A new pillar for Indian insurance

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Jio and Allianz dive into reinsurance

What oil prices actually mean for inflation

Jio and Allianz dive into reinsurance

Here’s some big news: Mukesh Ambani’s Jio is teaming up with the German financial services giant Allianz, in a bid to shake up yet another industry.

Only, this newest partnership is in something as unglamorous as reinsurance. That’s a sector that hardly ever makes headlines in India — largely because it’s been the sleepy domain of a single, government-owned player for decades. So far, this has been a staid, boring business — one that regularly handles lakhs of crores, but one where nothing exciting every happens. But that might be changing, with the announcement of the new 50:50 reinsurance joint venture between Jio Financial Services and Allianz.

The move prompts a bunch of questions: Why reinsurance, of all things? Why now? And what does it mean for India’s insurance industry, which has so far treated reinsurance as an afterthought?

To answer these we need to take a detour in understanding reinsurance first.

What in the world is ‘Reinsurance’?

If insurance is a safety net for regular folks and businesses, think of reinsurance as the safety net for insurance companies themselves. Simply put, reinsurance is insurance for insurers.

Insurance companies often get on the hook for a huge risk. For instance, they might end up writing too many property insurance policies in an earthquake-prone area, only to realise that a single bad day could rake up billions in claims. Naturally, they don’t want to shoulder all that risk alone. If they do, a single catastrophe or a mega-claim could bankrupt them. So they reinsure a portion of it with bigger, specialized insurers — reinsurers.

Insurance companies do that by ceding a portion of the premium they collect, so that reinsurers pay their share of any big claims.

This keeps the insurance industry going as a whole.

Without reinsurance, insurance companies would play it extremely safe, refusing to insure anything too big or too risky, or charging sky-high premiums to cover their backs. Moreover, an insurer’s ability to take all risk will then be limited by the capital they have — and despite having the expertise and reach to write more policies, they may quickly have to shut their books. Both aren’t good for the industry.

Re-insurance solves this problem. In essence, they help insurance companies do their job much better than they would have otherwise.

With the basics covered, let's focus now on India's reinsurance space.

GIC’s Monopoly and the Quiet Decades

If reinsurance is so important, you’d think there’d be a bustling market for it in India. Not quite.

For over 50 years, India effectively had a single reinsurance company – the General Insurance Corporation of India, commonly known as GIC Re. Early on, the company’s four subsidies were the only ones you could go to for general insurance as well. The entire industry basically belonged to a single family of PSUs. When the industry was opened up in 2000, however, GIC stepped back, and became a pure reinsurer.

