Can two struggling businesses make a strong one together?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The biggest QSR merger: Devyani and Sapphire

The many small changes to India’s insurance business

The biggest QSR merger: Devyani and Sapphire

India’s quick service restaurant, or ‘QSR’, sector hasn’t been doing too well. Over the last few years, most QSR companies have posted net losses, while their per-store sales have been falling. This seems like a bad time to be in the fast food business.

We covered all of this in The Daily Brief previously.

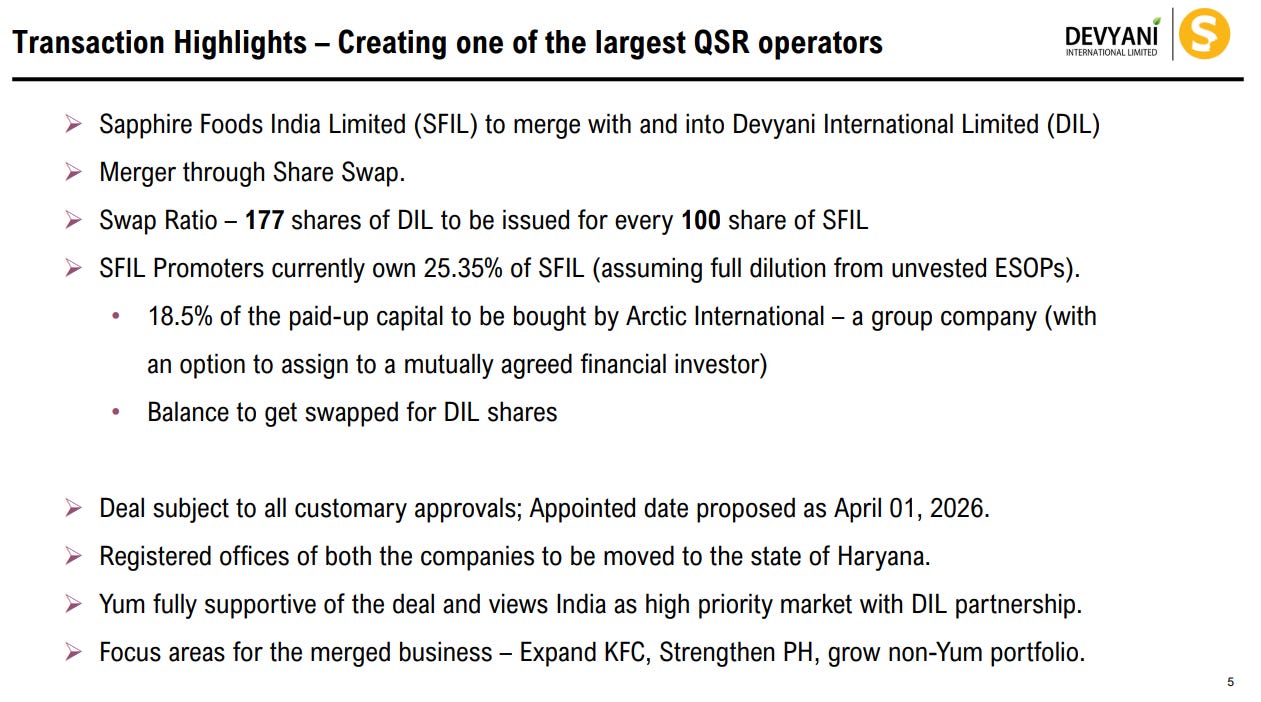

There’s a new development that confirms the industry’s tepid state — Sapphire Foods and Devyani International, two of India’s largest QSR companies, are merging. With this deal, Sapphire Foods shall no longer exist as a standalone listed company. It will be folded into Devyani International, and Sapphire’s shareholders will be issued shares of Devyani instead.

On paper, it looks like just another consolidation in India’s QSR space. But to us, this merger looks very different from how mergers usually work. That difference is what we want to explore today.

Two operators, one playbook

Before we get there, though, it’s helpful to know who these two companies are, what they actually do, and, more importantly, what they don’t do.

Both Devyani International and Sapphire Foods are, in a sense, mirror images of each other. They both operate most Indian franchises of Yum! Brands — the global company that owns KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and a few other famous fast-food chains. Yum! licenses its brands and know-how to the two companies. These companies take care of the actual day-to-day management — running stores, hiring employees, paying rent, sourcing ingredients (within strict rules), and executing everything on the ground.

Together, Devyani and Sapphire account for the vast majority of KFC and Pizza Hut stores in the country. They also operate in a few overseas markets, like Sri Lanka, Nepal, Nigeria and Thailand.

The twin businesses

The two companies share a unique relationship. They are, on paper, competitors. But their businesses are, in a sense, identical. They both run the same brands. And their operations, to a great extent, match those of each other.

The only major differentiator, perhaps, is that they both operate in different territories. Devyani has historically been stronger in the north and east of India. Sapphire has focused on the south and west.

This split is very much by design — it’s how Yum! structures its franchise relationships around the world. It doesn’t hand franchisees blanket licenses to franchisees to open stores anywhere. It signs “development agreements” which specify exactly which states or regions the franchisee can operate in. And so, if Devyani and Sapphire have thus far stuck to different geographies, it is because they contractually cannot encroach on each other’s territory.

