiar story: Jubilant was the sole bright spot; it’s the only one that seems to know how to grow in today’s conditions. Westlife had built expectations up for months, but those fell apart this quarter. Devyani struggled as well; despite having multiple restaurant brands, it can’t seem to get customers to open their wallets.

Together, these three results draw a nuanced but concerning picture of where India’s fast food market stands.

The Domino’s aren’t falling yet

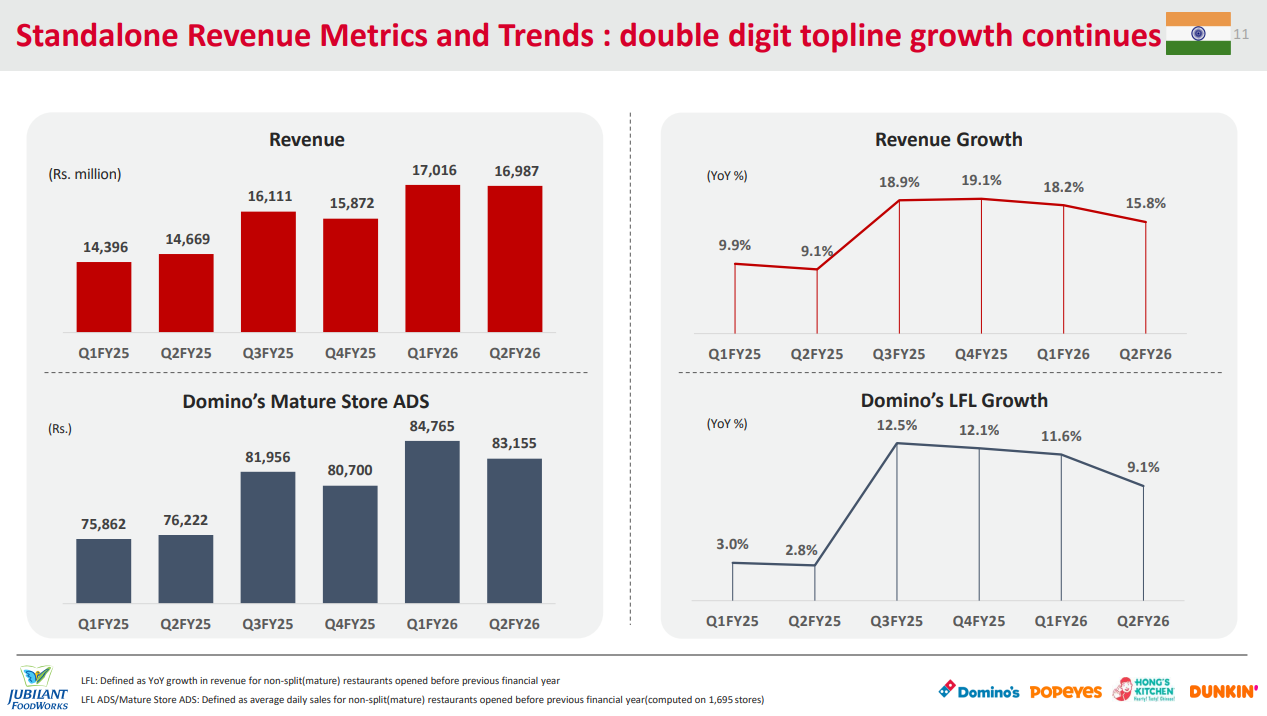

At a time when Domino’s is reeling from flat sales and closing stores across the world, its Indian arm is extending its remarkable run.

The company’s revenue, at a group level, grew by 20% year-on-year in the quarter gone by. Its revenue from Domino’s India, specifically, grew by 15.8% year-on-year. And crucially, its “like-for-like” growth — or the increase in sales it made from the same stores as last year — came in at 9.1%. That’s its seventh straight positive print.

