Can JSW craft a slag-to-riches story?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Can JSW Cement crack the big leagues?

The renewables round-up

Can JSW Cement crack the big leagues?

There’s an interesting IPO that’s going to open for bids from 7th August — that of JSW Cement. The company is a small arm of a massive conglomerate, and it’s trying to make its presence felt in an industry which, in the words of its Managing Director, is dominated by players with much greater “aukat”.

This IPO will see the company’s existing investors cash out of nearly ₹2,000 crore. Another ₹1,600 crore will go to the company itself — and might just be the booster shot it needs to break it out of its blues.

This IPO gives us a chance to dive deep into the brutal but fascinating cement industry — one where scale, geography, and timing matter far more than marketing gloss. But it also marks a small but telling moment for this industry, as JSW Cement makes a bid to climb out of the shadows of bigger rivals, and the steel empire that birthed it.

Understanding the cement industry.

India is the world’s second-largest cement producer — although we’re a distant second. Our market share is ~8% of the world. China, the first, makes more than half of the world’s cement. 🤯

But unlike practically every other business we talk about, here, this isn’t an industry where China dominates export markets, under-cutting domestic competitors until they keel over. Its cement exports are fairly nominal. The real contest, in fact, is between the cement arms of giant Indian conglomerates.

That is, at least partly, a function of how cement works. Let’s jump in.

A magical glue

Here’s a simple way to think about cement: if you’d like to build a lot of stuff cheaply, you want to use whatever random sand and rock you can get your hands on. Only, if you tried to do so, it would instantly crumble. Sand and rock simply don’t stick together very well.

But luckily, nature has handed us a little piece of magic: calcium oxide. If you mix calcium oxide with water, it turns into an incredible glue that can hold all that sand and rock together. And one of its cousins — calcium carbonate — is ridiculously abundant all over the world. It is why we can build sky-scrapers out of ordinary earth.

That’s the humble rock you know as “limestone”.

Cement production begins by digging out limestone from giant quarries.

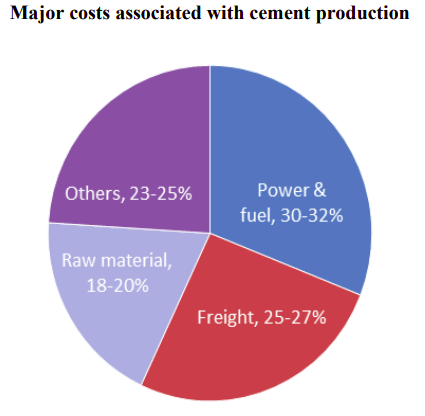

This limestone is mixed with clay, and then heated in huge ovens called “kilns”. This turns it into a hard substance — called “clinker”. This is the very heart of cement making. It’s the hardest part of the process, and costs a lot of energy and money. Your margins all come from how much clinker you use in your cement.

But clinker isn’t cement. It’s still a lumpy, hard substance, which needs some processing to create cement.

Clinker alone is too strong. If you were to add water to powdered clinker, it would set before you could even put it where you want. So, you put in a bunch of other additives — like gypsum, slag, fly-ash, and sometimes limestone itself — to make it behave exactly how you want. And then, you grind it all together in huge mills.

The type and quality of cement produced depends on what you add, and how much you grind it.

How much “clinker” your cement has is measured by its so-called “clinker factor”. In a sense, this defines the “raw power” of your cement. The more clinker you have, the faster and more strongly your cement will set. But making clinker is also carbon-intensive. If you can cut it with other stuff — especially waste products like slag or fly ash — it becomes greener.

JSW Cement uses a lot of slag in making its cement. But we’ll come back to that shortly.

Cement is a geography game

Clinker behaves like small, inert pebbles. It’s stable, and doesn’t react easily with moisture. You can carry huge amounts of clinker over long distances using rail or sea routes, without turning it unusable.

As soon as you turn it into cement, however, it becomes chemically “active”. Even mild humidity can hydrate the cement, and turn it into an unusable cake. Think of it like the difference between transporting coffee beans, and transporting instant coffee.

That’s why cement has a very short travel radius. It needs special trucks, protective packaging, and careful handling. That makes it very expensive to ship. While you can profitably move clinker globally, moving cement beyond a small range kills your margins.

This fact is fundamental to the cement business. Companies can ship clinker globally, but they have to grind it into cement close to wherever it’s used. And so, cement companies place satellite grinding units close to demand centres — like large cities, or highway infrastructure zones — even though their clinker units can be somewhere in the hinterland, near limestone mines.