These development agreements also lock both companies into very specific economics. Both franchisees pay Yum! a royalty on every rupee of sales, typically 5-6%. There are mandatory, pre-agreed contributions to national advertising funds. The companies also pay “technology fees” for using Yum’s systems.

They’re also limited in the business decisions they can take. For instance, both give minimum store-opening commitments — pushing them to expand at a certain pace instead of simply sitting on rights. They must also stick to strict guidelines on how the brand must be run — the menu, the recipes, the store design, the quality standards, all of which comes from Yum.

In short, both businesses are built around executing a common blue-print. And that’s why this merger is quite unlike the regular mergers we talk about.

Why this merger is different

Imagine two two steel companies that were merging. As commodity players, they probably sell similar products. But even so, they’re likely to be different in every other way. Each will have configured its operations in its own unique way. Their businesses will probably be structured in a unique manner. When they merge, a big part of the challenge would be integration — figuring out whose systems survive, whose processes are scrapped, and how they can best blend their two ways of running a business into one.

That problem barely exists here.

Devyani and Sapphire have never run their businesses “their own way”, to begin with. They operate inside a tightly defined global playbook. The entire point of this business model is that different stores should feel exactly the same in what they offer. Their menu is fixed; their recipes are fixed; their portion sizes are fixed. Their store layouts follow prescribed formats; the decoration they’re allowed is pre-defined, the cutlery they serve is decided centrally, and so on. Even their core technology systems — like their point of sale machines — are standardised.

This isn’t a business that allows unique models. You can only reshape how you execute the Yum! playbook. You can decide where to open stores, how you negotiate rents, how efficiently you can staff outlets, how tightly you manage costs, and so on. But ultimately, your role is that of a manager. The core business is designed elsewhere. All the most important decisions — what to serve, how to go about it, how to brand yourself, and so on — belong to Yum! Foods.

This is why the merger is unusual. These two businesses were designed to fit into each other like lego blocks. If anything, this merger is about removing an artificial split between two operators following the same playbook — turning them into a single, larger execution engine.

The slowdown, and the merger

So why merge now?

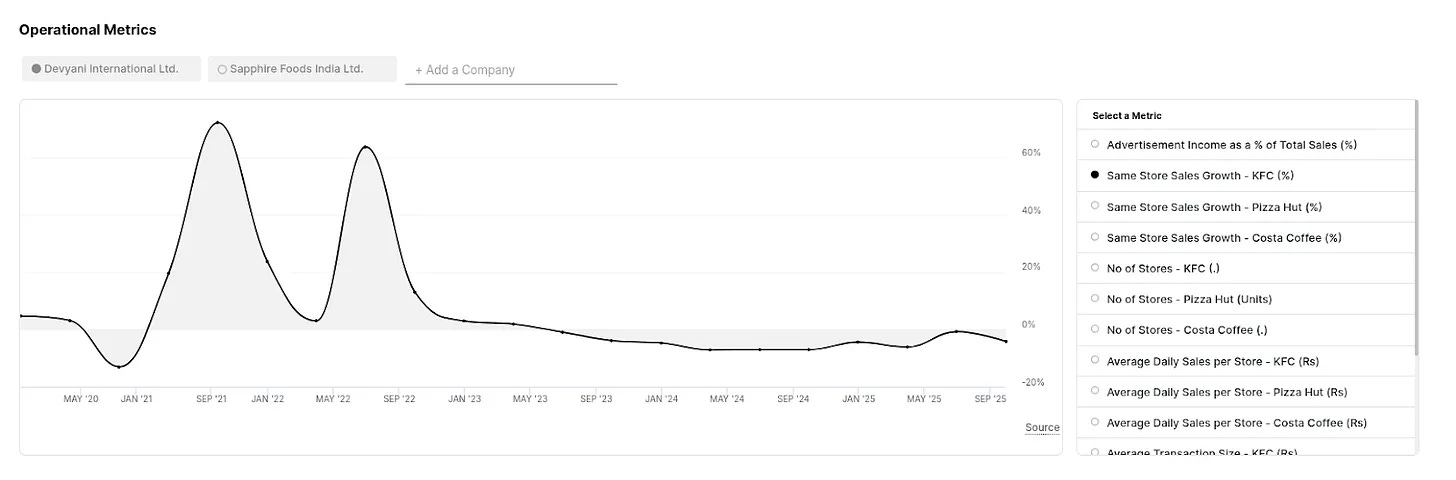

Well, as we told you at the start, for the past few years, the QSR sector in India has been under pressure. It had a good run after the pandemic, but that momentum has faded.