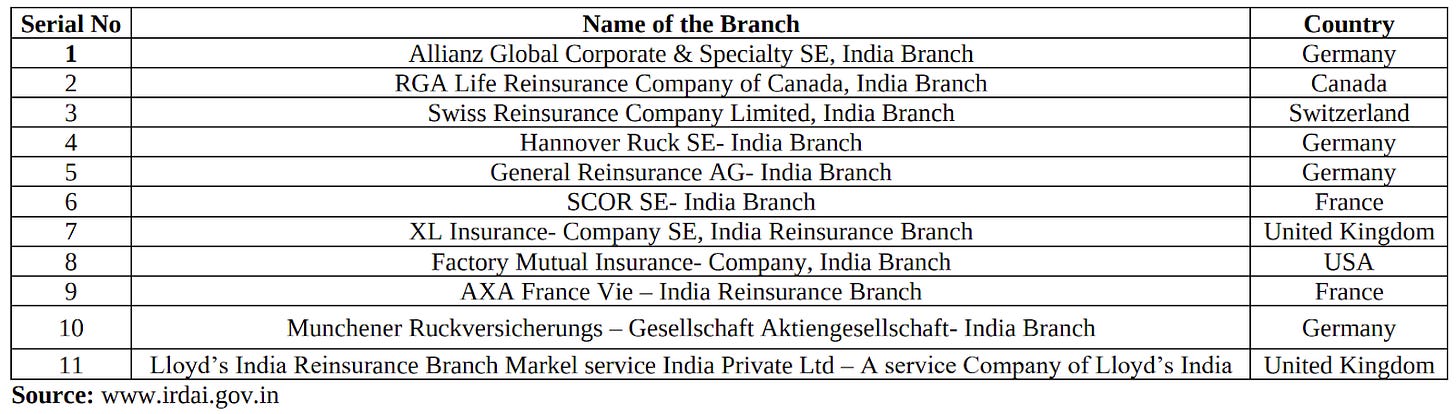

But its reinsurance monopoly continued even after 2000. Until 2016, in fact, GIC Re was essentially the only game in town for Indian insurers looking to cede risk. Things only started changing when IRDAI allowed 11 foreign reinsurers to set up local branches — Foreign Reinsurers Branches (FRBs).

Even then, regulations continued to favor GIC in two major ways:

Obligatory cession: Indian non-life insurers had to transfer a fixed percentage of their risks to GIC. Initially around 10-15%, this figure may now come down to 4% FY26 onwards for certain sectors. Even so, if a health insurance company offers a policy with ₹1 crore coverage, for instance, it must mandatorily cede ₹4 lakh worth of coverage to GIC.

Pecking order: Insurers had to offer reinsurance deals to GIC first. Only if GIC declined could insurers approach others. This rule was only softened in 2023, when IRDAI placed Indian reinsurers and FRBs on equal footing.

To be fair, this wasn’t just short-sighted protectionism. The intention behind GIC’s protected status was noble. Insurance companies deal with mind-boggling sms of money, and this helped retain some of that money within India, while building local expertise. And these regulations did make GIC Re one of the world’s larger reinsurers by volume.

That didn’t save the company from stagnation, however.

These legal safeguards should, in theory, have meant that GIC would utterly dominate the re-insurance business in India. But that wasn’t entirely the case. Despite its massive advantages, once foreign reinsurers set foot in India, GIC started bleeding away market share. Between 2019 and 2023, its market share (by premiums) dropped from 74% to 51% — even before regulations were softened.

This made us wonder: Why was this happening despite favorable rules?

We spoke to some industry experts on this, and a few things became clear. Apart from foreign players coming into the market, there were other key factors at play.

Capacity constraints.

The first was capacity constraints.

Just because insurers offered their business to GIC didn’t mean GIC could always take it. It only had so much capital, and so, there were only so many policies it could reinsure. Once GIC hit these internal limits, insurers had no choice but to look elsewhere.

There were also limits to GIC’s expertise, especially as the Indian insurance market grew rapidly. See, reinsurance is quite technical. GIC has always excelled in standard, predictable areas — motor, health, property etc.. But as insurers expanded into specialized and complex areas, like cyber risks, or catastrophe bonds, they naturally gravitated toward global players such as Munich Re and Swiss Re — who were known worldwide for their innovation and specialized knowledge.

Risk management

Reinsurers themselves follow basic principles of risk management. It's always better for a reinsurer to diversify risk across products (life, fire, health, marine, natural calamity, crop) and geographies (North America, Europe, Middle East, etc.). By diversifying, reinsurers make sure that a huge concentration of risk doesn’t land on their books, allowing them to take on risk from insurance companies at affordable rates and still turn a profit.

Foreign reinsurers, with highly diversified global portfolios, had a clear advantage over GIC. Even though GIC operated internationally, nearly 70% of its business was still domestic. Foreign players, with a broader global customer base, could mitigate their risks better and offer more competitive terms. This allowed them to consistently outperform GIC on pricing and terms.

Reinsurers also sometimes offload portions of their risk onto others, a practice called retrocession — essentially reinsurance for reinsurers. GIC Re of course does its own retrocession – it passes on some of the risk it can’t handle to other reinsurers. That creates a unique dynamic. GIC’s rivals are the very companies it cooperates with to share risk.