This creates three dynamics:

One, companies often focus on one part of the value chain. Many just put up grinding units, rather than full-fledged integrated cement plants. You don’t have to build kilns or acquire mining leases to make cement — you can just buy clinker, and set up grinding and packing units. That said, if you don’t control your clinker, you’re vulnerable to price and supply shocks. That’s why, in the long run, “integrated plants” work best.

Two, it makes cement a geographically fragmented industry. India’s cement industry, for instance, is neatly split into four regional strongholds — North, South, East and West.

Three, the cement industry is hotly contested. Each local market is contested hotly by clusters of small, regional players. Each of them faces severe pricing pressure and duplicated costs — and few develop the scale to command premium pricing. Smaller players, with weaker balance sheets, are very vulnerable to input cost swings and freight expenses.

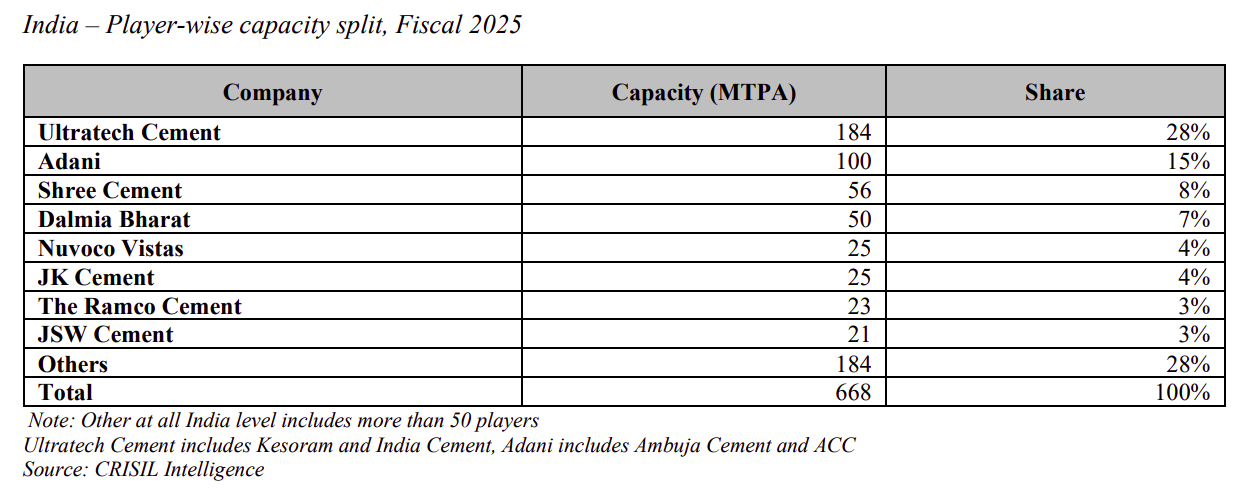

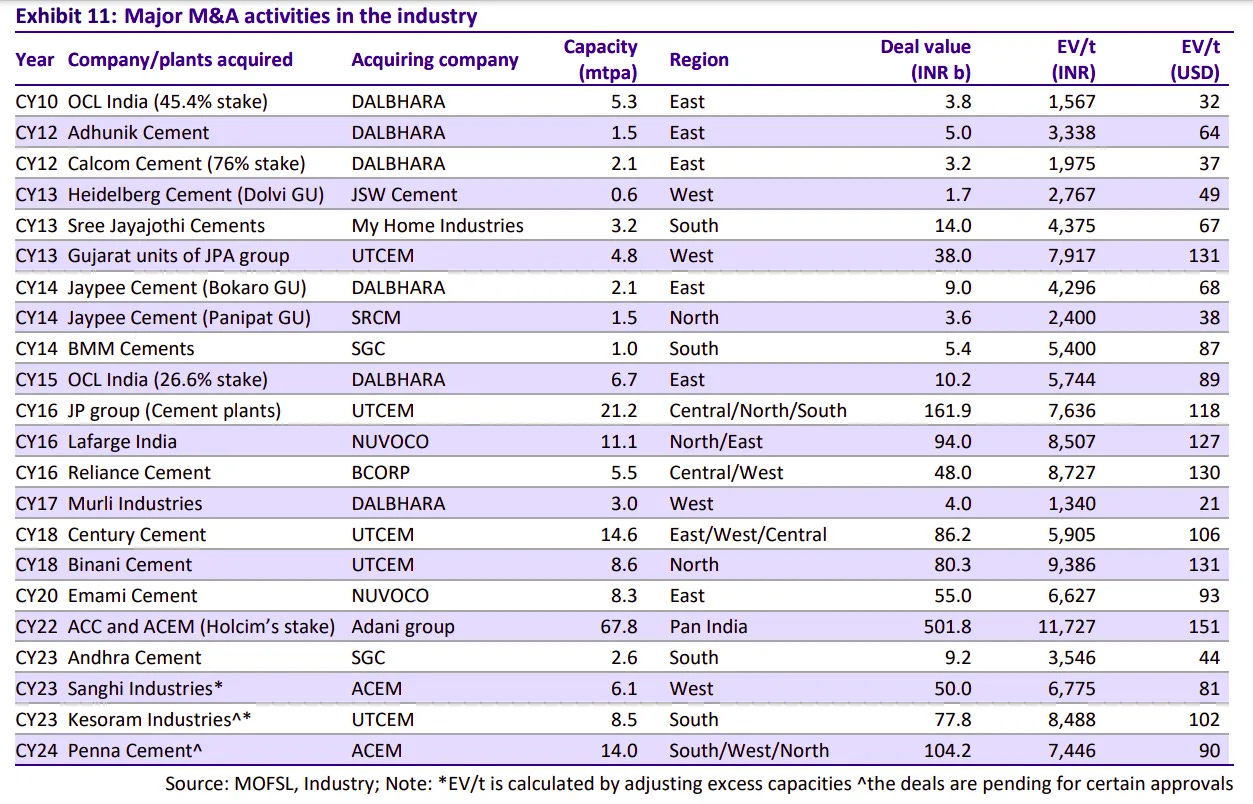

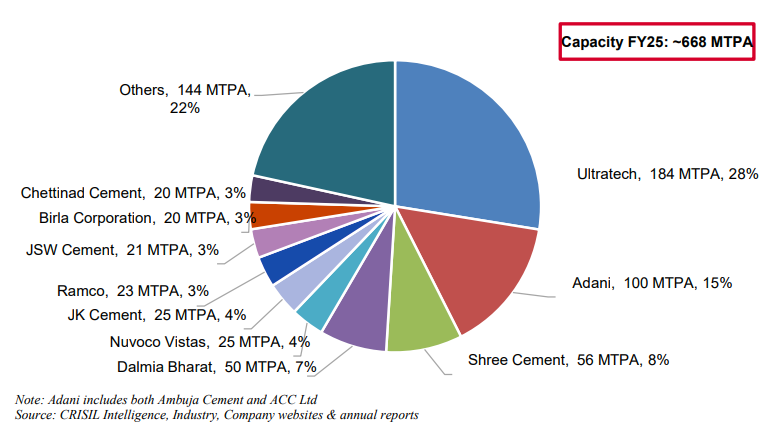

This intense competition has set the Indian cement market on a slow march towards consolidation. As small players struggle — especially during down-cycles — big companies with deep pockets have gone around steadily acquiring these local firms, or edging them out. This has made a company like Ultratech a giant of the industry, as it has gobbled up a series of smaller firms:

But Adani Cement is quickly catching up. In the last few years, it bought out massive players — ACC and Ambuja — in one of the biggest cement deals ever. But others, too, have found their niches. Shree Cement, for instance, has used its strong balance sheet to grow organically in the north and east.

Who do you sell to?

In cement, who you sell to matters almost as much as what you sell.

Broadly, there are two sales channels for the industry: trade (bagged cement sold to individual home builders and small contractors) and non-trade (bulk cement sold to huge infra projects or large real estate players).

Both come with trade-offs.

The trade segment offers better pricing. It fetches ₹30–₹80 more per bag than non-trade sales. If you crack the retail market, it might be sticky and price-insensitive. But it’s also trickier. To make a dent on the trade market, you need deep dealer networks, high working capital, and a lot of trust.

The non-trade channel, when it works, can bag you massive orders. But those players also negotiate harder, and your business becomes lumpy. Once an order is gone, you don’t know if you’ll get another (unless you’re attached to a conglomerate that also does construction).

Whichever way you cut it, though, your margins will always be thin. This is a volume business, and there is no niche pricing here. If your costs are even marginally higher — let’s say due to fuel prices, inefficient logistics, or subscale operations — your company could go under.

The JSW Cement opportunity

If you had access to millions of tonnes of blast furnace slag, what would you do with it?