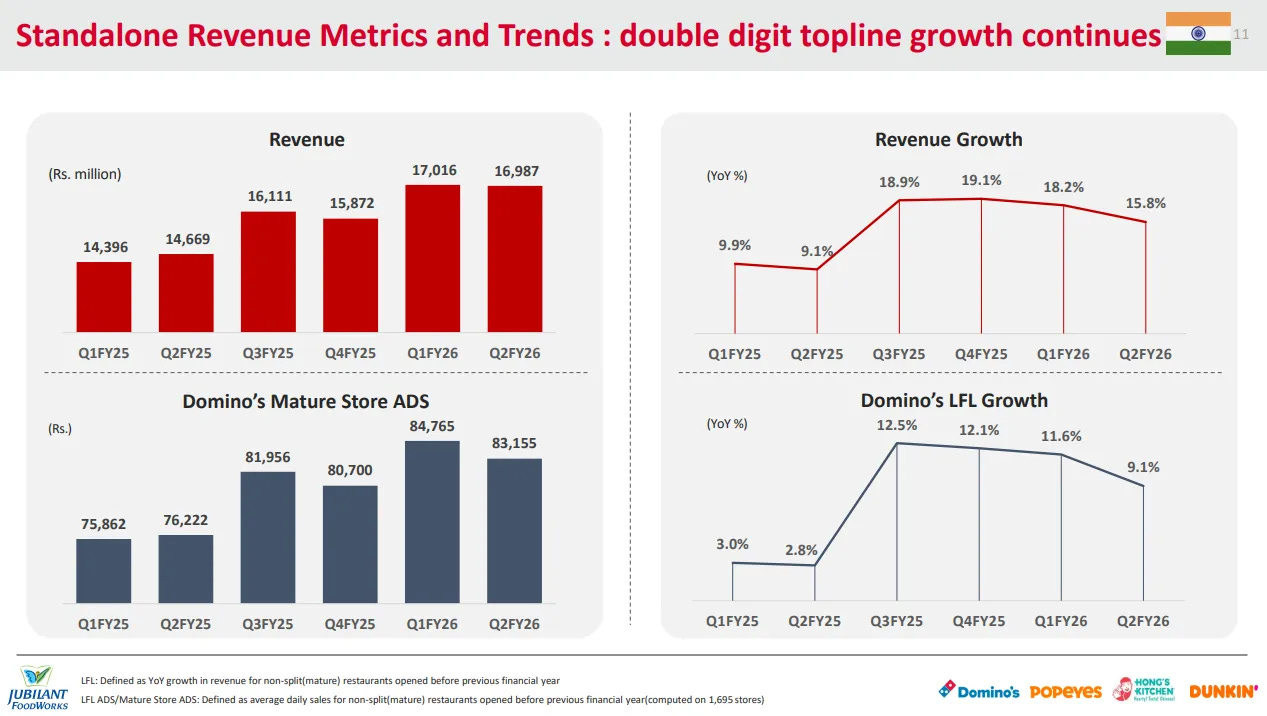

It’s not that people have stopped eating fast food altogether. Dominos, for example, is still doing well.

KFC and Pizza Hut, however, seem to be losing out — for reasons we aren’t entirely certain about. For both Devyani and Sapphire, same-store sales growth — which measures how much revenue existing stores are generating compared to last year — has been flat or negative for several quarters.

This is especially painful for franchisees, because a large chunk of their costs stay fixed, even if fewer people are walking in. Store rent, salaries, technology fees — all these payments have to go out on time, no matter how much business they do. Equally, their payments to Yum!, as franchisees, are calculated on gross sales, not profits. Even if they’re struggling to make money, the payments don’t cease. And so, as demand shrinks, they can suddenly slip into losses.

Unite and rule

The hope, with this merger, is that scale can bail them out.

Most importantly, they could cut down the “brand-level” costs they must pay to Yum! Individually, neither Devyani nor Sapphire has much bargaining power to change this equation. If anything, they balance each other out — if one pushes too hard, Yum can always point to the other.

That dynamic, perhaps, might change if there’s only one party to negotiate with. After all, post-merger, Devyani shall become the single largest operator of KFC and Pizza Hut in India — with a hold on most of their stores. This could, ideally, give them room to negotiate temporary waivers, or seek relaxations on the guarantees they’ve given around store openings and closures.

You can already see hints of this in what’s been disclosed.