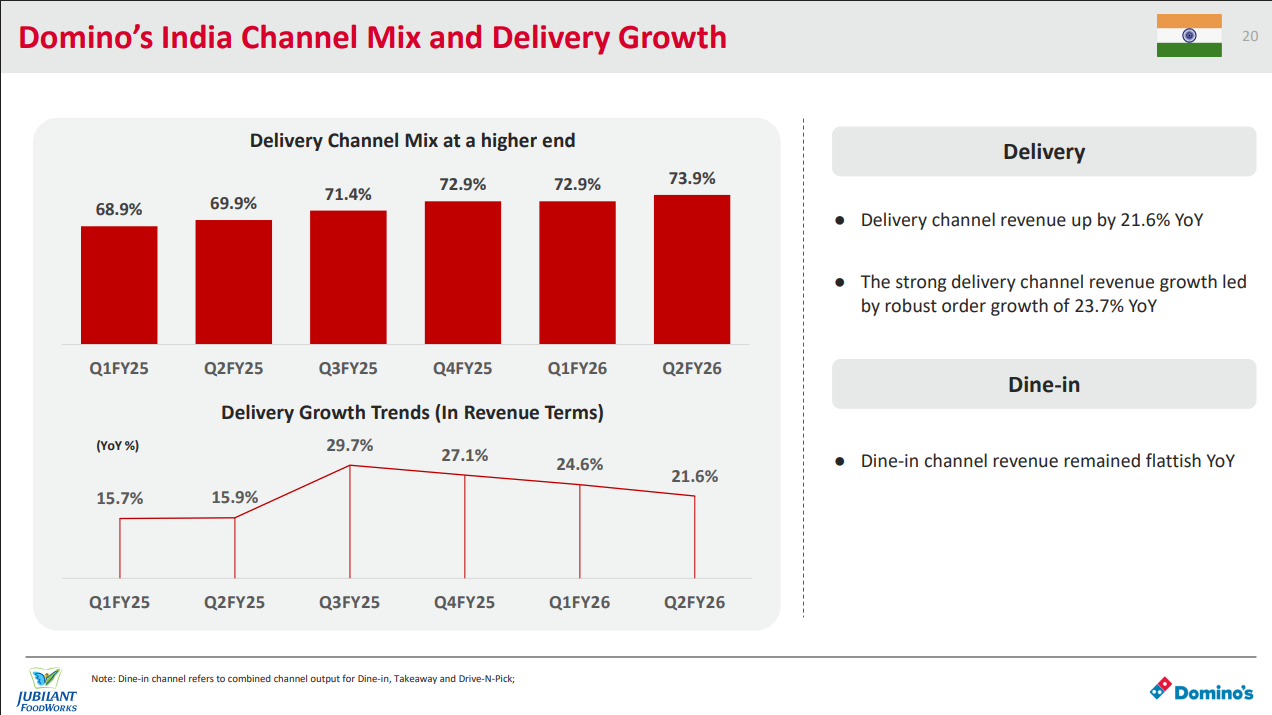

Behind these remarkable figures is a single engine: pizza delivery. Domino’s stores, themselves, aren’t attracting more diners. Delivery, though, is another story — approximately one year ago, the company decided to make delivery free, to fend off the constant encroachment from food delivery apps on its turf. It was an expensive decision, which would hurt margins. But by all accounts, the decision paid off. Ever since, its revenues from delivery have grown by more than 20% year-on-year.

As Sameer Khetarpal, the CEO, put it, “Delivery channel revenue growth continues to be over 20%, demonstrating the lasting effectiveness of our free delivery initiative”

That delivery business, however, has been eating into another channel — takeaway. Previously, many Domino’s customers would go to stores to pick up orders and carry them home, because doing so was cheaper. Once delivery became free, that stopped making sense.

But really, there’s no single approach that works everywhere. For instance, Domino’s is deliberately growing into small-town India. This quarter, it added 81 new Domino’s stores in places like Siwan, Dhubri, and Amroha.

These are markets where recognised fast food brands are largely absent, but people want such brands. For them, Domino’s entry was a big deal. In these parts of the country, the demand for ordering in is muted; people still like going out. And so, the company’s been opening far larger stores that can accommodate a lot of dine-in customers.