When it came to India’s reinsurance industry, GIC was like a single pillar holding up the roof, instead of a network of pillars supporting each other. With no local competitors to share risks with, GIC had to rely on foreign retrocession for very large exposures.

The Allianz-Jio Relationship

With that, we come to this new chapter in the reinsurance industry.

Jio-Allianz’ entry into this business is interesting. Unlike some of the other businesses it has disrupted, this isn’t a winner-takes-all market. If Jio and Allianz actually enter the reinsurance business, it would strengthen the whole industry — GIC included.

At the same time, this also marks a new chapter in Allianz’ foray into India’s insurance industry.

This new partnership follows the breakup of one of India’s long-standing insurance joint ventures: Bajaj Allianz. For 24 years, Allianz was a junior partner (26% stake) in two highly successful insurance companies with the Bajaj Finserv group — one in life insurance and one in general insurance. These JVs were cash cows — they were among the top players in the industry, while consistently staying profitable and growing. Together they collected over ₹40,000 crore in premiums annually.

But Allianz had to walk away.

See, when Allianz accepted its role as junior partner in the joint venture, that was all it was allowed to do by law. Foreign players couldn’t hold any more than 26% of an Indian insurer. But those rules were eventually relaxed. And Allianz, a global giant, naturally wanted a bigger slice of the pie in India.

But for that, however, they’d have to convince Bajaj to give up control — something it had no reason to. Why cede control of a massively profitable venture, after all? By early 2025, it became clear that Allianz’s aspirations and Bajaj’s plans no longer aligned. And so, Bajaj Finserv agreed to buy out Allianz’s 26% stake. We covered this when the news broke.

Back then, Allianz politely noted it would reinvest the sale proceeds into new opportunities in India. It was trading up for a new partnership where it could have equal footing. That’s where Jio Financial Services came in.

When Allianz had first entered India, it did so in a landscape where no other private player knew how the insurance game was played. It brought that global insurance expertise to India, seeding a now-thriving industry. It now seems poised to do the same with another business that it was already doing abroad — reinsurance.

So here we are: Allianz and Jio have agreed to form a reinsurance joint venture — although that’s non-binding at this stage. This time around, however, it isn’t a junior partner. It’s entering this business as an equal with Jio, with a 50% stake and equal share control. In addition, the two may also potentially open two insurance companies (one life, one general) as 50-50 JVs down the line.

This new reinsurance tie-up may just be one of the most interesting developments in India’s insurance space in years. More competition and more capital in reinsurance could mean Indian insurers can underwrite more policies and larger risks with lesser fear, knowing they have multiple avenues to hedge those bets.

What oil prices actually mean for inflation

There’s a standard truism that all Indian investors know: we, in India, are perennially dependent on the rest of the world for our energy needs. When global crude oil prices go up, those prices always trickle into the Indian economy. A lot of our inflation is a simple question of where the world’s oil prices currently are.

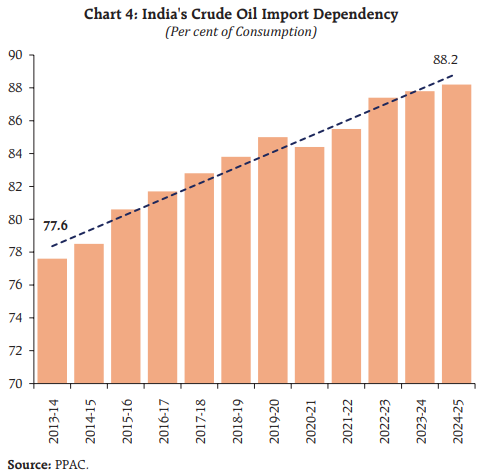

We’re not unique in this. Whenever something shakes up crude oil prices, prices seem to jump up all over the world. But the scale at which this happens changes from country to country. India is particularly vulnerable — with over 85% of our oil requirements coming from abroad, every wild swing in global oil prices yanks our economy along for the ride.