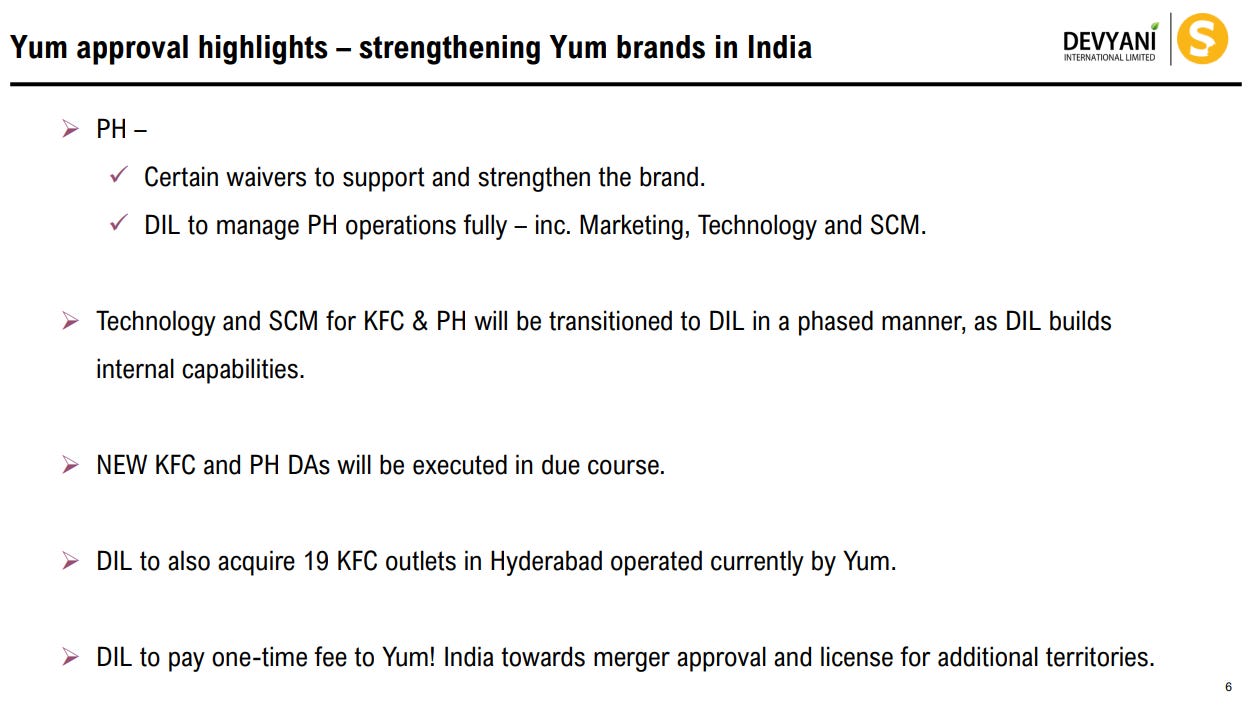

Yum has explicitly approved the merger, and has agreed to certain waivers to support Pizza Hut. It is also transferring 19 KFC stores in Hyderabad, which were earlier operated directly by Yum itself, to Devyani. Devyani is paying Yum a one-time fee for these changes — which is essentially the price of rewriting the relationship, and gaining all this flexibility.

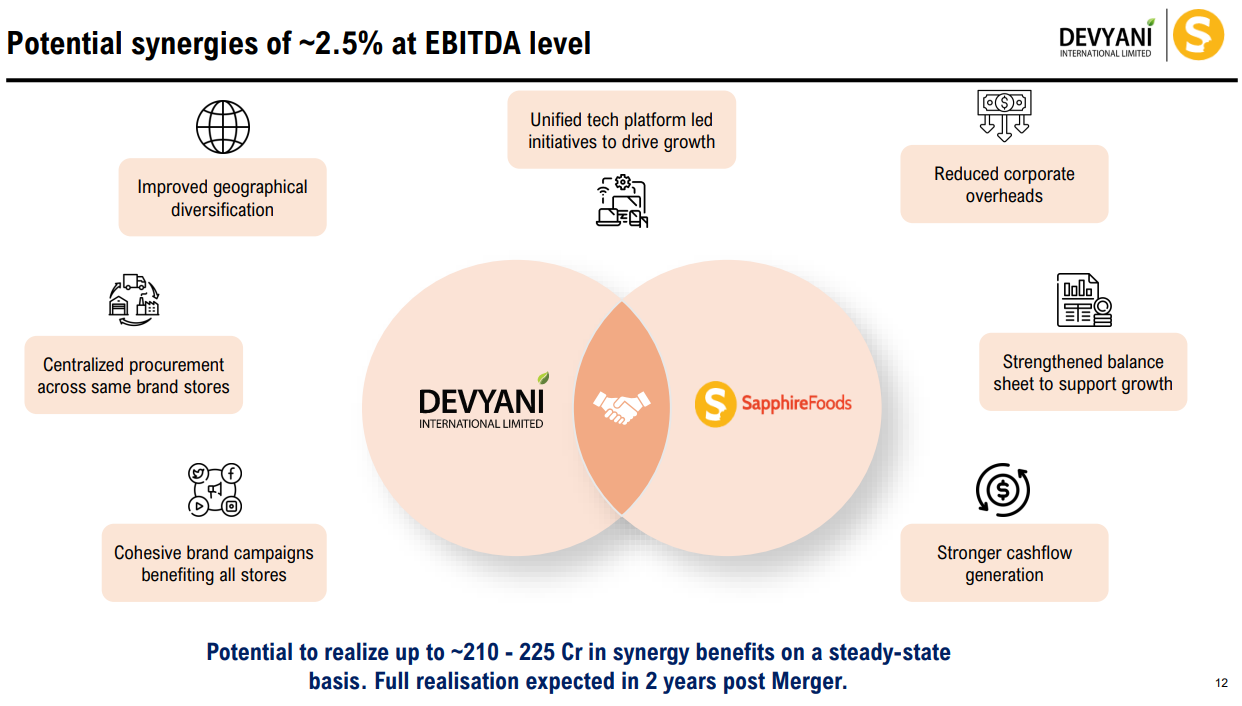

This new bargaining power is the single biggest source of the much-discussed ₹210–225 crore in “synergies” the merger supposedly unlocks.

Co-ordinating as a single entity

There is also a more subtle, but important, benefit around decision-making.