That was a question JSW Steel was considering. When it made steel, a lot of the dirt and minerals would make slag — clumps of waste rock — which it would otherwise have to throw away. But slag isn’t useless. It’s a natural cement additive, in fact — making your cement stronger and denser.

JSW Group saw an opportunity in its waste. And JSW Cement was born.

The company started as a downstream user of JSW Steel’s slag, setting up grinding units in Maharashtra and Karnataka. Today, JSW Cement makes its core input, clinker, in South India and UAE. That’s turned into actual cement closer to demand centres in the east and west, using slag from JSW Steel plants nearby.

But how good a business is it?

The intensity of competition

JSW is one of the top 10 cement companies in India — with around 20 MTPA of cement capacity. Compared to its peers, though, it’s still a small business. It doesn’t dominate any region, and has little pricing power.

Ultratech, for instance, produces nearly nine times as much cement. Adani, five times as much.

In fact, Parth Jindal, MD of JSW Cement, told this to reporters:

"...if an Ultratech or an Adani or a Dalmia or a Shree wants to acquire anything, they can outmuscle JSW Cement very easily. Right now we don't have the 'aukaat', I would say, to challenge them in any acquisition,"

JSW’s numbers

Here’s a puzzle.

JSW’s revenue has been flat for three years — hovering around the ₹6,000 crore mark. But its profits, through this while, have been sinking. The company made a profit of ₹104 crore in FY23. Two years later, it reported a ₹164 crore loss.

What’s happening?

To be fair, FY 2023 was an unusually strong year. Coal prices were low, volumes high, and a lot of demand came in from the UAE. But since then, fuel and logistics costs have made life much harder, and a lot of money has gone into ramping up one of its subsidiaries.

The company spends a lot of money carrying clinker to its grinding units from distant clinker kilns. But while those costs have climbed, the company hasn’t added much volume, despite adding new capacity.

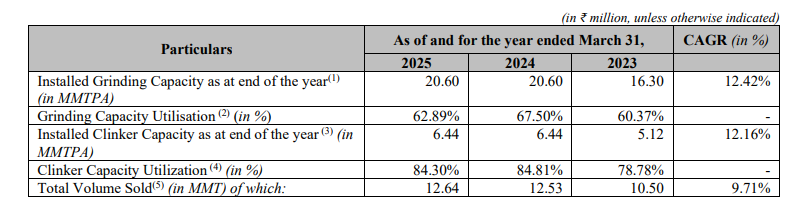

The company is not being able to put a lot of its capacity to use. Its grinding capacity utilisation in FY25 was 62.9%, down from 67.5% in FY24. That is, nearly 37% of its cement-making capacity sat idle. That’s a serious drag for a business where fixed costs are high and volumes mean everything.

Interestingly, through this while, its clinker capacity utilisation held strong at 84.3%. The company, in essence, was running its kilns efficiently — it just wasn’t able to convert all that clinker into sales. There’s probably a buildup of its clinker inventory.

But there’s hope on the horizon. The company has invested heavily in a cement plant in Odisha — under its subsidiary Shiva Cement — which is still ramping up. New units typically take 12–18 months to stabilise.

Paying off debt

The company also carries a fair bit of debt. As of March 2024, its net debt stood at over ₹2,700 crore.

Is that bad? Well, one way of thinking about a company’s debt is to look at the ratio of its net debt to its EBITDA — basically, how many years of operating profit it would take to pay off all its debt, assuming nothing else changes.

For JSW Cement, that number was 2.3x. That’s not dangerously high, but in a business where margins swing quickly with fuel and freight costs, it leaves little room for comfort.

Why IPO now?

All of this should give you a sense of why JSW Cement is making its IPO. It’s trying to use the issue as a lever for its next big leap.

Out of the ₹1,600 crore fresh issue, the company plans to deploy ₹800 crore to fund its upcoming capex — a ₹2,300 crore investment in a greenfield integrated cement plant in Nagaur, Rajasthan. It’ll spend another ₹520 crore to repay or prepay debt.

This new Rajasthan plant could become the jewel in its crown. It’ll give it serious capacity through the supply chain — from clinker production, to cement, to the solar energy it needs to power it all.

It’ll also give the company geographic diversification. JSW Cement currently lacks presence in the north — where prices are high, and demand is strong, despite tighter competition. A plant in Rajasthan could help it serve major markets in NCR, Gujarat, and western UP.

The bottom line

JSW Cement’s IPO makes for an interesting bet.