Meanwhile, the company has been tinkering with its offerings and the price it can get for them.

For instance, it recently launched something called its “Big Big Pizza” — large pizzas meant specifically for groups, where you get various flavours within the same box. It recently ramped up the price of these to defend its margins.

But then, it abruptly reversed this change. As the company explains, once the GST on cheese was cut from 12% to 5%, the company found more breathing room. And it clearly felt the need to immediately pass those cuts on to customers.

At the same time, however, with other products, it has ridden the premiumisation wave visible in so many consumer-facing industries. Take its new launch of sourdough pizzas — which cater to a more premium audience and come with better margins. To the company’s surprise, these were a big hit in tier-2 and tier-3 cities, where one wouldn’t expect gourmet products to work.

According to the company’s management, experiments like this might open the door to a different approach —- it might chase margins rather than volumes.

Perhaps it’s because this clear path has opened that, after months of refusing to give any guidance, the company finally set out a clear model: Domino’s India should grow about 15% a year, with 5–7% coming from like-for-like. That’s a major shift in its tone.

Of burgers and Bengaluru

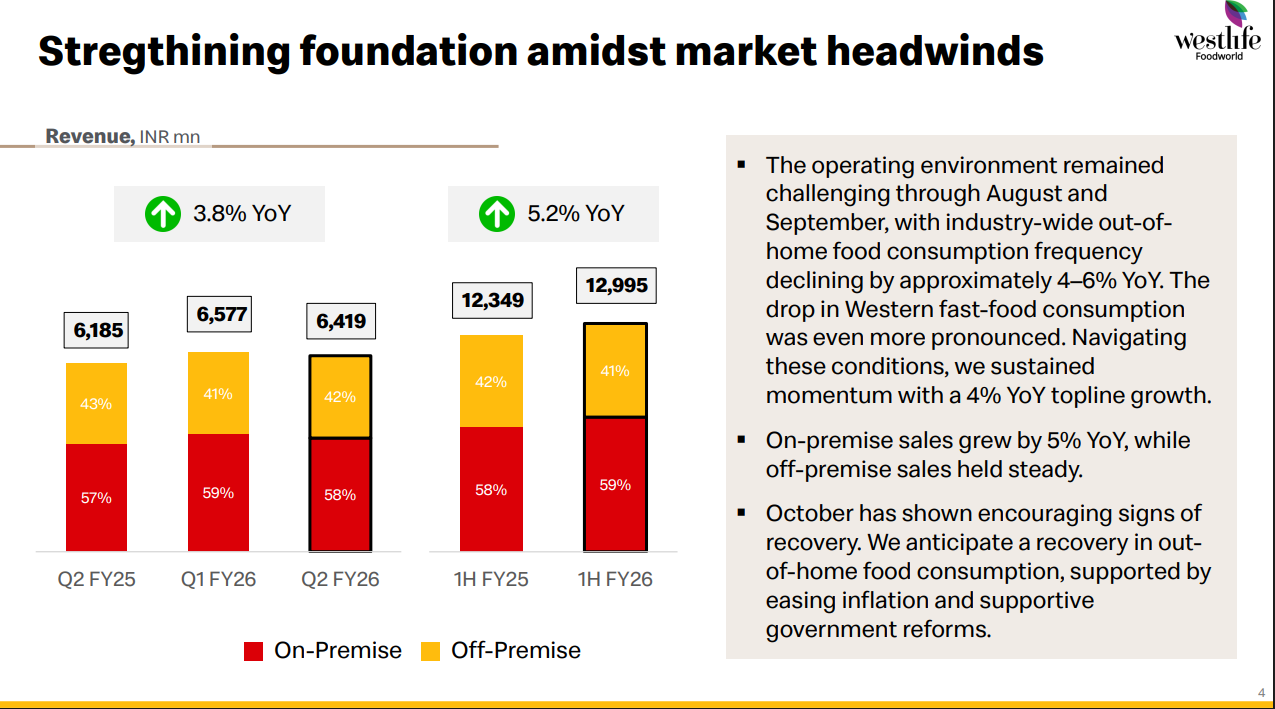

If Jubilant finally found coherence this quarter, Westlife lost it. The company’s performance was flat — with revenues growing by just 3.8%.