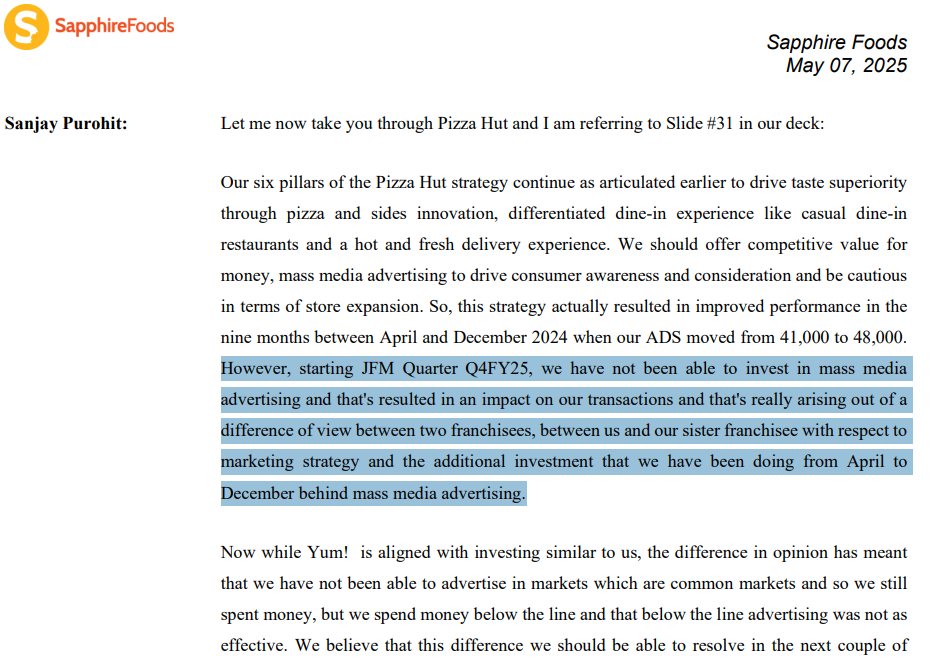

A hidden cost of having multiple franchisees running the same brand is the possibility of a coordination failure. Sapphire alluded to this in its March 2025 earnings call, when management said:

“However, starting JFM Quarter Q4FY25, we have not been able to invest in mass media advertising and that’s resulted in an impact on our transactions and that’s really arising out of a difference of view between two franchisees, between us and our sister franchisee with respect to marketing strategy and the additional investment that we have been doing from April to December behind mass media advertising.”

Simply put, two companies running the same brand couldn’t agree on how much to spend on advertising. Those advertisements would have benefited both companies, but for that benefit, they would both have to contribute. And they couldn’t hammer out how to do so. And so, advertising just stopped, and as a result, footfall dropped.

This seems like one example of a larger, structural problem. If you need two companies to align on anything, it’s only reasonable that things fall between the cracks every now and then. Decisions that should take a week take a quarter. Merging into a single operator, at least in theory, fixes that.

There are no guarantees

At least, that’s how it sounds on paper. But none of this guarantees success.

The QSR sector is still in a difficult phase. And mergers come with many points of failure; some of which could erupt even if these businesses are functionally identical.

Most importantly, the promised savings will only materialise if management is willing to make tough calls — closing underperforming stores, simplifying structures, and actually using the leverage the merger creates. Without that, it’s hard to see how combining two struggling businesses might create a strong one.

The many small changes to India’s insurance business

Every six months, the RBI puts out a thick document called the ‘Financial Stability Report’ (FSR). This doesn’t tell you what’s happening in our financial sector right now, exactly. Most of its numbers are backward-looking by design. They’re out-dated by definition; they tell you what the system looked like a few months ago.

But what the FSR loses in timeliness, it makes up for in its sheer granularity.

The report is a remarkable magnifying glass trained on India’s financial system — seeking hidden clues like a detective on a crime scene. These aren’t patterns that come up in headlines or in quarterly results. Nor are they apparent when you’re looking at broad averages and top-line figures. But they are important if you really want to understand what’s happening under the hood of the sector.

When the RBI released its latest FSR on 31st December, we decided to ignore the high-level picture it painted, instead hunting for the strange, under-discussed bits. And today, we’re only looking at the insurance sector, specifically — pulling out a few story-worthy trends. In coming episodes, we’ll turn to some of the other sectors the report talks about.

When insurance business model breaks

A vanilla life insurance business is straightforward.

Premiums come in regularly. Payouts go out at known points. For products with fixed maturity dates, the timing is almost certain, of course. But even when you’re settling claims, while you can’t predict when a specific person dies, in the aggregate, you can model your pay-outs over broad periods through actuarial models.

That predictability is what makes the insurance business work. If an insurer knows — at least roughly — when money shall leave their accounts, it can plan how to invest premium inflows without constantly worrying about sudden liquidity crunches.