The company is trying to muscle its way into an unforgiving business where giants already dictate the rules, and where a small patch of bad luck can flip thin margins into losses. Its new plants and debt reduction plan could give it the breathing room it needs to step out of its parent’s shadow and hold its own.

But the road ahead will be long and unforgiving. In this industry, there are no shortcuts. To get ahead, you must survive a slow grind, maintaining cost discipline, and marking out a regional foothold. The market will soon decide if JSW Cement has the strength to make that climb.

The renewables round-up

Last month, India hit a major goal towards a greener future, well ahead of its original 2030 target. 50% of India’s total electricity capacity now comes from non-fossil fuel sources. This is a rare win, which shows just how fast our green transformation is moving.

But this milestone is also the perfect moment to look at what's happening behind the scenes. Because every single step in this transmission is marked by bottlenecks we have to cross.

Here are five major stories that have gone by in just the last couple of months.

ALMM List-II is here

On July 31, the Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (MNRE) published its long-awaited ALMM List-II for solar cells. This is a list of companies with production facilities in India, who together make for 13 GW of solar cell manufacturing capacity.

What does this list do?

See, China dominates the entire solar manufacturing value chain. Their scale and technology gives them massive cost advantages. Most countries simply cannot compete, and end up importing many parts from them. That includes India.

This level of dependency, however, opens us up to a lot of risks. That’s why India is trying to set up manufacturing capabilities within the country — by giving them a source of demand that will be comfortable paying their higher prices.

That’s where ALMM comes in.

The ALMM — or the “Approved List of Models & Manufacturers” (ALMM) — is the government's whitelist of solar manufacturers. Government solar projects, which make up India's largest solar market, can only buy equipment from companies on this list.

Getting on this list isn't easy. Manufacturers had to demonstrate quality standards, production capabilities, and meet various technical requirements. But once the manufacturers make it onto the list, it's essentially a guaranteed market in the government solar pipeline.

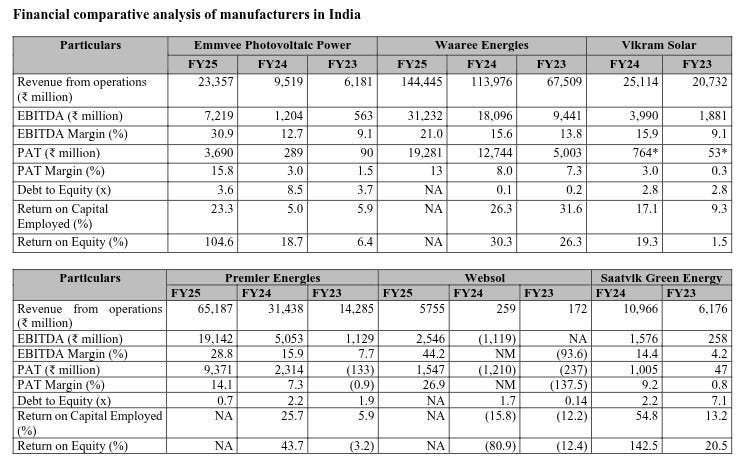

In fact, we recently covered the impact of this policy while talking about Emmvee’s IPO papers. When the ALMM came back in April 2024, after a brief suspension, revenues across the industry shot up instantly. We are talking about increases of nearly 145% year-on-year.

The first ALMM list, in 2019, listed companies that made solar modules. Once it became mandatory for government projects to buy from them, those companies got a lot of business.

That did little to stop imports, though. See, solar modules are basically arrangements of solar cells — the actual units that generate power. Most companies on that original list would import solar cells from China, batch them into modules, and then sell them

And so, the government has now decided to extend ALMM to cells as well — with ALMM List II. Now, even cells that government projects use must come from India. The mandate kicks in on August 31, 2025, although projects that bid before this date are exempt.

With this new mandate, the government is trying to complete India's solar manufacturing story — nudging it to capture the entire value chain. Doing so, however, is a delicate balance. Push too hard and you risk making solar projects more expensive, potentially slowing down deployment. Push too little and you remain import-dependent.

Have we struck the right balance? We’ll know soon enough.

India wants wind turbine makers to go local

Something similar is afoot for wind energy.

On August 1, the MNRE released ALMM-like norms (what we’ll call “ALMM (wind)”) for wind energy. The ALMM (wind) pushes anyone setting up a wind energy project to source key components — blades, towers, generators, gearboxes, and special bearings — exclusively from government-approved vendors.

On paper, India has impressive domestic manufacturing capacity for wind turbines — about 18 GW annually across 14 original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). This includes major listed companies like Suzlon Energy and Inox Wind, and local subsidiaries of global giants like Vestas or GE.