This, of course, isn’t news. This dynamic has existed for as long as we’ve been a globalised economy. All the way back in the 1970s, unrest in the Middle East created a decade-long inflation episode in much of the world.

So why talk about this now? Well, the last few years have been wild. In the last five years, oil prices have moved all over — from an average of $44 per barrel in the first year of the pandemic, to more than twice that — $93 per barrel — by 2022-23, to under $70 in the first half of this year.

In short, oil prices have been incredibly volatile in recent memory. Dealing with so much churn can be terrible for an economy like ours. That’s why it’s important for us to understand what, precisely, these shifts in oil prices do to our economy.

The RBI just released a new paper that talks about exactly how this happens. That’s what we’re going to dig into today.

How changes in oil prices turn into inflation

There’s a simple version of this story; one that you probably already know. Fuel, to most people, is one of their biggest monthly expenditures. It takes up 9% of our retail inflation basket. When global crude oil prices go up, people spend more on fuel — hence causing inflation.

It isn’t really that simple, though. There’s much more happening behind the scenes.

Direct channel

None of us actually purchase crude oil. We go to petrol pumps and fill our vehicles at whatever price they quote. When the price of a barrel of oil sitting somewhere in the Gulf changes, that change won’t hit your wallet directly. What you pay reflects international crude prices, but that’s not all it’s made of. There’s a long series of things that separates you from actual crude oil prices.

First come the refiners — companies like Reliance. They’re the ones that directly deal with crude prices. But that’s not all they pay for — even before that oil reaches them, they manage shipping prices, insurance, and exchange rates. They get into complicated hedging arrangements to manage their costs. And once the oil reaches their refinery, they face another layer of costs — operations, technology, and more.

At the other end, they set an “ex-refinery price”: a mix of all these costs, their own profits, and what their competitors are charging for finished petrol and diesel. This is the price at which they sell refined fuels to another set of entities — “Oil Marketing Companies” (or OMCs).

OMCs like Bharat Petroleum or Nayara carry fuel to your neighbourhood pump, marking the price up further to cover their own margins. Their pricing decisions are usually based on what you can actually pay. They don’t always pass every wiggle in crude prices straight through — they manage their inventories to keep things as cheap as possible, and often smoothen prices. Meanwhile, the person running the petrol pump gets their own cut.

So, by the time you’re pumping petrol in your vehicle, you’re looking at a very different number — an amalgam of crude prices, hedging, logistics, technology, and a series of profit margins. The final number doesn’t necessarily mirror crude prices.

This is what’s called the “direct channel”. It’s the obvious way in which oil prices affect our economy.

Indirect channel

Zoom out from the pump, though, and there’s a complex mesh of factors that translate crude prices into inflation. These, together, make the “indirect channel”

Everything in our economy, in some way, runs on or is made from oil. When fuel prices go up, as a result, they pull up the prices of everything else in the economy.

From trucks that haul vegetables, to generators that keep factories humming, to all the plastics and fertilizers that are made from petrochemicals — everything becomes more expensive when fuel becomes pricier. Over the following weeks or months, businesses start passing slices of these costs to you. You slowly pay higher prices on groceries, airline tickets, parcel deliveries, and more. So, while fuel costs may be the first thing you notice going up, eventually, the price of everything else follows.

That’s not all. Oil is traded in dollars. As we pay more for oil, the Rupee becomes weaker compared to the dollar. For one, that magnifies every spike in crude prices — importing the same barrel suddenly costs more in Rupees. At the same time, though, the price of everything we import starts going up in tandem.

As all this plays out, people start making bets on the future. If businesses expect oil to stay high, they raise prices pre-emptively. Workers, meanwhile, start demanding higher wages. So what started as a fuel issue morphs into broader economy-wide inflation, not just at the pump.