This wasn’t what the company had been messaging. For months, it kept saying that things were slowly improving — talking about “green shoots,” “gradual pickup,” or “progressively improving momentum.”

That illusion is breaking. This quarter, at least, none of that panned out. In fact, the company admitted what it had been avoiding for almost a year: fast food, it appears, is running out of demand. As Akshay Jatia, its CEO, said:

“For the first time, we’ve seen both the informal eating out as well as the QSR market actually contract.”

Not soften, not stabilise — but contract. That is, if McDonald’s is to be believed, the space for a business like this is shrinking.

Is that actually true? We don’t know. But one thing is for sure: Westlife simply isn’t able to push up same-store sales.

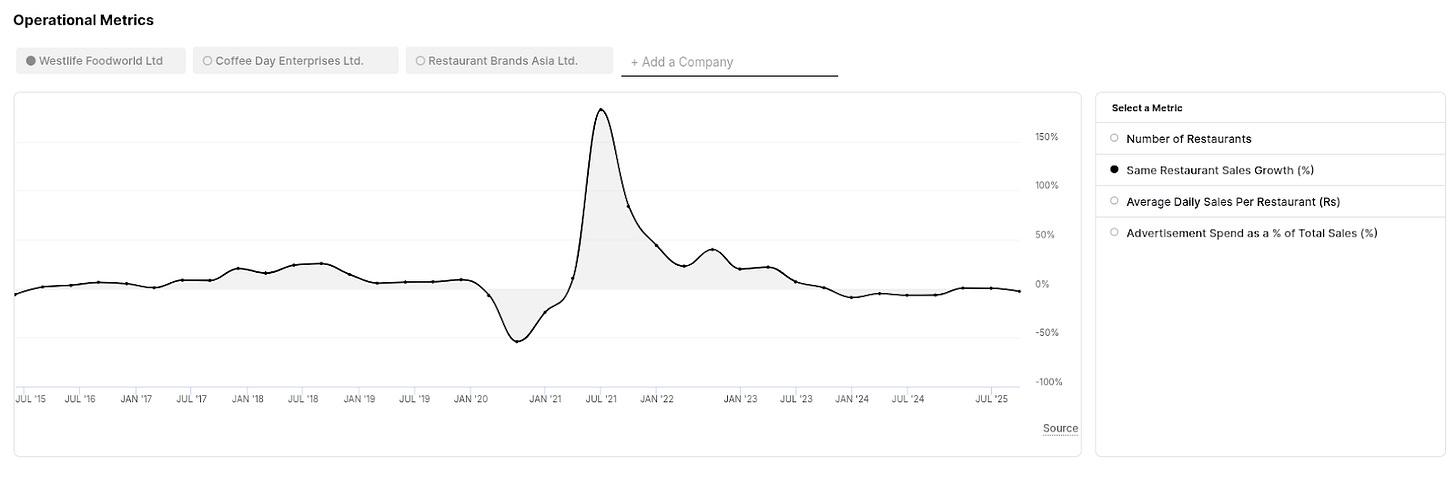

A company’s Same Store Sales Growth, or “SSSG”, tells you how much the sales of its existing stores have gone up in the course of a year. For over ten quarters, Westlife’s SSSG has gone nowhere. Its last spike in growth was its post-COVID rebound in 2021. After that, things have flattened and might even be drifting downwards.

When a chain has almost no SSSG for two years, the problem is no longer temporary; it’s structural.

South India, in particular, seems to be cooling on McDonald’s.