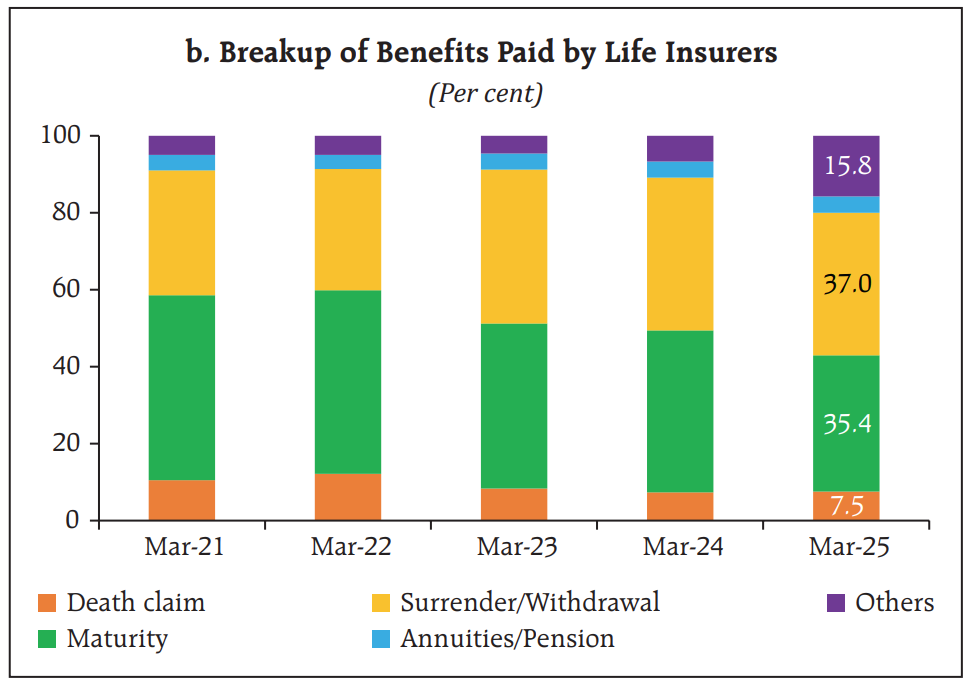

But the RBI flags something that messes with this neat picture: over the last few years, the share of payouts that insurers are making towards scheduled maturities has fallen, while the share going toward surrenders or withdrawals has risen.

Simply put, more people are exiting earlier than expected.

Think of it like this: imagine an insurer thought it could invest some money for, say, 10–15 years, and put it into something that will take a decade to mature. Only, policyholders start pulling out in year 2 or 3 itself. The insurer is suddenly forced to arrange for cash immediately. The insurer may well have the assets it needs to pay everyone, and yet, a lot of that money could be locked away in long-term investments, creating a sudden crunch.

But why are these early exits rising? The RBI doesn’t give us any answers, but to us, there are a few possible explanations:

Maybe, there are some policies that are being pitched as “protection”, but buyers treat them like a savings product that they don’t mind breaking early?

Maybe there is genuine mis-selling — buyers are sold policies as “investments”, and only later realise that this product wasn’t what they thought it was?

Or maybe there’s simple household cash-flow stress, and people need their money back because, well, life happened?

Whatever the reason, this trend is worth watching. Insurance is supposed to be a long-duration business, and if early exits change that dynamic, it could fundamentally alter how the industry behaves.