But that’s on paper. Demand is often very lumpy in this industry, and most plants often run at less than 25% capacity. They also source many critical components through imports. Meanwhile, foreign competition, especially from China, is intense. China's Envision Group, for instance, is integrated through the wind manufacturing chain, giving them a huge cost advantage.

The latest rules try to solve for this.

For now, the MNRE has put together the broad policy framework. While putting together stringent norms, it has built in some flexibility for projects already in the pipeline. Companies introducing new turbine models get a grace period — they can use imported components for up to 800 MW worth of projects over two years while they set up local sourcing, but they must report their progress every quarter. It will publish an approved vendor list separately, and set up a technical team for inspections.

But beyond manufacturing, there’s something more interesting that these rules are targeting — data.

Wind turbines generate massive amounts of operational data — wind patterns, performance metrics, grid integration details, and so on. The government doesn't want this information flowing to foreign countries, because of national and cybersecurity concerns. And so, the new norms mandate that all wind turbine operational data must be stored within India. Real-time data transfers abroad are banned, and companies must set up operational control centers and R&D facilities in India within one year.

Can domestic suppliers really scale up successfully under these norms? If yes, India could not only build its own manufacturing capacity, but could potentially emerge as a major exporter. If not, the aggressive localization push might slow down India’s already suffering wind energy ecosystem.

Renewables gets a boost through VGF

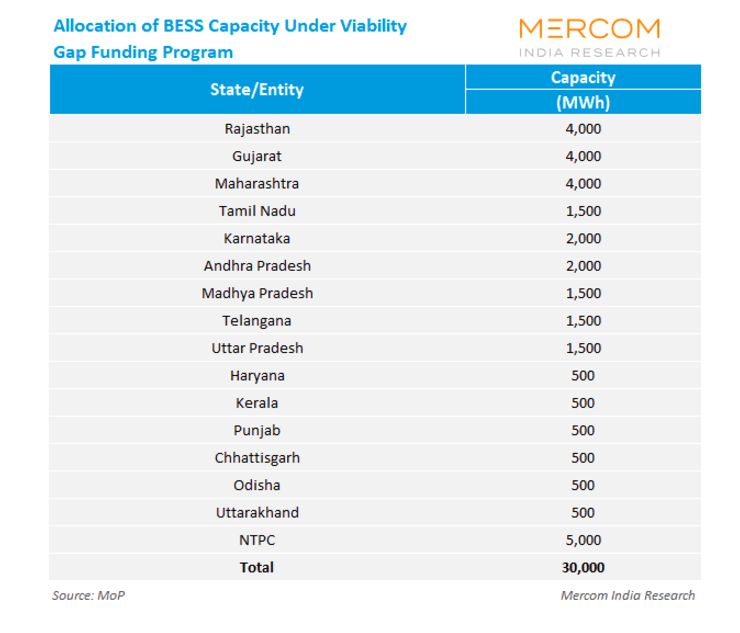

This June, the central government approved a ₹5,400 crores “Viability Gap Funding” (VGF) package to support 30 GWh of battery energy storage systems, across 15 states and NTPC.

The concept behind VGF is straightforward: some infrastructure projects make perfect sense for the country but are terrible for private companies' balance sheets. Think of a new metro line for example. It could be exactly what a city needs, but the private company building it might never recover its investment. VGF bridges this gap, providing grants that cover part of the upfront cost for private companies.

This mechanism, naturally, is perfect for many renewables projects.

Consider storage. Battery storage systems cost a fortune upfront — you're buying thousands of lithium-ion batteries, plus all the cooling and safety equipment to house them. But they make money slowly. They buy electricity when it's cheap and sell when it's expensive, but that price difference is often just a few rupees per unit.

That makes it exactly the type of project that could benefit from VGF.

Energy storage in India received its first dedicated VGF support in 2023, targeting 13.2 GWh of battery energy storage system (BESS) projects. The latest round doubles the existing VGF support to over 43 GWh total.

There are other projects that have gotten VGFs too. In June 2024, for instance, the Cabinet approved ₹7,453 crore in VGF specifically for offshore wind energy projects — one of India's first serious attempts at harvesting wind power from the ocean.