Westlife has 65–70 stores in Bengaluru — more than any city other than Mumbai. But Bangaloreans seem to have fallen out of love with the brand. According to the company, most of its negative growth came from Bengaluru alone, with both delivery and dine-in under “tremendous pressure”.

Not too long ago, the company was touting up a so-called “South turnaround plan” — with new experiments and leadership changes to stem the tide. Now, that plan has shrunk to, “We are doing small trials in one-one restaurants.” ,

This isn’t the only instant where their earlier optimism was misplaced. In May, the company said they were leaders on food delivery apps, and would “accelerate growth.”

It has now changed its tone. This quarter, it claimed that the performance of third-party platforms has been unstable.

Is there something that can pull McDonald’s out of its funk? For now, they’re betting on their in-house delivery service, “McDelivery” — hoping to double the platform in two years. Will this let them pull off Jubilant-like growth? We’ll check back in a few quarters from now.

No longer Finger Lickin’ Good?

It’s not just McDonald’s. Devyani International didn’t do that well either.

The company runs more than 1,700 KFC and Pizza Hut stores, apart from a portfolio of brands it owns: Vaango, and the newly consolidated SkyGate group, which houses Biryani By Kilo (BBK) and Goila Butter Chicken.

This widened Devyani’s customer base, opening up new segments. And yet, none of those segments came to its rescue.

There are some factors the company has no real control over. For instance, both the month of Shraavana as well as Navratri — when large numbers of Indians avoid non-vegetarian food — came within the same quarter. For a company whose business depends on selling fried chicken, biryani, and butter chicken, the timing was horrible. Meanwhile, the relentless rains hammered Pujo sales in East India.

But these were only surface-level drags. There are larger problems underneath. As the company’s CFO Manish Dawar said:

“Whenever, let’s say, we do some promotions or increase promotional intensity, it kind of picks up very well. And the moment you kind of withdraw that, it falls back…”

The company has buyers as long as it gives discounts — but they walk away once those discounts are gone. To the company, consumption is weak.