Put simply: there’s a huge maze of second- and third-order effects that arise out of crude prices, but in a way that isn’t straightforward. These, together, make up the “indirect channel”.

How big is the change?

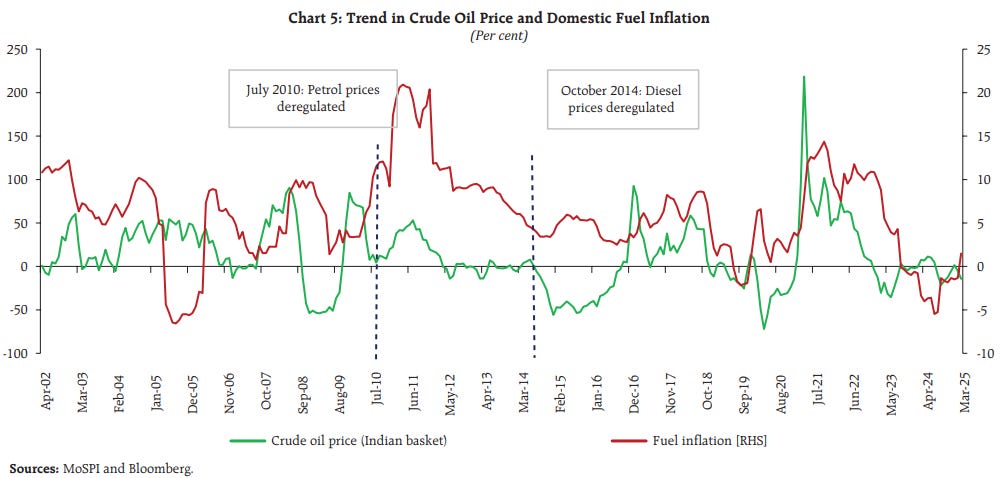

This mish-mash of factors means that the link between crude prices and inflation is weird. Crude prices and inflation rarely march in lockstep. When crude prices increase, the impact on your wallet is extremely messy, with ripples that play out for months.

How, then, should you think about this messiness? Is there a simple way of understanding the link between the two? That’s what the RBI was out to measure.

Its answer can be boiled down to a simple thumb-rule: every time oil prices are up by 10%, India’s inflation climbs by 20 basis points — or 0.2%.

That’s a surprisingly low number. The literature before this suggested that the difference would be more in the range of 0.3-0.6%. Somewhere, somehow, crude prices are getting lost in transmission, with their impact getting blunted in the way.

Why? Part of the answer is simply better monetary policy. The RBI is doing a better job of projecting inflation, communicating its intentions, and setting the right interest rates. But there’s something else at play as well.

Excise duties as insurance?

Before we get there, it’s worth taking a moment to appreciate just how much oil we import.

Around ten years ago, we depended on imports for ~78% of our oil needs. That was high as is. But our dependency has only increased — it’s now more than 88%.

There’s an off-chance this picture may suddenly reverse. From Assam, to Arunachal, to the Andamans, the government has recently announced a wave of recent oil discoveries. This, paired with easier laws around oil extraction could change our import basket. That’s something we’re following closely.

As things stand, though, our dependency is only going up. As per the International Energy Agency, our demand for oil is climbing quickly — by roughly 1.2 million barrels every day. By 2030, we could become the world’s biggest crude oil consumer, as our economy grows.

That essentially makes us global “price takers”. Our economy should be completely at the mercy of whatever global oil markets are doing. And because global oil markets react violently to everything from war, to economic fluctuations, to sanctions all over the world — our own economy should sway dramatically along with all the craziness of the world. But it doesn’t. As economists term it, our economy sees “incomplete pass-through” of global oil prices.

A big reason for this could be the government.