Private insurers got no chill

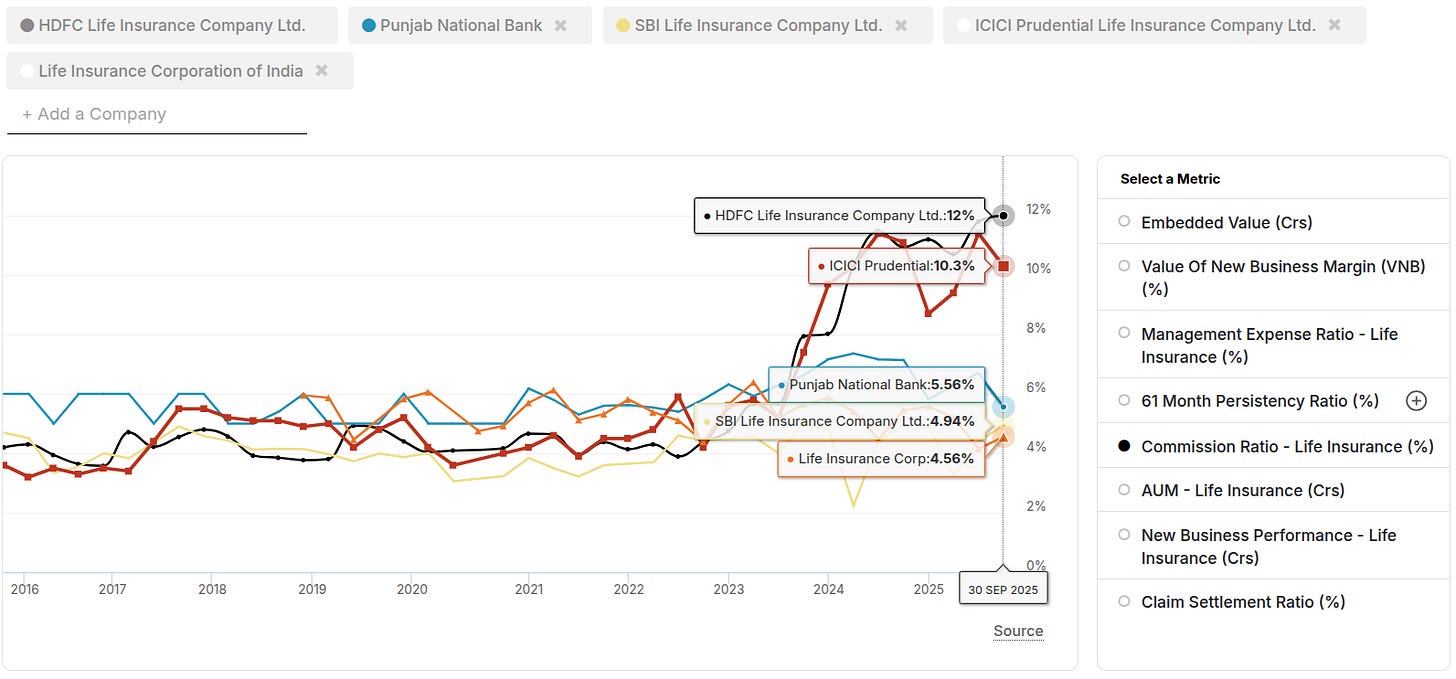

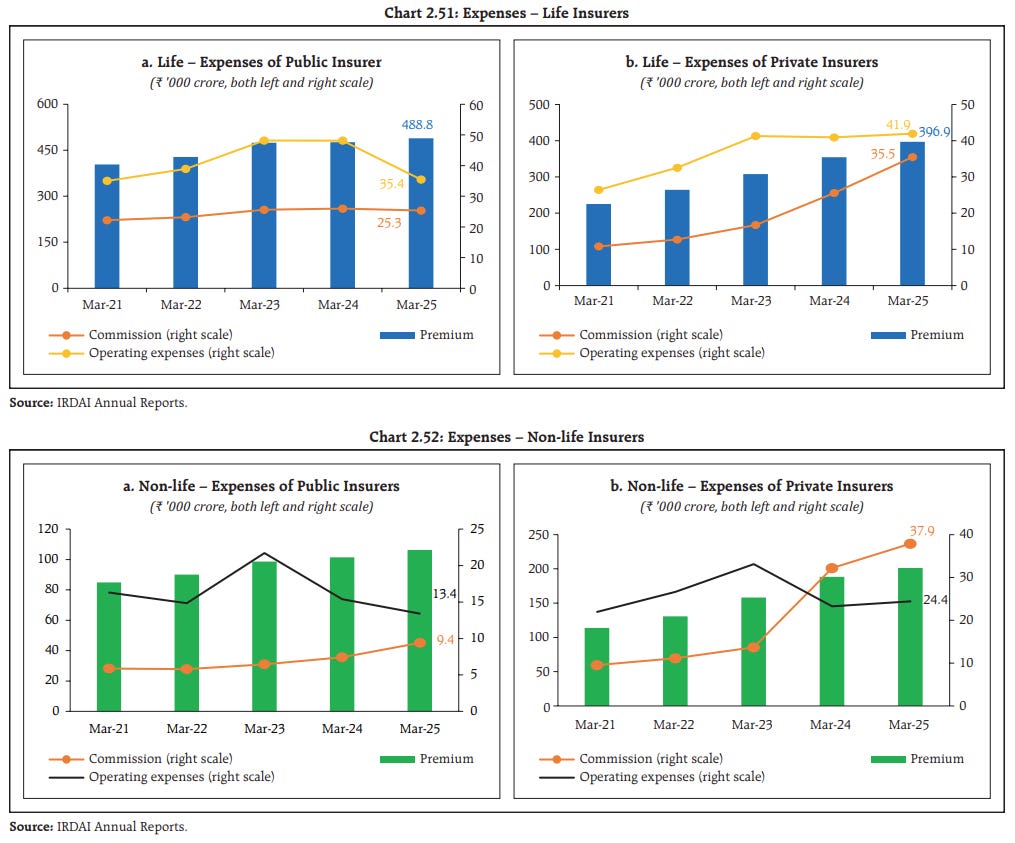

The RBI points to a major difference developing in how public and private insurers are behaving with costs — especially commissions.

Commissions are what insurers pay their entire distribution machine: agents, intermediaries, or whoever is selling the product. And they’re the biggest expenses in the insurance business. They make anywhere between 40-50% of an insurer’s total operating cost, once you exclude claims.

That’s understandable; at least in India, insurance has historically been a “push product”. It has been sold by agents, often sweetened with investment or tax benefits, rather than being sought by customers who feel the need to manage risk. This isn’t universal; there’s a shift towards a “pull” model underway, but that’s still in its early days.

But there’s a new divergence that the RBI spotted: while public sector insurers have kept commission structures relatively flat and steady, private insurers have been paying an increasingly higher share out as commissions in recent years — both on life and non-life sides. This divergence started becoming especially clear after 2023.

Now, this can ripple through the entire industry, because distribution is competitive. When one insurer pays better, it creates a strong incentive for a seller to push that specific product.

We’re seeing exactly that. Lately, private insurers have been taking away market share from public insurers. There’s a good change that they might be buying that extra growth by paying higher commissions.

But this strategy comes with risks.

For one, like money spent on acquiring customers in any industry, these payments can come at the cost of profitability. Unless a customer sticks around long enough for a policy to become profitable, the insurer can simply end up losing that money. In a time where surrenders and withdrawals are rising, a model based on high commissions can push an insurer into losses.

Of course, insurers won’t stomach the entire cost. Instead, they’re passing those costs on to policy-holders, in the form of higher premia. Ideally, as insurance businesses scale, their operations should become more efficient, making it cheaper to do business. That cost should be passed onto policyholders. But instead, as insurers pay high acquisition costs to get a customer, they’re making those customers pay more as well.

This creates a weird paradox: India’s insurance density — the average premium paid per person — has steadily risen from $78 in 2020–21 to $97 in 2024–25. However, insurance penetration has basically stalled.

In simple terms: the average policyholder is spending more, but the number of people buying insurance isn’t really growing. Which suggests that rising costs — or just poor affordability — may be pushing people away and limiting broader inclusion.