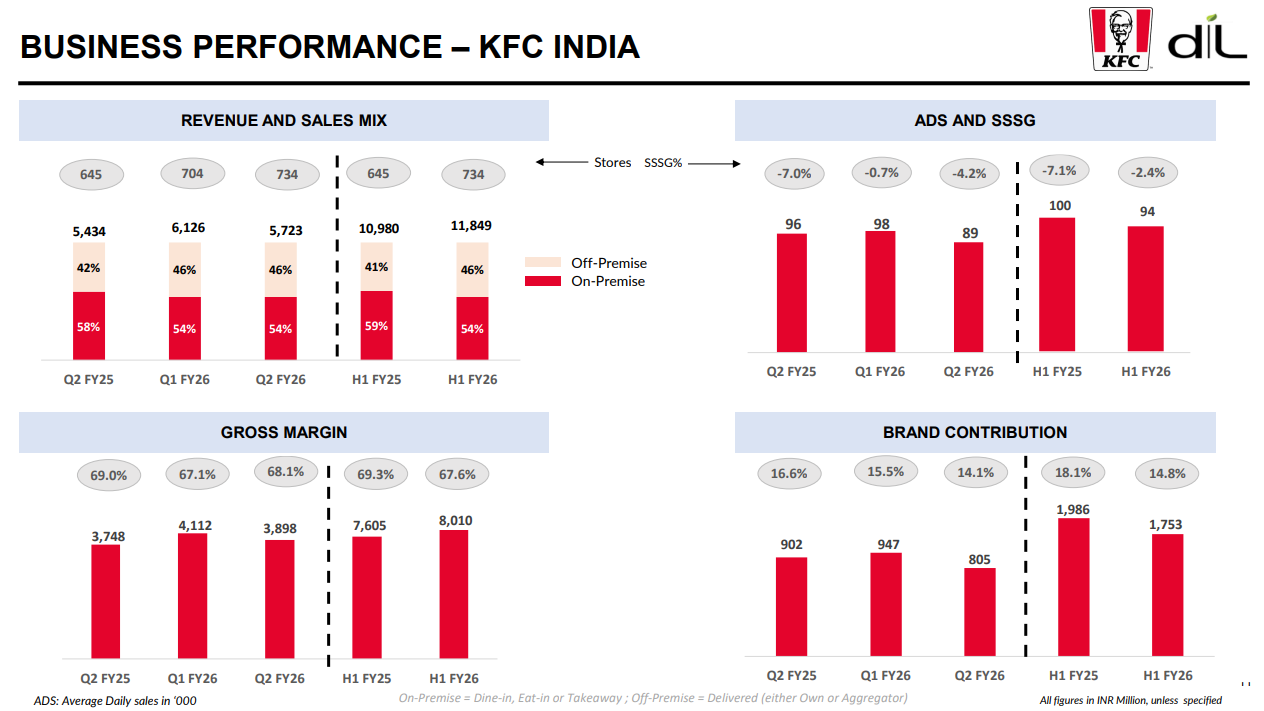

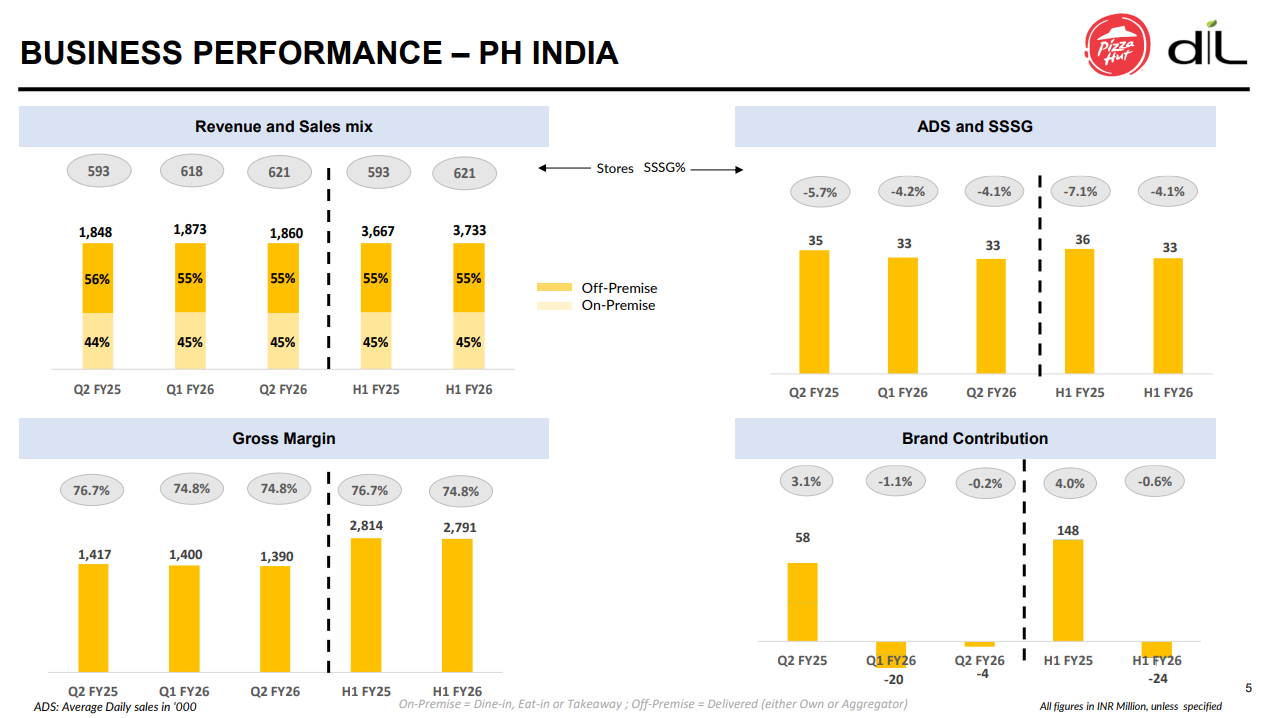

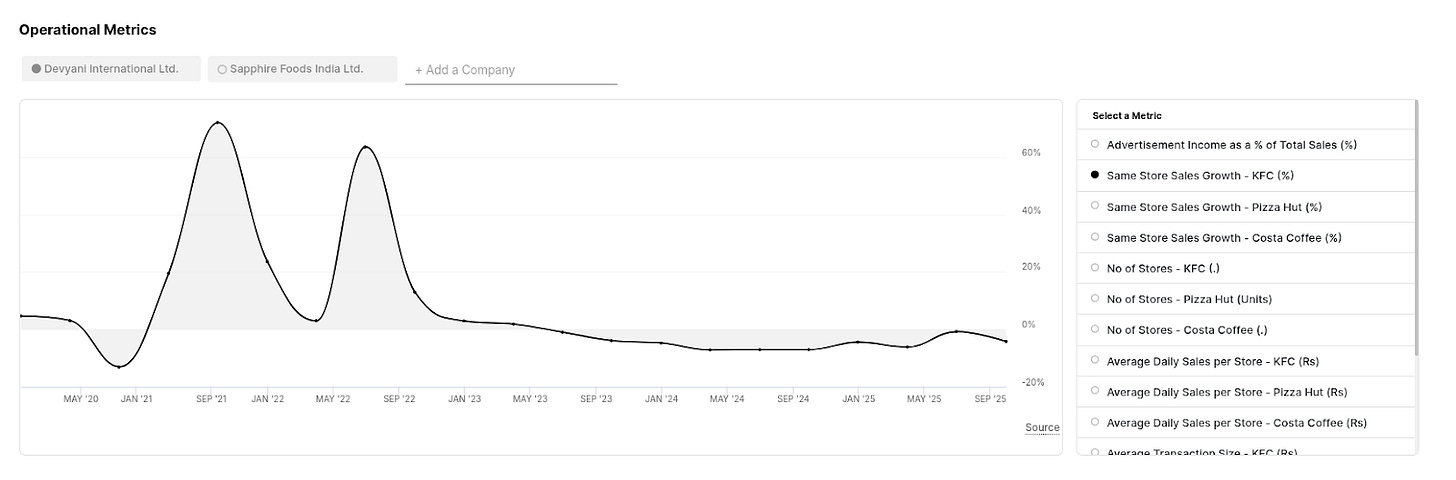

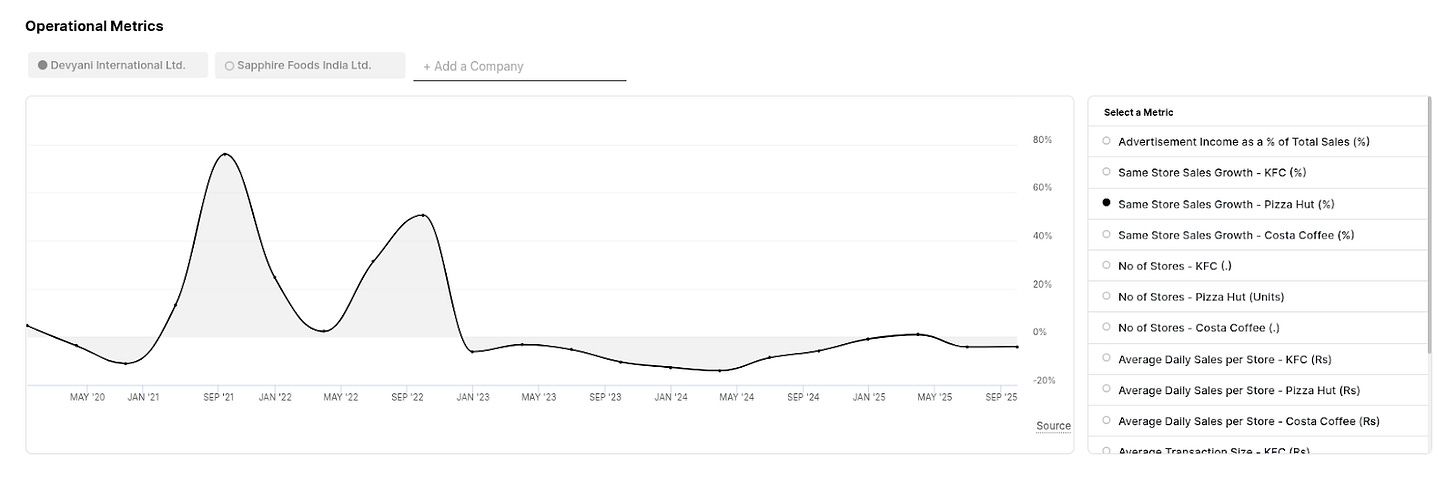

To be fair, Devyani still grew its revenues by 12.6% year-on-year. But most of that growth came because they opened new stores. The same stores, however, couldn’t draw more demand. The SSSG for both KFC and Pizza Hut was negative.

And much like Westlife, that has been the case for multiple quarters now. In particular, it simply isn’t pulling in dining-in customers, where the company gets its highest margins from.

As the company’s management says, this is an industry where SSSG can be a make-or-break factor. You can’t run this business without paying enormous fixed costs to run a restaurant. Those don’t go away when your per-store sales fall — if anything, they only grow larger with time.

But if KFC isn’t working, does the answer lie in new-age brands like biryani-by-the-kilo, or Goila Butter Chicken? While the business was loss-making, back in May, Devyani promised a turnaround within a year.

This quarter, that target has visibly softened. Now, it’s only hoping to break even “at a brand contribution level” within this financial year — that is, their unit economics will be sound, but the fixed costs may continue to pinch.