Until recently, the government directly controlled petrol and diesel prices. Back then, the link between global crude oil prices and our own inflation was practically broken. In 2010 and 2014 respectively, however, petrol and diesel prices were deregulated. With that, prices began moving more closely in sync with the rest of the world.

But the government didn’t move away completely. It turned to a more subtle tool — taxes. When we were talking about what you paid at the pump, one thing we didn’t mention was taxes. Those taxes, it seems, are regularly adjusted to counter crude oil prices.

In 2020, when global crude prices crashed during the pandemic, the government raised taxes sharply. It added ₹13 per litre on petrol and ₹16 on diesel. Even though oil itself was cheap, it is the government that reaped most of the benefit, using that money to manage its emergency spending. This is something most people know, and aren’t very happy about.

Once prices surged in 2021, however, the government moved in the opposite direction. In November 2021, excise duties were cut — by ₹5 on petrol, and ₹10 on diesel. Soon afterwards, the Russia–Ukraine war sent oil prices soaring. And so, in May 2022, the government reduced duties once again — by ₹8 on petrol and ₹6 on diesel. Taken together, this meant a total tax cut of ₹13 on petrol (43%) and ₹16 on diesel (60%) within just six months. In short, the government basically rolled back its COVID-era tax increases as successive oil shocks hit the country.

This fundamentally changed how inflation was perceived on the ground. Even though crude prices were rising, pump prices didn’t rise as much. Our oil taxes doubled up as shock absorbers for the economy. Those taxes, in a sense, behaved like an insurance policy against volatility.

An illusion of insulation

If you’ve ever wondered why the price of petrol didn’t skyrocket the last time oil did — you now know why. Crude prices still matter. But if you want to understand inflation, you can’t stop there. You have to follow the chain — through policies, taxes, expectations, and more.

The RBI’s paper leaves us with a warning, however: in an increasingly volatile world, our ability to soften these blows may be reaching its limits. As our dependency on imported oil deepens and global markets get more chaotic, the cracks in this insulation may show. The RBI’s thumb-rule — a 10% oil spike lifts inflation by 0.2% — may not work in the future.

And if that insulation gives way, we may find out just how much we’ve been shielded all along.

Tidbits

After potash, India’s next fertilizer worry? Specialty nutrients — and China’s grip on them.

Nearly 80% of India’s specialty fertilisers — water-soluble nutrients, foliar sprays, polymer-coated urea — are imported from China. And in the past two months, those supplies have slowed dramatically. No official ban, but procedural blocks are piling up, triggering alarm in Delhi.

In response, the Centre is now nudging PSUs, co-operatives, and private players to ramp up domestic production. Talks are underway with firms like IFFCO, Deepak Fertilisers, and Matix.

Source: MintWe saw how different auto makers have different philosophies.

Now, Ola Electric has opposed the auto industry's request to halve the 15% customs duty on traction motors, citing no global supply chain crisis in electric magnets. The company argues that reducing the duty could disadvantage domestic motor manufacturers and disrupt the 'Make in India' initiative.

Source: Business StandardAdding to the pharma updates:

Hyderabad-based Natco Pharma has agreed to acquire a 35.75% stake in South Africa's second-largest drugmaker, Adcock Ingram, for ₹2,000 crore. This strategic move aims to bolster Natco's presence in the high-growth African pharmaceutical market.

Source: Economic TimesIndia will resume issuing tourist visas to Chinese citizens starting July 24, 2025, marking the first time in five years. This move reflects ongoing efforts by both India and China to stabilize their bilateral relations, which deteriorated following a 2020 military clash along their disputed Himalayan border.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

ZERODHA’s The Daily Brief is now my Habit. I never knew until I read today on reinsurance, that it’s so relevant to insurance. I don’t know why none else ever explained this.It really increased my knowledge.

Yes I always wondered why the price of petrol didn’t skyrocket the last time oil did — and, after learning from today’s Daily Brief by ZERODHA’ I do now know why.

Hey, are you planning to do a review of NSDL IPO?