The foreign dependency

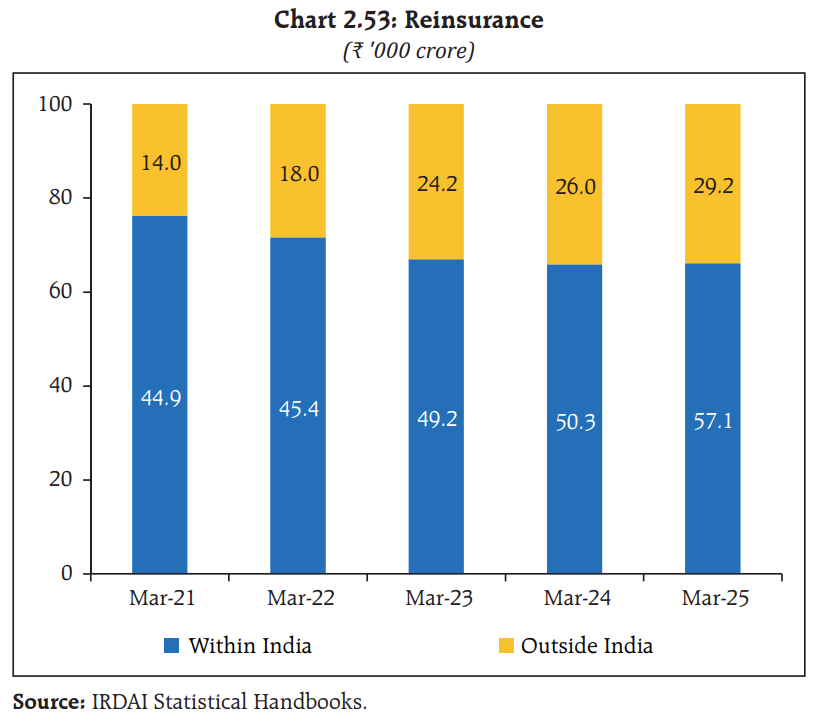

The FSR also has some interesting observations on reinsurance.

A reinsurance company, at its heart, insures your regular insurance companies. They’re like super insurers; they promise to absorb the risk arising from large parts of the portfolio of an insurer, allowing them to take more risk. This makes reinsurance very fundamental for the maturity and growth of a country’s insurance sector.

Now, at a high level, things look fine for India’s reinsurance industry. Our overall domestic reinsurance market is expanding. Interestingly, however, it isn’t growing as fast as the primary insurance market. That is, more and more of India’s reinsurance demand is being met by foreign reinsurers.

As per the data, the amount of reinsurance business ceded within India has risen roughly ~1.3x over the last few years. But the amount ceded outside India has grown much faster — more than doubling over the same period.

In absolute terms, India still cedes almost twice as much reinsurance domestically than abroad. But evidently, the share of cross-border reinsurance is creeping up.

This points to one thing, above all else: capacity constraints at home. We’ve talked about this problem of reinsurance in depth earlier — but basically, India only has one full reinsurer — the PSU General Insurance Corporation of India. Its monopoly has been upheld through complex rules that give it a first right of refusal. But as we discussed then, GIC simply can’t take up all the business Indian insurers have to offer.

This is worrying, because reinsurance isn’t just a safety valve; it’s also an economic opportunity. If domestic capacity is limited, we end up exporting premium outflows, importing pricing and terms, and building a structural dependency for catastrophe and specialised risks.

This is also why it is important to expand domestic reinsurance capacity — by making it easier to set up and scale reinsurers in India. This is also why we felt Jio’s entry in this space in partnership with Allianz is a big deal, that’s worth tracking. We need more such partnerships in future.

Not so obvious GST Angle

Finally, the RBI mentions an interesting, new factor that’s impacting the business: an exemption on paying GST for individual life and health insurance premiums, which was introduced in September 2025.

At first glance, this is obviously a consumer-friendly move, as it lowers the effective cost of premiums. This should help more people to buy insurance, therefore improving penetration.

But there are bigger, more macro-level ripple effects that the RBI is tracking.

Consider this: as insurance becomes more attractive, premiums shall rise. Insurers will be sitting on a larger pool of long-duration liabilities. Such long-duration liabilities are exactly what you need to fund sovereign bonds, infrastructure assets and other long-term investments the economy needs. The World Bank too acknowledges how insurers are “natural providers” of long term capital.

In other words, as “insurance gets cheaper”, an economy receives more long-term capital to take up investments. The GST cuts, in short, can be seen as an attempt at building domestic long-term capital. This is money that originates within India and can stay invested in Indian assets. And that, in turn, decreases our reliance on foreign pools of long-term funding.

Will this play out cleanly? That isn’t guaranteed. But it’s an interesting connection to think about.

What next?

We’ve barely scratched the surface of what the RBI’s FSR has to offer. It has far more on banks, markets, and household finances than we could fit into one story. We’ll likely return to some of that in our stories ahead.

Tidbits

NTPC ties up with Russia, France for nuclear expansion

NTPC has signed non-disclosure agreements with Rosatom (Russia) and EDF (France) to explore large nuclear power projects in India. The talks cover the full project lifecycle as India looks to open up nuclear power to private and foreign players. NTPC is targeting 30 GW of nuclear capacity by 2047.

Source: Economic Times

Vodafone Idea hit with $71 million tax penalty

Vodafone Idea has received a ₹638 crore ($71 million) GST penalty for alleged short payment of taxes. The order came just a day after the government granted the telco a partial moratorium on AGR dues, dampening investor sentiment. The company said it disagrees with the order and will challenge it legally.

Source: Reuters

TCS says AI push is delivering real results

TCS says its shift toward becoming an AI-led technology services firm is already paying off. The company has reached $1.5 billion in annualised AI revenue, completed 5,000+ AI engagements, and deployed 200+ AI platforms globally. Over 180,000 employees have now been trained in advanced AI skills.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