The appeal of offshore wind is simple: ocean winds are stronger and more consistent than onshore winds. But there's a reason India hasn't done this before — offshore wind is terribly expensive. You're building wind turbines in the middle of the ocean. You need to take turbine blades longer than football fields, and towers taller than 40-story buildings into deep waters. You need specialized ships, underwater cables, and maintenance teams that can work in harsh conditions. The upfront costs are roughly 2-3 times higher than onshore wind projects. All these challenges translate directly into financial risk.

That's exactly why VGF makes sense here.

VGF support is essentially the government's way of subsidizing the learning curve of doing hard things. The idea is that once developers figure out how to make this work, future projects should become commercially viable without government support.

A renewable energy subsidy just expired

On June 30, India ended the 100% waiver on inter-state transmission system (ISTS) charges.

Think of ISTS charges as toll fees for electricity. When a solar farm in Rajasthan wants to sell power to factories in Maharashtra, that electricity needs to travel through transmission lines across state borders. ISTS charges are what developers pay to use this interstate highway. These charges typically range between ₹0.50 to ₹1.50 per unit of electricity, depending on distance and route.

For renewable energy projects, those charges were often the difference between being profitable and losing money. That’s why the government introduced a 100% ISTS waiver for renewable projects in 2016, hoping to make renewable energy competitive with coal power. That small reduction helped solar and wind projects win more auctions against conventional power.

The scheme was originally supposed to end in 2019, but the government kept extending it as renewable energy capacity grew.

But that’s ending now, for one reason: the waiver worked too well.

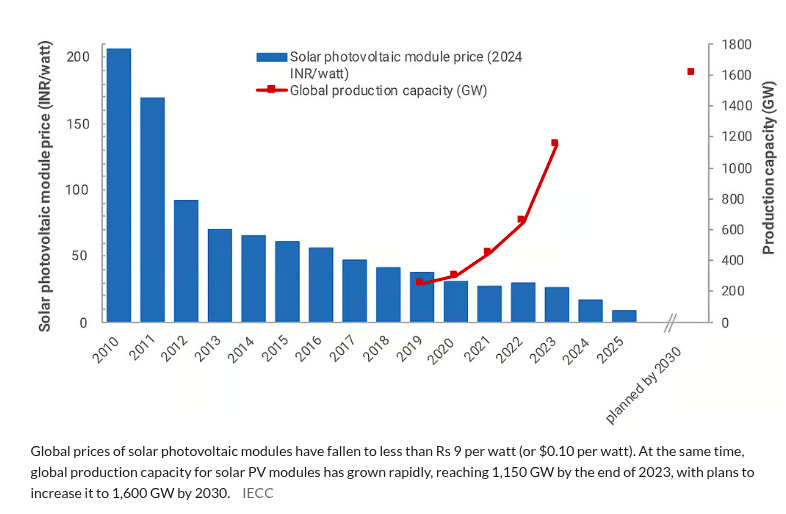

Renewable energy costs have dropped dramatically since 2016. With renewables now cost-competitive with coal power even without subsidies, the government decided it was time to phase out the support.

But the end isn't abrupt. The government has built in a phase-down schedule where the waivers reduce over the years, finally ending after June 2028

The ISTS waiver phase-out signals the government's confidence that renewables can now compete on their own merit and it’s time to focus on other aspects of the renewable energy boom, like storage and grid flexibility. For instance, the government has extended 100% ISTS waivers for battery storage and pumped hydro projects until 2028.

India's grid crisis gets worse

India's stranded renewable power capacity more than doubled in just nine months, going from 20 GW in October to over 50 GW by June.

Companies like JSW, NTPC, Adani Green, and Renew Energy have billions of dollars worth of projects — nearly a quarter of India's entire current renewable capacity — which are ready to generate power, only, they can't reach buyers. Not because there's no demand, but because the grid infrastructure to deliver that power simply doesn't exist.

The grid is basically a massive network of power lines, substations, and transformers that help carry electricity from solar and wind farms in sun-drenched states like Rajasthan and Gujarat to other parts of the country.

And we don’t have nearly enough of this critical infrastructure.

India plans to connect 230 GW of renewable projects through interstate transmission lines, but only 20% are complete. Meanwhile, legal disputes over land and environmental permissions are keeping projects stuck in court for years.

This is one of those hard but under-rated problems that we’ll have to solve if we want any hope of making a green transition.