Similarly, Devyani had earlier promised a detailed Pizza Hut turnaround plan by August. Instead of presenting it, though, the management simply said they are “still in negotiations with Yum”.

While this wasn’t a disastrous quarter, clearly, Devyani has some serious problems. The heart of its business — same-store sales from a brand like KFC — has been knocked out. And it has slipped timelines on reviving the rest of its portfolio. This is a business with growing revenues; perhaps, its momentum is flagging.

Where does this leave us?

For the last two years, with the exception of Domino’s, no major fast food brand seems to know how to push up their SSSG. This is a bad sign. According to both Westlife and Devyani, this is a matter of cautious consumers and soft demand. But is it? And if it is, why are those same customers still ordering from Domino’s?

Is there a chance that customers no longer consider these fast food brands relevant? Is the incumbents’ loss not a matter of demand sentiment, but the sheer variety of competition in a food delivery era?

We’re not sure. But this is a question worth keeping an eye on.

Tidbits

POWERGRID–Nepal form JVs for cross-border lines

POWERGRID and Nepal Electricity Authority will set up two JVs—one in India (51:49) and one in Nepal (49:51)—to build 400 kV double-circuit transmission links. The projects include Inaruwa–New Purnea and Lamki–Bareilly lines, aimed at strengthening India–Nepal cross-border power flow.

Source: ET

India’s November business growth hits 6-month low

India’s private-sector growth slowed, with the Composite PMI slipping to 59.9, dragged by a nine-month low in manufacturing (57.4) despite stronger services. Firms cited heavy rains, soft new orders, and global pricing pressure. Export demand weakened as 50% U.S. tariffs hit overseas orders. Inflation eased, boosting expectations of an RBI rate cut next month.

Source: Reuters

GIVA targets 1,000 stores by 2028

Jewellery brand GIVA plans to triple its network from 280 stores to 800–1,000 over the next three years, with 150 new stores this fiscal alone. The company is deepening its presence in Tier-2 cities and building high-density networks in Bengaluru and Delhi-NCR, aiming for a store every 2–3 km.

Source: BusinessLine

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Krishna.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The diagnostics need doctors too. It's nowhere mentioned. I absolutely hate when people writing these long vlogs make these silly mistakes. Kindly rectify

Good article on food industries