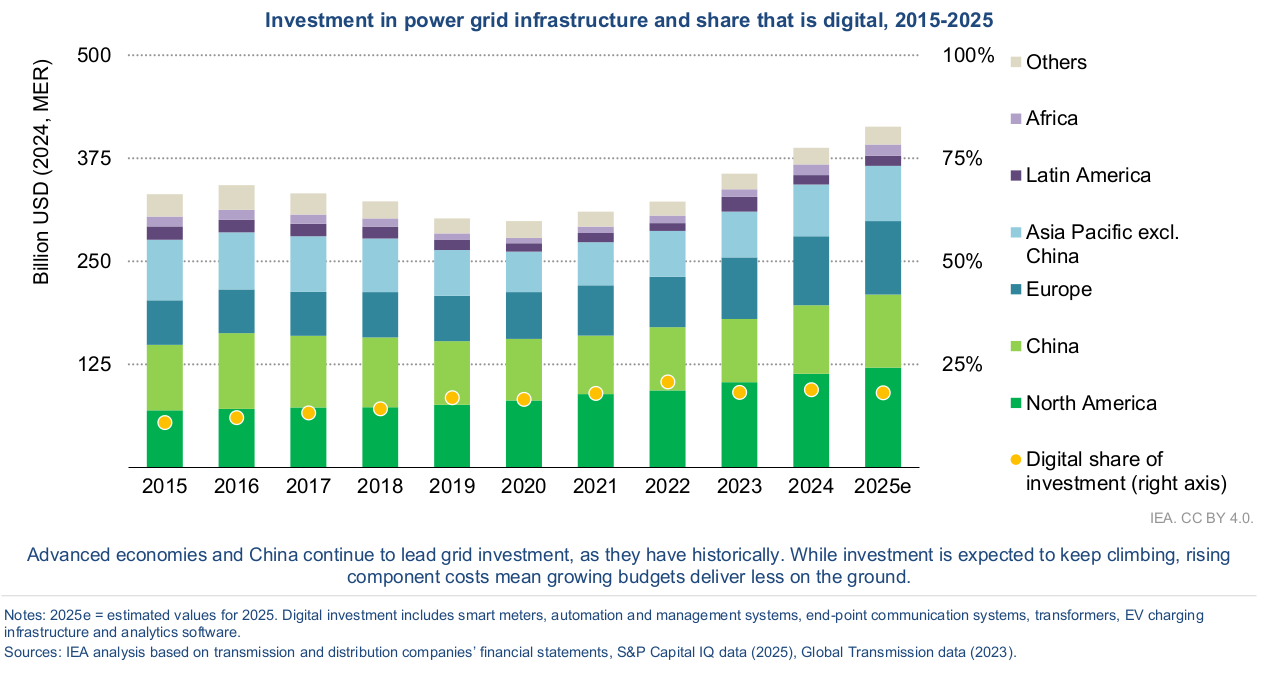

This isn’t just an India problem. As we covered earlier, back in 2016, for every dollar spent on building new power plants, we invested 60 cents in the grid. Today, that has dropped to less than 40 cents.

Tidbits

Amid the backdrop of stricter steel import curbs:

JSW Steel and Japan’s JFE Steel have announced a ₹5,845 crore investment to expand grain-oriented electrical steel capacity at Vijayanagar (Karnataka) and Nashik (Maharashtra). The combined capacity will reach 350,000 TPA by FY28, targeting India’s growing green energy and transformer market while reducing import dependence.

Source: Business StandardIndia’s electric scooter race saw a big boost for Ather Energy in Q1 FY26.

The company reported a net loss of ₹178 crore, slightly lower than last year’s ₹183 crore. But operating revenue surged 79% YoY to ₹645 crore, driven by volumes nearly doubling. EBITDA margin jumped to 16%, a dramatic swing from -33% in Q1 FY25.

Source: Money ControlIs there a light at the end of the tunnel for IndusInd Bank?

IndusInd Bank’s stock jumped over 5% on August 5 after naming Rajiv Anand—former Deputy Managing Director of Axis Bank—as its new Chief Executive, raising optimism about a leadership-led turnaround. Anand’s appointment, approved by the RBI for a three-year term starting August 25, aims to restore confidence following earlier accounting issues.

Source: ReutersIndia’s appellate tribunal NCLAT has granted interim relief to Vedanta by staying the NCLT’s March order that blocked its demerger proposal, conditional on a ₹1,245 crore bank guarantee in favour of SEPCO. The move allows Vedanta to proceed with its business restructuring plan while the case is heard again on August 4.

Source: Mint

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Prerana

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Very nice Daily brief. Now it is becoming habit for me read it on daily basis. Learning many things, thanks to this daily briefing.

India’s share in cement production is 11.25% I think based on the chart that you have added. You guys have taken the CY18 production market share I believe.